Published August 4, 2010 at 6:39 a.m.

When Randy Brock was campaigning for election as auditor of accounts, he tried to educate voters about the office he wound up winning in 2004 — one of five constitutionally mandated offices elected statewide in Vermont. “The job of the auditor,” Brock quipped, “is to protect you from the other four.”

But who watches the watchdog, especially if he shows signs of distemper?

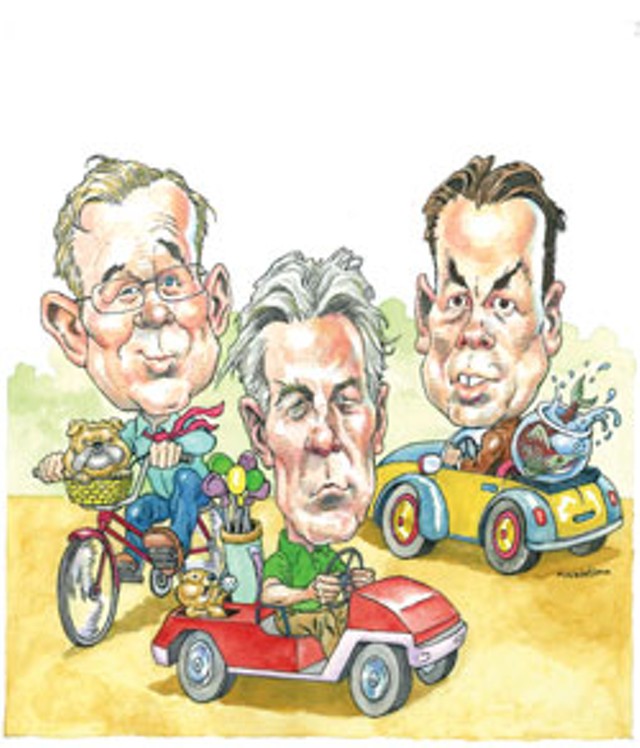

Currently, three major-party candidates are vying for the job: two-term incumbent Tom Salmon, who’s unopposed in the Republican primary; and challengers Ed Flanagan and Doug Hoffer, who will square off in the August 24 Democratic primary. Michael Bayer of the Progressive Party, Michael Dimotsis of the Working Families Party and Jerry Levy of the Liberty Union Party are also on the ballot, though none of the three is considered a serious contender.

How do Vermonters usually choose an auditor? Since most voters don’t have the time, skill or desire to pore over the auditor’s reports — most are long, full of minutiae and dry as toast — candidates are typically judged on their character.

“Above all,” adds Brock, who considered challenging Salmon in the Republican primary, “an auditor has to be credible, so that the people who are dealing with that person believe in that person’s integrity and independence.”

Is familiarity a prerequisite for credibility? The two candidates with the most name recognition and money — Flanagan and Salmon — have tarnished their respective reputations. But a clean record and the right qualifications may not be enough to propel Hoffer to the top. The 59-year-old policy analyst, who has never run for statewide office, admits he does not see himself as a politician. But here in Vermont, before the auditor can settle down to the task of professional number crunching, there is the matter of campaigning for, and winning, votes.

Hoffer worked for Flanagan when he served as Vermont’s auditor for four terms, from 1993 to 2001 and, like most people, he gives the former auditor credit for raising the job’s profile from high-paid rubber stamper to public watchdog. But that was before the near-fatal car crash in the winter of 2005 that left Flanagan with a traumatic brain injury. Flanagan was a state senator when his car went off the road late one night on the way back to Burlington from Montpelier. He spent almost a month in a coma and the next six learning to walk and talk again. When Flanagan returned to the legislature in May 2006, his resurrection was considered nothing short of miraculous.

But the “new Ed” exhibited some odd behaviors. In 2009, a patron at the Greater Burlington YMCA reported him for masturbating in the men’s locker room. Although Flanagan’s membership was revoked, the State’s Attorney opted not to file charges. The senator chalked up his in flagrante delicto to a diagnosis of disinhibition syndrome, which is common among brain-injury survivors. But the episode nonetheless raised doubts about his judgment.

