click to enlarge

- Library of Congress

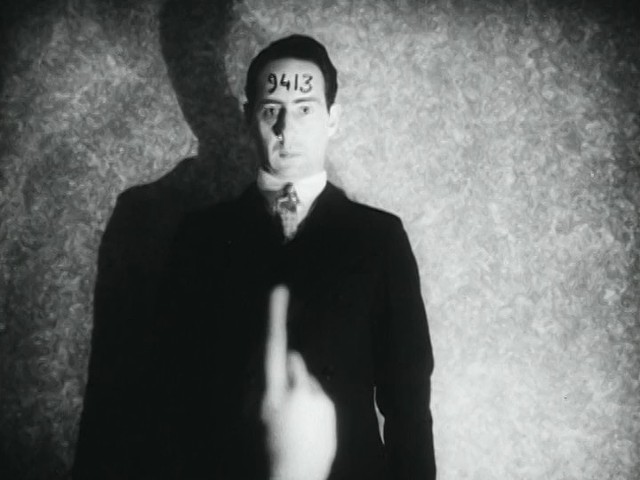

- It ain't easy being an extra: "The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra"

Supposedly, something like half of the films made before 1950 are lost forever, the victims of quick-decaying nitrate film or indifference to their artistic and historical value. That's a

lot of lost films, and it causes me no end of sadness that they're done. But my tears dry up when I marvel at the fact that among the survivors are some pretty unlikely films.

One film that is, thankfully, in no danger of disappearing from the earth is "The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra," directed in 1928 by

Robert Florey and

Slavko Vorkapich. That's a small miracle, as this odd and inventive short film was allegedly made for less than $100, mostly for the purpose of amusing the filmmakers' friends. It's essentially a low-budget home movie with an avant-garde streak.

It's the kind of film that, were it made today, would be likely to slip through the cracks. But "9413" (as I'll henceforth refer to it) was made right as films were shifting from silent to sound, and its young makers would soon prove themselves to be stupendously talented, its place in history assured. In 1997, the film was selected for inclusion in the Library of Congress'

National Film Registry, which thus bestowed on it the federal stamp of legitimacy. As well, it's been included on two important DVD anthologies of avant-garde films, Kino's

Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and 1930s and the superior

Unseen Cinema. This film isn't going anywhere; now that it's on the internet, you can watch it right now. Take 15 minutes and check it out.

It's a great thing to be able to call up, with the click of a mouse, one of the masterpieces of the first wave of avant-garde cinema. In its story, "9413" is actually less avant-garde than many of its contemporaries; indeed, its narrative about the bad luck of a struggling Hollywood actor is the stuff of many a "backstage" melodrama from the major studios. Stylistically, though, this film is groundbreaking, which should come as no surprise when you learn a little about its makers.

Robert Florey, one of the film's two directors, came to be regarded as one of the most talented and unusual directors of B pictures. He worked with some of the most innovative image makers of his time, including the visionary directors

Josef von Sternberg and

Charlie Chaplin, as well as the all-important cinematographer

Karl Freund. Though he never achieved name-above-the-title renown, Florey earned a favorable reputation for unusual visual inventiveness in the realm of B pictures. He took his artist's eye to television in the 1950s and '60s, directing episodes of some of the era's most creative shows, including "The Twilight Zone" and its cousin, "The Outer Limits."

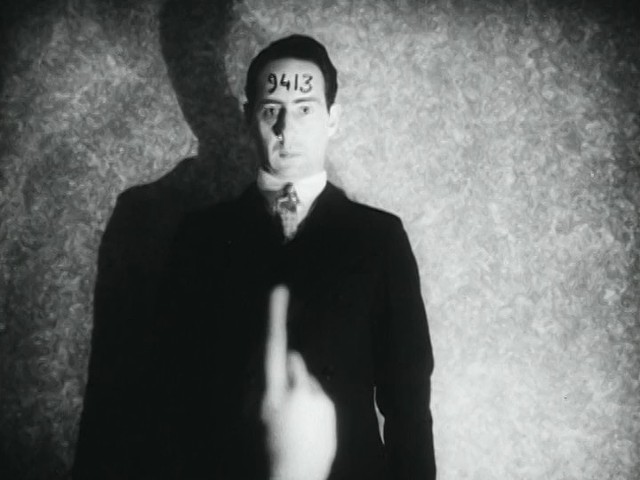

- Library of Congress

- One of the incredible silhouette shots from "The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra"

Slavko Vorkapich, whose name is remarkably fun to pronounce, is even more interesting. In the 1930s and '40s, he was sort of a hired-gun secret weapon for most of the major studios. His specialty was the now-reviled montage sequence, an enormously important narrative device that Vorkapich pioneered; he's still its one true master. Montage sequences are important to mainstream films because they condense often-complex narrative information into short, visually appealing scenes. No one did this better than Vorkapich, whose best-known (and most visually stunning) work was done for a couple of Frank Capra films,

Meet John Doe and

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. He made many others, as well, most of them in a kind of proto-psychedelic style that evokes kaleidoscopes and Surrealism. His work is well worth exploring; you can do so below.

Another creative contributor to "9413," equal in importance to Florey and Vorkapich, is credited for his "camera-work" in the film's opening credits as simply "gregg." This was none other than

Gregg Toland, who would, 13 years later, use every trick in the book — and then write a new book in the process — to shoot

Citizen Kane, among many other films. (Check out

Dead End and

The Grapes of Wrath for two of his other cinematographic masterpieces.) In 1928, Toland (like Florey and Vorkapich) had not yet made it into the upper echelons of studio filmmaking, and was, like his friends, an experimental soul who was entranced by the possibilities that cinema offered him.

What makes "9413" so interesting and unusual is its playfully experimental visual sense. Like the young, curious filmmakers they were, Florey and Vorkapich were unafraid to try any trick or gimmick. The result is that "9413" looks fresh and different and weird. The directors rejoice in the superimposition, the soft-focus shot, the

Dutch angle, the silhouette and the moving shadow. Most scenes feature stark or even blank backgrounds, thereby encouraging us to focus on the ludic camera trickery. "9413" is frenetic and joyous as it celebrates cinema's possibilities while it laments the harsh realities of the film industry. In that sense, it's a remarkably prescient film.

One further, and surprising, way in which "9413" is forward-thinking is its budget. The minuscule line-item budget for the film is cited often; far be it from me to break with tradition.

Negative ... $25.00

Store Props ... $3.00

Development and Printing ...$55.00

Transportation, etc. ... $14.00

Of that $97, the greatest part — $80 — went to the unavoidable costs of purchasing and developing film stock; the rest went to "incidentals." If that seems like a phenomenally low cost, it is — and was, even for 1928. Florey and Vorkapich used cardboard props and light sources that they had in their homes (i.e., table lamps), and they appear not to have paid their actors (who may well have participated in the project on a lark).

What's truly remarkable is not the tininess of the budget itself, but that the production of moving images has come back around to this kind of low-cost endeavor. The digital revolution has given us cheap or free storage for digital files, as well as the ubiquity of digital cameras and editing software (itself often cheap or free). The devices with which digital films may be made — smartphones, laptops, commercial-grade video cameras — are obviously not free, but they're such essential tools of the trade for modern image makers that their costs can quickly be amortized.

Digital filmmakers, get to it. The bar may be set pretty high, but you've got the time and the tools. I'm waiting for the modern equivalent of "9413."

- Library of Congress

- "The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra"