Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Burlington Punk Club 242 Main at 30

Published January 28, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 8, 2020 at 4:59 p.m.

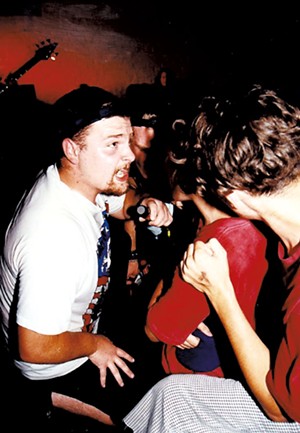

Tricky Nicky of Jumanji X's Riot Squad stands on the far side of the stage at 242 Main in Burlington, his sunburst guitar slung low as he fiddles with knobs on his buzzing amp. He strums a chunky chord and, satisfied with its distorted crunch, turns and nods to his band's lead singer, a string-bean teenager named Ethan. Ethan swipes a sweaty tangle of hair from his eyes and holds the mic close to his face with two hands.

"You guys should probably mosh to this one," he says.

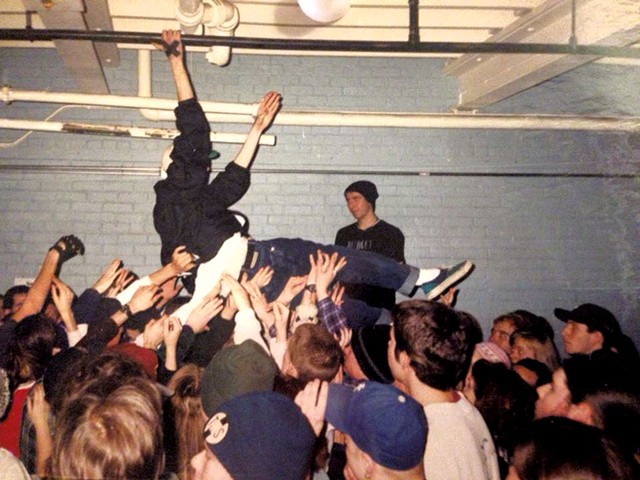

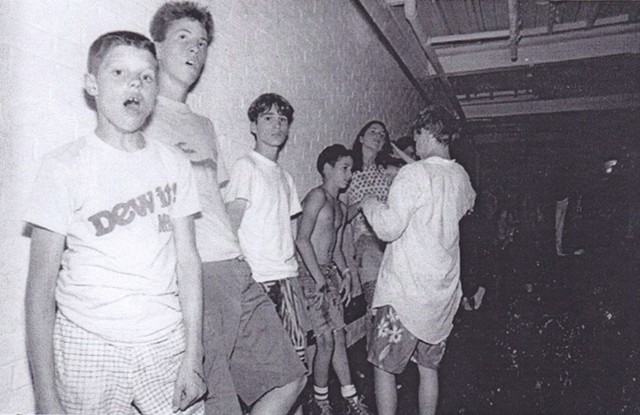

Ethan cocks his head back and brings the entirety of his gangly body violently forward. Taking his cue, the high school punk band from Woodstock launches into a frenetic, Misfits-style punk anthem. And the crowd of kids at 242 is all too happy to oblige Ethan's request. The concrete floor in front of the stage becomes a cyclone of knees and elbows.

It's been a while since this thirtysomething has set foot in 242 Main for a punk show. But the scene looks and feels almost exactly as I remember it from my teenage years, as it likely would to anyone who's spent time there since the venue opened in the mid-1980s.

In the pit, a guy is creating a windmill of fists to clear out space amid the madness. There's always a guy in the pit doing that. Just like there's always some oversize lug lumbering around the edges, looking for somebody smaller to push, as there is now. Those who don't want to get drawn into the fray — or trampled by it — form a loose circle around the mosh pit. Some step back when a wayward slam dancer careens out of orbit. Others, perhaps more accustomed to the delicate intricacies of pit etiquette, shove strays back into the swirling mass.

