Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Christopher Kaufman Ilstrup Redefines Vermont Humanities in Turbulent Times

Published April 1, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated April 8, 2020 at 10:09 a.m.

During the Cold War arms race, when the U.S. government was funneling money into scientific and technological research, the public intellectuals who called themselves "academic humanists" — university lecturers, deep readers of classical texts, and other cultural ruminants — began to feel neglected. In 1964, a panel of concerned scholars presented a report to Congress to plead their case for a federally subsidized humanities agency.

Their proposal, which led, a year later, to the establishment of the National Endowment for the Humanities, asserted that it was in the country's best interests to "correct the view of those who see America as a nation interested only in the material aspects of life and Americans as a people skilled only in gadgeteering."

Among the side effects of this profligate gadgeteering, the report noted, was the dubious luxury of convenience, the sudden abundance of formless hours: "'What shall I do with my spare time' all-too-quickly becomes the question 'Who am I? What shall I make of my life?'... The humanities are the immemorial answer to man's questioning and to his need for self-expression; they are uniquely equipped to fill 'the abyss of leisure.'"

In the midst of a global pandemic that has dismantled the structures of daily life, the question of how to fill that abyss feels particularly urgent. Christopher Kaufman Ilstrup, executive director of Vermont Humanities, believes that when we find ourselves grasping for a frame of reference, the stories we tend to overlook can be just as revealing as the ones we choose.

"I've been noticing a lot of references to the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which is an important moment to look back on," he said. "But for gay men, in particular, we look back to the AIDS crisis, when the government was ignoring the pandemic and actually making it worse. What can we learn from that? What are the things we should be calling out now about how the government is responding to this need?"

Kaufman Ilstrup, now in his second year as executive director, tends to see the political implications of every narrative. If the purpose of the humanities — literature, philosophy and history — is, as he puts it, to tell the "human story," the human story of Vermont has been riddled with omissions. "The story we tell about ourselves is all about cows and maple syrup and skiing and white people," he said. "It was probably never a true story, and it's certainly not a true story now."

Kaufman Ilstrup, 50, has an ageless, impish aura. He has several tattoos on his right arm, a literary tableau-in-progress: On the inside of his forearm is Mr. Tumnus from The Chronicles of Narnia, standing under a street lamp with his signature creepy umbrella. Adjacent to Mr. Tumnus is Yorick's skull, from Hamlet, nestled in a bed of Shakespearean flora — "woodbine, wild roses, love-in-idleness," Kaufman Ilstrup recited, like a docent at a botanical garden.

Over the past few years, Vermont Humanities has undergone a subtle rebrand, partially manifested in its decision to drop the word "Council" from its logo. "It has this pretty elitist connotation that we're the experts, when, in fact, we're all experts in telling our own stories," Kaufman Ilstrup said.

But the shift goes beyond optics. When Kaufman Ilstrup's predecessor, Peter Gilbert, announced his retirement, the board wanted to find someone who would broaden the organization's approach to disseminating scholarship.

"We needed to up our game in terms of diversity and access and inclusion," said Katy Smith Abbott, chair of the Vermont Humanities board. "It felt like a responsibility — not that Peter didn't have that goal, but we needed to look at what that means in the second decade of the 2000s, in a state that's overwhelmingly white."

Kaufman Ilstrup, for his part, wants to "re-center the narrative" — to foreground the voices of marginalized communities. "I think Peter really cared about unheard voices, but now, we're stating it out loud," he said. "We want to be part of the solution, especially at a time when there's so much racism and xenophobia."

Vermont Humanities isn't alone in recasting its mission as a cultural organization; according to Kaufman Ilstrup, state councils across the country are grappling with their duty, as conduits of public discourse, to examine their canonical biases and address themselves to a new generation of minds.

"Even five years ago, most humanities councils would have said that our job is to present scholarly research to the public and to make sure we're finding scholars who can talk to regular people — sort of in a condescending fashion, what we jokingly call 'the sage on the stage model,'" he said. "And there's a lot of great scholarship that should be shared. But we also strongly believe that we should be telling communities' stories, as well, and that there are lots of different ways to be an expert on an issue."

Turning the Page

There are 56 humanities councils throughout the U.S. and its territories, which receive federal dollars through the National Endowment for the Humanities. Roughly half of Vermont Humanities' approximately $1.5 million annual budget comes from the NEH, a contribution that has held steady over the past few years, despite President Donald Trump's repeated threats to defund cultural agencies.

Vermont Humanities is headquartered in a rambling 19th-century Victorian — "our 'Addams Family' home," as Kaufman Ilstrup fondly calls it — a few blocks off Main Street in Montpelier. From his office window, Kaufman Ilstrup used to be able to peer into the playground of Union Elementary School and see his son, Jacob, now 11, running around during recess.

