Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Staying Alive: The Highs and Lows of Overdose-Reversing Narcan

Published December 9, 2015 at 10:00 a.m.

"My son dropped dead in there," the sixtysomething man told a reporter, pointing toward his bathroom. His pronouncement was only slightly hyperbolic.

After attempting to quit heroin, "George" said, his son misjudged how much his body could handle. As the passed-out addict's lips turned blue, his father located a plastic syringe fitted with a foam head. He inserted the foam end into his son's nostril and pushed the plunger. A moment later, the younger man was awake and breathing.

The drug George administered was Narcan, which counteracts opiate overdoses. He had it on hand that day because of a three-year state pilot program that's been providing it free of charge to addicts and their friends and family. George is also opiate-dependent, so it's conceivable his son could be called on to return the favor.

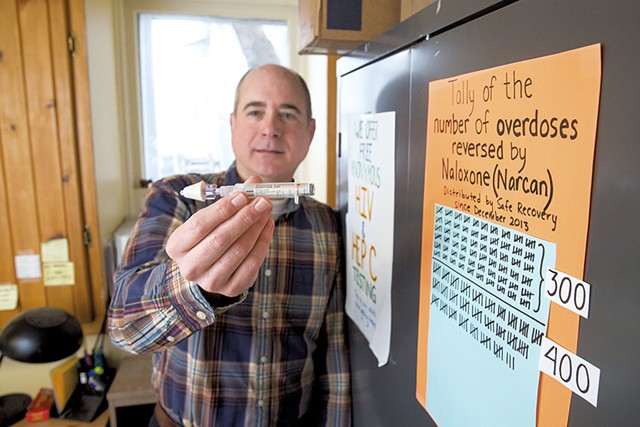

In the two years since the program started, Vermont policy leaders, cops and addicts alike have heralded Narcan as a "miracle drug." Nearly 7,000 Narcan kits have been distributed through 10 treatment facilities, recovery centers and needle-exchange programs statewide, and recipients have reported using the drug more than 400 times to reverse overdoses as of September. The total number is likely higher because not everyone checks back in after using it.

Simply put, Narcan helps opiate addicts who aren't in treatment to stay alive. Most people have welcomed it in a state where at least 55 people — and counting — have died this year from opiate overdoses, and more than 600 are on waiting lists for drug treatment.

"I don't know how you advocate against it," said Vermont State Police Colonel Matthew Birmingham. "It saves lives. It's proven."

Chittenden County State's Attorney T.J. Donovan said that Narcan can serve as a "wake-up call" and a "portal into treatment."

But Birmingham and Donovan don't speak for everyone in the effort to address Vermont's opiate-addiction crisis. Some law-enforcement officers have philosophical objections to mass-distributing the drug, claiming it encourages reckless behavior and actually discourages addicts from getting clean. The Burlington police union has a practical problem with it: Administering death-defying medication is not in their current job description.

Meanwhile, Vermont law requires the Department of Corrections to make Narcan kits available to inmates who are being released from prison, but no one has been offering it to them.

Even Vermont Health Commissioner Harry Chen worries Narcan may send a dangerous DIY message to addicts: that they can manage their own overdose emergencies without calling 911. Another challenge on the horizon: The cost of the drug has risen precipitously, and officials are signaling that they won't be able to give it away free forever.

Lobbying for Life

Narcan, the most common brand name for naloxone hydrochloride, isn't a new invention. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 1971, and emergency room doctors and EMTs have been using it to revive people for decades.

But in 2013, few Vermonters outside the medical profession had heard of it. Similarly, the state's growing opiate problem was still under the radar. That didn't stop House Speaker Shap Smith (D-Morristown) from asking two committees to start work on a bill that addressed it — a full year before Gov. Peter Shumlin made it the centerpiece of his now-legendary State of the State address.

