On December 2, 1983, a band calling itself Blackwood Convention made it halfway through a semiformal dance at the University of Vermont’s Harris-Millis dormitory before they were jettisoned. Evidently uninspired by the group’s renditions of “Proud Mary” and “Scarlet Begonias,” dance organizers allegedly drowned out the band with a recording of “Thriller.”

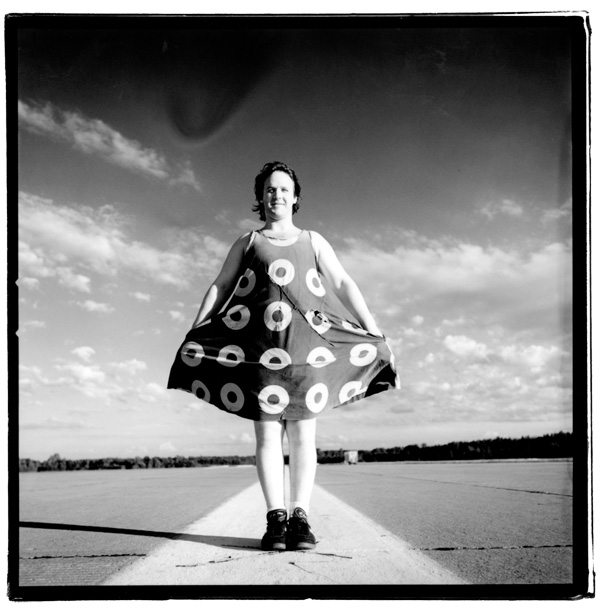

“Michael Jackson was being played constantly,” explains Amy Skelton, one of the few fans to attend the first performance of the band that would soon rechristen itself as Phish. “If you were a mainstream college kid listening to Michael Jackson, Phish is just not what you probably wanted to hear right now while you’re drinking your Miller Lite or whatever.”

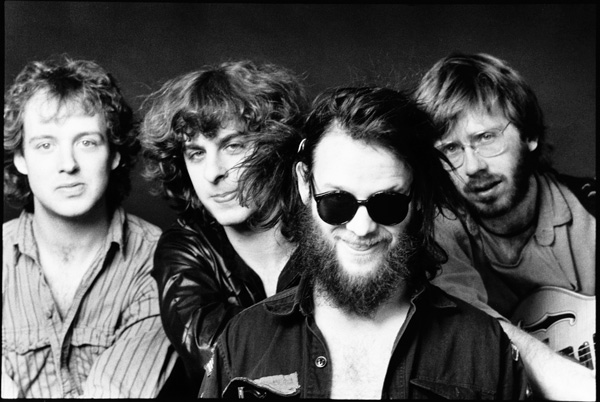

After a brief hiatus following Anastasio’s suspension from UVM and a couple of minor personnel changes, Phish crystallized around a four-man lineup when keyboardist Page McConnell joined Anastasio, Gordon and drummer Jon Fishman in 1985. Soon they were playing Burlington nightclubs Nectar’s and Hunt’s — and attracting more than just Skelton to their shows.

“The whole thing had a really great sense of humor, and it felt like you were going to your own personal little party,” she says. “I still think it feels like that.”

In an interview with the PBS NewsHour’s Jeffrey Brown this summer, Anastasio credited Vermont’s then-18-plus drinking age with creating an abundance of places to perform in Burlington.

“Every bar wanted a band,” he said. “We got really good at playing live. And I think if we weren’t in the right place at the right time, I don’t know that any of this would’ve happened.”

Page McConnell, Mike Gordon, Jon Fishman and Trey Anastasio in 1990 / Photo courtesy BC Kagan, © Phish

Page McConnell, Mike Gordon, Jon Fishman and Trey Anastasio in 1990 / Photo courtesy BC Kagan, © Phish

Nectar Rorris, who booked Phish on Sunday and Monday nights at his eponymous club, says the relationship was mutually beneficial.

“They were good to me. They played music young people like, and they were drawing young people in,” says Rorris, whose face graced the cover of the band’s 1992 album A Picture of Nectar. “When they started making a name out of state, there were more people coming in.”

But even as Phish began to build an audience, they “didn’t fit in” with Burlington’s music scene at the time, says Paul Languedoc. He served as the band’s soundman from 1986 through 2004 and still builds Anastasio’s guitars.