Kaufman Ilstrup's favorite room is the basement, which houses thousands of books for the reading groups that the agency coordinates around the state. On a drizzly Friday morning in mid-March, a long tongue of water had snaked its way across the floor, a somewhat chronic situation in a 200-year-old structure. The books, aerated by dehumidifiers and kept off the ground on large, utilitarian shelves, stayed dry.

As many as 80 reading groups are active at any given time, with themes that range from "B.I.G. (Big, Intense, Good)" to "Border Crossings," a series on the immigrant experience in America. Recently, Kaufman Ilstrup saw a Facebook comment from someone who said they were interested in science fiction by writers of color, so he responded directly to them: "I can help you with that!" (He said, somewhat giddily, "I don't think they think I'm serious!")

Kaufman Ilstrup became visibly bouncier when he descended the basement stairs. He introduced each stack of books as if they were guests at his party: "Here we are, with Henry James, Jane Austen, and there's Victor Hugo ... oh, and there's Christopher Isherwood — I'm a particular fan of Christopher Isherwood." He lingered over another shelf, pushing up his glasses. "Oh, here's a great book, Nickel and Dimed, about living on minimum wage."

The distribution and mulling over of books accounts for much of Vermont Humanities' public activity, particularly its Vermont Reads program, a statewide initiative to engage students in a work of literature. The agency's other major function is providing grants; each year, it distributes some $50,000 to cultural organizations throughout the state.

In 2019, Vermont Humanities funded a workshop on Shakespeare for war veterans at Norwich University, a walking tour of New American food markets in Burlington's Old North End, and a summer camp at the Old Stone House Museum in Brownington, which taught grade schoolers about first contact between white settlers and the Abenaki.

The spread of the coronavirus has canceled practically every plan in America, and all Vermont Humanities programming is on hold at least through the middle of May. In a non-pandemic year, Vermont Humanities organizes some 800 free public events, including First Wednesdays, a monthly lecture series held at libraries from Brattleboro to Newport. A sampling of talk titles from the 2019-20 season: "Edward Gorey's Morbid Nonsense," "The History and Structure of Stone Walls," "The Salt of the Earth: The Rhetoric of White Supremacy" and "The Poetics of Protest in Nina Simone's 'Mississippi Goddam!'"

Over the past few weeks, Kaufman Ilstrup and his staff have been scrambling to adapt to an exclusively virtual reality. Poet Richard Blanco, who was scheduled to speak at the Unitarian Church of Montpelier on April 3, has agreed to livestream his talk; First Wednesdays lectures will also move online for the rest of the month. In this time of extreme social isolation, said Kaufman Ilstrup, people need community more than ever, and the spaces where community thrives, especially in rural areas, are particularly vulnerable to the economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis.

As policy makers deliberated over an emergency stimulus bill last month, humanities organizations lobbied for $500 million in relief for the NEH to help sustain museums, libraries, historical societies and other cultural cornerstones. The final bill, approved by the Senate on March 25, allocated just $75 million.

"Right now, our economy is shutting down, and that is hitting culture workers very, very hard," said Kaufman Ilstrup. "And it's important, as we think about how to reboot our economy, to think about how cultural and creative workers are valued. All of us are among the frontline folks to get laid off."

People need language to make sense of a suddenly shattered world. Humanities Washington has started to post pandemic-adjacent prompts on its website, a way of encouraging people to grapple with philosophical and ethical questions in a time of crisis. Kaufman Ilstrup said that he and his staff are considering a similar approach.

Recently, the executive director of Utah Humanities sent him Lynn Ungar's "Pandemic," a poem about the sacredness of hunkering down that has been circulating around the internet as a sort of psalm of the times. An excerpt: "Do not reach out your hands. / Reach out your heart. / Reach out your words. / Reach out all the tendrils / of compassion that move, invisibly, / where we cannot touch."

"I think it really resonates with people right now, to just sit quietly with those words and think about them," Kaufman Ilstrup said. "That's what the humanities can do — they can take us out of this spin cycle."

Standing Up

Christopher Kaufman Ilstrup has a very precise name, which, in print, must always be written out in its entirety on first reference. Upon subsequent mention, he insists on being called Kaufman Ilstrup, lest he be confused with his husband, whose name, amazingly, is Christopher Ilstrup, except he goes by Chris. But long before they met, Kaufman Ilstrup declined to abridge himself: "'Chris' just wasn't my preference," he explained in his delicate way.

