Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Monday, August 8, 2016

Election 2016 Closer Than Expected? GOP Voters to Decide Between Scott, Lisman

Posted By Terri Hallenbeck on Mon, Aug 8, 2016 at 8:15 PM

click to enlarge

The day before voters decide who should be the Republican Party’s candidate for governor, candidates Phil Scott and Bruce Lisman pushed to connect with as many voters as they could.

- Terri Hallenbeck

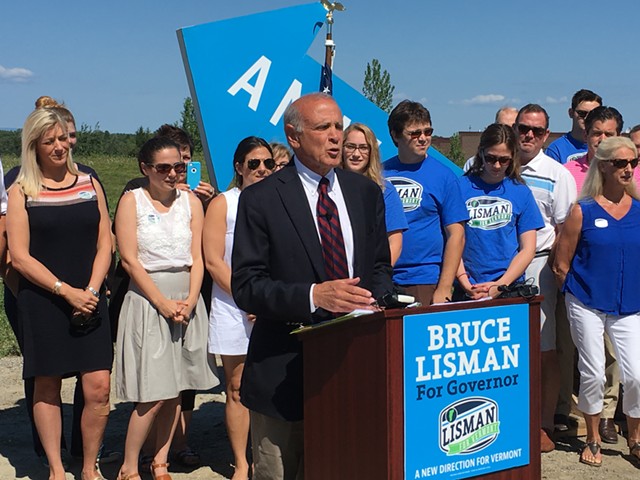

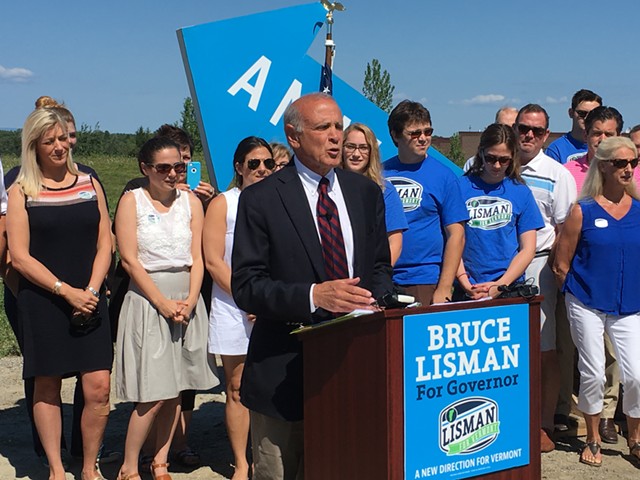

- Bruce Lisman speaks Monday at a press conference outside his Williston campaign office.

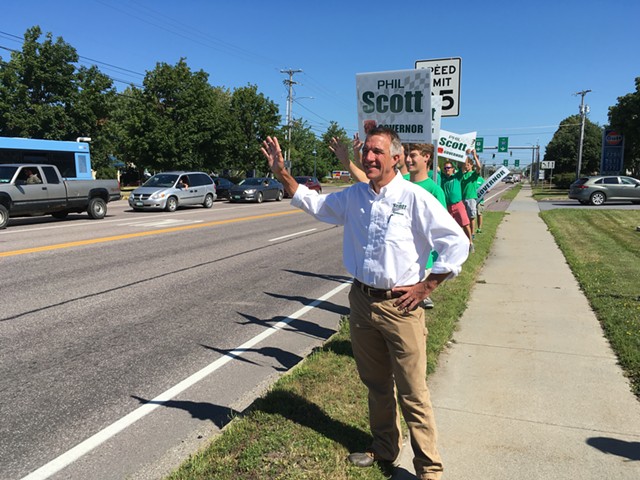

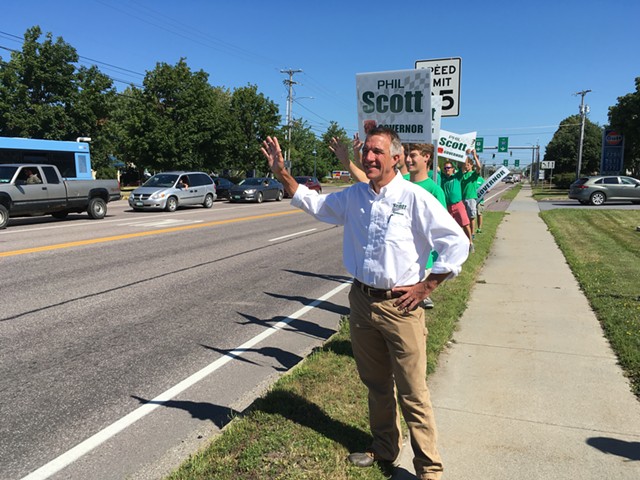

“We’re doing everything we can possibly think of to get people to understand how important this is,” Scott said Monday morning as he waved to passersby on Shelburne Road in South Burlington. “What we’re finding is that a lot of people think we have this sewn up, so their natural instinct is to think this doesn’t matter.”

“I think it’s going to be a close race,” said Lisman, flanked by 41 supporters outside his Williston campaign office during a Monday morning press conference.

Scott, 58, went into the campaign as the clear favorite. He’s the co-owner of an excavation company, has been lieutenant governor for six years, was a state senator for 10 years before that, and is a popular race-car driver. But Lisman, a 69-year-old retired Wall Street executive who has never held public office, has spent at least $1.6 million of his own money airing continuous television ads portraying Scott as a go-along insider.

