Published March 27, 2013 at 4:01 a.m.

Vermont composers of contemporary classical music are about to gain well-deserved home-state exposure. The professional choral group Counterpoint and the Vermont Contemporary Music Ensemble will both perform concerts dedicated to the work of living local composers on the first weekend in April. As it happens, most of those composers are men — four out of five on VCME’s program, and five out of six on Counterpoint’s. Which raises the question: Where are the women?

To be fair, this gender imbalance reflects the national picture. The League of American Orchestras’ annual statistics reveal that works by women of any era make up about 1 percent of programming. A casual survey by the online forum NewMusicBox found that new-music groups program women’s compositions between 8 and 28 percent of the time.

Reasons for the gap are debatable, as they are in any field that has failed to reach gender parity since feminism’s second wave. But a handful of Vermont’s female composers say what matters to them is that the situation is improving steadily.

Take 91-year-old Margaret Meachem of Dorset. The Bennington College graduate studied composition with one of the 20th century’s most renowned pedagogues, Nadia Boulanger. Her commission in 2000 from the Manchester Music Festival was performed by four Metropolitan Opera singers, and the Kiev Chamber Choir recorded her work in 2006. Yet for much of her composing life — which continues today, slightly hampered by spinal stenosis — Meachem had to submit works for competitions under a male pseudonym.

“Women were simply not considered,” she explains. In the 1960s, Meachem went to Washington, D.C., to hand-deliver a submission for a National Council on the Arts scholarship. “I walked into the building, and the man said, ‘Oh, it’s very competitive,’ and he wouldn’t even take my work,” she remembers. “And that wasn’t uncommon.”

Meachem recalls when “a famous British conductor announced on the radio that women did not have the ability to be composers” — that was Sir Colin Davis in the 1970s. Not surprisingly, when the International League of Women Composers (now the International Alliance for Women in Music) formed in 1975, Meachem joined.

She helped found the Consortium of Vermont Composers in 1988. The prolific experimental composer Dennis Báthory-Kitsz of Northfield spearheaded the consortium, and his efforts helped bring to light women composers around the state. Among them is Lydia Busler-Blais of Montpelier, the sole female composer on the upcoming VCME program, though the group has played many women’s works over its 25-year history. “We’re very keen on supporting Vermont composers,” says artistic director Steve Klimowski, who adds that he learns of them “by word of mouth almost exclusively.”

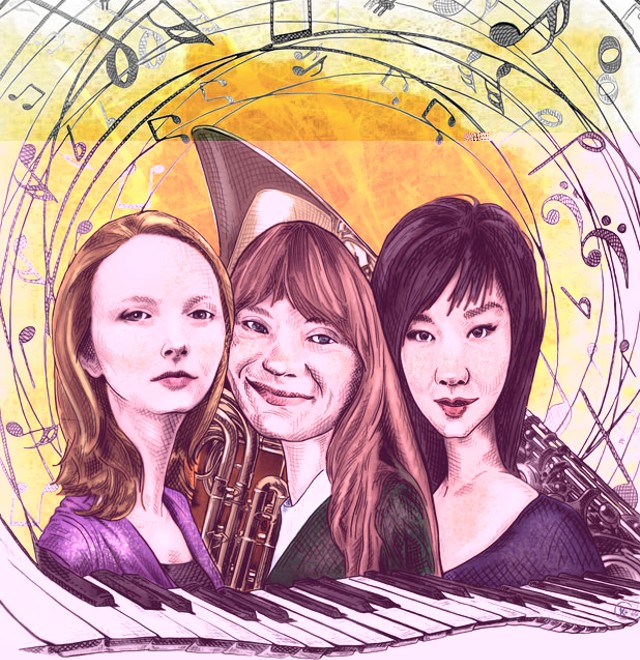

Busler-Blais, 42, is a horn player who began composing as a child, trained at the New England Conservatory and played in the Manhattan Chamber Orchestra, among other New York ensembles, before moving to Montpelier in 2000.

Because she plays horn around the country, Busler-Blais has managed to get her work programmed, and occasionally commissioned, through fellow musicians. She likens her situation to that of Kathy Wonson Eddy, a composer and former pastor of the Bethany United Church of Christ in Randolph, whose church community literally gives voice to her works. It’s an advantage other composers say they regret not having. As Essex composer Mary Elizabeth, 57, notes, “It’s really hard and expensive to actually hear what you write.”

Though Busler-Blais doesn’t belong to women’s groups such as IAWM, she does attend the Women Composers’ Festival of Hartford [Conn.]. Such events are needed, she says, because attendees “may get a commission and make a living out of this, which not many women do.”

More may soon, to her thinking. “Composing is one step behind orchestral players,” Busler-Blais avers. That is, orchestras used to be all male; it took 30 years of holding first-round auditions behind a curtain for them to reach gender parity. Busler-Blais herself has watched the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra’s horn section go from all men to today’s gender-balanced mix.

Busler-Blais notes that the women who are currently being programmed the most, such as Joan Tower and Jennifer Higdon, are “being played over and over because they have name recognition.” But in general, she says, “There’s a lot more exposure for women composers now. And the ones who are visible now have to be composing for a while before the younger ones want to continue to compose.”

One measure of how far women have come is a story offered by Su Lian Tan, a 49-year-old internationally recognized composer, flutist and Middlebury College professor. Tan writes what she admits is “rather difficult” music for highly accomplished musicians, and counts the Hungarian composer György Kurtág among the living composers she most admires. When the acclaimed Takács Quartet, which originated in Hungary, came to Middlebury 12 years ago, it chose to commission Tan over a work from Kurtág. The result was her 2003 string quartet “Life in Wayang.”

