Published August 5, 2009 at 6:00 a.m.

When Thomas Middleton enlisted in the Army Reserve in 1985, he never actually expected to go to war. Then a 17-year-old high school student in West Chazy, N.Y., Middleton saw the reserves as an exciting opportunity, but also as a mere “vestigial organ” of the U.S. military, he says. In an age when mutual assured destruction was “the theory of the day,” he assumed a conventional ground war was unlikely in his lifetime.

Eventually, Middleton found his true calling: saving lives, first as a volunteer firefighter, then as a nurse and career firefighter. After being hired by the Burlington Fire Department in 1992, he asked a local recruiter to find him a nearby National Guard unit that needed medics. He still wanted to serve his country in a military capacity, but he wanted that service to matter.

Years later, Middleton’s service did matter, critically, to the scores of fellow soldiers he rescued on the battlefield. In 2004 and 2005, he was deployed as a combat medic in Ramadi, Iraq, as part of Task Force Saber, where he saw some of the fiercest fighting of the war.

Unlike his fellow Vermont National Guardsmen, Middleton traveled between platoons, filling in for missing medics. In the process, both his medical training and his faith were put to the test, as he tried to balance the seemingly conflicting values of caregiver, killer and Catholic. As he explains, when you’re one of four infantrymen in a patrolling Humvee, there’s no room for the physician’s credo of “First, do no harm.”

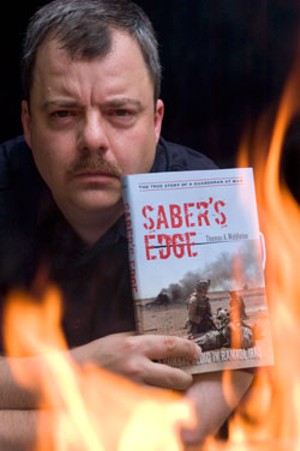

Earlier this summer, Middleton published Saber’s Edge: A Combat Medic in Ramadi, Iraq, a firsthand account of his war experiences. Adapted from diary entries and emails to family and friends, the book explores the 24/7 stresses of modern-day warfare, fought against an often invisible and intractable enemy. It also explores the moral dilemmas that come with inflicting wounds and healing them — and knowing you may be performing both actions on the same person.

Middleton, 41, is now an assistant fire marshal and public information officer with the Burlington Fire Department. He sat down with Seven Days to discuss his book and his experiences during his year in combat.

SEVEN DAYS: Why did you write this book? TOM MIDDLETON: Originally, it was a catharsis. I got back from the war, and the war was on my mind all the time.

SD: In a good way or bad way? TM: Not in a good way. I was physically present back in the United States with my family, but Ramadi was always present in the front of my mind. I talked about it with my wife — she’s an ER nurse by training — and she got tired of listening to my war stories. It was her idea, actually ... So I pulled out the laptop and in the first night wrote the first five chapters.

SD: Did your friends, family and coworkers understand what you were going through? TM: No, not much at all. Folks tried. They were very sympathetic to the plight of the veteran and very supportive of our troops. But for those who’ve never served or been to war, it’s very difficult for them to imagine the kinds of things we talk about. So most combat veterans don’t talk about it a whole lot, and when we do, it’s among ourselves. And that’s part of the reason I ultimately decided to publish it. After a year of [the book] sitting on my shelf, waiting for my grandkids to be old enough to read it someday, I decided there might be some healing that could be accomplished for people who don’t understand what their friend, their neighbor or their family member went through.

SD: In previous wars, the lines between medic and combatant were more clearly drawn. TM: Not so much in this war, and even less so for me than for some other folks.

SD: Why is that? TM: If we start with an examination of the Geneva Conventions, it starts with physicians and chaplains identified with crosses and medics with red crosses. Those folks are stepping forward and identifying themselves as noncombatants, and, ethically, the enemy is supposed to respect that and not shoot them. And if they’re captured, they’re supposed to be able to practice their medicine or extend their ministry to their troops. That’s the concept.

In reality, we’re not facing a uniformed army that honors the tenets of the Geneva Conventions. We’re facing an enemy that wears civilian clothes, melts into the civilian populace and triggers IEDs with cellphones. These folks don’t respect the Geneva Conventions. If we wore the red crosses, we’d be claiming our status as noncombatants ... but I never did that, because it would be unethical. I would be claiming to be a noncombatant when I was a combatant ... Also, I didn’t want to be targeted. Taking out a medic would demoralize the rest of the fighting unit and make them less willing to take chances.

