Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center…

-

Health Care

The $200 Mystery: Anonymous Person Mails Cash…

-

News

Ethics Panel Dismisses Complaint Against Ram Hinsdale

- Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse 0

- Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education 0

- Recent Catastrophes Prompt New Thinking About Ways to Manage Vermont's Flood-Prone Landscape Environment 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

-

Politics

Federal Hemp Regulations Trip Up Vermont Growers

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

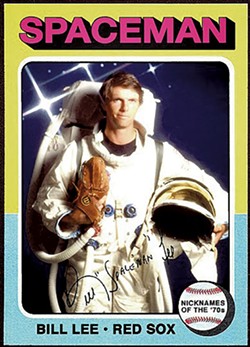

On the Field With Bill Lee, Red Sox Legend and Vermont Gubernatorial Candidate

Published August 17, 2016 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 25, 2022 at 7:07 p.m.

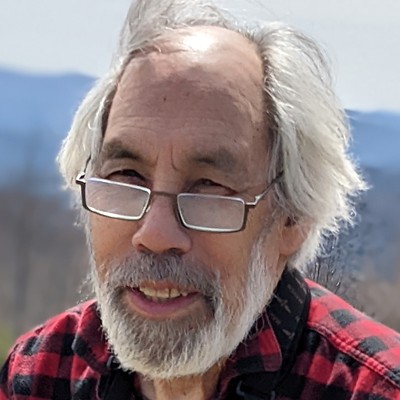

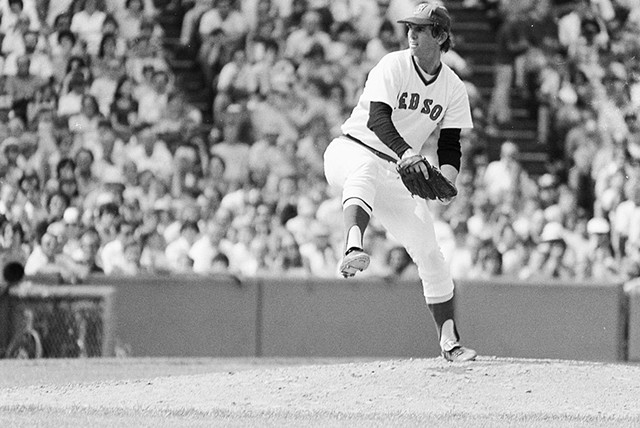

Bill Lee stands on the mound rolling a ball over in his hand as he stares at Fenway's home plate. Beyond him, in left field, an American flag waves atop the Green Monster against steely, late-summer clouds. The left-handed pitcher digs his cleat into the dirt and, as he begins his windup, grins at the young hitter anxiously shifting his feet in the batter's box.

The Spaceman, as his Boston Red Sox teammate John Kennedy nicknamed him long ago, unleashes a hellacious pitch that seems to fly as high as the iconic Citgo sign beyond the left-field wall. It's a slow, arching moonshot of a thing that scrapes the sky before plummeting back to Earth and past the batter, who swings too hard and too early, corkscrewing into the ground. It's the eephus pitch — or, as the lollipop curveball has become known in Boston lore, the Leephus or Space Ball. The crowd erupts.

On the next pitch, the batter gets his revenge, squeaking a grounder just past the mound for a single. It wasn't quite the curveball Lee hung to the Cincinnati Reds' Tony Pérez, who promptly deposited it over the Monster in game seven of the 1975 World Series. But it was a mistake. Irked, Lee snaps his hand at the ball when it's thrown to him. He cools off and strikes out the next batter to retire the side.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Bill Lee hits a homer.

When Lee returns to the dugout, someone asks, "Bill, did you really just throw that kid an eephus?"

"Yeah, I threw him an eephus," Lee grumbles. Then, winking, "I shoulda put it in his ear."

Bill Lee plays to win. Even at almost 70 years old. Even at Wiffle ball.

