Published November 18, 2009 at 8:59 a.m.

Back in 1997, novelist David Foster Wallace reviewed John Updike’s latest for the New York Observer under a headline that asked, “Is This Finally the End for Magnificent Narcissists?” In his review — later republished as an essay — Wallace coined the term Great Male Narcissist (G.M.N.) for writers such as Updike and Philip Roth, explaining, “I think the major reason so many of my generation dislike Mr. Updike and the other G.M.N.s has to do with these writers’ radical self-absorption, and with their uncritical celebration of this self-absorption both in themselves and in their characters.”

While the G.M.N.s went to great lengths to shun conformity and conventionality, Wallace continued, his Generation X contemporaries seemed to “have different horrors, prominent among which are anomie and solipsism and a peculiarly American loneliness: the prospect of dying without once having loved something more than yourself.”

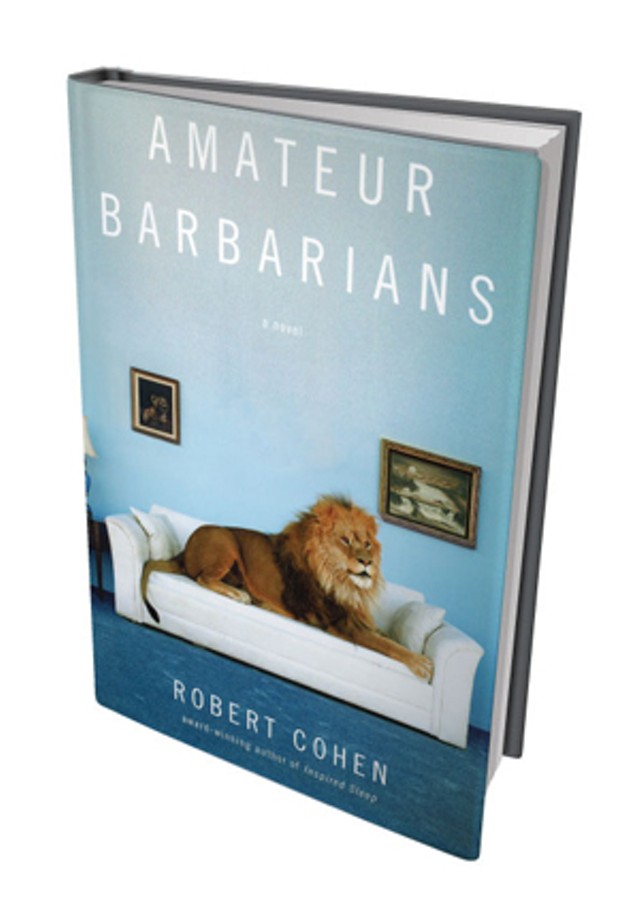

I quote this piece at length — 12 years later, when neither Updike nor Wallace is still with us — because it manages to anticipate with uncanny precision my own mixed reactions to Middlebury professor Robert Cohen’s latest novel, Amateur Barbarians. It sheds light on some of the themes of that work, too.

Cohen devotes so many pages and so many beautifully wrought sentences to exploring the mind of a “magnificent narcissist” — protagonist Teddy Hastings, a small-town middle-school principal in the throes of a midlife crisis — that he makes it clear the species is far from extinct. But by giving (roughly) equal space to a younger character who seems designed to represent Wallace’s irony-addicted, noncommittal generation, he also crafts a built-in rebuttal to the familiar critique.

Most readers will know whether they want to finish the book by the end of the first chapter, which takes 19 pages to detail the thoughts that afflict Teddy Hastings during his morning workout. Fifty-three years old, just a year past losing his younger brother to melanoma, he can’t ignore the intimations of mortality. He’s on sabbatical from his job and fresh from a stint in the local jail, for reasons Cohen slowly unveils over the ensuing chapters.

Unlike the iconic protagonists of Updike and Roth, Teddy hasn’t been an adulterer or a philanderer, or even — until recently — a rebel against convention. He’s been a loyal husband (who’s still attracted to his wife), a good father and an exemplary worker. But now he’s wondering what else there is. Cohen writes:

At his age a man shifts his focus, from the romance of building to the hard facts of maintaining. The building has all been done. Even if the nails are bent or mutilated and nothing is quite level or plumb or square. The building has been done; no room for more unless you tear something down. And he had no desire to tear things down. The hard thing was to keep them aloft. The tearing down came anyway; no need to contribute to that. Yet in the end one always did, it seemed.

This passage illustrates Cohen’s consummate control of his prose: the singing repetitions of phrase that echo the circularity of Teddy’s preoccupations; the bone-dry humor — and foreshadowing — of the last line. But it also illustrates Teddy’s magnificent narcissism; his inability to see beyond his own dilemmas. Does every man of a certain age really have a “building” to maintain, whether in a metaphorical or a literal sense? What about the failures, the names on foreclosed mortgages, the people who couldn’t even get their hands on a hammer and nails?