SD: Did you ever treat wounds that you inflicted? TM: I think so. I never knew for sure. There were a lot of times when I was part of the engagement and it was difficult to discern who fired which shot for what injury. It’s pretty likely that I did. The only time it struck me was when I saw an Iraqi police officer who turned on us during an ambush ... He was laying there, deceased, in an Iraqi police uniform. That was very unsettling at first, to realize we’d killed a police officer. But he was a traitor who used the weapons issued to him against us ... What it boils down to is, it’s still a human being. And while that human being poses a threat, it’s justifiable to defend yourself, your patients and your brothers standing next to you and engage in the mission ... But when he’s surrendered and has medical needs, it’s our moral responsibility to provide care to them.

SD: What was that like? TM: I won’t lie to you. I won’t pretend that I cared whether an enemy combatant suffered or not. After a while, I lost compassion for the enemy combatants. I treated them, and I treated them with dignity and respect because it was the right thing to do, not because I cared about them.

SD: Did it change the way you felt about and acted toward civilians? TM: Yes. We just couldn’t trust civilians. We couldn’t trust anybody. I learned through experience that the vast majority of them were indifferent to our presence and just wanted to go about their day, go to school, take care of their children and so forth. But we could never tell who was an insurgent and who was just a bystander. So we had to just watch their actions and try to figure it out.

SD: As a firefighter, you need to put your own safety first so you don’t become a burden to fellow rescuers. But as a combat medic, you often put yourself into dangerous situations, such as kicking in doors. Was that difficult? TM: No. It was easy to make that decision. The creed of the noncommissioned officer is,“The mission, the men and then me.” In the military, our troops are expendable. The mission comes first. In combat, there are losses. They’re unpleasant and we try to avoid taking casualties, but we realize the mission must go on. In the fire department, we take just the opposite approach. We have a mantra these days in the American Fire Service: “Everybody goes home.” ... Given the volume and frequency and intensity of the combat operations I was involved in, I came to accept that I was likely going to die there, but I was going to do as much good as I could before that day came.

SD: As someone with strong religious beliefs, what was the hardest thing for you to reconcile about the war? TM: From the time I first joined the military at 17, I could accept the distant concept of killing in a just war, in self-defense or the defense of others. But it was just a concept. It was abstract. Later on when I went into Iraq, the first time I had to fire and take someone out, I didn’t feel anything initially. It was very simple: I saw a threat, I engaged the threat, and the threat went away. Whether he was killed, wounded or scared, I’ll never know. I didn’t check. He was too far away. I didn’t feel any remorse. I did what I was supposed to do.

SD: When did that change? TM: When I read on the Internet that Pope John Paul II had some deep reservations about whether this war was moral or not — I’m Roman Catholic. On matters of faith and morality, the pope is considered infallible. He speaks in God’s voice ... So when I heard that, it was very upsetting. It caused me to reevaluate in my mind about what we were doing there, how we were doing it, and whether we should or shouldn’t have been there. All sorts of questions came to the forefront.

SD: You eventually went to your chaplain, who showed you some writings from the pope following his meeting with President Bush. TM: Basically, it became OK because ... the decision to go to war is made by your elected leaders and your government, and the moral responsibility to go to war rests with those leaders. Whether it was right, wrong or indifferent ... our elected officials, our nation, made that decision. I didn’t make the decision. I’m a soldier. I do what I’m ordered to do, unless it’s a totally immoral or illegal order. So that part of it fell away. Having now taken over Iraq from their Iraqi government, we are encumbered with a moral responsibility to set things right for the Iraqi people.

SD: How did you change as a person by going to war? TM: I’ve got an edge to me now that I never used to have. I used to be pretty happy-go-lucky the majority of the time. It took an awful lot to get me upset about anything. As a byproduct of having to ... be hypervigilant every minute of every day, with threats coming from every direction, I became quicker to anger. Although I wasn’t angry all the time, I harbored a lot of anger and resentment for the way we were treated, resentment toward the Iraqi people. I felt that we were there to help them and they weren’t appreciating it and stepping up and taking ownership of their own lands and cities ... I came back angry, quick-tempered and constantly thinking about the war. But that’s faded over time.

SD: The book helped? TM: It did. It helped initially get all that stuff out of my head. At some point, I’ll put all this behind me and won’t be writing about the war anymore. I’ll write something funny about the fire department or nursing.

Want to learn more?

Thomas Middleton discusses Saber’s Edge on Thursday, August 13, at Briggs Carriage Bookstore in Brandon, 7 p.m. Free.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Sugarbush Owner, Former Merrill Lynch Exec Win Smith Writes Book

Jan 8, 2014 -

Vermont College of Fine Arts to Welcome Best-Selling Novelist Julianna Baggott

Dec 18, 2013 -

Meet the Authors

Dec 19, 2012 -

As Goes Japan...

Jan 11, 2012 -

Rootsy Reading

Dec 21, 2011 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.