The House Committee on Judiciary heard testimony from Tom Dalton and Grace Keller of the Howard Center's Safe Recovery program — a Burlington-based needle exchange that offers HIV testing and provides general support to people struggling with drug addiction. The two reported they had begun to see clients dying from overdoses. They came to the Statehouse to urge lawmakers to support a "good Samaritan" bill granting legal immunity to anyone seeking medical help for an overdose.

Dalton pulled the bill's sponsor, Rep. Bill Lippert (D-Hinesburg), aside to tell him about something called Narcan. "I can tell you, personally, I had no idea what he was talking about it," recalled Lippert, who was then the committee chair. "We knew nothing about it."

Opiates send signals to receptors in the brain, sparking feelings of pleasure and dulling sensations of pain. But too much can slow — or stop — respiration, which is the most common cause of death during an opiate overdose.

Narcan is administered as a nasal spray or a needle injection — nothing like the adrenaline injection to the heart that John Travolta delivered to revive Uma Thurman from a heroin overdose in the movie Pulp Fiction. Narcan works by disrupting the drug's chemical connection in the brain. Although it can take multiple doses, the drug's effect is almost always immediate. Within a few minutes, the person wakes experiencing withdrawal symptoms — sweating, shaking, dizziness and severe nausea.

Dalton suggested to Lippert that this obscure drug should be distributed to the masses. Although it sounded radical at first, Lippert's committee warmed to the idea. The group heard from people running successful community distribution programs in Chicago and Massachusetts, who said the risks were minimal: Narcan is easy to administer; it isn't addictive; and, if mistakenly used on someone who hasn't taken opiates, it has no effect.

In the end, the Vermont Department of Health agreed to create a three-year pilot program without any additional appropriation. It would get a prescription for Narcan, develop a training manual and distribute the antidote to treatment centers that would teach their clients how to use the drug at home.

All but one judiciary committee member approved, and the legislature voted overwhelmingly in favor of the final bill, which both democratized access to the antidote and eliminated concerns about being prosecuted for using it.

In December 2013, Safe Recovery became the first pilot site to receive the drug from the health department. Nine syringe exchanges, treatment facilities and recovery centers — in Bennington, Berlin, Brattleboro, Middlebury, Newport, Rutland, St. Albans, St. Johnsbury and White River Junction — followed its lead.

Staff at Safe Recovery started offering Narcan to everyone who came through their doors. Keller said she gave out 60 doses on a single day. She's administered it several times, too, to save clients. On one occasion, someone brought in a young man who'd stopped breathing. Another employee called 911 while Keller calmly gave him Narcan. Nothing happened. After a second dose, she started performing rescue breathing. After the third dose, he woke up immediately and started asking questions: "Who are you? What's going on?"

As of September, Keller and her colleagues had handed out more than 2,500 kits to clients who've reported using it 366 times to reverse overdoses — the bulk of the known incidences. Three of those can be attributed to George, who said he's used Narcan on two other addicts in addition to his son.

Serve, Protect — and Spray?

In January 2014, the Shumlin administration announced that all state troopers would keep Narcan in their cruisers. Then-colonel Tom L'Esperance called it the "easiest decision I've ever had to make." The Vermont Department of Public Safety pays for the drug, which is supplied by the health department. Troopers have "deployed" it six times so far this year, according to Birmingham. Even when the EMTs have arrived first, it's proven essential.

On April 23, a mother called 911 after finding her 19-year-old son, Kenneth Sypher, unconscious on the kitchen floor of their Bethel home. When the White River Valley Ambulance squad arrived, they gave him five doses of Narcan. They'd exhausted their supply, and Sypher still hadn't stirred. But by that time, four state troopers had also arrived, each carrying Narcan. The ninth and final dose revived the teen, who police later determined had used heroin spiked with fentanyl, a more potent drug that requires larger quantities of Narcan to counteract.

The practice — of bringing addicts back to life — is catching on among local law-enforcement departments. A tally by the public safety department at the beginning of the year found that 10 chiefs had equipped their officers with Narcan. Several others, including in Richmond and Barre City, have embraced it since that count.