Kaufman Ilstrup grew up in Vergennes, across the street from the Bixby Memorial Free Library. If he were a comic book superhero, his origin story would begin the day he was allowed to walk to the library by himself for the first time. He was 7 or 8 years old, a small, bespectacled nerd, passing through the marble Ionic columns of the lobby into a vast realm of knowledge that smelled of dust and glue. There, he chanced upon a quiet corner, where a shelf of single-play Shakespeare editions awaited him. ("In my memory, I read all of them, but I'm sure that's not true," he said.)

Over the course of his childhood and adolescence, Kaufman Ilstrup spent hundreds of hours in the Bixby, metabolizing all the Shakespeare he could find. After graduating from Vergennes Union High School, he went to Kenyon College in Ohio, where he majored in dance and drama and minored in history. He came back to Vermont briefly, for a job as a canvass director for Vermont Public Interest Research Group, before going to the London School of Economics and Political Science for his master's in international development.

"I'm not one of those people who complains about young people leaving Vermont," said Kaufman Ilstrup. "I think they should leave. They should go out there and experience the world, and many of us will come back. And when we come back, we're stronger for it, because we've had much more diverse experiences."

When Kaufman Ilstrup finally returned to Vermont for good, in the late '90s, he went back to the nonprofit world — first to Rural Vermont, where he worked with farmers in the early days of the local food movement, then to Outright Vermont, a resource center for queer youth.

Around that time, he and his wife of three years, whom he'd met at Kenyon, were in the midst of separating; Kaufman Ilstrup, who identified as bisexual during their marriage, began to more fully explore his queer identity. (He and his ex, who now lives in San Francisco, have remained close; they keep in touch via FaceTime, and Kaufman Ilstrup and his family spend a week every summer with his former sister-in-law and her kids.)

Soon after he moved back to Vermont, Kaufman Ilstrup became involved with the Radical Faeries, a queer men's spirituality movement that combines neo-pagan rituals and back-to-the-land environmentalism with theater and drag. At Faerie Camp Destiny, a 166-acre retreat in Grafton established by members of the group, Kaufman Ilstrup directed a production of A Midsummer Night's Dream.

"Christopher was comfortable with the A-gays, and he was also comfortable hanging with the Faeries, running around naked in the North Country," said Khristian Kemp-Delisser, who worked under Kaufman Ilstrup for a year when he was the executive director of R.U.1.2?, now the Pride Center of Vermont. "We'd have these house parties where, at some point, you'd have to ask people for money, and he was a master at it — knowing how late in the night to go, how drunk people have to be. He's funny, disarming and charming. It's hard not to like him."

But that chameleon quality, said Kemp-Delisser, doesn't extend to his principles. When they worked together in the early 2000s at R.U.1.2?, same-sex marriage had just become legal in Vermont, and the word "queer" was at least a decade away from shedding its negative connotations. In spite of that lack of widespread acceptance, Kaufman Ilstrup insisted on calling R.U.1.2? a "queer" community center, because he believed the term was more inclusive of all identities.

"People would call us and say, 'Do you know you have 'queer' in your name?'" recalled Kemp-Delisser. "He coached me in not being apologetic about where we stand."