This Fenway Park is not the famed home of the Red Sox, where Lee pitched in the late 1960s and '70s. It's Little Fenway, one of three Wiffle-ball-scale replicas on Pat O'Connor's land in Essex Junction. (The others are miniaturized versions of Chicago's Wrigley Field and Kevin Costner's cornfield diamond from Field of Dreams.) Lee hasn't pitched for Boston since 1978 — or in the big leagues since he was kicked off the Montréal Expos in May 1982. Today, he's one of the local notables in the Celebrities-Sponsors Game that kicks off the 15th annual Travis Roy Foundation Wiffle Ball Tournament.

And that "kid" at the plate is, in fact, a kid. He stands an Eddie Gaedel-like three and a half feet tall and is maybe 6 years old. But he just singled off a member of the Red Sox Hall of Fame, one of the best left-handed pitchers in that franchise's storied history and, quite likely, the only candidate for Vermont governor the kid will ever face on any ball field.

Earlier this summer, Lee, who lives in Craftsbury, threw his faded ball cap into the gubernatorial ring. The move was covered by a wide range of local media — not to mention national outlets, such as ESPN, SB Nation and Time magazine. Major Canadian media picked up the story, too, including the CBC, the Toronto Star and the Montréal Gazette — the last of which covered Lee extensively in his volatile Expos days.

Not surprisingly, Lee's candidacy has largely been treated as a novelty — an offbeat political puff piece in a summer when American politics have become increasingly dark and divisive. After all, this is a guy whose main political experience consists of running for president in 1988 as part of the Canadian Rhinoceros Party. That satirical fringe group's platform advocated leveling the Rocky Mountains to give more sunlight to Alberta, Canada, as well as banning guns, butter and the designated-hitter rule.

Lee also claims to have smoked weed with George W. Bush in 1972 under the T. rex exhibit at the Boston Museum of Science. So there's that.

Lee doesn't think his bid for the state's highest office is a joke — though he's quick to joke about it. Asked if leading the state would cut into the significant amount of time he still spends playing baseball — that is, all the time — he replies, "Nah. From what I've seen, it's a part-time job, anyway."

Still, Lee says he feels duty-bound to run. Why? Because he was asked to.

Lee was approached to run by the Liberty Union Party, whose primary claim to fame is introducing Bernie Sanders to Green Mountain politics in the early 1970s. When the LUP came calling, Lee, whose politics align with Sanders', says he had no choice but to accept.

"I don't want to be governor, but I have to be governor," he says, sitting in the Little Fenway dugout before the game — really just some folding chairs along the third-base line. Then, as he's equally wont to do with the works of Buckminster Fuller, Lao-Tzu and Warren Zevon, Lee paraphrases Plato's The Republic:

"Young Plato is sitting in Socrates' lap, and Socrates says, 'The worst thing you can do, Plato, is when asked to run, you do not run, and thereby get governed by a lesser individual.'"

He pauses, his sharp eyes scanning this reporter's face for understanding. When he sees it, he pivots.

"I've got a big head," he says, seeming to allude to his infamous ego. "Watch this."

Lee removes his ball cap, revealing a shock of thick, white hair above a ruddy face cracked by countless innings in the sun. And he laughs, wildly.

As with nearly everything Lee says, it's best to take his words with several grains of salt, ideally rimming a shot of tequila (the Spaceman's taste for rocket fuel is as famous as his eephus). While he's naturally hypercompetitive, he's also naturally charismatic. That could serve him well on the campaign trail — if he's actually in Vermont long enough to kiss babies.

Lee says he's made more than 180 charitable fundraising and goodwill appearances in the past year alone, from Cuba to Canada and points in between. His comfort in the spotlight shows. Before, during and after the Essex Junction game, he's approached constantly — by fans, curious onlookers, journalists and opponents from the various local leagues he's played in over the years. Lee is generous with his time, stopping to talk with everyone, many of whom he knows and remembers by name.