EMTs at the Burlington Fire Department have carried Narcan for decades. In a city where overdoses have been on the rise, in a county with a 300-person waiting list for treatment, one might assume that Burlington's 100 or so police officers would be carrying it, too.

They haven't been.

Behind the scenes, Narcan has been the subject of a disagreement between the police administration and the union representing officers, which are in the midst of a protracted contract negotiation. The union has argued that carrying Narcan constitutes a new duty and therefore needs to be approved as part of the collective bargaining agreement.

"It's a change of work," said Officer David Clements, who is the union president. "It's a medical procedure that's not something we have provided."

Burlington officers aren't the only ones who've made this argument. In Somerville, Mass., officers objected to being required to carry Narcan on the grounds that it was an expansion of their duties and therefore a breach of their contract.

Chief Brandon del Pozo, who took the reins in September, has maintained that he can mandate it unilaterally. He plans to do so before the end of the year — with or without the union's blessing.

Del Pozo said he's sympathetic to the Burlington union's position — but only to a point: "I think that's a valid concern, but considering how easy Narcan is to administer and ... how it's been demonstrated to save lives ... it seems a reasonable expansion of our responsibilities." A moment later, he corrected himself — "Not an expansion; it's an evolution."

According to Clements, the union is "not necessarily" seeking additional compensation. "Most of the concerns are about how it's going to be carried out," he said, of the protocols for how and when Narcan will be used. When someone is revived with Narcan, "things can go a little crazy," he noted, meaning there's the potential that an individual under the influence would respond violently.

Del Pozo started training officers last week, and he's in the midst of drafting the department's Narcan policy. If they have a say in matters related to safety, Clements expects members will come around to the idea. "I don't view it as a bad thing. It's just something we've never used before," he said.

'See Ya Later'

Steve Prevost's road to jail was paved with ill-gotten opiates. The Winooski construction worker recalled the rapid progression of his drug addiction, which began when he was a teen cycling through foster homes: "You start sniffing Percocets, eating Oxys and then you're shooting heroin," he said.

His drug habit led him to steal, which landed him in prison in 2001, at age 20. He did his two and a half years in Greenville, Va., and soon after being released, met up with a childhood friend. The two were in Burlington when they got into a car with a heroin dealer Prevost had met in prison. They had already split three six-packs.

As he injected two bags of heroin in the passenger seat, Prevost noticed his friend, who shot up first, gasping for air in the backseat — a sign that he was overdosing.

"Not knowing CPR, I was trying to blow air into his lungs," he said. "The last thing I remember was a mouthful of his spit in my mouth. Then everything went black."

Like his friend, Prevost had overdosed. Although he occasionally scored dope in prison, he was mostly clean at the time, he said, and his body couldn't handle that much heroin.

Seventeen hours later, Prevost woke up vomiting and alone in an unfamiliar apartment. His friend, he would later learn, had also survived. Prevost eventually sought help at Safe Recovery, where staff helped get him into treatment. After multiple relapses, he's been clean for two and a half years.

In 2014, the legislature passed a bill requiring the Department of Corrections to work with the health department to distribute Narcan to people such as Prevost — outgoing inmates with a history of drug abuse. Correctional facilities already stock the drug in case someone needs it behind bars, but studies show that incarcerated drug addicts are disproportionately likely to die from an overdose during the first few weeks after they've been released from prison.

A year and a half later, inmates are still leaving Vermont jails empty-handed.

Corrections Commissioner Lisa Menard struggled to explain the delay. "I'm just going to acknowledge that it does seem like a long time," Menard said. The challenge, she said, has been purely logistical — "It's not as simple as, 'Here's a kit; see ya later.'"

The corrections department still doesn't have a prescription, but it has begun to prepare staff to teach departing prisoners how to administer Narcan.

Meanwhile, on December 1, Shumlin announced another program for outgoing inmates with opiate addictions. Prisoners who've gone through detox and have been released from the Marble Valley Regional Correctional Facility in Rutland can now receive naltrexone, which discourages opiate use by blocking its euphoric effects. Officials say this initiative, funded through a federal grant, will start promptly — in January.

