Published August 1, 2012 at 9:55 a.m.

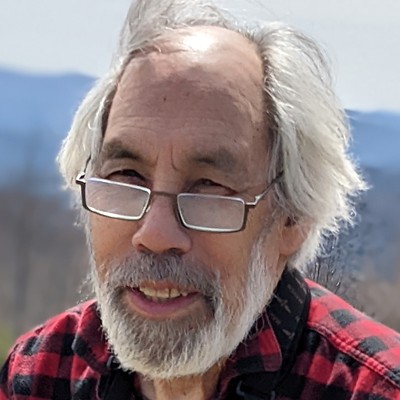

Rick Sharp has been arguing with the City of Burlington for more than three decades about its waterfront. Largely credited with the creation of the Queen City’s crown jewel, the 59-year-old attorney and environmental activist now just wants to be able to lead Segway tours on the 7½-mile Burlington Bike Path.

He may get his wish. In his latest battle with municipal officials, Sharp has been trying to convince Parks and Rec director Mari Steinbach that the electric-powered “personal transporters” would enable the disabled to enjoy Queen City attractions that might otherwise remain inaccessible to those, like himself, who can’t ride a bike or easily walk.

The Kiss administration didn’t like the idea of motorized vehicles on the bike path or downtown sidewalks, quashing Sharp’s plan for starting a Segway tour business. The city has no formal policy on Segway use, notes Steinbach, but for now, “We’re not under any obligation to allow commercial operations on the bike path.”

Mayor Miro Weinberger recently issued Steinbach her walking papers. And the new mayor sounds more sympathetic to the proposal by Sharp, who supported Weinberger in the race to succeed Kiss. “I find his perspective about the freedom and dignity the vehicles can provide to some individuals with disabilities very compelling,” Weinberger comments in an emailed statement. “His beliefs in Segways as an economic development opportunity and as an environmentally superior option to the car for many types of vehicular trips are also interesting to me.

“I support a review of the city’s policies regarding these devices,” adds Weinberger, who will soon name a replacement for Steinbach.

While a Segway does offer a noiseless, nonpolluting ride at a maximum speed of 12 miles per hour, a recent late-afternoon ramble with Sharp and his wife, Ruth Masters, attracted dirty looks from a few pedestrians along the congested segment of the bike path near the Community Boathouse.

Sharp maneuvers his Segway — one of nine he owns — with confidence and a big smile. He otherwise moves slowly and painfully with the help of a cane and a brace on his right leg from knee to ankle. Those assists represent the final phase of a recovery that began with a wheelchair and then progressed to a walker.

Sharp is actually lucky to have any mobility at all. He says he came within 30 minutes of suffering life-long paralysis after crashing into a cliff while paragliding off a promontory on Mexico’s Pacific coast in 1996. The accident occurred as Sharp was serving as a “wind dummy” — the tour leader who tests whether wind speeds are safe for paragliding. They weren’t that day.

It took seven and a half hours to transport him to a hospital in San Diego for treatment of two broken vertebrae and a crushed leg. Paralysis often results from such injuries unless steroids are administered within eight hours, Sharp notes. Paradoxically, “that accident probably saved my life,” he reflects. “I probably would have kept taking crazy risks if it hadn’t happened.”

There’s an especially sad irony in Sharp’s inability today to ride a bike. “If he hadn’t been involved,” says former governor Howard Dean, “there probably wouldn’t be a Burlington Bike Path.”

Dean, Sharp and University of Vermont environmental studies professor Tom Hudspeth were the leaders of a Citizens’ Waterfront Group formed in the late 1970s to advocate for converting what was then a disused waterfront rail line into a bike path. Over this and other waterfront controversies, the trio went to battle with Democratic mayor Gordon Paquette and, starting in 1981, Socialist mayor Bernie Sanders.

“The Paquette administration didn’t like us because we were too liberal,” recalls Dean, who was not an elected official at the time. “The Sanders administration didn’t like us because we were Democrats.”

