Published October 31, 2007 at 1:38 p.m.

Paul Cillo is offering chocolate kisses to anyone who can answer a few basic questions about the state budget process. "When does Vermont's fiscal year begin and end?" he asks from the head of a large conference table in the Capitol Plaza Hotel in Montpelier.

"July 1 and June 30," shouts one of the 30 or so people in attendance. Cillo tosses a chunk of chocolate across the table.

"And where does the budget originate?" he asks the audience of housing experts, child-welfare advocates and other professionals in the public and nonprofit sectors, who are convened for a daylong conference titled "Choices for Vermont: Creating a Better Future for All Our Children."

"The governor's office," someone else bellows. Another piece of candy sails across the room.

The questions get progressively harder. "What's the single largest source of funding for state government?" The room falls quiet for a moment until someone guesses correctly: "the federal government." Cillo launches another foil-wrapped sweet.

"And when is the first opportunity for the public to weigh in on the budget process?" There's a long pause before someone explains that it's only after the governor presents his proposed budget to the legislature in January. But even that answer evokes several caveats and "yeah, buts . . ."

The point of Cillo's exercise isn't to expose the collective ignorance of the people seated around the table, many of whom spend much of the year lobbying the Vermont Legislature. Cillo, who is executive director of Vermont's newest public-policy think tank, Public Assets Institute, is highlighting a fundamental flaw in the democratic process: Namely, that it's very hard for even the most informed and well-intentioned Vermonters to access vital information about how public money is gathered and spent.

In fact, many seemingly simple questions about state finances cannot be answered quickly or easily, even by the experts. He tells a story about Steve Klein, director of the nonpartisan Joint Fiscal Office. JFO staffers are the legislature's official number crunchers on all budget and revenue matters. Recently, Klein got a phone call from a reporter at a national money magazine, who asked: What was Vermont's budget growth over last year? The reporter got angry when Klein couldn't give him a brief, sound-bite answer. But, as Cillo explains, Klein wasn't being cagey or evasive. The fact is, there's not a single, widely agreed-upon definition of what constitutes "budget growth."

Or, consider the fact that Uncle Sam is the single largest contributor to Vermont's coffers, funding about 32 percent of all state services annually, according to Cillo. One would assume there's a spreadsheet or web page out there that accounts, line by line, where all that money comes from and where it goes. At the state level, that document is called a "sources and uses" sheet. Surprisingly, no such document exists for federal money flowing into Vermont. Is the data out there and available? Yes, Cillo says. But is it readily accessible to the public in a simple, standardized and easy-to-use format? Nope.

The problem, Cillo asserts, isn't that government officials are lazy, incompetent or conspiring in smoky boardrooms to keep Vermonters in the dark. The reality, he says, is that there's neither a mindset nor a process in state government that invites public participation in the budget-making process. "The question I would ask is, is there another way?"

Cillo believes there is. He founded Public Assets Institute in 2003 in an effort to provide lawmakers, journalists, public advocates and average citizens with "sound, timely and understandable analyses" of state budget and revenue matters. Though PAI describes itself as an independent, nonpartisan and nonprofit group whose mission is to keep the public informed about how government spends money, its values seem decidedly small "p" progressive. Its goal is to "promote public policies that improve the wellbeing of all citizens, especially the most vulnerable." The bulk of its funding to date has come from the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

PAI has been around for four years, but has only recently begun to raise its public profile with conferences, reports and regular email newsletters on various fiscal and budget policy topics. Until last year, the "Institute" was just a part-time, one-person operation. But Cillo is fast becoming the "go-to" guy for independent tax and budget analyses. This is especially true whenever Governor Jim Douglas makes claims about Vermont's tax burden or its unfavorable business climate that go unchallenged by his political opponents or the press.