Of the Narcan program, Menard said, "I would expect it to happen in the near, near future." At least at first, the DOC will only offer it in two correctional facilities: St. Albans and Chittenden.

The commissioner explained, "We're certainly not ruling out at some point it would be given to everyone, but initially I think it would be better to plan and understand any consequences, positive or negative."

Other institutions don't make such distinctions. According to Dalton of Safe Recovery, "We started handing it out the day we got the medication from the health department. It's not complicated."

After a rash of overdoses involving fentanyl in the Upper Valley last year, the Hartford School Board voted in August to give Narcan to school nurses.

Perfect Prescription?

The argument for universal access to Narcan is simple: It's resurrection in a nose spray.

But not everyone is a believer. "It's certainly accepted, but it's not widely accepted," Donovan said. "We gotta continue to push the rock up the hill."

Birmingham acknowledged that within his ranks, some still harbor reservations, and "that's a philosophical view troopers are entitled to have."

As a patrol commander at the Royalton barracks, Sergeant John Helfant deals with opiate-related incidents on a near daily basis.

"I'm fine with carrying Narcan, and if I have the opportunity to use it, I'd definitely use it," Helfant said. But he also worries that it makes addicts more cavalier about pushing the limits. "It makes them too comfortable," he said. "We have seen it. They are just not concerned about the dosage or the quantity." Warning against viewing Narcan as a cure-all, Helfant pointed out that it can take multiple doses to revive someone, and the antidote can wear off.

Tim Bombardier, the Barre City police chief, said he views Narcan as just another tool law-enforcement officers can use to save lives; he plans to distribute it to his officers as soon as they've been trained. But Bombardier takes issue with the practice of handing it out at treatment centers. "That seems a little two-sided to me," he explained. "If the point is to help people stay clean, why are we giving you Narcan in the same breath?"

As part of the training they receive with the kit, people are instructed to call 911 after administering Narcan — in part because, as Helfant pointed out, it can wear off before the opiates have cleared an individual's system. But according to health department data, only 28 percent of people have heeded this instruction.

"It continues to be a concern," said Chen, adding, "I don't know that there's a way around it." He conceded, though, that the lengthy waiting lists for treatment statewide suggest that Narcan isn't stopping people from trying to get clean.

Sarah Clark went to rehab a half- dozen times before she stopped abusing opiates, and the 36-year-old Essex Junction mother has been drug-free for five years. She carries Narcan, just in case she encounters someone who's overdosed. "A lot of people have been saying it's not good because it encourages people to do drugs," she said. Her rebuttal? "You need to be alive to go to treatment."

But getting help could get harder — at least in Chittenden County. Safe Recovery recently lost a $450,000 federal grant that funded 80 percent of its operations because it was tied to HIV prevention — and Vermont's infection rate has dipped below the qualifying threshold. The grant-supported staffers also distributed Narcan and ran the needle exchange. Most of them have already been laid off.

After applying for other grants without success, Dalton, Keller and their boss, Bob Bick, CEO of the Howard Center, are calling on the state to fill the funding shortfall.

They've got some influential allies. Donovan, who sits on the Howard Center's board, said he thinks the Narcan movement will suffer if Safe Recovery can't secure replacement funding. Lippert is also dismayed. "We would not have Narcan available to Vermonters in the same way if it weren't for the commitment and initiative of Tom Dalton and Grace Keller. The idea that their program is subsequently in danger ... is, for me, particularly difficult to comprehend."

Cough It Up

Early next year, Narcan's future in Vermont will come up for debate. With the state's pilot program scheduled to conclude next June, lawmakers will have to confront the question of cost in a comprehensive way during the upcoming session. The health department is drafting a report for lawmakers, evaluating the program. In the meantime, it's no longer offering Narcan to new sites.