A Learning Moment

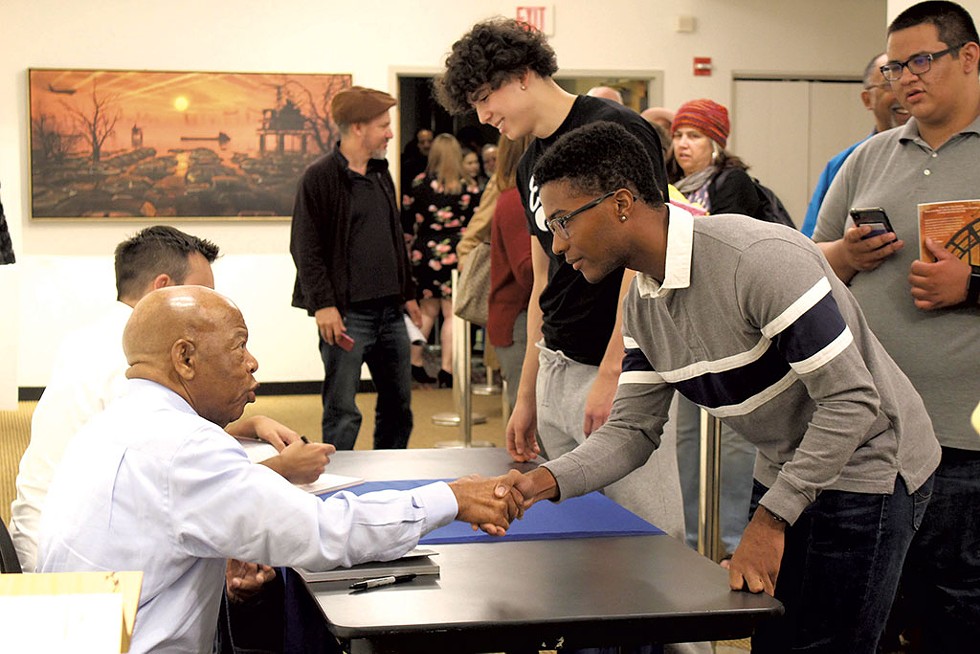

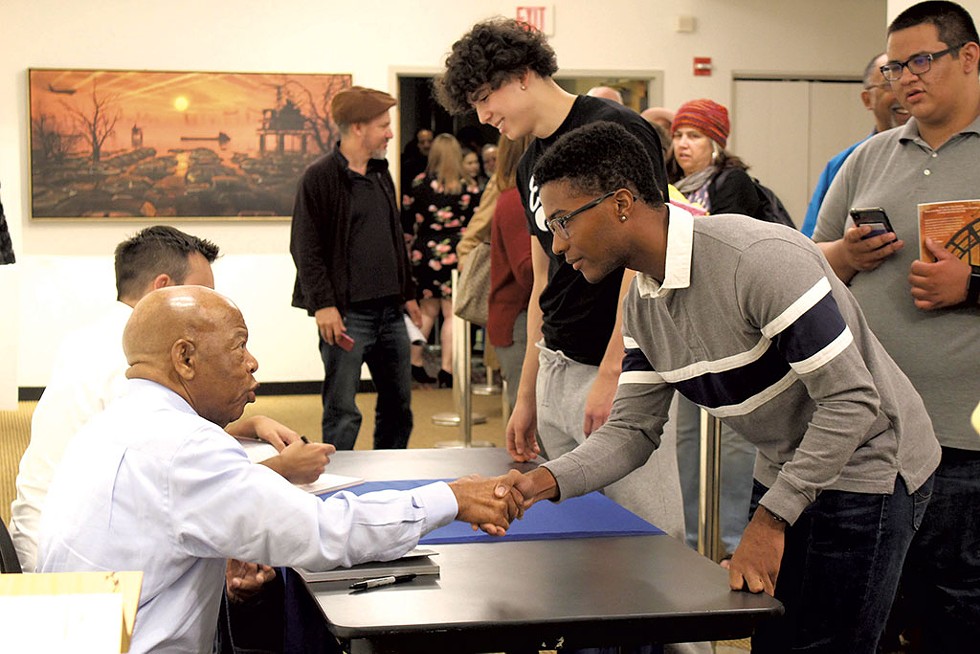

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Vermont Humanities

- John Lewis signing books at the Flynn on October 7, 2019

In 2018, under the leadership of Peter Gilbert, Vermont Humanities selected March: Book One for its 2019 Vermont Reads program. The graphic memoir, the opener in a trilogy about the life of congressman and civil rights champion John Lewis, was the first comic book in the 18-year history of Vermont Reads. As Kaufman Ilstrup put it, one of Gilbert's parting messages to him was something along the lines of: "'Here, this book is going to be hard! Do this!'"

"They thought it was going to be hard because it was the first graphic novel we'd chosen," said Kaufman Ilstrup. "They felt like the challenge would be getting people to take it seriously, but there was very little pushback on it in the end." (In fact, the March series is the second most widely taught comic in the public school system, after Art Spiegelman's Maus trilogy.) What turned out to be more complicated ("and interesting and exciting"), Kaufman Ilstrup said, was the book's content: "It promoted conversations about racism, about nonviolence, about how we are complicit in the ongoing white supremacist system that still needs to be addressed."

When it was time to pick the book for Vermont Reads 2020, Kaufman Ilstrup wanted to tighten the focus on systemic racism. Among the 10 or 15 possible titles suggested by librarians from around the state, Vermont Humanities chose The Hate U Give, the best-selling 2017 young adult novel by Angie Thomas. The book, which was adapted into a movie, tells the story of Starr, a black teenage girl navigating the disconnect between her white prep school and her black neighborhood. In the novel's pivotal scene, Starr watches from the passenger seat when a police officer fatally shoots her best friend, a young, unarmed black man, during a traffic stop.

After choosing the book, Kaufman Ilstrup sought feedback from the Vermont State Police, the Attorney General's Office and others. He said that the response was generally — though not universally — positive, and that most of the concerns came from leaders of color.

