Published May 23, 2007 at 11:33 a.m.

Memoirs are a tricky business these days. While they've displaced fiction in terms of sales, the market for true stories is so glutted that it's no longer sufficient to have an eccentric family or a checkered past. On the one hand, we're seeing fewer sensationalist, "I-was-a-teenage-klepto-alkie" memoirs and more thoughtful, researched ones that blend into the fields of cultural studies or historical nonfiction. On the other hand, publishers seem to be snapping up book proposals from people who have one big qualification to write a memoir: They're famous.

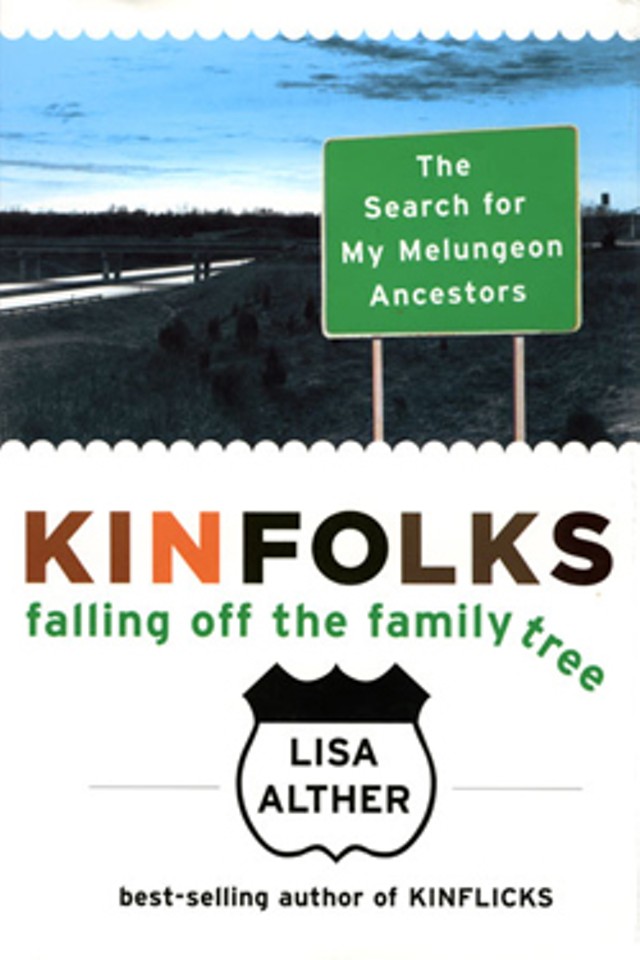

It seems unlikely that one book could exemplify both these trends, but Lisa Alther's first memoir, Kinfolks, does just that. The title is an allusion to the main source of Alther's name recognition: her 1976 novel Kinflicks, a bawdy best-seller about a Southern girl's coming of age. (Since then, the part-time Hinesburg resident has published four more successful novels, one of them set in Vermont.) Kinfolks traces the central events of Alther's life, covering much of the same ground as Kinflicks but showing us where the author diverges from her heroine. In this familiarity, and in the somewhat random anecdotes with which Alther seasons the narrative, it's hard not to see signs of a book written "for the fans."

Luckily, though, Alther has greater ambitions. As the book's sub-subtitle indicates, the author isn't just searching for her identity; she has a more specific quest in mind. Alther explains how when she was growing up in Tennessee, her paternal grandmother belonged to the Virginia Club, a sort of Southern Daughters of the American Revolution whose members touted kid-glove pedigrees extending back to the English Cavaliers. (Just to complicate matters, Alther's maternal relatives were proud Yankees.) But this affluent doctor's daughter was never brought to visit her extended Southern family - and wondered why.

In the 1970s, after she married and moved to Vermont, Alther began to suspect that she'd been distanced from her relatives because some of them were Melungeons, a once-isolated group of rural families who were at least "triracial," with mixed African, Native American and European ancestry. These stigmatized people had - and have - a common sixth-finger mutation that made them bogeymen in local folklore. Decades ago, Alther was warned that Melun-geons kidnapped naughty children. Now she wonders whether they haunt her own past.