In my time at 242, I don't recall ever seeing signs prohibiting stage diving like the ones that now hang on either side of the stage. They may well have been there in my day and been patently ignored. I remember the place being dingier, with walls closer to colorless than the bloodred hue that now shades the room. Today's lighting rig is certainly fancier. New, too, is the almost parental dread gnawing my gut as I watch the crazed pit from a safe (read: lame) distance, certain some poor kid is gonna get hurt.

But then the lumbering lug lends a hand to a fallen girl, helping pick her skinny frame up off the concrete before she's stomped on. She pats his shoulder and gleefully throws herself back into the pit — and I remember that mosh pits, for all their ferocity, can be intimate, communal places. When a kid with handmade patches on the back of his jacket brushes past me, my nostrils sting with a familiar scent: the sharp tang of sweaty punk. It smells like ... well, teen spirit. And to any of the kids who have called the place a second home over the years, it smells like 242 Main.

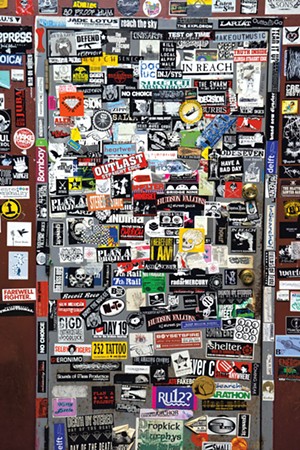

Scenes like this one, on a frigid Saturday night in January 2015, have played out innumerable times since 242 Main first opened as a teen center in the bowels of Memorial Auditorium. A thousand bands have played on that stage. Some musicians and fans may have worn longer Mohawks back in the day than the close-cropped version Tricky Nicky now sports. And instead of his black Vandals tee, previous generations would have worn the tattered cloth of Bad Religion, the Ramones or Earth Crisis.

Many of the kids undoubtedly also wore black Xs on the backs of their hands — the "straight edge" symbol referring to a subset of punkers who abstain from drugs and alcohol. A zillion righteous sermons about unity and social politics have been preached from 242's stage, such as the one the lead singer of Rutland hardcore band Get a Grip delivers on this night. The faces have changed at 242 Main, but much remains the same.

Approaching its 30th year, 242 Main is believed to be the oldest all-ages, substance-free punk club in the country, narrowly edging out 924 Gilman Street, the all-ages punk mecca in Berkeley, Calif., which opened on December 31, 1986. Almost certainly, Burlington's is also the only such club owned and operated municipally; 242 is owned by the City of Burlington and operated by the Department of Parks and Recreation.

Even locals who don't know 242 Main has those national distinctions know it as the epicenter of hardcore punk culture in Vermont. Since the Reagan administration, it has served as a safe haven for youth who might not otherwise have had one. It's been a musical breeding ground, a starting point for generations of Vermont rockers, punk and otherwise. Many of them have gone on to make music their lives — and livelihoods.

But 242 Main didn't always smell like sweaty punks. In fact, when it first opened, it usually smelled like hazelnut coffee and chocolate-chip cookies.

Sorting out a precise history of 242 Main is tricky at best — and a fool's errand at worst. Very little about the club has been physically documented or catalogued over the years, so its stories exist mostly in the memories of those who were there. And their recollections vary, sometimes wildly.

For example, popular wisdom holds that 242 Main opened its doors as a teen center in 1985, which would make 2015 the club's 30th anniversary. Indeed, programming in the name of that milestone has been ongoing since October 2014, when famed hardcore punk band Bane played the club to celebrate the birthday.

The problem?

"242 Main opened in March of 1986," says Jane Sanders in a recent phone call.

So there's that.