Tan grew up in Kuala Lumpur and played flute in the Malaysian Philharmonic’s precursor as a teenager. After a stint in London, she moved to the U.S. to study at Bennington College, where, as a music major, she was required to take composition. Her first composition teacher was the venerable Vivian Fine. “That was my first encounter with the notion that perhaps a composer could be female,” she says.

Though uncomfortable with the phrase “woman composer,” Tan admits a recent work, the opera Lotus Lives, is both deeply personal and “entirely about women’s issues.” In it, two female friends, one based on her grandmother, sing an aria about the worldly success they desire for their future granddaughters.

Tan is currently in discussion with WGBH Boston to produce a DVD of the opera that will be broadcast on the TV station. As for women composers in general, she muses, “We’re still a novelty, still considered not quite at par. I really don’t know why.” Perhaps it’s simply “indicative of the larger culture,” she continues, adding that she was the Middlebury music department’s first female chair only about a decade ago. Or, Tan suggests, “Perhaps we’re underrepresented because there are actually fewer of us.”

Sara Doncaster, an Irasburg resident who has been directing the annual Warebrook Contemporary Music Festival there since founding it 23 years ago, offers a similar explanation: “It’s just left over from the old culture of composition being a man’s field.”

Doncaster, 48, began studying composition at Boston University after tendonitis forced her to take a break from her piano-performance major. When she went on for advanced degrees at Brandeis University, she was the only female theory-and-composition candidate in the program for three years.

Doncaster has written four major song cycles and begun an opera for her favorite Met Opera tenor, Jon Garrison, among many other works. She teaches band, chorus and music theory at Lake Region Union High School. Not surprisingly, when Nathaniel Lew, artistic director-conductor of Counterpoint, asked her to submit a work for its upcoming concert, she couldn’t find the time. “I had a PDF of a work I could have sent to the printer and had mailed to him. I had work done! I’m just really busy,” she says.

Lately, composer Peggy Madden, 60, of Windsor, hasn’t even had the time to compose. Madden is a high-school paraprofessional who began composing later in life in the electronic-acoustic field — a surprisingly male-dominated specialty, she notes. She was one of several women contacted for this article who have had to put aside composing to make a living.

But Madden has seen signs that augur well for future gender ratios in music programming in her 17-year involvement with the online composition forum Music-COMP (formerly Vermont MIDI Project), part of which she spent mentoring young composers.

Through Music-COMP, students can submit working drafts of their compositions and receive ongoing feedback from an established composer on staff. Twice a year, the nonprofit chooses the best of the finished pieces to be performed in concert. Currently, the project has 130 submissions, says senior mentor Erik Nielsen.

Nielsen says roughly equal numbers of boys and girls in elementary and middle school submit works. “If there is a shortage, I must admit that it will more often be of high school girls than of males at any level,” the Brookfield composer observes, though he adds that this year’s high school composers are “pretty close to 50-50.”

Music-COMP founder-director Sandi MacLeod says, “We’ve always had to work a little harder to encourage girls in middle and high school. At a certain age, their attention turns to other things, or they lose confidence.”

One young composer who hasn’t lost confidence is Harwood Union High School senior Cecelia Daigle of Moretown. The 18-year-old pianist began submitting compositions to Music-COMP in fifth grade. Soon she started “fiddling around on a lot of instruments” to learn how to write for them. Two years ago, the VCME premiered her work Mortal Fools, and last weekend the Vermont Philharmonic presented her piece for full orchestra, Cataclysm.

“It was amazing,” Daigle says matter-of-factly. “I’ve never heard that many people playing my pieces before. The VCME piece was for five instruments; the Philharmonic has 72.”

Daigle is headed to the Berklee College of Music in the fall. One day, she may be tapped for a Music-COMP retrospective like the one MacLeod is currently writing, which contains career updates on the “most memorable” composers to participate in the program between 2000 and 2011. MacLeod contacted 29 alums, 12 of them women, and ended up compiling notes on 25 — nine female.

“That’s 36 percent,” MacLeod says. “That’s pretty good!”

Counterpoint performs “There Alway Something Sings: New Choral Works by Vermont Composers” Friday, April 5, 7:30 p.m., at McCarthy Arts Center, Saint Michael’s College, Colchester; Saturday, April 6, 7:30 p.m., at the Unitarian Church, Montpelier; and Sunday, April 7, 4 p.m., at the First Congregational Church, Manchester. $20. counterpointchorus.org

Vermont Contemporary Music Ensemble performs “Lovely After All These Years” Friday, April 5, 8 p.m., at Bethany Church, Montpelier; and Saturday, April 6, 8 p.m., at Black Box Theater at Main Street Landing, Burlington. With Vermont poet laureate Sydney Lea. Tickets at the door only; $25. vcme.org

This article was titled "Scoring Points" in print.

More By This Author

Speaking of Music, classical

-

Two Local Band Directors March in the Macy's Parade

Nov 22, 2023 -

Before a Burlington Show, the Wood Brothers Get Back to Basics

Oct 26, 2023 -

After a Half-Century of Leading Local Ensembles, Steven and Kathy Light Prepare a Musical Farewell

May 3, 2023 -

Double E 2023 Summer Concert Series Kicks Off With the Wailers

Mar 17, 2023 -

UVM’s New School of the Arts Gathers Many Creative Disciplines Under One Roof

Sep 14, 2022 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.