And she keeps wondering. When Alther utters the "M-word" to her Virginia relatives, they clam up. Soon, though, she meets a prominent Melungeon scholar who turns out to be her distant cousin. In a multicultural society, being Melungeon, like being Native American, is suddenly "cool": Alther attends Melungeon conventions, combs through historical records, and frets over questions such as whether she has a "Mongolian blue spot." (You don't want to know where this is.) She discovers that historians can't agree on much of anything about this group, from the origin of its name to the ethnicities it encompasses - Turkish? Portuguese? Cherokee? African? Croatian?

Her research all leads to the bracing - if not particularly surprising - conclusion that Americans were a bunch of mutts long before the "melting pot" heated up with the 19th-century infusion of European immigrants. As Alther puts it, "It's a shame our founding fathers chose to portray the fledgling United States as an outpost for wayward Anglo Saxons, rather than as the panglobal mosaic it really was. Our resulting history might have been less grim." It's a fascinating subject and a worthy one, rife with irony - consider that Virginia, an early hotbed of interbreeding, later imposed draconian standards of racial "purity" and outlawed marriage across those lines.

Unfortunately, this is a book in which the destination is more interesting than the journey. Alther struggles to find a way to make the famous-writer's-memoir format mesh with the exceedingly complex web of historical clues she's weaving. As a result, the second half of the book sinks into travelogue: The author visits Colonial and Civil War sites; crosses the Atlantic in a windborne vessel as her ancestors might have done; explores Portugal and even Turkey in search of that intangible sense of I belong here.

Stylistically, it's a bit like being shown slides from your genealogy-obsessed relative's vacation. Alther hasn't yet mastered the art of structuring a long went-there-did-that narrative so the details don't blur. She uses humor to leaven the recital of facts, but the humor feels creaky - and, considering the story is all about dissecting cultural stereotypes, she's surprisingly dependent on them. Alther is prone to making comically sweeping distinctions between groups of people - English and French, Southerners and Northerners. In one passage, she admires the "busy and fit" boaters and athletes on Lake Champlain, then contrasts the scene to a NASCAR race in Tennessee, where "The BMIs (body mass index) of most spectators probably exceeded their SATs." (Leaving aside the accuracy of this assessment, it's worth noting that Vermont has its share of NASCAR fans - some of whom, who knows, might even double as buff windsurfers.) The book is peppered with this kind of stale ba-da-bing humor: "I remember the year we ate the cow named Lisa. So do my therapists."

As a personal memoir, then, Kinfolks doesn't showcase Alther at the top of her craft. But as a chronicle of one woman's attempt to uncover a lost chapter in American history, it's worth exploring. As a novelist, Alther can do what most historians can't: She asks why people cling so tightly to indefensible myths about their origins. Perhaps, she speculates, "The problem with not knowing who you are is that you become an empty vessel . . . That's probably why most people cling so desperately to the identity that's been handed them, even when it's false."

**********

From Kinfolks:

One night I find myself attired in a white strapless Scarlett O'Hara gown with a hoop skirt, waltzing at the country club with a tuxedoed and cummerbunded Harold. I'm taking as much pleasure in my Merry Widow corset and satin spike heels as I used to in my shoulder pads and cleats. I, too, am now proud of the Tidewater land grants my fine colonial ancestors received from King James I. My grandmother sits at a table with my parents, smiling like the Cheshire cat in her sequined gown.

Meanwhile, my sister Jane has been born with an olive complexion. Swaddled in a flannel blanket, she resembles a papoose. My mother, descended from New England Puritans, once proclaimed the idea of extramarital sex as unappetizing as using someone else's toothbrush, so there's no possibility of genetic intervention by some Native American milkman. Years later, when a plausible explanation emerges, some acknowledge having noticed Jane's exotic coloring. But at the time, as in all polite southern towns, no one says a word.

More By This Author

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of Book Review

-

Review of Sen. Patrick Leahy's New Memoir

Aug 26, 2022 -

Book Review: Pete the Cat and His Magic Sunglasses

May 27, 2016 -

Book Review: Penguin Cha-Cha

Mar 31, 2016 -

Book Review: Dog vs. Cat

Dec 16, 2015 -

Book Review: The Hummingbird by Stephen P. Kiernan

Nov 4, 2015 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.