Everyone agrees on one point regarding the origins of 242 Main, though: that Sanders (then Jane Driscoll), along with Kathy Lawrence, was instrumental in the club's formation and in the vibrancy of its earliest incarnation. Sanders is now the wife of Vermont's junior United States senator, Bernie Sanders, who was mayor of Burlington from 1981 to 1989. As Jane Driscoll, she directed the Mayor's Youth Office, a now-defunct council created in 1984 to give local youth a voice in city politics. While it was nice for the kids to have a guest room in city hall, Jane Sanders says now that what they really wanted was a place to call their own.

"We all agreed we needed to find a fresh space for them," she recalls, noting that teens would frequently climb in through the window of her city hall office seeking an audience.

An interesting side note: In the summer of 1981, at the beginning of Sanders' administration, Driscoll and Lawrence had tried to present a rock concert at Battery Park in Burlington. They discovered the city had an ordinance prohibiting the performance of rock music on public property, enacted under previous mayor Gordon Paquette. So Driscoll and Lawrence petitioned the city to have the ban lifted, and Bernie obliged on a temporary, provisional basis.

Seeing that Queen City children had not turned into devil-worshipping hellions after the concert, Sanders permanently removed the ordinance in time for a battle of the bands at Memorial Auditorium that November. "It was funny, because Bernie is not a great fan of rock music," says Jane Sanders.

Maybe not, but he may just be Burlington's rock-and-roll savior. 242 Main couldn't have existed without the removal of that Footloose-style ban.

Around the same time the youth office was born, the city's water department vacated its offices in the southwest corner of Memorial Auditorium's basement. Driscoll identified the space as an ideal spot for a teen center.

"It didn't seem big enough for the city to use otherwise," Sanders says now. She approached the board of aldermen — a precursor to the current city council — on behalf of the Mayor's Youth Office, starting the process of gaining city approval to retrofit and repurpose the space. With a $60,000 Community Development Block Grant in hand, Driscoll began the work of building 242 Main as a city-run teen center in 1985.

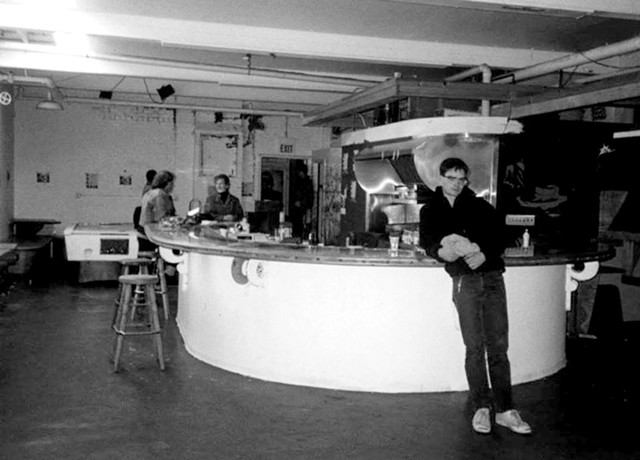

"We relied on a lot of support within the community," Sanders says. She credits Vermont architect David Sellers and designer Ed Owre in particular with helping to shape the physical space — with significant input from local kids themselves. Some teens actually helped construct the club as part of a building class.

"It was extraordinary how they rebuilt this dark, dank space into a fantastic place," Sanders says.

When it opened, 242 Main had a full stage that could double as a seating area when it wasn't being used for music. Rock shows happened on most weekend nights, often featuring local bands such as Screaming Broccoli and the Hollywood Indians. Occasionally bigger bands would drop by, too, including punk legends Operation Ivy and Fugazi.

During the week, the space served a greater variety of purposes. It hosted daily after-school programs for Edmunds Middle School kids staffed by area high school students. There was a weekly lecture series for high schoolers on civic responsibility, featuring guest speakers from the community. 242 was a rehearsal space for plays. It was a production space for a biweekly newspaper produced by local kids, the Queen City Special. A triweekly local-access TV show called "242 Presents" was filmed there. The place had a full-service lunch counter staffed by teens slinging burgers and fries.