He moves through the crowd with an amiable ease that stands in contrast to his stiffening gait. (When he was asked to play in the game by celeb team coach and local radio host Steve Cormier, Lee dispatched his wife, Diana Donovan, to their car for his spikes ... and three aspirin.)

If baseball were a municipality in Vermont, there is no question who would be mayor. But Lee has his sights set on the state's highest office. Though the odds of him getting there are astronomically small, the Spaceman has spent his career — if not his entire life — thriving as an outsider.

Lifting Off

To understand Lee — to the degree one can — look no farther than the closest baseball diamond. Because there's a good chance he might be on it.

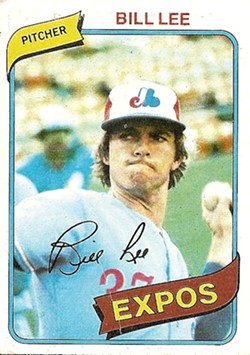

Lee's major-league career ended in 1982 when, as a member of the Expos, he skipped a game and went to a bar to protest the team's release of his friend, second baseman Rodney Scott. Lee was released the next day and will tell you he was subsequently blacklisted from Major League Baseball, and some evidence supports that. It's also fair to suggest that the then-35-year-old junkballer's effectiveness at the sport's highest level no longer offset what a pain in the ass his managers found him to be. But he has never stopped playing.

Lee broke into the big leagues with the Red Sox in 1969. The Burbank, Calif., native was a 22nd-round pick in the 1968 amateur draft out of the University of Southern California. He made brief stops at minor-league teams in Waterloo, Iowa, and Winston-Salem, N.C., before hitting the Red Sox double-A affiliate in Pittsfield, Mass. He clashed with management all the way.

Lee's stay in Pittsfield was short before he was promoted to Boston. His rapid rise through the minors could be attributed to performance — he was dominant at every level. But Hall of Fame catcher Carlton Fisk, Lee's Sox battery mate and minor-league teammate, had a different theory.

In an August 1978 Sports Illustrated article titled "In an Orbit All His Own," Fisk told writer Curry Kirkpatrick he'd suspected the club promoted Lee in the hopes that he would fail and management could be rid of him. It didn't work. Lee thrived as a reliever for four years before becoming a starter in 1973. He won 17 games that season and made the all-star team for the first and only time.

Lee won 17 games the next two seasons, too. And he might have been even better. Had the Sox's flaccid offense been able to provide more runs, Fisk suggested, Lee could have won "24 or 25" games those years. The Spaceman had landed.

"He was one of the better left-handers in all of baseball," says former Boston Globe columnist Bob Ryan. "He was distinguished by persistence. He didn't throw that hard. He gave up a lot of hits. But he knew how to pitch out of trouble. He knew how to set up hitters, how to change speeds and make the most out of not having a blazing fastball."

Ryan was around the Sox for several seasons in the '70s and covered them full time during the 1977 season. That's when Lee's contentious relationship with the team's brass was reaching a messy apex.

Lee was both a messiah and a pariah in Boston. In tie-dyed Cambridge, his lefty sermons to the press on everything from race to global politics to drugs made him a counterculture hero. But in blue-collar enclaves such as South Boston, he was viewed as a freak whose mouth and antics would be tolerated only so long as he kept winning. And even that was a precarious arrangement, as illustrated by Lee's eternal feud with then-Sox skipper Don Zimmer.

"He was in irrevocable conflict with his manager," recalls Ryan. "He demonized his manager in public."

Or at least rodent-ized him. Among Lee's most famous assaults on the bald, portly "Zim" was repeatedly referring to him as a "designated gerbil."

Zimmer, who died in 2014 at age 83, was a stodgy traditionalist. And Lee was, well, Lee: a well-read, well-educated and opinionated hedonist who, at various points in his Sox career, wore a gas mask, a coonskin cap and a propeller-topped beanie onto the field.

"It was not a match made in heaven," says Ryan. "It was made in the other place."

The two clashed constantly and often publicly. Ryan thinks he knows why.