Observers say the ad assault is having an impact and the race could end up being closer than many thought when Lisman entered the campaign with little name recognition.

“I think it’s narrowed,” said former Republican governor Jim Douglas, a Scott supporter.

“I’m getting a sense that the Republican race is going to be closer than people think,” said Mike Smith, a former aide to Douglas who now hosts a radio talk show on WDEV and is publicly neutral in the race.

Smith and Douglas both attributed the tightening to Lisman’s heavy advertising. “If you throw $2 million of negative ads against Mother Teresa and try to convince people she isn’t a saint, it’s going to have an impact,” Smith said.

click to enlarge

As with any campaign, much depends on the candidates’ ability to motivate their supporters to get to the polls. That’s especially challenging in a primary election, where voter turnout is traditionally low. Couple that with a new, early-August primary date and and many have bemoaned this year as even tougher. But Secretary of State Jim Condos said evidence shows that lively contested contests like this year’s draw the highest turnout, regardless of the voting date.

- Terri Hallenbeck

- Phil Scott waves to passersby on Shelburne Road in South Burlington on Monday.

The highest turnouts came in a mid-September 2000 primary and a late-August 2010 primary, when there were contested gubernatorial primaries, he said. Lower turnout occurred in interim September primaries when there were no high-level contests, Condos said.

Scott said Monday that he’s worried about turnout because many of his supporters are taking the race for granted, and also because the Democratic primary ballot has more races to lure voters — including a three-candidate contest for lieutenant governor. In Vermont’s open primary, a registered voter may choose any party’s ballot — Republican, Democratic or Progressive — but can submit only one.

Scott said some supporters have told him they already voted in the Democratic primary. “I’ve had numerous people tell me they’ve written me in on the other ballot,” he said. “It doesn’t do us a lot of good.” Those votes don’t count in the Republican primary.

Both Scott and Lisman did what candidates do on the eve of an election: expressed optimism.

Whatever their outward demeanor, the candidates themselves likely know better than anyone how they’re really doing. Smith said he believes both candidates in the Republican governor’s race are probably paying for daily tracking polls.

Candidates, however, routinely decline to reveal whether they are polling, which Scott and Lisman both did Monday.

Lisman said he based his conclusion that the race will be close on his own “sensitive data,” which he said came from campaign workers making more than 150,000 phone calls. “It’s tightened up,” he said of the race.

Douglas, who won a close first general-election race for governor in 2002, said daily tracking polls were a big help to him. While a Burlington Free Press poll that year showed Democrat Doug Racine up by 10 percent, Douglas’ own pollster told him it was a dead heat. Douglas won 45 to 42 percent.

In Douglas’ 2008 race against two challengers, Democrat Gaye Symington and independent Anthony Pollina, observers speculated Douglas might fail to exceed the 50 percent margin, which would put the decision in the hands of a Democratic-controlled legislature. But, Smith recounted, the campaign’s own polls showed otherwise. The campaign’s poll proved correct.

Not all the campaign talk Monday was about vote margins, however. Still lingering in the air were questions and accusations about who was behind a series of phone calls made to voters asking negative questions about Lisman. Lisman has insinuated it must have been Scott.

“Absolutely not,” Scott insisted.

Lisman’s campaign identified two Vermonters who received the calls, but direct evidence linking the calls to Scott was less clear than Lisman claimed. His campaign contended Monday that the two recipients had confirmed the calls were identified as coming from the Scott campaign. But in interviews with Seven Days, both recipients couldn’t make that definite connection.

Mary Richter of Northfield told Seven Days last week that she didn’t catch the caller’s identity. Chet Greenwood, the Orleans County Republican Committee chair, said Monday that the call to his house used the words “Phil Scott campaign,” but Greenwood said he couldn’t remember the exact wording. “It was either ‘paid for’ or ‘in support of’ the Phil Scott campaign,” he said. “I’m not going to say Phil had anything to do with it.”

Lisman, meanwhile, struggled to explain a $1,000 campaign contribution that he claimed he had returned. The money came from Richard Harriton, a former Wall Street colleague who was barred from working in the securities industry for defrauding investors.

Lisman said he returned the money when he saw how Harriton was characterized in news stories. Both Seven Days and VTDigger.org have mentioned the contribution. “I think it interfered with the campaign,” he said.

Asked why he solicited a contribution from Harriton in the first place, Lisman said, “I would probably ask anybody.”

There is, however, no indication in the state’s campaign finance filings that Lisman returned the contribution and his campaign has yet to prove it despite several days of questions from Seven Days.

Tags: Bruce Lisman, Phil Scott, Vermont Republican Party, gubernatorial campaign, election 2016, primary 2016, Image, Web Only

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

Since 2014, Seven Days has allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we’ve appreciated the suggestions and insights, the time has come to shut them down — at least temporarily.

While we champion free speech, facts are a matter of life and death during the coronavirus pandemic, and right now Seven Days is prioritizing the production of responsible journalism over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor. Or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

Related Stories

About The Author

Terri Hallenbeck

Bio:

Terri Hallenbeck was a Seven Days staff writer covering politics, the Legislature and state issues from 2014 to 2017.

Terri Hallenbeck was a Seven Days staff writer covering politics, the Legislature and state issues from 2014 to 2017.