Asked last week to give a preliminary appraisal, Chen responded, "Overall, successful." But, he continued, "I think the question really is, is it a sustainable model for the long-term?"

The give-it-away-for-free approach? "That's something I think we're going to have to rethink," he said.

Since the program started, the cost of the drug has skyrocketed — in response to increased national demand.

In April, Shumlin sent a letter to the Narcan manufacturer, Amphastar, urging the company to reduce the price. He noted that the health department paid $113 for 10 doses of Narcan in March and $183 for the same amount in April.

Several states have struck deals with the pharmaceutical company, securing a discounted rate. Vermont has yet to score such an arrangement, but the governor's spokesman, Scott Coriell, told Seven Days that the administration is discussing possibilities with Amphastar.

Amphastar has enjoyed pricing discretion in part because it's offered the only version of Narcan that can be converted into a nasal spray. Its product is actually sold as a syringe, but an atomizer, purchased separately, turns the syringe into an intranasal device.

In November, the FDA approved a nasal spray made by Adapt Pharma, which doesn't require this extra step. When the new product hits the market in January, Chen expects it to "help substantially."

Although his department has been footing the bill, the total tab for the pilot program has been modest — $165,000 from its start in 2013 to September 2015.

Long-term, though, the health commissioner plans to advocate for a more traditional — and cheaper — method of dispensing Narcan: pharmacies.

Last year, Vermont changed its laws in order to allow pharmacies to dispense the drug over the counter — yet pharmacists at Rite Aid, Walgreens and Kinney Drugs in Burlington confirmed that their employers have yet to stock it. Even if they do, customers would be paying for it out-of-pocket.

Chen's vision is to make Narcan available at pharmacies, without a prescription — or, more likely, with a standing prescription that would apply to all Vermont residents — and make Medicaid or private insurance pay for it. That would require convincing pharmacies to stock it and getting insurers to cover it. The health department would likely continue to supply Narcan to certain locations to reach people who wouldn't otherwise seek it out.

Regardless of the method, key lawmakers say they're committed to continuing to expand access to Narcan. "In the midst of this tragic epidemic, for me it's a given that we should have it widely available, without financial barriers," Lippert said.

"We'll find a way," promised Sen. Dick Sears (D-Bennington).

Prevost hopes so. "It's such a simple thing," he said. Even if the cost were to continue to rise, he suggests a litmus test for lawmakers: "What if your son was a drug addict? Would you spend 40 dollars to keep him alive?"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Health Care, FDA, Narcan, opiate addiction, opiates, Opioid Crisis, overdoses, prescription drugs

More By This Author

About The Author

Alicia Freese

Bio:

Alicia Freese was a Seven Days staff writer from 2014 through 2018.

Alicia Freese was a Seven Days staff writer from 2014 through 2018.

About the Artist

James Buck

Bio:

James Buck is a multimedia journalist for Seven Days.

James Buck is a multimedia journalist for Seven Days.

Speaking of...

-

'Safe Haven': Vermont Is Considering Controversial Overdose-Prevention Sites. 'Seven Days' Went to New York City to See One.

Mar 20, 2024 -

The Fight for Decker Towers: Drug Users and Homeless People Have Overrun a Low-Income High-Rise. Residents Are Gearing Up to Evict Them.

Feb 14, 2024 -

Backstory: The ‘Saddest Update’ on an Opioid-Addicted Source

Dec 27, 2023 -

Vermont Lawmakers May Have to Meet Growing Problems With a Shrinking Budget in 2024

Dec 20, 2023 -

New Burlington Health Clinic Will Serve People Struggling With Drugs

Nov 15, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis

- 2. Ed Secretary Saunders Fields Questions at Confirmation Hearing Education

- 3. Vermont Reports Its First Case of the Measles Since 2018 News

- 4. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 5. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 6. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 7. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. Burlington City Council Approves Rezoning Plan to Boost Housing Supply News

- 5. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 6. Rising Costs and Property Tax Hikes Again Threaten the Survival of Small Schools Education

- 7. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News