"I don't want to say that the other side is lying, but it is all about telling the truth," notes Hal Cohen, executive director of the Central Vermont Community Action Council, an antipoverty agency that serves Orange, Lamoille and Washington counties. "One of the things we realize is that fiscal analysis has as much to do with what questions you ask as it has to do with the numbers themselves."

CVCAC is one of several nonprofit groups in Vermont that have begun turning to PAI to ask the tough questions, even when those questions are not politically convenient. For example, several years ago Cillo discovered a little-known provision in state law that required the transfer of money from the general fund to the education fund to grow at the same rate as the general fund itself. For instance, if the general fund grew at a rate of 6 percent, the transfer of money to the education fund was also supposed to grow at 6 percent.

However, when Cillo examined the numbers, he found that the transfer was only growing at a rate of 4 percent, leaving a $25 million shortfall in the education fund. "That year, the governor was campaigning on affordability and lowering property taxes. Meanwhile, he signs a bill that shortchanges the education fund and raises property taxes," Cillo asserts. "Who's thinking about that and pointing that out? Nobody."

Cillo's goal wasn't to embarrass the governor; in fact, the education fund shortfall was just as awkward for Democratic lawmakers, who had to make up that shortfall in the general fund as well. Instead, PAI is positioning itself as a truly independent fiscal watchdog, whose work is especially valuable for small nonprofit groups that don't have the time, money or expertise to do their own heavy lifting.

"We spend $4 billion a year, and those choices really express our state's priorities," Cillo says. "Our challenge is, how do you sift through this ton of information and make sense of it?"

For most Vermonters, the thought of sifting through reams of state budget figures is about as desirable as a root canal, and much more costly. Few Vermonters have either the time or know-how to make sense of all that raw data. But for nonprofit organizations that depend upon state funding for their existence, understanding how money gets allocated can mean the difference between serving their clients and closing their doors.

"In my world, in the world of human services, we're not always good with numbers and understanding budgets," admits Rep. Ann Pugh (D-South Burlington), who's also a senior lecturer in the Department of Social Work at the University of Vermont. "The work that Paul is doing is very helpful . . . So much of what we talk about [as lawmakers] can get lost in jargon or in the assumption that everyone knows the minutiae."

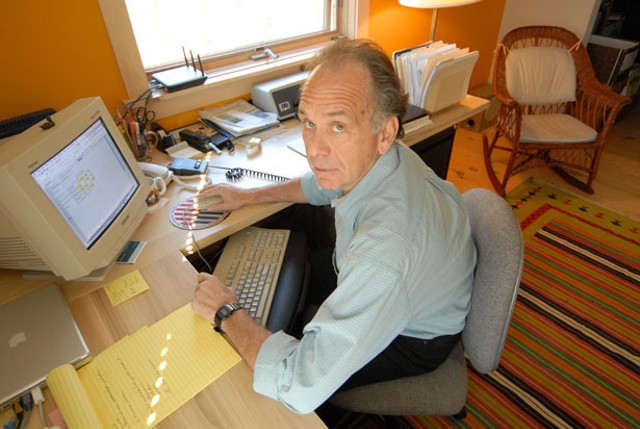

Much of Cillo's expertise in the "minutiae" of state fiscal matters comes from personal experience - a Castleton native, he spent 10 years in the Vermont House of Representatives; four years on the House Ways and Means Committee and another four as majority leader. In the mid-1990s, Cillo was the chief architect of Act 60, the law that restructured how public education is funded in Vermont. He lost his bid for reelection in 1998.

One of Cillo's complaints about his time in the legislature is that he never really got an opportunity to do serious, long-range planning. "It was always about putting out fires," he says. "One of the things I could see from inside the building was that it's very easy for the legislature to get off on some tangent that's completely disconnected from the reality of Vermonters."

Part of the problem, Cillo says, is that no one - not lawmakers, not the governor, not even public advocates or the press - have the time to step back and look at the big picture. Each state agency and department worries about its own budget; each publicly funded organization and program tries to ensure that its line item doesn't get axed.

For his part, Cillo is trying to step back and study that sprawling landscape. For instance, he analyzed 15 years of budget trends in Vermont and found that funding for education has been steadily declining, spending on security and public safety has been steadily rising, and the state is increasingly dependent upon federal money and one-time special funds to make ends meet.

Cillo is also interested in challenging certain prevailing views that, in his estimation, have no basis in fact. For instance, when the governor came out last year and said that Vermonters are saddled with one of the heaviest tax burdens in the nation, Cillo and Burlington economist Doug Hoffer put out a report showing that, quite the contrary, Vermonters have a relatively progressive tax structure. Those findings were confirmed by a recent report from the Joint Fiscal Office.

"Is Paul saying that property taxes in Vermont are OK? No, he's not saying that at all," notes Senator Doug Racine (D-Chittenden). "We can debate how much we should be taxing ourselves. But let's start with the facts, and not a bias that's based on inaccurate information."

PAI is still a very small outfit, with only three full-time staffers operating out of a small office on Elm Street in Montpelier; much of its work is done by outside consultants, including Hoffer and independent analyst Deb Brighton. But several weeks ago, PAI hired Jack Hoffman as a senior policy analyst. Hoffman is a 25-year veteran reporter who spent two decades covering state government for the Times Argus and Rutland Herald. For the last five years, he headed the now-defunct Vermont Broadband Council.

PAI hired Hoffman not only because of his years of investigative reporting experience, ferreting out hard-to-find information on tax and budget issues. It also reflects an effort to correct a troubling trend in journalism; namely, that fewer and fewer newspapers, in Vermont and nationally, are devoting resources to covering state government. To wit: The Burlington Free Press, Vermont's largest newspaper, no longer maintains a statehouse bureau.

Hoffman's primary job right now is to get PAI's "Budget Transparency Project" up and running. As he explains it, most people assume that the purpose of open government is just to keep elected officials honest. But as he points out, open government is also an opportunity for leaders to tap the knowledge and experience of ordinary citizens. This is especially true for Vermont's citizen legislature, where new lawmakers come into the process with varying degrees of expertise and education on financial matters.

"You and the rest of the public are not meant to be just spectators and passively accept information about what's going on," Hoffman says. "You have to get it in a way that allows you to participate and affect what happens."

PAI's Budget Transparency Project has three components, Hoffman explains. First, its goal is to educate the public about the budget process itself and put out a consumer guide that explains how average citizens can get involved. Second, the project will collect, compile and maintain budget data in a format that allows everyone, "both neophytes and veterans," to do their own research.

Finally, the project will try to reform and standardize the budget process, so everyone involved in policy debates is "starting from the same page." For example, what does it mean when a state agency or program is "level funded," Hoffman asks. Does that mean it's allocated the same amount of money as it got last year? Or, does it get the amount of money it needs to maintain the same level of services? "If we can't even agree on those facts," Hoffman says, "it's hopeless for us to try to have a meaningful policy discussion."

*******************

Public-policy think tanks are few and far between in Vermont. For the last 14 years, the Ethan Allen Institute in Concord has commanded the conservative end of the spectrum, upholding such values as individual liberty, private property, competitive free enterprise and limited and frugal government. Its president, John McClaughry, consistently champions a fiscally conservative viewpoint in frequent editorials and op-ed pieces.

McClaughry expects that the public-policy positions of Cillo, Hoffman and PAI will run contrary to most everything he believes in. He calls them strident advocates for big government and higher taxes. "Has there ever been a tax that Paul Cillo and Jack Hoffman thought ought to be reduced?" McClaughry asks.

And, he chuckles at the notion that PAI is now championing the cause of greater budget transparency. As he points out, many of the conservative groups he supports or belongs to, including the State Policy Network and Grover Norquist's Americans for Tax Reform, have long advocated that very same goal. "Eliminate waste, fraud and abuse, as the Republicans always say."