As a promising young player, Zimmer was twice struck in the head by pitches, once in the minors and once in the majors. The first left him in a coma for two weeks. The injuries derailed Zimmer's playing career. Though he was a journeyman in the bigs for a decade, he never realized his immense potential.

"As a result, I don't think he liked pitchers," Ryan opines, echoing Lee's own stated feelings on Zimmer. "I think he had a psychological barrier. He was not sympathetic to their issues or problems. He just thought they should go pitch.

"And it just so happened that the most iconoclastic player that has probably ever worn a Red Sox uniform happened to be a pitcher," Ryan continues. "And he happened to be in the uniform at a time when his manager was a less-educated, straightforward baseball lifer who didn't remotely understand people such as Bill Lee."

Lee wasn't the only Sox player to clash with Zimmer. One by one, the Sox dispatched Lee's friends and fellow agitators, pitchers Ferguson Jenkins, Rick Wise and Jim Willoughby, to other teams. When the team sold outfielder Bernie Carbo to the Cleveland Indians in 1978, Lee staged a one-man, one-game walkout in protest. Coupled with his diminished effectiveness — his left shoulder had been dislocated in a famed 1976 brawl at Yankee Stadium — that finally gave the Sox an excuse to send him packing. Lee was traded to Montréal in late 1978 for utility infielder Stan Papi.

Crash Landing

Lee rebounded to a degree with the Expos and quickly became a fan favorite — as much for exploits off the field as on it. But he continued to be a thorn in the side of management, up to and during his 1982 release.

This era of Lee's life inspired the new film Spaceman, from writer-director Brett Rapkin, starring Josh Duhamel in the title role. It premieres with a special screening at Fenway Park this Friday, August 19, and will be shown at select theaters around the country — though none in Vermont — and on video on demand. Based on a portion of Lee's 1984 autobiography The Wrong Stuff — cowritten with his friend Dick Lally — it tells the story of the weeks immediately following Lee's Expos exile, which Lee calls "the worst two weeks of my life."

The movie opens with a bare-assed Lee/Duhamel sprinkling marijuana on his pancakes. Lee's pot consumption had become part of Spaceman lore during an interview with a Montréal media outlet that was investigating a reported "drug problem" in the Expos' locker room. Lee told the reporter that weed had made him impervious to bus fumes when he jogged to Fenway Park during his time in Boston, then added that he preferred it on his flapjacks. That claim supplies a perfect flourish for the Spaceman's cinematic legend — although, according to both Lee and Donovan, Lee never actually put weed on his pancakes. He prefers maple syrup.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Bill Lee hits a homer

If the weeks chronicled by the film were Lee's all-time low, they may have also proved among the most formative for his later life. As Rapkin puts it to Seven Days, "No one loves baseball, lives baseball, as much as Bill. He's forever searching for that next game."

And that searching has shaped Lee's later years. Unable to hook up with another MLB team after Montréal, he bounced around the hemisphere, playing semi-pro and amateur ball from Venezuela to New Brunswick. He landed in Vermont in 1988. Currently, Lee plays for the Burlington Cardinals in the Vermont Senior Baseball League, an amateur club he has frequently called the "best team I've ever played on."

This might be a good time to point out that Lee started two games in the 1975 World Series. In 2012, at 65, he became the oldest player ever to win a professional game, for the independent San Rafael Pacifics. The next year, he did it again for the same team, breaking his own record.

"It's probably safe to say he's the best pitcher his age on the planet," says Burlington attorney Tom Simon. "Granted, there aren't that many."

Simon is Lee's teammate on the Cardinals. He is also a baseball historian and author, as well as the founder of the Vermont chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research. Simon says that, even at 69, Lee is one of the Senior League's best all-around players — the pitcher has always prided himself on his ability to hit, and he still fields well. At the start of each season, Simon relates, someone from another team unfailingly proposes a thinly veiled rule change that would oust Lee from the league.

"It's always something like, 'no former pros allowed,'" says Simon. "But it's pretty obvious who it's aimed at." He adds that Lee only joined the Cards after a manager in another regional amateur league kicked him off a team several years ago. Even in old-man rec leagues, the Spaceman is an alien.

Yet Simon describes Bill as a good friend and an even better teammate. That's evident at a recent Cardinals game on a Sunday afternoon at SD Ireland Field in Burlington's Calahan Park. Lee pitches a complete game — a win for the home team — working in and out of trouble and allowing only two unearned runs.

The respect and admiration Lee's fellow Cardinals have for him is obvious. In the dugout, they gather around him as he opines on everything from the current opposing pitcher's habit of hanging breaking balls to his feelings about Atlanta Braves Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Glavine: "I hated him. He never did anything wrong. He didn't drink; he didn't smoke. He didn't even sweat. In Atlanta, for crissakes!"

The Cards are not without other intriguing personalities. The starting shortstop is Galen Carr, formerly a scout for the Red Sox and currently the director of player personnel for the Los Angeles Dodgers. At second base is George Lambertson, the executive chef at ArtsRiot. The team's most fearsome hitter, a drug enforcement agent named Adam Chetwynd, plays first base. And behind the plate stands Lee's catcher, Miro "Mo" Weinberger, mayor of Burlington.

Still, it's Lee who attracts a crowd, though it's a modest one today. Watching by the backstop is an elderly couple from Montréal. On their way to a Vermont Lake Monsters game that evening, they stopped by the Cards game for a glimpse of the Spaceman.

"That actually happens a lot," says Weinberger.

Spaceship Earth

Lee doesn't own a cellphone and has no use for computers. Until recently, if you called Lee's home and got the answering machine, you would have heard the following message: "You've reached the governor's mansion. It's located exactly halfway between a bar in Boston and a bar in Montréal."

Might Lee's halfway house become the residence of Vermont's next governor in November? You'd have a hard time finding anyone who thinks so — save perhaps Lee or Donovan, and probably not even them. It's fair to ask if Lee's own party believes he can win. Or if it knows he's running.

As of this writing, the Liberty Union Party's Facebook page makes no mention of Lee. His name appears only once on the LUP website — in a post about the June 2 potluck fundraiser in Cabot where he announced his candidacy.

Nonetheless, Lee garners plenty of attention. Perhaps too much.

"The amount of ink he's received will far outpace his votes," says Garrison Nelson, a Sox fan and political science professor at the University of Vermont. "I have great fondness for Bill Lee," he adds, recalling a Sox game that Lee entered wearing his uniform backward. "He's a colorful distraction. He'll have no impact on the race, but he'll be far and away the most interesting of all the contenders."

Dan Turner is an Ottawa writer who has published several books on baseball in Canada, including The Expos Inside Out in 1983 and Heroes, Bums and Ordinary Men: Profiles in Canadian Baseball in 1988. The latter book included a chapter titled "The Spaceman," written while Lee was playing for a sandlot team in Moncton, New Brunswick, and "campaigning" for the Rhinoceros Party. It's not clear whether Turner files Lee in the "heroes" or "bums" category. Possibly both.

"I think of Bill as kind of the anti-Trump," Turner writes in an email, referring to Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump. "They're both performers and have spent their whole lives developing their brands. Neither should ever be elected to run anything serious, like the country or even a state. Their main value is making the mainstream look ridiculous, which to a large extent it is.

"Bill's all for the underdog," Turner continues. "Donald is an overdog guy. I prefer Bill, but you can never forget that, like Trump, he's a performer."

Yet recent history indicates that colorful, charismatic characters can impact elections, even profoundly. And here's an interesting wrinkle: In Vermont, a candidate for governor needs to win with not merely a plurality of votes but a majority — more than 50 percent. If no candidate wins the majority, the Vermont General Assembly decides the race. Could Lee siphon enough votes from Democrat Sue Minter and Republican Phil Scott to activate such a vote? Does anyone know the breakdown of Sox versus Yankees fans in the legislature?

As recently as 2014, the governor's race was decided in the Statehouse. And it's not unprecedented for the pesky LUP to rouse enough rabble to matter. In 1976, Liberty Union candidate John Franco tilted the lieutenant governor's race and sent it to the legislature.

Nelson, who has been teaching politics at UVM since the year Lee was drafted by Boston, is probably correct that the Spaceman's effect on the race will amount to little more than stardust. LUP cofounder Peter Diamondstone, speaking to the Burlington Free Press last month, admitted as much, saying, "We're not going to change the world, so we might as well smile a little."

But suppose for a minute that they're wrong. To borrow the painfully obvious pun that headlines roughly 75 percent of the stories on Lee's candidacy, what would be his — wait for it — pitch for the governor's office?

To be sure, some of Lee's platform is reasonable — establishing universal health care and higher environmental standards, combating the state's opioid epidemic and augmenting ride-share programs for rural elderly Vermonters. But other ideas are ... out there. For example, Lee suggests replacing the Vermont Agency of Transportation's mowing equipment with farm animals to trim highway medians — and the agency's budget. He'd also dissolve our northern border to allow unrestricted travel between Vermont and Québec. And he'd merge the state with the Canadian province in the event that Trump becomes president.

Lee has baseball proposals, too, of course. Among them is inducting steroid users into the MLB Hall of Fame. He would also attempt to bring baseball back to Montréal by moving the Tampa Bay Rays.

"I'll rename them the Ex-Rays," Lee says, chuckling.

While a Vermont gov has exactly zero authority to move an MLB franchise from Florida to Canada, Lee's baseball platform has swayed at least one voter.

"I'm voting for him," says Simon. "He'll be great for baseball in Vermont."

Lee already is that. If he's to become more, he has a long, uphill fight ahead of him. But those who would outright dismiss his chances should remember the lesson learned by his opponents, from Yankee Stadium to Little Fenway: When he gets in a game, Bill Lee always plays to win.

The original print version of this article was headlined "The Spaceman Who Would Be King"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Outdoors & Recreation, Baseball, Bill Lee, cannabis related, gubernatorial race, Sports, Travis Roy Foundation Wiffle Ball Tournament, Video

More By This Author

About The Author

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of...

-

UVM Swimming and Diving Overcomes Budget Cuts to Win Conference for the First Time in Its History

Mar 13, 2024 -

Two Vermont Teens Take On the Cross-Country Junior National Championships

Mar 6, 2024 -

Youth Soccer Comes of Age in Vermont, but the Playing Field Is Hardly Level

Nov 1, 2023 -

A Book About Halloween — and Baseball — That’s More Silly Than Scary

Oct 25, 2023 -

In a Classic Vermont Mountain Road Rally, Winning Takes Precision and Smarts, Not Speed

Sep 20, 2023 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Rev. Nathan Strong 'Was Just a Good Ol' Country Boy' Life Stories

- 2. Q&A: Catching Up With the Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Bookstock Literary Festival Abruptly Folds Books

- 4. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, April 17-23 Magnificent 7

- 5. Two Vermonters Awarded Prestigious Guggenheim Fellowships Books

- 6. It's Time to Pick Your Daysies! 7D Promo

- 7. My Adult Sister Is Obsessed With American Girl Dolls Ask the Rev.

- 1. Rep. Anne Donahue Is Determined to Find Out Where Patients of Vermont’s Old Psychiatric Hospital Are Buried Politics

- 2. Video: Digging Into the Ravine That Divided Burlington in the 1800s Stuck in Vermont

- 3. A New Film Explores Vermont’s Unsung Modernist Buildings Film

- 4. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Planned Burlington History & Culture Center Would Focus on the Regular Folks Who Built the City History

- 6. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse

![16th Annual Travis Roy Foundation WIFFLE Ball Tournament [SIV501]](https://media2.sevendaysvt.com/sevendaysvt/imager/u/square/7496420/episode501.jpg)