More recently, Seven Days columnist Shay Totten revealed that Flanagan’s cycling habits are nearly as dodgy as his driving. In July, he had a pair of run-ins with moving vehicles — in two days. Neither resulted in serious injuries, and Flanagan blamed the fender benders on his new electric bicycle, describing the sensation of riding it to “walking on stilts.”

For his part, Salmon has also captured headlines for some moving violations. In November 2009, a state trooper stopped him for failing to use his turn signal. He was subsequently arrested for, then pled guilty to, drunk driving. Salmon lost his license for three months and paid an $876 fine.

Later, it was revealed that the auditor had been driving home from a fête in Stowe with members of his inner staff who were out celebrating their sizable pay raises. Those salary bumps came just as the rest of the auditor’s staff, and much of the state’s workforce, had been asked to absorb a 3 percent pay cut.

The only guy in the race with a clean driving record? Hoffer, who drives a 12-year-old Ford Taurus. He’s spent the last 17 years working behind the scenes as a self-employed public policy analyst. People who know Hoffer describe him as exceedingly bright, inquisitive and attentive to detail, with a good head for numbers.

“One of Doug’s strengths is that he asks different questions than traditional economists would ask,” says Ellen Kahler, executive director of the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund. When Kahler was executive director of the Peace & Justice Center in Burlington, she hired Hoffer as the principal reseacher for the “Vermont Job Gap Study,” which was released in successive phases beginning in January 1997.

“A lot of people say he’s got an agenda behind the data he produces,” Kahler adds. “But his only agenda is asking good questions and then accurately presenting information and analysis that attempt to answer those questions.” A willingness to speak the truth should be an asset for the state auditor, especially one who claims to have no higher political aspirations.

Hoffer’s weaknesses? He’s never held elected office. His only management experience was working as head maitre d’ of the legendary Alice’s Restaurant more than 30 years ago. Also, over the course of his career, he’s earned a reputation for a blunt and undiplomatic style, which has occasionally ruffled feathers in Montpelier. And in the media. Hoffer writes withering blog comments and regularly sends emails scolding reporters for not doing their homework.

Perhaps most importantly, Hoffer has yet to shift his campaign into high gear. He skipped the recent Fourth of July parade circuit, an opportunity for most statewide candidates to log critical face time with voters. An avid amateur golfer — he has a handicap of three — Hoffer is more accustomed to spending free summer moments on the links than pressing the flesh.

“This is one of the most bizarre statewide contests we’ve seen in recent years,” says Garrison Nelson, a political science professor at the University of Vermont. “You’ve got two candidates who are somewhat compromised and a third candidate who seems competent but, unfortunately, also doesn’t seem to want to campaign … It wouldn’t surprise me if this race ends up having the lowest turnout.”

******

State auditor may be the most important job nobody really understands. But with annual state expenditures of $4 billion, about $1.5 billion of which comes from Uncle Sam, it’s never been more critical to elect someone to that office who can assess whether taxpayers are getting the biggest bang for their buck.

What does the auditor do? Essentially, it’s his or her duty to monitor the internal controls that protect citizens from waste, fraud and abuse. The auditor weighs in on the overall fiscal fitness of the state and signs off on all financial audits the state generates, both the ones created in-house and those outsourced to the Big Four accounting firms.

Finally, after all the statutorily mandated audits are completed, the auditor has discretion to conduct performance audits of state departments, agencies and programs — basically, wherever state funds are spent.

For example: Is the state’s sex-offender registry up to snuff? Are pharmacies double-billing the state for drugs that Medicaid beneficiaries received? Are programs to reduce child sexual abuse having an impact? Are economic stimulus programs actually creating jobs?

Eric Davis, professor emeritus of political science at Middlebury College, suggests that incumbent auditors and treasurers rarely lose unless they’re perceived as “not acting to the standard of probity associated with that office.”

“The question for me is,” Davis adds, “do the questions about Tom Salmon — the drunk-driving conviction, conducting political activity on state time with state money, the periodic expletive-laden explosions — do they rise to that level?”

Salmon, the incumbent, declined repeated requests to be interviewed for this story. He said he’s not speaking to any reporters about this race until the outcome of the Democratic primary is known.