For a time, 242 Main even offered an acoustic-music brunch on Sunday mornings. And most afternoons, the smell of fresh-baked cookies and hazelnut coffee filled the space between walls adorned with artwork and colorful murals.

Sanders says the heart and soul of 242 Main in the 1980s and early '90s wasn't burgers or art projects. It wasn't even punk rock. It was that the space belonged to the kids who used it, and they — not parents or politicians — could make of it anything they wished.

"There was a sense of community. The younger kids learned from the older kids. The older kids took responsibility and learned to be role models and mentors," Sanders explains. "There was a sense of purpose among the kids, and they determined what that purpose was.

"At the time, it seemed people were always saying, 'We have to deal with truancy, drug abuse, problems with kids,'" she continues. "We were adamant that we wanted to deal with the whole person and provide an outlet for their interests and abilities that was not about what was wrong with them, but what was unique about them."

Lawrence, who worked in local correctional centers before she began managing 242 Main, agrees.

"Prevention has more to do with developing and encouraging people's passion early on," she says.

That, and checking the mail.

Lawrence, speaking from the Burlington clothing boutique Common Threads, which she owns, says she almost never encountered behavioral problems with the kids at 242 Main. Visitors, however, could be a different story.

For example, there was the time a Canadian band asked to ship merch to Burlington ahead of their tour stop at 242. Lawrence suggested the band send it to her house in case no one was at the teen center to receive it. The package arrived safe and sound on her doorstep ... accompanied by an FBI agent.

"There were drugs in with the T-shirts," she recalls, chuckling.

Then there was the storied night she escorted GG Allin out of the club for, well, being GG Allin. The notorious punk singer, who grew up in Vermont and is now deceased, showed up and reportedly hurled a contraband bottle of Jack Daniel's at the Wards during their set.

"Oh, yeah. I kind of remember that," says Lawrence.

But by and large, she says, the kids who hung out at 242 Main treated her, and the space, with respect. That's probably because she showed them the same.

"We all loved Kathy," says Richard Bailey, who started going to 242 Main in 1986. A local musician best known for his time in the 1990s funk-rock band DysFunkShun, he currently plays in the punkabilly band Swillbillie. Bailey helped run 242 Main for several years in the early to mid-2000s and now manages Memorial Auditorium. In that role, he still helps oversee the club, albeit in a less hands-on fashion.

Lawrence says she gradually began extricating herself from 242 Main in the early 1990s. Around that time, the Mayor's Youth Office was dissolved by Bernie Sanders' successor, Mayor Peter Clavelle, and the vitality of the teen center subsequently waned.

Burlington City Arts absorbed 242 Main, but Bailey says it was never an ideal fit. Much like the population of kids it served — by then mostly punk rockers — 242 Main became something of a misfit within city government.

"BCA tried things like photography classes," Bailey says, speaking from his Memorial Auditorium office. "But 242 isn't a darkroom, it's just a dark room."

And then it just went dark.

In 1998, during his second stint as Burlington's mayor, Clavelle briefly closed 242 Main. After an outcry of public support convinced him to reconsider, management of the club was transferred to the Department of Parks and Recreation. Simon Brody, who had been helping book shows at the club since the early '90s, assumed a larger role in funneling bands to the space.

"When I came in, there was minimal funding or effort devoted to 242," Brody says by phone. Once the lead singer of famed Burlington hardcore band Drowningman, he is now a lawyer in Kansas. "The occasional punk band would play there on the weekend, but there really wasn't much going on."

Brody says he made a concerted effort to tap into and nurture the club's punk roots. It worked. 242 Main resurged, and some of the club's most memorable shows happened during Brody's tenure — including Black Flag, Converge, Dillinger Escape Plan and Piebald. The late '90s were also a particularly fertile era for local hardcore and punk bands.

Another factor in 242 Main's renaissance was the closure of Burlington nightspot Club Toast on December 31, 1998. Brody had worked at that club and leaned on its owners, Dennis and Justin Wygmans, for booking connections with bigger hardcore, punk and ska bands.

"There really wasn't another place in town to have those kinds of shows," explains Brody. He notes that the Wygmans brothers donated the Club Toast sound system to 242 Main. It's still in use to this day.

By his own admission, Brody's time at 242 Main, which ended in 2002, was often uneasy.

"I say things, which isn't always in my best interest," he concedes, and explains that he and the city didn't always see eye to eye on how best to use the space.

"The city wanted to run more programs there," says Brody, who himself took classes at 242 during Lawrence's tenure. "But I didn't think it should be this mainstream kind of place. To me it was always kind of counterculture."

In 2000, Bailey assumed the role of dealing with the city on a part-time basis, while Brody focused primarily on booking bands. Among the most successful programs birthed under Bailey, who became a full-time employee in 2001, was the weeklong Summer Rock Music Camp started by local musician Greg Matses. Matses had run the day camp previously in other locations before it found a home at 242 Main in 2002. It continues to flourish there.

In the years since, the club's popularity has ebbed and flowed — much as it always has. Following Brody and Bailey, a string of staffers have overseen the place, few lasting more than a year or two.

"It's probably in a bit of a down cycle right now," concedes Justin Gonyea, speaking about the current state of 242 Main by phone. Gonyea is the club's current booking agent, a role he inherited this year from local musician Tyler Daniel Bean, who held the post for two years. He works hand in hand with Jen Cotton, the site director for both 242 Main and Memorial Auditorium under Parks and Rec.

Gonyea grew up in New Hampshire and moved to Burlington in 2010. Immediately drawn to 242 Main, he became involved in its music scene (he's a member of Doom Service) while helping to book shows through his connections as the owner of independent punk and hardcore label Get Stoked! Records.

"I wish I'd had a space like 242 Main growing up," Gonyea says. "I lived in Boston for 10 years, too, and I think people there would kill for an all-ages space like 242. I think people who grew up here with it take for granted how awesome a space it really is, and how incredible it is that it's lasted this long. Because a lot of these kinds of places don't."

Ryan Krushenick grew up in Vermont, but he doesn't take 242 for granted. The club prepared him for his former role as lead singer of the hardcore punk band Unrestrained, one of the most notable Vermont bands to call 242 Main home in recent years.

Now 29, Krushenick has been going to the teen center since he was in eighth grade, when a school guidance counselor turned him on to the Wards — generally regarded as the first Vermont punk band. That discovery led him to message boards at the Big Heavy World website, where he found postings about punk shows at the club. And he went.

"Up until that point, my outlook on my community was that I was an outsider that didn't belong anywhere," Krushenick says. "I had a pink Mohawk; I wore crazy clothes. I was viewed as a freak. It was the first time I walked into a room full of people I didn't know and I wasn't a social leper. I was hooked."

He started playing drums shortly thereafter and began hanging out at 242 Main.

"It didn't matter if we'd even heard of the band," he says. "If it was a punk, hardcore or ska show, we got there however we could."

Krushenick believes he's played as many shows at 242 Main in the past 12 years as anyone in Vermont, if not more — whether with his first band, Cheat to Win, or his later groups, My Revenge and Unrestrained.

"That was and is the place to play," he says. "It felt both punk rock and underground, but real-world and professional. To be able to do that as a 15-year-old changed my life."

With My Revenge and Unrestrained, Krushenick has toured all over North America, Central America and Europe, and has seen his records distributed just as widely. But 242 remains home.

"We could play anywhere in the world, but playing 242 Main was always special," he says. "242 Main is the CBGB of Vermont."

He's not the only one to suggest that. Jane Sanders draws the same parallel to the iconic New York City punk club when asked about the teen center's direction since she left.

"It's really more like CBGB for young people," she concedes.

Though CBGB was a bar and most decidedly not an all-ages teen center, the comparison isn't entirely inaccurate. And it has troubling implications. After all, even the great CBGB closed. Given the uncertainty surrounding the future of Memorial Auditorium, some locals wonder how many anniversaries 242 Main has left.

"That's the big question," says Bailey. He cites a laundry list of renovations the nearly 90-year-old building requires to remain viable — everything from cosmetic face-lifts to a new heating system. "And no one really knows," he adds.

Jesse Bridges, director of Burlington Parks and Rec, can't say what the future of Memorial Auditorium might be. He does reveal that the city recently completed an assessment of that facility and others around town, whose findings will be released in time for Town Meeting Day in March. Bridges describes the building generally as "multipurpose without a purpose," adding that it "doesn't make enough money to pay the bills."

He notes that Parks and Rec does see value in the niche 242 Main fills, particularly in the relation to the city's other youth-directed efforts.

"It's an evolving and fluid program," Bridges says. "We're trying to have more conversations around that and talk about what are the needs for the community, specifically teen programming. That will be important in determining what needs to happen going forward."

Then Bridges poses a question that might be difficult for some veterans of 242 to consider.

"Is 242 tied to 242 Main, or is it tied to the idea and concept around a kind of open space that can be whatever?" he asks. "Because if it's just music, there are lots of other places that could go."

But many would argue that 242 Main is about more than just music.

"It would be hard to imagine what my life would be like without 242," says Krushenick. "The most important people in my life, I met at 242."

He credits Bailey with saving the club from "kids playing Ping-Pong after school," and with preserving the space as a punk haven through dark times. For his part, Bailey acknowledges the uncertainty surrounding Memorial and 242 Main. But he suggests its spirit could live on, even in another venue.

"It might be that someday 242 Main will have to reappear in some other form somewhere else," he says. "But that doesn't necessarily have to be a bad thing." Bailey adds that, if the club has to move, the city might do well to take a cue from Jane Sanders.

"It might be an opportunity for kids themselves to decide what they really want out of a space like that," he says, "which is really what it was always meant to be."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Urban Legend"

Related Locations

-

242 Main

- 242 Main St., Burlington Burlington VT 05401

- 44.47625;-73.20977

-

802-862-2244

802-862-2244

- www.242main.org

-

(based on 1 user review)

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Music Feature, Music, punk, mosh, 252 main, hardcore punk, punk music, 242 Main

More By This Author

About The Author

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

About the Artist

Matthew Thorsen

Bio:

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Matthew Thorsen was a photographer for Seven Days 1995-2018. Read all about his life and work here.

Speaking of...

-

Two Local Band Directors March in the Macy's Parade

Nov 22, 2023 -

Before a Burlington Show, the Wood Brothers Get Back to Basics

Oct 26, 2023 -

After a Half-Century of Leading Local Ensembles, Steven and Kathy Light Prepare a Musical Farewell

May 3, 2023 -

Double E 2023 Summer Concert Series Kicks Off With the Wailers

Mar 17, 2023 -

Soundbites: The Last of Jim's Basement

Mar 15, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. On the Beat: maari Drops 'Eyes Wide Shut,' and a Farewell Show for Pete Sutherland Music News + Views

- 2. Soundbites: Umphrey's McGee Loves Burlington Music News + Views

- 3. Frankie White, 'brain dead' Album Review

- 4. Community Garden, 'Me vs Me' Album Review

- 5. River City Rebels, 'Pop Culture Baby' Album Review

- 6. Waking Windows Announces 2024 Lineup Music News + Views

- 7. On the Beat: Vermont Native Adam Tendler Returns, New Music From Jesse Taylor Band and Justin Levinson Music News + Views

- 1. Lily Seabird, 'Alas,' Album Review

- 2. Legendary Vermont Saxophonist Joe Moore Dies Music News + Views

- 3. Soundbites: Trouble & Together at the Flynn Music News + Views

- 4. Soundbites: Surf's Up With TEKE::TEKE Music News + Views