The chief nemesis of bike-path supporters 30 years ago was New North Ender Paul Preseault, who owned property on both sides of the rail line’s right-of-way and would not sanction its use by bicycles. Preseault dramatically expressed his opposition by blocking the path with a log. Long legal tussles ensued, culminating in a pair of U.S. Supreme Court rulings in 1988 and 1990 in support of turning the rails into a trail. Sharp celebrated the victory by chainsawing the log — at which point Preseault came running out of his house and assaulted Sharp. “I barely had time to turn off the chain saw,” Sharp recalls. “It could’ve been really ugly.”

Preseault died in 2010 at age 76.

Noting that he voted for Sanders in the historic 1981 mayoral race, Sharp says the radical politician did favor creation of the bike path — just not as enthusiastically as did the leaders of the Citizens’ Waterfront Group.

Where Sharp and Sanders really clashed was over an early-’80s waterfront development proposal known as the Alden Plan. Private developers were calling for construction of a marina, a public boathouse, 65,000 square feet of retail space, 145,000 square feet of offices, a 200-room hotel, 300 mainly up-market housing units and a pair of parking structures that could accommodate 1200 cars on what eventually became Waterfront Park.

Hudspeth, who refers to it as “a mini-Acapulco,” says the Alden Plan might have come to pass if not for Sharp’s “invaluable and tireless legal work.” Sanders supported the Alden proposal, as did 12 of the 13 members of what was then called the Board of Aldermen — the predecessor of the Burlington City Council. But the city needed to issue a bond in order for the project to move forward, with a two-thirds majority required for approval of that initiative. The Alden Plan bond received 54 percent of the vote in a 1985 referendum — and was thus defeated.

At around the same time, Sharp was fighting to win legal recognition of what was known as the public trust doctrine. It forbids commercial construction on waterfront land created by fill. A 1989 Vermont Supreme Court ruling upheld the doctrine as applied to the Burlington waterfront, thus ensuring that only public uses are possible on most of the land closest to Lake Champlain between North Beach and Perkins Pier. That’s why a park, boathouse, museum and “urban reserve” are in place there today rather than condos, stores and offices.

With the Alden Plan off the table, the Sanders administration threw its support behind the public trust doctrine, with then-city attorney John Franco playing a visible role. “Franco did a good job and he gets the credit for what happened, but Rick was on it before he was,” Hudspeth remarks.

Partisan divisions account in large part for the animosity between Sharp and the Sanders administration and its Progressive allies. “Rick has a personality that can piss people off,” Dean observes, “but hopefully those feelings are behind us now.”

Sharp twice ran unsuccessfully as a Democrat against Progressive Gene Bergman for a seat on the Board of Aldermen. In those super-heated 1980s races, Sharp came under attack for his role as a landlord of dozens of student rental units in and near downtown. He was accused of gouging tenants while maintaining poor-quality housing. Sharp rejected those charges and has since sold off all but five of the apartments. “That was my retirement plan, and we’ve gotten rich from it,” Sharp says, “so we’re getting out of it now.”

Sharp traces the origins of his passionate involvement in environmental causes back to the paper companies along the Connecticut River when he was a boy in Bellows Falls. They used to dump dye into the water that “would turn the river red, green and orange,” Sharp remembers. “It was really bad.”

Raised by his stepmother who was dependent on Social Security, Sharp earned a full scholarship to the University of Southern California. In 1978, he got a degree from Georgetown Law School, and then returned to Vermont for a job with the state’s environmental conservation agency.

Sharp and Masters, who have two grown daughters, live today in Colchester and spend time on a 100-acre property in Milton they bought several years ago. It’s the site of a Christmas-tree farm that provides the couple with more income, Sharp notes, than does the other business he runs there: conducting paragliding lessons.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Man Charged With Arson at Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 7, 2024 -

Police Search for Man Who Set Fire at Sen. Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 5, 2024 -

Bernie Sanders Sits Down With 'Seven Days' to Talk About Aging Vermont

Apr 3, 2024 -

Sociologist and Author Nikhil Goyal Talks Education, Books and Bernie

Dec 6, 2023 -

Rep. Balint Reverses Course, Calls for Cease-Fire in Gaza

Nov 16, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.