Published February 2, 2016 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated April 4, 2022 at 8:02 p.m.

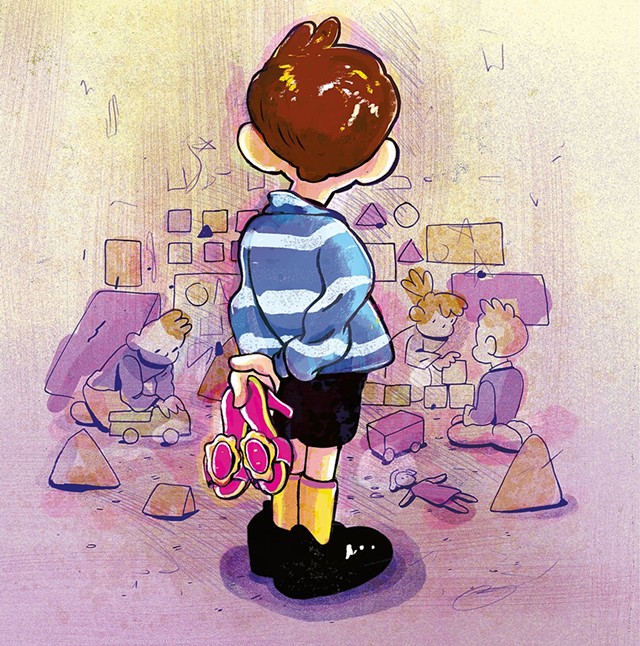

The best present "Willow" received on her ninth birthday wasn't a bike or a doll, but a court document in a manila envelope. Inside was a new birth certificate, on which the gender had been officially changed — from male to female.

"I am one of the first people to ever do this," Willow said a few days later, snuggled up between her parents on a comfortable couch at their rural home in northern Vermont. The state allows individuals to change their birth records if they've completed medical treatment for gender transition, and plenty of trans adults have done so. But because Willow is too young for either hormone therapy or surgery, the judge used different legal logic to come to a decision — after three court dates, and testimony from Willow, her psychologist and her pediatrician.

Her dad "James" explained: "The standard of the law is that you have to have completed treatment. And the argument that we then made ... was that for a child her age, there is no medical treatment, so she has completed the medical treatment ... but it was a complicated process because as far as we could tell there wasn't a precedent ... There could be other children just like her, but those records are sealed."

Although there will be more forms to change, and bureaucratic battles to fight, with this document Willow will be able to get a driver's license and a passport that will reflect her gender identity. She'll be able to travel without being hassled and apply to college as a girl.

As trans adults have moved from the margins of society into the public eye over the past few years, kids have begun to come out in increasing numbers and at younger ages. Although no agencies in Vermont are currently keeping statistics on numbers of trans youth, Dr. Rachel Inker from the Community Health Centers of Burlington's Transgender Clinic explains, "There are certainly more transmen and -women coming forward of all ages as transitioning becomes more acceptable and public."

Because schools and teachers across the state are dealing with more gender-nonconforming kids, the Vermont Agency of Education is currently collaborating with parents, staff from queer youth support and advocacy group Outright Vermont, educators and consultants to create a best practice guide relating to gender identity in school.

Two years ago Melissa Murray, the executive director of Outright Vermont, cofounded a Gender Creative kids social group for gender nonconforming children under the age of 13 and their parents. "Over the last five years or more, we've gotten calls from people asking us to work with youth younger than 13," Murray says. "We're finding more and more that youth ... are knowing their gender identity at earlier and earlier ages."

'She Insisted She Was a Girl'

Willow had yet to start preschool when she made an announcement: "As soon as she could talk," James explains, "she insisted she was a girl."

Dressed comfortably in a striped shirt with a bright pink flower and hot pink socks, on a snowy Saturday morning Willow talked animatedly about her self-discovery. Though she was born at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington, she and her family live in a small community in a more rural — and conservative— part of the state. Kids VT agreed to their request for anonymity to maintain their privacy.

Both James and his wife, "Elaine" are teachers. They recognized that Willow's determination was beyond typical childhood exploration, and so they consulted with experts at Boston Children's Hospital. The advice they got was to wait and see, and so they let Willow dress like a girl at home but sent her to school as a boy.

But her distress rapidly accelerated. "There were temper tantrums," James recalls. She would come home from school and rip off her boys clothing and put on whatever girls clothes were in the house. All they had were old costumes, so for nearly a year she wore a series of tiaras and a pair of fairy wings until they literally fell apart.