One of those leaders was Lydia Clemmons Jr., who oversees programming at Clemmons Family Farm, a black-owned farm and nonprofit in Charlotte that supports African and African American artists. Over the past three years, she has received grants from Vermont Humanities to host speakers; in 2019, the farm held an arts workshop for elementary and middle schoolers based on March: Book One. But Clemmons said that Vermont educators, many of whom teach in classrooms with few, if any, students of color, aren't prepared to tackle the realities of The Hate U Give — police brutality, drugs, the racial complexities of an urban environment.

"I grew up here, and my son grew up here — we know what it's like to be the only black kid in the room," she said. "I appreciate that Vermont Humanities is trying to be contemporary and relevant, but there'd be so much work to do to make sure people don't slide into thinking that all black people are into drugs and living in the ghetto. Those are important realities of life for black people in this country, but those aren't necessarily the issues for the black community in Vermont."

Based on Clemmons' feedback, Kaufman Ilstrup organized an anti-racism training in February, led by Laura Jiménez, a lecturer at Boston University. During the workshop, Jiménez debriefed a room full of largely white, middle-aged teachers and librarians on the cultural significance of Tupac Shakur — The Hate U Give is a reference to the late rapper's THUG LIFE tattoo, an acronym "The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody" — and the distinction between East and West Coast rap.

"If we don't know that music, we'll miss a lot," said Kaufman Ilstrup. "That's a pretty big ask of a group of 50-year-old librarians from Vermont."

Kaufman Ilstrup agrees that there might be some danger in pursuing The Hate U Give. "This is a very important learning moment for us," he said. "I think it's our job, as a cultural organization, to push people beyond their comfort zones. But we do have concerns. If there's a classroom of 30 white kids and one African American student, that kid might get targeted, or asked to represent, or assumed to have had the same experience as Starr, when, in fact, most black kids in Vermont haven't had those experiences."

Katy Smith Abbott, the Vermont Humanities board chair, acknowledged that she initially had reservations about choosing the book. "This was one of those times when we could have said, 'It's too hard; it's not safe; let's not do it,'" she said. "But this also feels like who we want to be as an organization, and it's not because we want to look good. I think Christopher is really courageous. If this work is going to resonate and matter, we're going to have to be OK with fumbling."

In a state where 92 percent of the population is white, communities of color tend to be both overlooked and hyper-visible. Since 2015, hate crimes have risen sixfold in Vermont, according to data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation; in 2018 alone, 30 out of 45 reported incidents cited race as a motivating factor.

"The humanities are about facilitating conversations about the discourse of power," said former board member Ben Doyle, who chaired the search committee that brought on Kaufman Ilstrup. "Christopher wears his heart on his sleeve, but his mind is there, too. He speaks, literally and figuratively, with a soft voice. In these times, that's the kind of person you need to facilitate those conversations."

Complicating this dynamic is the fact that the cultural institutions that often seek to facilitate those conversations, in Vermont and across the country, are overwhelmingly white: A 2018 survey of New York City's cultural sector, commissioned by Mayor Bill de Blasio, found that white people made up two-thirds of those in leadership positions in the region's museums, libraries and historical societies.

Eight of the nine Vermont Humanities staff members are white; this year, Beverly Colston, director of the University of Vermont's Mosaic Center for Students of Color, became the board's only nonwhite member. Kaufman Ilstrup said that bringing in more people of color is a high priority, but, as in all situations involving entrenched systems of inequality, progress is slow — and the people he might otherwise tap for leadership roles tend to be busy advocating for their own communities."I know from working in the LGBTQ movement that it's hard to feel like your message is being overtaken by a group that doesn't really get you," he said. "That's why telling my story is so important. I very much appear to be a cisgendered white man, and that is not my whole story. I am a person who grew up in a small town, in a working-class family. I am a person who is very queer-identified and doesn't necessarily identify as cisgendered. And I have a long history of working in these movements — in the queer movement, the anti-racism movement — but most people wouldn't look at me and say that."

And yet, he realizes, he can't simply use his story to earn people's trust. "That's why showing up is so important — building a relationship, being part of the conversation, knowing when not to talk," he said. "You have to be able to give up your seat and put somebody else there."

Learn more about Vermont Humanities and its upcoming online programming at vermonthumanities.org.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Oh, the Humanities | Christopher Kaufman Ilstrup redefines a cultural agency in turbulent times"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Chelsea Edgar

Bio:

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

More By This Author

Latest in Culture

Related Locations

-

Vermont Humanities

- 11 Loomis St., Montpelier Barre/Montpelier VT 05602

- 44.26046;-72.57067

-

802-262-2626

802-262-2626

- www.vermonthumanities.org

find, follow, fan us: