Published August 27, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

Lou Del Bianco was just 6 years old in 1969 when his grandfather and namesake, Luigi Del Bianco, died at the age of 76. By then, the old man's lungs had literally turned to stone from accelerated silicosis, a consequence of years of inhaling rock dust while carving granite without a mask.

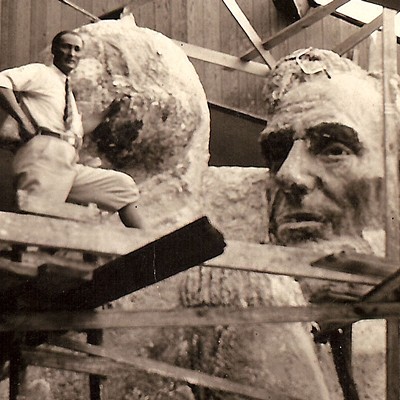

Today, Lou prominently displays a 50-pound white marble bust of his grandfather in the living room of his Port Chester, N.Y., home. Luigi Del Bianco, an Italian stonecutter from Barre who was classically trained as a sculptor in Austria and Italy, carved it himself in 1921, a year after returning to Vermont from World War I.

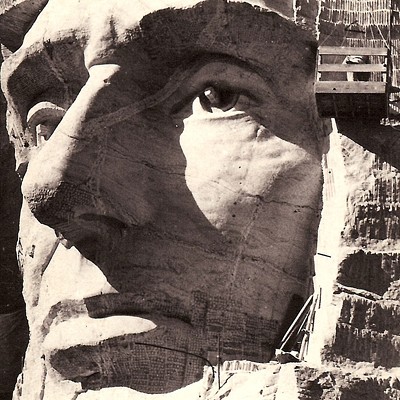

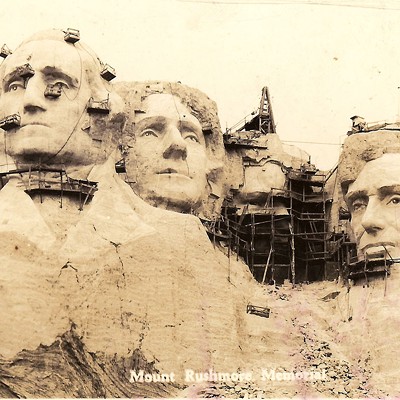

Lou Del Bianco is obviously proud of the cherished family heirloom. These days, however, he's far more interested in seeing his grandfather be recognized for the much larger busts he helped create — those on Mount Rushmore. Lou has long asserted that Luigi Del Bianco, who worked on the project from 1933 to 1940 and was appointed "chief carver" in 1935, was "the man who saved Jefferson's face and brought Lincoln's eyes to life."

Never heard of Luigi Del Bianco? You're not alone. Neither had Barre Mayor Thom Lauzon, one of the Granite City's most vocal boosters; or a research librarian at the Vermont Historical Society, which is located in Barre.

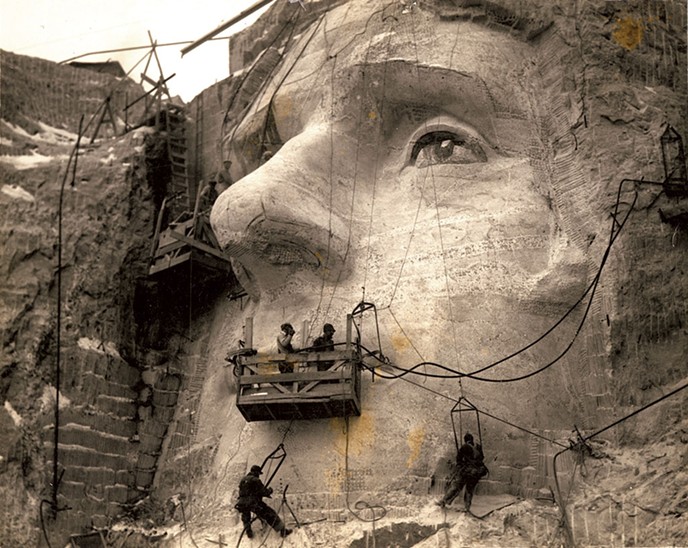

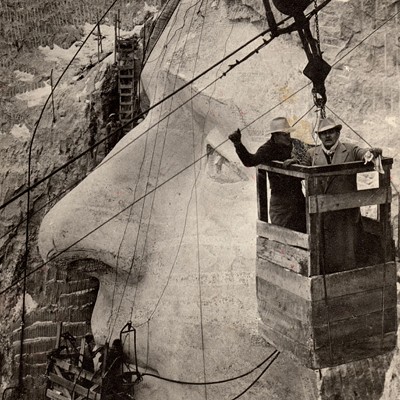

In fact, most tourists who visit the national monument in South Dakota's Black Hills never learn a thing about Del Bianco. His name is easy to miss on the museum's Workers Wall, where it's inscribed among those of the 400 mostly unskilled laborers who helped etch the likenesses of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln into the granite mountainside.

Instead, most visitors learn, via the museum's exhibits, website and literature sold in the bookstore, that Mount Rushmore was primarily the handiwork of Danish-American sculptor and engineer Gutzon Borglum and his son, Lincoln. Del Bianco's name and artistic contribution to that massive enterprise are virtually unacknowledged.

Lou Del Bianco, now 51, has tried for years to get the National Park Service to redress that slight and officially acknowledge his grandfather's significance as Borglum's right-hand man. To date, those efforts have been largely unsuccessful.

But that could change soon. A new book by Albany, N.Y., author Douglas Gladstone, titled Carving a Niche for Himself: The Untold Story of Luigi Del Bianco and Mount Rushmore, sheds light on this mostly forgotten figure from Vermont's past. The book traces Del Bianco's life as a master sculptor and stoneworker, and the efforts by his family years after his death to document his crucial role in creating one of America's most iconic landmarks.

Since its publication in April, Gladstone's book has captured the attention of historians as well as state and national lawmakers. U.S. Rep. Pat Tiberi, a Republican from Ohio's 12th congressional district and cochairman of the Italian American congressional delegation, read Gladstone's book recently and said that Del Bianco "should be formally recognized" for his work on the national memorial.

Similarly, State Sen. George Latimer, a Democrat from New York's 37th senate district, issued a press release in April after the book was published, calling on the U.S. Department of the Interior to formally recognize Del Bianco "for his service to the nation."

Gladstone himself only learned of Luigi Del Bianco when he heard Lou and Lou's Aunt Gloria, Luigi Del Bianco's sole surviving child, interviewed in October 2011 for a National Public Radio "StoryCorps" piece. In it, Lou recounted the day in second grade when his mother casually mentioned to him, "Grandpa carved Lincoln's eyes."

"Thus began my 40-plus-year odyssey to find out what he did," Lou tells Seven Days in a phone interview. Both Lou and his now-deceased Uncle Caesar, Luigi's son, worked together in the late 1980s and early '90s searching Library of Congress archives for primary-source material proving Del Bianco's integral involvement in the project. Many of the documents they discovered, including notes and letters written by Borglum himself, are now available on Lou's website, luigimountrushmore.com, and are included in Gladstone's book.

Luigi Del Bianco was born aboard a ship near Le Havre, France, on May 8, 1892, and grew up in Meduno, a small town in northeastern Italy. Recognized early on for his artistic ability, Del Bianco was sent to Vienna, Austria, at the age of 11 to train as a sculptor. When he was 17, Del Bianco immigrated to Vermont at the invitation of cousins who worked in Barre's granite sheds. At the time, Gladstone notes, the city's thriving granite industry accounted for as much as 30 percent of the nation's total granite production.

City directories and other historical documents from that era confirm that Del Bianco lived until 1915 in Barre, where he worked for the Giudici Brothers and the World Granite companies. That year, he returned to Italy to fight in World War I, then came back to Vermont in 1920 before later relocating to Port Chester.

Neither Gladstone nor Lou Del Bianco knows much else about Luigi's time in Barre, nor have they found any surviving relatives in Vermont. They do know that he lived in two different Barre boardinghouses: one at 10 Sixth Street, which is now a single-family home, and another at 565 North Main Street, which has since been demolished.

If Del Bianco carved anything noteworthy in Barre, they have yet to find it. That's not surprising, Lou says, as most of his grandfather's stonework in those years likely would have been headstones and other cemetery monuments that were rarely signed by the artist. Lou has confirmed that his ancestor carved about 500 monuments in Port Chester cemeteries.

But if Luigi Del Bianco didn't leave behind identifiable works in Barre, the city left an indelible mark on his life and career, says his grandson. It was in Barre, in 1920, that Del Bianco met fellow carver Alfonso Scafa, who hailed from Port Chester. The New York town is just 15 minutes away from Stamford, Conn., where Scafa worked in Borglum's studio. According to Lou, Scafa immediately recognized Del Bianco's skill and introduced him to Borglum. Del Bianco's association with Scafa and Borglum was set in stone when Scafa introduced Del Bianco to his sister-in-law, Nicoletta Cardarelli, whom Del Bianco later married.

"If my grandfather hadn't gone back to Barre, I don't think he would have met Gutzon Borglum, and I don't think he would have been chief carver of Mount Rushmore," Lou concludes. "So he owes a lot to Barre."

Mount Rushmore wasn't the only large monument on which Del Bianco and Borglum worked together. Earlier in their careers, Borglum invited Del Bianco to assist him in sculpting Stone Mountain in Georgia, which depicts Confederate States' President Jefferson Davis and generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee. Borglum later quit that project owing to friction with its backers.