“They were the hippie band, whether that was deserved or not,” Languedoc says. “Everything at that time was new-wave kind of stuff and hardcore kind of music. The paper at the time, the Vanguard Press, sort of looked disdainfully at Phish. But they were popular. They drew big crowds.”

That dynamic continued into the early 1990s, Languedoc says, when Phish’s reach expanded well beyond New England.

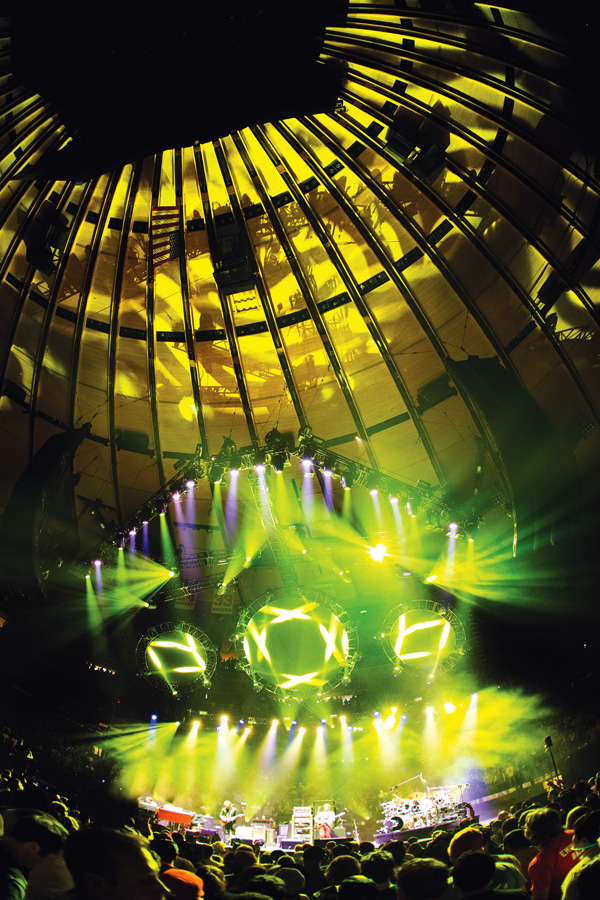

“We would go on tours and be playing in 1500- or 2000-seat theaters and then come back to Burlington and play a 400-capacity venue — the Front, primarily,” he says. “Nobody had any idea in Burlington that they were drawing big crowds in Georgia or Boulder.”

But for some aspiring musicians back home, Phish’s improbable ascent was nothing short of inspirational.

“As a fan, you felt you were part of the journey and owned some piece of the greater collective,” says Reid Genauer, who first saw the band at the Front (located in the present-day Skirack), soon after he matriculated at UVM in 1990. “I think it was because they were such a part of the fabric of Burlington as people and personalities and musicians — and just because they were authentic as a band.”

When Genauer founded Strangefolk the next year with fellow guitarist Jon Trafton, they found themselves emulating Phish’s rigorous practice regimen, their focus on the live show and eventually even their homegrown music festivals, which Phish had pioneered.

“It seemed like the only logical way forward was to do it the way they were doing it — and that’s what we did,” Genauer says.

That’s the sort of impact Mike Gordon — who, like McConnell and Fishman, still lives in Vermont — hopes Phish has had on his adopted state.

“The biggest compliment is when someone’s inspired,” the bassist says. “And if there’s a younger fan or musician that feels like, ‘Well, Phish had some success outside of Vermont, so we can, too.’”

Grace Potter, perhaps the biggest live act to come out of Vermont since Phish, says she still remembers seeing the band when it played at Sugarbush, near her Waitsfield home, in 1994.

“I was 10, and my parents said I was too young to go to the concert, but me and a couple friends hiked through the woods and listened. I was hooked,” she recalls.

As Potter was getting started, learning how to play Phish songs “was kind of a rite of passage,” she says. Now that she’s in the big league, Potter says she tries to follow Phish’s lead in connecting with her fans. And she, too, has taken to inviting local musicians to her festival, Grand Point North — including McConnell, who sat in with Potter and the Nocturnals for a ZZ Top cover last summer.

“As I’ve gotten to know them all better, all I can say is that they are brilliant and humble human beings with talent and compassion that reaches out in a lot of different directions and touches many people,” she says. “I’m so proud to share a little piece of Vermont’s musical legacy with those fine, fine gentlemen.”