They waited to transition publicly in large part out of fear for her safety, but the wait-and-see approach seemed to be putting her in more danger, not less. As James explains, "little kids have no filter." Willow informed everybody at school that she was a girl, even going so far as to sneak a pair of her mother's high heels into kindergarten. Her peers didn't know what to make of her, teasing and harassing her. One day on the school bus, Willow talked about her ballet recital and a boy punched her in the face because "boys don't do ballet."

In 2014, James and Elaine attended a Boston Children's Hospital conference for gender nonconforming kids and their parents, where they interacted with other families in similar circumstances. After hearing the experiences of other families and talking to older teens who wished they'd been able to transition sooner, James and Elaine decided it was time. For her sake, Willow's "social transition" — publicly identifying as a girl — should happen sooner rather than later.

"We approached her transition like a political campaign," James explains, "one vote at a time." They enlisted Outright Vermont to train teachers and support staff at Willow's school; they reached out to individual parents and teachers; and they created video footage of Willow telling her story. Their goal was to cut through ideological resistance and get to the heart of Willow's hopes and needs.

In the video made for school staff, 7-year-old Willow grins at the camera in a purple sweatshirt with an orange flower barrette in her white-blonde hair. "Today is a very special day for me," she announces enthusiastically. "Because I get to express who I am! And if I can express who I am, then everyone will know, and then I am happy! And I think everyone else will be happy, too."

Willow vividly remembers the day, nearly a year and a half ago, when she was allowed to walk into first grade for the first time as a girl. "The day was June second," she recalls. She wore a flower-printed skirt, a tank top with a bow on it and pink high tops. Her parents turned the day into a celebration, showing up with a "birth cake" that announced in icing, "It's a girl!"

James also remembers that day well: the anxiety on the way to school in the morning and the profound sense of relief at the end of the day. "It was very, very freeing to have Willow transition and then have a positive response from the school and, for the most part from the community, and then to see a kid go from being depressed and anxious and all those things to being much more content and happy," he recalls. Willow still gets teased, although far less than before.

Meanwhile, James and Elaine have tried to prepare for the inevitable negative reactions — a remark in the grocery store or at the gas station — but a year and a half later no one has said a word. "You get a look every so often," James notes, "but they usually recover pretty quickly."

Both James and Elaine are very careful to be extra polite and pleasant as they go about their daily small-town lives. "They need to view us in a positive light so if things come up they'll say 'I might not agree with them, but that's an awfully nice family,'" James says. Although waging this daily PR war can be exhausting, James believes this is the way that social change happens. "People make decisions about this on a personal level," he explains. "Society progresses because you actually know a person."

Changing Data

Willow's family is charting its own course — in part because of a lack of data on transgender kids. No medical experts recommend medical interventions for prepubescent children. But parents of kids experiencing gender dysphoria — the feeling that your biological sex does not reflect your gender identity — can decide if and when their child should make a social transition, choosing to live publicly as their preferred sex.

The initial advice James and Elaine got from Boston Children's Hospital was based in part on a 1995 study, which indicated that 80 percent of gender nonconforming kids did not become transgender teens or adults

But best practice has changed over the past few years — and that study has been criticized because it didn't distinguish between children who expressed some cross-gender behavior and those who insisted they were another gender. Now mental health professionals recommend a social transition if kids are "insistent, persistent and consistent" in their belief that they are the opposite gender and if they show signs of distress.

Often the benefits of a social transition outweigh the risks, according to Christopher Janeway, a Burlington-based psychotherapist who specializes in gender identity. "It often is the case where there's more concern in a family if we don't listen to this child," he explained. "It's hurting their relationship, it's causing tremendous stress on the child and in the family." Janeway argues that parents need to let their child explore their gender identity even if there's a chance they might change their minds in the future.

"We can't know what's ahead for children if we're not supporting them where they're at," Janeway says.

Now past the social transition, Willow and her parents will face a whole new set of questions, challenges and bureaucratic hurdles when Willow reaches puberty. They'll have to decide as a family whether to put her on puberty blockers to halt the production of testosterone and prevent further sexual maturation, a treatment that is reversible. A few years later, they'll have to decide whether to administer estrogen, which has more permanent effects, including infertility. Finally, as an adult, it'll be up to Willow whether she wants to get surgery to remove her gonads and prevent testosterone production altogether.