Both Lou and Gladstone assert that Del Bianco's importance to the creation of Mount Rushmore is undeniable. Notably, in a June 3, 1933, handwritten letter sent to John Boland, chairman of the National Memorial Commission, Borglum remarks that "we could double our progress if we had two like Bianco," the name he often used when referring to Del Bianco.

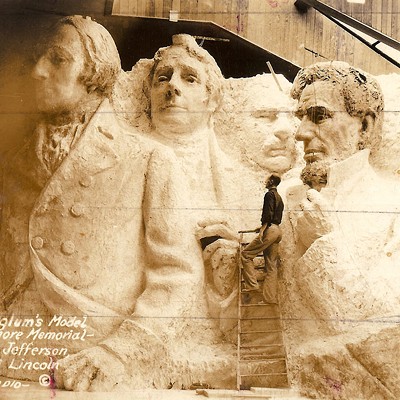

Of even greater significance is a July 30, 1935, letter from Borglum in which he referred to Del Bianco as his "chief carver," who had replaced another Italian stonecutter, Hugo Villa, two years earlier. Del Bianco's first assignment, as Gladstone explains, was to dynamite Villa's first attempt at Jefferson's face off the side of the mountain and start fresh in a new location. Clearly, Borglum was impressed by Del Bianco's sculpting abilities, describing him in a 1936 letter as "the only intelligent, efficient stone carver on the work who understands the language of the sculptor."

Today, though the National Park Service doesn't deny Del Bianco's contributions, it downplays his significance. In a statement to Seven Days — worded identically to the one provided to Gladstone for his book — Maureen McGee-Ballinger, chief of interpretation and education at Mount Rushmore National Memorial, writes:

"Luigi Del Bianco was one of the skilled carvers that traveled from the East to work on the sculpture. Carving on the sculpture began in October of 1927 and was completed in October of 1941. According to our check ledgers, time-cards and payroll records, Mr. Del Bianco worked on the sculpture in 1933, 1935, 1936 and 1940." McGee-Ballinger goes on to describe Del Bianco as a "skilled craftsman" who is "recognized for his contributions to the sculpture both in our museum and on our Worker Wall."

Follow-up questions seeking to clarify the National Park Service's position on Del Bianco's role went unanswered as of press time.

For his part, Lou Del Bianco is frustrated that his grandfather's contributions are lumped together with those of the tram operators and unskilled miners who hauled rubble off the mountain. As he points out, no one on the project but Borglum himself was paid more than Del Bianco, whose salary Borglum often paid out of his own pocket.

Furthermore, on two occasions when Del Bianco quit the project — largely due to harassment, petty bickering over his wages, and other abuses that both Lou and Gladstone attribute to anti-Italian bigotry of the era — work on Mount Rushmore ground to a halt.

"If the tram operator had quit," Lou says, "I don't think it would have had the same effect."

For the past 27 years, Lou Del Bianco has worked as a professional actor, singer and storyteller. In recent years he's performed, among other things, a one-man show that "brings my grandfather to life." He even performed it at Mount Rushmore at the park's invitation. More recently, he was invited to stage that show in Vermont this fall, as part of a celebration of the state's granite industry.

Upon his return to Vermont, Lou Del Bianco may find a powerful ally for his cause. Although Sen. Patrick Leahy declined to weigh in on the controversy surrounding Del Bianco's official recognition by the National Park Service, in a written statement provided to Seven Days last week, he hinted at Del Bianco's historical importance:

"Both of my grandfathers were stone carvers here in Vermont, and it makes me proud to know that several chapters of American history are etched in Vermont stone," the senator writes. "Every time I cross the Supreme Court's threshold, I remark to anyone listening that its white façade is etched in Vermont marble. So are the columns of the Jefferson Memorial. Even iconic Mount Rushmore bears the timeless mark of Vermont craftsmanship ... It's a legacy well worth remembering, valuing and preserving."

Gladstone says that he wrote the book about Luigi Del Bianco in part because it's a compelling tale, but also because it's time to right this "historic wrong," he says.

"If this story isn't the realization of the American Dream for an immigrant," Gladstone adds, "I don't know what is."

INFO

Carving a Niche for Himself: The Untold Story of Luigi Del Bianco and Mount Rushmore, by Douglas Gladstone, Bordighera Press, 132 pages. $12.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Taken for Granite"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer

Apr 22, 2024 -

At Studio Place Arts in Barre, a Group Exhibit Highlights Embroidery

Apr 10, 2024 -

Sculptor Clark Derbes Gives New Life to Fallen Wood

Jan 10, 2024 -

Backstory: July Flood Hit 'Closest to Home' for Barre-Raised Reporter Courtney Lamdin

Dec 27, 2023 -

Volunteers Create Quilts for Residents at Barre-Area Homeless Shelters

Nov 1, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.