Published March 4, 2015 at 10:00 a.m.

William T. Ramage, an emeritus professor of art at Castleton State College, came to Vermont in 1971 as a "hippie refugee," as he puts it. He'd been teaching at Ohio State University in Columbus when riots broke out there and National Guardsmen killed four students at Kent State University during an antiwar demonstration. The events threw Ohio's university system into tumult, mirroring that of a troubled country. Ramage left the school and never expected to get another job in academia, he says.

Finding the position at Castleton was a stroke of good luck — and Ramage ended up teaching for 37 years. Although he officially retired in 2007, he still serves as an adviser for the department and the college's galleries. "I've had about 5,000 students," he estimates. "They've given me the opportunity to have a purposeful life."

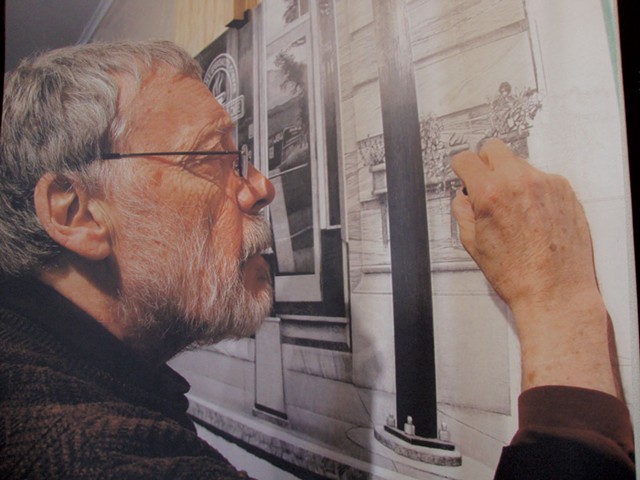

So, arguably, has creating his own art. Ramage tends to work in large-scale installations, which have been exhibited around the region and as far away as Kiev, Ukraine. Currently, he has two unrelated exhibitions in Rutland: "Death and the Chair" by Ramage and Bob Johnson; and "Rutland: A Post Piero Ideal City." The latter, a life-size combination of drawing and sculpture, was drawn from photographs taken in Rutland at 5:30 a.m. on a Sunday, in the absence of car and foot traffic. The result is almost like seeing the city's Merchants Row as it was in the 19th century.

The installation consists of 32 panels, 43 by 10 feet in total dimensions. The drawing on each panel depicts two photographs, the buildings drawn within two to three millimeters of scale. At the top, a traffic light protrudes, pushing the height to 11.5 feet in that section. It's part of Ramage's vision of Rutland as an "Ideal City," riffing on a concept developed by the 14th-century Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca, whose urban vision was characterized by its sophisticated use of linear perspective.

But Ramage isn't trying to make the world's largest graphite drawing, or to impress viewers with an idealistic panorama of Rutland. For him, as he explained to Seven Days, it's all about seeing, understanding how the brain helps us see, and talking to people about those ideas. The art exists to create a conversation.

Why do you want to be present when people see "Rutland: A Post Piero Ideal City"?

You could look at it and see a panorama or a big dumb rendering of Rutland and not realize that it's really life-size. In my mind, it's an exercise in a total alternative to linear perspective, where you have a horizon and a vanishing point way out in the distance. Here, [imaginary lines] start way out in the painting and come toward you. The vanishing point is where you, the observer, are standing — where our eyes are — rather than somewhere out in infinity. When you stand [facing the midpoint of the drawing], every 29-inch panel of the drawing is aimed right at that spot. It literally turns linear perspective inside out. It causes a different way of seeing and understanding space.

The drawing [exists] so I can have this conversation with people. This whole thing is not exactly what you thought it was. This might not be art. I think of myself almost more as a theorist and a soothsayer. It's because of the centripetal perspective, which means to move everything to the center, to the mind where everything ought to be. It's a thought process, not just a phenomenological experience.

What's in it for you?

I wanted to experience being in a pencil drawing, so it had to be life-size. When you stand on this rug [facing the drawing], you're standing on the exact same spot where the photographs were taken. I didn't make it just to make a big drawing. This cutout [a freestanding cutout drawing of Ramage] is life-size, and the drawing is life-size. I can move him anywhere in the room, and he will be proportionate to the drawing.

So what's the science behind this?

For the past 30 years, you could relate most of my work as much to science as to art. This [centripetal perspective] is more the way we see than linear perspective. Did you know that the brain makes up what you see? One neuroscientist calls it the brain's dark energy. Visual information is infinite, but let's say 10 billion bits of data per second come into the retina. The optic nerve can only bring in six million bits per second; then it goes to the visual cortex, where only 10,000 bits can be handled. When it gets there, it's [still] not a picture. By the time it reaches 30 other points in the brain, there are only 100 bits. That's not enough of a stream to produce a conscious perception, so the brain makes it up. The brain organizes itself so it can present external information coming in as something that's coherent. This is true for everything, not just perception.

But linear perspective has had a profound effect on Western culture.

Tell me about your other exhibit, "Death and the Chair." What do we talk about when we talk about death?

The problem with the word "death" is, it has all this baggage — skulls and crossbones and a guy dressed in black. It might be a happy thing. "Death and the Chair" is not dark. It's all quotes and thoughts.

Death is something other than dying. You're not dead until you're done dying. It's an abstraction. So many people say they don't understand abstractions, but dying is an abstraction. I realized that my death is always with me — so much so that I decided to call it Winston. I've had different relationships with Winston. In my twenties, I was indifferent. He didn't occupy any part of my real mind. Then, in my late twenties through forties, he became menacing. I think I contracted about every terminal disease in my mind [during those years].

In my forties, he became a co-conspirator. He was helpful. When I was working on a series of head drawings, something happened in my own head that said, You have to commit yourself to doing this perception stuff. Period. Since I was 40, I've been obsessed with perception. I also started making chairs when I was 40. From my sixties on, I have no fear about death itself. Dying scares the shit out of me.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Doors of Perception"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Sculptor Clark Derbes Gives New Life to Fallen Wood

Jan 10, 2024 -

A Spate of Rural Homicides Puts Residents of Small Vermont Towns on Edge

Nov 1, 2023 -

Christina Watka’s Installations at Soapbox Arts Dazzle the Eye and Mind

Nov 1, 2023 -

Montréal Museum of Fine Art Revisits the Work of Midcentury Art Star Marisol

Oct 18, 2023 -

Readsboro Artist Sienna Martz Gains a Following for Her Ethical Wall Sculptures

Oct 3, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.