Current medical practice gives kids plenty of opportunities to change their minds and make an educated and informed decision. It also aims to balance caution and urgency. Endocrinologist Dr. Martina Drawdy is creating a clinic at the UVM Children's Hospital for transgender teens, which will provide interdisciplinary, individualized care.

"It's important for treatment to be timely," Drawdy's resident, Dr. Jamie Mehringer, explains, "because ... we know that gender dysphoria is a life-threatening condition because of the very high rates of suicide, but at the same time we do think it's important to be cautious and make sure that we can confirm that this is the diagnosis that we're dealing with before starting treatment."

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health recommends beginning semi-reversible treatments like hormones around age 16 to reduce distress. Currently, the Endocrine Society is revising its guidelines to be more flexible with this age recommendation, acknowledging that there might be "compelling reasons" related to physical or emotional well-being to start cross-sex hormones earlier than 16. According to a study conducted by Gender Advocacy Training & Education, 94 percent of trans adults say that transitioning has improved their quality of life.

Soon there may be more data about gender development and mental health in transgender kids to help families make more informed decisions about transitioning. Willow's family is one of more than 150 across the U.S. and Canada being tracked over time as part of the University of Washington's TransYouth Project, the first major study of transgender children in the United States. Though the research is far from complete, Kristina Olson, the architect of the study, tentatively suggested in a recent Slate article that "many transgender-identified young children do in fact become transgender-identified teens and adults."

As Mehringer puts it "We know that as kids get older ... the longer the young person is having feelings of being the opposite gender or different gender, the more likely those are to persist."

The 'Dark Period'

Penny and Chuck Pizer had to make some difficult decisions when their 17-year-old son Marcus came out to them as transgender almost two years ago. Although Penny and Chuck were initially hesitant about starting testosterone treatment, they are now completely on board. "I think what convinced Penny and me," Chuck reflects, "was just watching Marcus and seeing the very different person that he became. He convinced us that it was real just by seeing the weight of the world taken off him ... the old soul of the person returned. We realized it was cruel to try and not proceed ... rapidly."

Penny agrees: "It's watching a soul that's trapped. And I keep telling myself it's just the packaging that changes; it really is the same person." Chuck chimes in and nudges Marcus, "And you're a pretty good-looking guy, by the way." Marcus gamely manages not to roll his eyes.

Although the Pizers live in a large house in South Burlington, they're all gathered into their front room, perched on overstuffed sofas while their tiny dogs scurry back and forth and intermittently hop up for a cuddle. Penny is a talkative and enthusiastic woman with chin length brown hair, while Chuck is quieter, with even longer grey curls. Marcus is lithe and athletic with short brown hair and a quiet, confident demeanor.

They're in the midst of a calm and peaceful period after years of turmoil and upheaval. Penny obliquely discusses the "dark, period" in their family, the years before Marcus came out to them, when he was angry and anxious and falling apart both at home and at school. "This doesn't come out pretty," Penny explains from her perch at the other end of the coffee table. "It usually shows itself in dark suicidal behavior, and you don't understand what's going on."

Marcus pipes up, "You're fighting your insides and your outsides and ... it's just a huge struggle, and you're angry and not understanding, so you're just lashing out."

Because things got so bad, Penny and Chuck were actually relieved when Marcus came out as trans, because they finally knew what was wrong. That said, they still had to grieve the child they thought they had. "Any parent has to come to terms," Chuck says. "There's a whole process from my standpoint from losing my little girl to gaining another son, but it was a journey that I had to take."

The Pizers, who have three adult children as well, have recently turned their house into a temporary home for transitioning kids called Safe Harbor for Trans Teens. They believe that in some situations trans kids and parents need a separation from each other. "There needs to be a time out for families where everybody can kind of come to grips with what's going on," Penny explains. The Pizers' goal is to turn the "hell they went through as a family" into a positive experience for others in their situation.

Although many of the emotional hurdles have been surmounted, Marcus still has a long list of bureaucratic and logistical hurdles: surgery to remove his breasts, insurance coverage and countless name-change forms. But he's already cleared a bunch: starting testosterone, coming out at home and at school, picking a new name.

After three months on testosterone, Marcus' life and his body are beginning to take on the shape he wants. "My voice is changing," he says enthusiastically. "I'm getting an Adam's apple. My shoulders have broadened ... just a lot of fun changes."

That said, going through puberty for the second time is not all fun and games. His mother laughs and says, "We literally watch Marcus every week go one year up. So we went through sixth grade humor, seventh grade humor, farting and belching at the table. I think we're up to 15, 16 now, thank God."