That said, McClaughry welcomes PAI's presence on the political scene. "That's what democracy is all about, the clash of ideas," he says. "And PAI will certainly accentuate that clash of ideas." In fact, McClaughry says he respects much of Cillo and Hoffman's past work, even when they've been on opposite sides of the debate from him.

"I will say that Jack was always the first place you went to get information about state spending when he was a reporter, and that can be dreary stuff," he says. "I'll read his stuff, but don't read anything he writes about supply-side economics, because he's dead wrong!"

Some folks in the legislature say they're glad to finally see a political counterweight to the Ethan Allen Institute's free-market bias. "It's good to have somebody besides John McClaughry analyzing things, because John McClaughry doesn't analyze," says Sen. Racine. "He's just a mouthpiece for the Heritage Foundation."

But others put Public Assets Institute in a different category than the Ethan Allen Institute, in large part because Cillo is doing his own research and analysis. "Public Assets Institute has not, to my knowledge, put out reports that are a regurgitation of material that's put out nationally," Pugh suggests. "They're doing original, independent research, and that's a really important service to Vermont."

Representative Michael Obuchowski, who chairs the House Ways and Means Commit-tee and co-chairs the Joint Fiscal Committee, says that PAI is performing an invaluable service for lawmakers. He says that while the JFO does a "marvelous job" on complex budget issues, he admits the office has a small staff that cannot do everything it's asked to do. Increasingly, lawmakers have to rely on information provided to them by interest groups, lobbyists and ordinary citizens.

"I've been in meetings with Paul when he's been asking the hard questions," he says. "And, he's getting the answers . . . I think he calls 'em as he sees 'em."

It doesn't hurt that Cillo, 54, is "one smart dude," as Obuchowski puts it. Or, that he comes across more like a college professor than a politician - genial and patient, with a tendency to explain his position rather than argue it. Interestingly, Cillo's 1975 degree from UVM is in philosophy, not math or economics; in his twenties, he discovered he had a knack for policy analysis while working for the Department of Corrections. Fellow lawmakers who served with Cillo in the 1990s describe him as thoughtful and bright, with a skill at making people feel at ease.

Although he describes his organization as "nonpartisan," Cillo clearly has a point of view; namely, that government still has a role in advancing the public good.

John Fairbanks is the public affairs manager at the Vermont Housing Finance Agency, a nonprofit agency that finances and promotes affordable housing for low- and moderate-income Vermonters. He says the state has long needed the independent budget analysis that PAI is doing.

"I'm one of those people who believes that the role of the public sector has been unfairly vilified," Fairbanks says. "You say 'big government program' and some people react with an almost Pavlovian response.

"If you think about it, the federal government has sort of been a deadbeat dad," Fairbanks continues. "It's essentially walked away from funding necessary public services and dumped them on the states."

PAI intends to make policy recommendations and suggest reforms to the budget-making process. But ultimately, Cillo doesn't see PAI as advocating one particular political viewpoint so much as getting inside the numbers to see where they're leading us. Only then, he says, can Vermonters have a meaningful debate about the direction they want to go.

"There's an almost fetishistic reluctance to discuss revenue issues," Cillo says. "It's irrational. The basic idea of being unwilling to think about the state we want because we're unwilling to talk about what it costs."

More By This Author

Speaking of Politics,

-

Bernie Sanders Sits Down With 'Seven Days' to Talk About Aging Vermont

Apr 3, 2024 -

Al Franken Blends Satire and Political Commentary at Flynn Show

Sep 19, 2022 -

Candidates for Governor Display Stark Differences at Tunbridge Fair Debate

Sep 16, 2022 -

Weinberger Removes Racial Equity Director From Oversight of Policing Study

Mar 16, 2021 -

Sirotkin Criticizes Grant Program — to a Larger Audience Than He Intended

Feb 24, 2021 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.