Cohen doesn’t let us forget that Teddy is a privileged fellow. (He lost some of my sympathy when he complained of feeling encumbered by his 32-inch flat-screen TV.) But we also see the other side, particularly toward the end of the novel, when Teddy treks to Ethiopia to visit his grown daughter. There, still bemoaning American abundance in the desert, he encounters a man who “seemed incapable of understanding how a too-big house could be something to complain about.”

Then there’s the character Cohen has designed as Teddy’s opposite, 33-year-old Oren Pierce, who steps into Teddy’s job — and, later, his lonely wife’s bed — in his absence. Oren is equally a product of American affluence, but he has no “building,” or even a foundation, to show for his relatively charmed existence.

A perpetual grad student, Oren has passed time in various metropolises becoming a connoisseur of everything and an expert in nothing, until an effort to revive a failed relationship brings him to the rustic college town of Carthage. (Middlebury town boosters may want to skip Cohen’s unsparing description from a New Yorker’s point of view: “[T]he restaurants were awful, the movies crap, the bookstore a joke...”) Here Oren stays, embracing the boredom, because he suspects that “was how you went about the maturity business, by saying no to some things and yes to others.”

So the thinker and the doer switch places: Teddy, who’s been toiling all his life, stops to ask Why? while Oren, who’s never felt obliged to do much of anything, experiments with bourgeois drudgery at the middle school. The problem is that, while the two men’s problems differ, their voices, as conveyed in Cohen’s leisurely, erudite, third-person prose, sound remarkably the same. The book noticeably lightens up only in a chapter told from the point of view of Teddy’s teenage daughter, Mimi.

But to Cohen, the difference between the generations seems to matter a good deal. Like the archetypal thirtysomething described by Wallace, Oren is horrified of self-absorption and solipsism and anomie; he’s eager to find someone he can love more than himself. But — and perhaps this is the third-act twist Wallace didn’t mention — he fails, because solipsism and self-absorption and anomie are in his bones. He no sooner gains an object of his desire, such as Teddy’s arch and distant wife, Gail, than he finds the desire receding.

While Cohen pokes fun at Teddy’s reckless impulses and overweening pretensions throughout the book, it’s difficult to escape his conclusion: The middle-aged boor has a constructive (and sometimes destructive) forcefulness that doesn’t seem to be in the sensitive young dude’s DNA. Teddy’s building may be leaning, but at least he’s built something.

Score one for magnificent narcissists. Cohen’s novel is far from the “uncritical celebration” of self-absorption that Wallace deplored in Updike; it’s nothing if not self-aware. Still, over its 400 pages, I couldn’t help being reminded of Mimi’s caustic view of her moody, demanding boyfriend, whose dialogue she translates in her head as “Me me, me me, don’t I feel good?” or just “Me me! Me me! Me me!”

That’s not to imply the novel needs a female perspective, per se — women are no slouches when it comes to solipsism. And many of the insights that emerge from Teddy’s soul-searching are meaningful to any reader, particularly when Cohen unsentimentally describes the experience of watching a brother die and knowing the old sibling rivalries will remain forever unresolved.

No, it’s generally not the ruminations themselves but their sheer weight and volume that made me want to escape from the thudding rhythm of Me me! Me me! in this accomplished novel. Amateur Barbarians imparts indelible images. (The long description of Teddy watching his daughter sleep on a summer afternoon combines innocence and eroticism like a Rousseau painting.) But the novel also, wonder of wonders, makes me almost grateful for our current hard times.

Because, when you’re scrambling to keep a roof over your head, there’s not a lot of time to worry about the creaks in the walls and rumbles of the plumbing. Like the aristocratic heroes of those old Gide and Bowles novels, Teddy has to wander deep into the desert to regain the alert leanness of the predator; to experience life in all its intoxicating “particularity.” Perhaps bad luck and bad credit will make seasoned barbarians of us all.

Want to judge for yourself?

Amateur Barbarians by Robert Cohen. Scribner, 401 pages. $27.

Robert Cohen reads from Amateur Barbarians in Misty Valley Books’ Vermont Voices 2009 series on Sunday, November 22, at 2 p.m., at the First Universalist Church in Chester’s Stone Village. Free. Info, 875-3400.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Middlebury: What to See, Do and Eat During the Eclipse

Mar 6, 2024 -

In Terms of Registering to Vote, Midd Kids Are Top of the Classes

Feb 28, 2024 -

19th-Century Educator Alexander Twilight Broke Racial Barriers, but Only Long After His Death. It’s Complicated.

Sep 20, 2023 -

Ninth Annual Middlebury New Filmmakers Festival Features Themes of Perseverance

Aug 16, 2023 -

Formerly Incarcerated Women to Find Work and Housing Through a New Program

Mar 8, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.