The Parents' Process

Willow loves coming to Burlington for Outright Vermont's Gender Creative Kids social group because she feels more comfortable around other trans kids. "My body is more relaxed," she reflects. "I can actually talk about it and not have to explain."

But the parents who attend the monthly gathering for trans and gender creative kids — kids who don't identify as either male or female — need it just as much as their children do.

Christopher Janeway, who runs the Outright support group for parents of trans teens with Outright director of education Dana Kaplan, says it's important to create a safe space where parents can voice their complicated feelings — which run the gamut from sadness to anger, guilt to shame — so as not to burden their kids.

"Often in their homes they're trying very hard to adjust to new pronouns and new names, and [at the support group] they just have a space where they can release some of their frustrations around that process of change," he explains.

On a Sunday in early December, parents in the Gender Creative Kids group compare painful stories about insensitive relatives over Thanksgiving and seek out advice about transitions and bathrooms. One mom new to Burlington wants to help her transgender daughter come out in second grade. Although "Elsa" was assigned male at birth, she started school this year as a girl. But she's tired of carrying around a secret. Elsa wants her peers to know her story, but she's afraid if she comes out she'll lose friends and be teased.

Another set of parents, attending the support group for the first time, are desperately seeking help for their emotionally distraught transgender middle schooler. The school is being supportive, but they don't know what to do about the bus, the hallways, the interstitial spaces where bullying thrives. "And the bathroom situation is tough," the mom continues, describing a panicky night out at a theater trying to figure out which bathroom their daughter could safely use. The other parents nod knowingly, weary veterans of the public bathroom wars. Some suggest books and resources, and others offer playdates with their children.

The newcomer mom looks a bit relieved, but when the conversation turns to pronouns, her face falls. "This week he said 'I'd like to be called she,' but it doesn't come out," she says. "It's so new it doesn't come out of my mouth yet."

"It will," James reassures from across the table, and other parents nod in agreement.

Janeway says that parents of transgender kids may experience all the stages of grief, including the "bargaining" period during which they wonder what they could have done differently. But moving through this process can ultimately lead to acceptance — and even deep appreciation for what they've learned from their children.

Willow's mom, Elaine, says of her journey, "You have a baby, and you instantly start dreaming about what their life is going to be like ... and then you have to change those dreams."

Calling it "an extremely reflective time," Penny Pizer likened the experience to being "brought to your knees and ... up again."

Willow's and Marcus's families have healed and rebuilt in part by turning toward activism and advocacy. The Pizers have already taken in their first trans kid, and James is working with the Agency of Education on their gender-identity guide.

"I'm inspired by it," Chuck Pizer reflects softly. "It's forced me in a lot of ways to walk policies and philosophies that I've talked about for a long time ... It's made me a better person."

Resource List

- Transgender FAQ

- Safe Harbor for Trans Teens: An organization for trans youth in need of a temporary home. Follow it on Twitter

- Outright Vermont Gender Creative Kids Group: A social group for kids under 13 and their parents and caregivers.

- Outright Vermont Trans Group: Open to 13- to 22-year-olds are who are trans identified, nonbinary, gender nonconforming or questioning their gender identity and looking for a space to be in community with others who share this identity.

- Outright Vermont Trans Parent Group: Support group for adult family members of trans, gender queer, gender nonconforming or gender creative youth.

- Outright Vermont Friday Night Group: Social and support group for self-identified queer youth, ages 13-22.

- TransYouth Family Allies: A comprehensive list of resources for families with trans children.

- Community Health Center of Burlington Transgender Clinic

- The University of Vermont Children's Hospital Transgender Resources Guide

This article was originally published in Seven Days' monthly parenting magazine, Kids VT.

More By This Author

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of...

-

Taking Refuge: Transgender Newcomers Find Safety, Services and Community in Vermont

Nov 22, 2023 -

Champlain Valley School District Spells Out the Rights of Transgender and Nonbinary Students

Oct 25, 2023 -

Q&A: Meet a Married Couple Who Are Wild for Barbie

Aug 2, 2023 -

Video: Peter Harrigan Collected 600 Barbie Dolls in 30 Years, With Support From His Husband, Stan Baker, Who Collects Ken Dolls

Jul 27, 2023 -

UVM Student Wins Inaugural Nonbinary Division at Boston Marathon

Apr 26, 2023 - More »

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.