Silence could work to his advantage. In the past, he’s gotten into trouble for his loquaciousness. After his DUI arrest, Salmon held a rambling, hour-long press conference in Montpelier in which he touched on Los Angeles riots, Hurricane Katrina and where he was on 9/11, among other things.

Likewise, he got into an expletive-filled email exchange with Seven Days columnist Shay Totten that wound up getting reported in the press. “I’m wasting more state time on your political bullshit,” Salmon complained after telling Totten to “fuck off.” He later apologized, but the outburst left some wondering whether he had unresolved anger issues.

Salmon certainly has the right pedigree for higher office in Vermont: Like fellow Republican Lt. Gov. Brian Dubie, he’s a native Vermonter who still serves in the military. Salmon, 46, was born and raised in Bellows Falls. The son of former Gov. Thomas P. Salmon, he earned his bachelor’s degree in accounting at Boston College and learned auditing at the accounting firm of Coopers & Lybrand in Hartford, Conn., and Los Angeles.

In 1992, Salmon left a sales job with ADP payroll services in Los Angeles to teach in inner-city schools in East L.A. In 2002, he returned to Vermont to work as a special-education teacher for emotionally disturbed boys in Bellows Falls.

In 2006, the then-Democrat challenged GOP incumbent Randy Brock for the auditor’s job. With more than a quarter-million ballots cast, the initial count put Brock ahead by 137 votes. But a recount later gave Salmon the victory — the first such upset in Vermont history.

Salmon was considered a rising star when he arrived for work in Montpelier in January 2007, and he made no secret about his aspirations for higher office.

But in the ensuing years, Salmon’s star faded. In the words of one number cruncher who routinely deals with his office, the auditor has been “relatively invisible,” and has produced neither the volume nor quality of work of his predecessors.

Deputy Auditor Joe Juhasz refutes that claim. Though he acknowledges that “budget pressures” have forced the auditor’s office to operate with two fewer positions than what’s considered “normal,” he asserts that Salmon’s greatest achievement has been the “transformation of the office from a financial-auditing office to a performance-auditing office.”

Those audits include a December 2008 review of the Agency of Transportation’s rail division, which revealed that the state gave more than $7 million in no-bid contracts, including a single contract worth more than $4 million, to one railroad company.

In June, Salmon’s office released a performance audit of the state’s sex-offender registry that turned up “a sizable number of serious errors.” These included offenders who weren’t on the list but should have been, as well as people on the list who didn’t belong there.

In fairness, Salmon’s less-than-robust track record could be chalked up to his extended absences. Since 2008, he has missed at least 270 days of work, primarily due to his 2008 military deployment to Iraq with the U.S. Navy Reserve’s Construction Battalion, aka “Seabees.” He was overseas, on active duty, in the run-up to the 2008 election, during which Salmon was legally barred from campaigning.

Brock, who was expected to challenge Salmon, begged off because of that situation. The other two challengers, the Liberty Union’s Levy and the Progressive Party’s Martha Abbott, waged only perfunctory campaigns. Salmon was a shoo-in.

But not all of Salmon’s absences were combat-related. As one staffer in his office reports, he spends a lot of time out of state at conferences and conventions, noting, “Tom never met a conference he didn’t like.”

And, much to the chagrin of other members of his staff, Salmon also earned a reputation around Montpelier as someone who “shoots from the hip” and weighs in on policy matters without first doing his research or serious review of the data.

In May 2008, lawmakers were weighing a bill that would require Entergy, the owner of the Vermont Yankee nuclear plant, to put more money into its decommissioning fund. As this was occurring, Salmon agreed to meet with Entergy representatives in his office and let them plead their case.

Within 24 hours, Salmon sent a letter to legislators attacking the bill that Democrats had worked on for months. Republicans on the floor cited Salmon’s missive in their effort to kill it.

“What the hell did the auditor say when Entergy came to the door? ‘C’mon on in’” says Hoffer. “An auditor is not supposed to let people come to his office and lobby him.”

A few months earlier, several state senators had asked Salmon to look into the management of Vermont Yankee’s decommissioning fund. Although Salmon agreed to do the audit, it still hasn’t been released two years later. Juhasz says he expects it’ll be out “soon.”

Asking for anonymity, one staffer in the auditor’s office noted that office morale “hit rock bottom” during Salmon’s tenure, especially after the news broke about his legal woes.

No one was shocked when Salmon left the Democratic Party in September 2009. At the time, he explained that the switch was due to frustration over the Dems’ handling of the state budget. But Salmon’s announcement seemed more political than ideological. It occurred shortly after Gov. Jim Douglas announced he wasn’t running for reelection — and before Dubie announced his bid for that office.

Since then, Salmon has made it clear that he doesn’t see the auditor’s job as his final political stop. In May, he sent a letter to the Brattleboro Reformer in which he put Sen. Bernie Sanders on notice: “In your 2012 election, you will meet me or another qualified Republican candidate who is going to hold you accountable for this Green Ego Ride that you and many of our nation’s leaders are on.”

******

Historically, the Vermont auditor’s office hasn’t been much of a political springboard. Flanagan, one of Salmon’s two Democratic challengers, wanted to change that.

First elected auditor in November 1992, after a failed bid for attorney general, “Ed Flanagan took an office that was relatively invisible and moribund and transformed it into a major policy post,” says UVM’s Nelson. The Harvard-educated lawyer often challenged the Howard Dean administration’s political dealings and issued scathing reports, earning Flanagan the “bulldog” moniker.

But, despite four terms as auditor, Flanagan was never able to leverage that political capital to win higher office. In 2000, he lost his bid to unseat Republican U.S. Sen. Jim Jeffords. Two years later, he failed to get beyond the Democratic primary for state treasurer.

In 2004, Flanagan was elected to the state Senate from Chittenden County, where he’s served ever since — except for a six-month absence after his accident. Since then, there has been plenty of whispering among fellow lawmakers and other Statehouse regulars about Flanagan’s unusual behavior under the Golden Dome. As Seven Days reported in a May 20, 2009 cover story, several lobbyists and other Statehouse regulars expressed concerns that the senator’s erratic behavior was indicative of diminished mental capacity. Two months later, Totten broke the YMCA story.

Flanagan explains away the public masturbation incident as “a symptom of a brain injury which occurred five years ago,” during a recent interview in his Vermont House apartment in downtown Burlington. “It was the final symptom, but it was a symptom that people forgot to mention to me. But once I realized it was a symptom, I just decided to avoid it and I’ve never attempted to do it again.”

Asked if he’s still receiving ongoing treatment or therapy, Flanagan replies, “No, not really.” Flanagan continues to insist that his memory and intellect are intact. He describes his recovery in Phoenix-like terms, as the “Ed Flanagan who rose out of the ashes through very hard work … to rehabilitate myself and put myself back together … Some people don’t like it, but the old Ed Flanagan is back.”

Flanagan still speaks with a slight impediment and walks with an altered gait, though he seems more relaxed in person than he did last year. He says he no longer suffers the chronic back pain and other physical problems that caused some of his odd behaviors, such as lying down on the floor in committee rooms at the Statehouse.

“Personally, I don’t see much difference in Ed between now and then,” notes Nancy Bercaw, who worked with Flanagan when he was auditor in the 1990s. “He always had quirks and did things his own way … He could be very disagreeable, but he was aggressive on the issues that mattered to him and the state.”

If he gets his old job back, Flanagan says he’ll approach it differently. “When I first went to that office, I was rather impetuous,” he concedes. “Now, I’m more thoughtful. Even when I speak, I have to actually think” — a positive consequence of the rehabilitation, according to Flanagan.

What about the errors on his campaign finance reports? Hoffer recently busted both Flanagan and Salmon for inaccuracies on their forms.

Flanagan won’t speak ill of Hoffer, a former employee he describes as “a friend.” But he does say, “I was totally focused on my physical and mental rehabilitation. And, my political finances were … not [on] the highest list of priorities.”

Flanagan insists that he caught the “oversights” in his financial reports and brought them to the attention of the secretary of state. And about that other thing: a claim, despite clear evidence to the contrary, that his campaign hasn’t spent any money yet? Flanagan says, “We haven’t paid anyone yet.”

******

Hoffer says he doesn’t intend to attack Flanagan’s fitness in the weeks leading up to the Democratic primary. Instead, he hopes to convince voters that he’s better equipped to take on Salmon in November.

“I don’t think there’s any question that I’m as qualified as he is,” Hoffer says of Salmon during an interview in his condo near Oakledge Park in Burlington. “I’ve spent the last 20 years doing numbers. And, as far as the legislature is concerned, I’ve spent the last 20 years providing them with numbers, too.”

The question is whether a no-nonsense guy who eschews soundbites and broad generalizations can convince Vermont voters of the same.

As Hoffer discusses his vitae, he frequently uses the language of a policy insider, dropping names and acronyms as if they’re commonly known. But, on the rare occasion when he does speak about the auditor’s job in layman’s terms, he gets straight to the point.

“Financial auditing is critical. It’s part of the core mission of the office,” he explains. “But it’s not the end of the discussion. It’s the beginning.”

Hoffer grew up in Fairfield County, Conn., until his family moved to Florida. He quit high school in the middle of his junior year and got his GED a few years later. As he recalls, “It was a great investment of $7.50. Saved me a year and a half of high school.”

Hoffer didn’t enter college until he was 29, on a full scholarship to Williams College. He had to check with the National Collegiate Athletic Association to make sure he wasn’t too old to play on the college golf team.

Hoffer graduated in three years, then attended law school at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo School of Law and Jurisprudence. He had no intention of practicing law, but saw it as a great preparation for public policy work. “I’m not the kind of guy who ever wanted to get up in the morning and say, ‘May it please the court…’”

In 1988, Hoffer was hired for the only job he applied for — policy analyst for Burlington’s Community & Economic Development Office. There, he claims, he was “the first one in CEDO to recognize the true value of the Intervale.”

Hoffer left CEDO in 1993 when Mayor Peter Clavelle lost to Peter Brownell. In 1995, he went to work for Flanagan as an independent consultant in the auditor’s office, where he did performance reviews and compliance audits. Hoffer was the principal author of the first audit on the Vermont Economic Progress Council. He’s never stopped demanding the public should know which Vermont companies are getting economic incentives from the state, and whether they actually live up to their job-creation promises. He’s described various reports issued by the Douglas adminstration as “garbage.”

Not surprisingly, he was also critical of the governor’s Challenges for Change initiative, in which department and agency heads across state government were asked for recommendations to cut positions and programs. He contends that the administration lacked adequate information to gauge the effectiveness of those programs — the kind of information any good auditor should have turned up.

“They needed good information and they didn’t have it,” Hoffer contends. “If this were a report turned in by a high school student, they’d send him home.”

When he scolds Salmon, Hoffer is more pointed. He notes the auditor’s use of his office to delve into the finances of municipalities. “That’s a fine sentiment,” says Hoffer, “but it’s not the job of auditor.”

Auditing VISION, the state’s accounting software, may have been a good idea, he concedes. The process uncovered a duplicate payment of $265,000. But Hoffer claims the state had already identified about $200,000 in overpayments, so the actual savings was only about $65,000.

Was the audit worthwhile? Hoffer can’t say because, as he points out, none of Salmon’s reports indicate how much the audit itself cost. But, as he suggests, “I wouldn’t be surprised if that audit cost more than $60,000.”

Hoffer chooses his words carefully, but doesn’t mince words when he’s on the attack. He’s publicly referred to Kevin Dorn, secretary of commerce and community development, as “a tool,” and observed that Howard Dean could sometimes be an “asshole.”

“If I’ve been less than politic, it’s because I wasn’t a politician,” Hoffer says of his past life, without promising to be any more diplomatic in the event he is successful in the primary. “I think it’s fair to say that, if asked, most voters would say, ‘We want an auditor who’s not afraid to speak his mind on our behalf. We want someone who’ll stand up and say the emperor has no clothes.”

Don’t be surprised if all three candidates wind up pointing at each other.

*** Correction: The print version of this story said that Doug Hoffer went to law school at the University at Buffalo.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives

Apr 22, 2024 -

Man Charged With Arson at Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 7, 2024 -

Police Search for Man Who Set Fire at Sen. Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 5, 2024 -

Bernie Sanders Sits Down With 'Seven Days' to Talk About Aging Vermont

Apr 3, 2024 -

Progressive Burlington Mayor-Elect Mulvaney-Stanak Won by Picking Up Democratic Votes

Mar 12, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.