click to enlarge

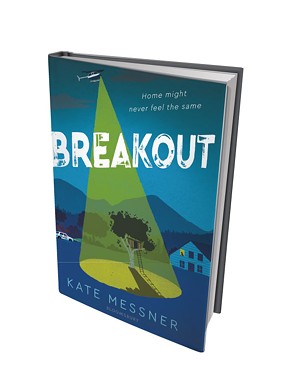

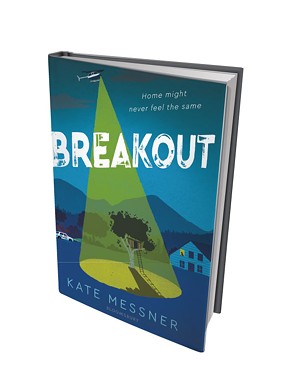

When Nora Tucker, a seventh grader at Wolf Creek Middle School, begins her summer vacation by compiling students' submissions to a community time-capsule project, she expects it'll be filled with essays about the usual summertime fare: swimming in the creek, marching in the Fourth of July parade and competing in the annual Mad Mile foot race.

But when two inmates escape from the town's maximum-security prison, where Nora's father works as superintendent, her previously quiet hometown turns into an armed fortress, besieged by search parties, police roadblocks and helicopters circling ominously overhead. Meanwhile, Wolf Creek's local market is inundated with national reporters, as well as inmates' out-of-town families who can't visit their loved ones, now under 24-hour lockdown.

As the search for the escapees unfolds, Nora and her friends confront some difficult realities about race, white privilege and the previously invisible lives of the prison inmates.

In Breakout, a middle-grade novel for readers ages 9 to 14, Plattsburgh, N.Y., author Kate Messner has once again tackled a challenging subject with creativity, sensitivity and tact. Like her previous novels — 2017's The Exact Location of Home, which addresses a family's homelessness, and 2016's The Seventh Wish, which discusses heroin addiction — Breakout is a good conversation starter for discussing race, social justice and mass incarceration.

As Messner explained in a recent interview, Breakout was inspired by real-life events that, for her, hit dangerously close to home. In June 2015, two inmates serving life sentences for murder escaped from the Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora, N.Y., just 14 miles from Messner's home.

Messner, who spent seven years working in broadcast journalism before becoming a schoolteacher and, later, a full-time author, was immediately captivated by the drama unfolding around her.

"I never quite got over journalism," she said. "So when something this big is happening, I still have a very strong pull to be in the middle of it."

On the third day of the search, Messner heard about a press conference at the prison, so she grabbed her reporter's notebook and went. At the time, she said, she wasn't planning to write a children's book about a prison break — "because that's a weird idea," she said. "Who does that?" But she trusted her journalistic instinct for a compelling story.

click to enlarge

- Breakout by Kate Messner, Bloomsbury Children's Books, 448 pages. $17.99.

Later, Messner spent two days hanging out in Dannemora's Maggy Marketplace-Pharmacy, a convenience store and coffee shop across the road from the prison. Because it's the only place in town to get lunch, Messner explained, everyone showed up there: journalists, police who were covered in ticks and mud from the search, and neighbors whose kids were too frightened to sleep at night. Messner also heard stories from inmates' relatives who'd come to visit, only to be turned away because the prison was locked down.

"They were terrified about how their loved ones would be treated on the inside as this was all going on," she said.

Soon, Messner saw this story-behind-the-story as an intriguing premise for a book: How would such an event change the way people thought of their neighbors, their home and their town's largest employer?

Initially, Messner wrote the novel entirely from the perspective of Nora, whose black-and-white notion of her father as "one of the good guys" is suddenly upended when she befriends Elidee Jones, an African American girl whose family just moved to predominantly white Wolf Creek from New York City to be closer to Elidee's incarcerated brother.

But when Messner's writer friends critiqued her first draft, she said, their comments shared a common theme: They wanted to hear more from other characters such as Elidee.

To add their voices, Messner used an unconventional storytelling device — what she called "a novel of documents" composed of students' letters, poems, texts, comics, photos and transcribed conversations submitted for the time capsule. Together, they create a patchwork of experiences and perspectives.

"Once I started doing that," Messner added, "I knew it was a much more powerful approach to this story."

Thus far, Breakout has been greeted with critical enthusiasm. Even more importantly to Messner, the book has attracted the interest of educators who aren't afraid to tackle its challenging subject matter with their students.

Among them is Melissa Guerrette, a fifth-grade teacher at Oxford Elementary School, in Oxford, Maine. The Saint Michael's College graduate is a self-described fan of Messner's books. She helped raise $16,000 to purchase 1,500 copies of The Seventh Wish and distribute them to her district's schools and libraries. For the last four years, The Seventh Wish has also been part of Oxford Elementary School's health curriculum.

Reached by phone, Guerrette said she now has a small group of fifth graders reading and discussing Breakout, too. Oxford, like Wolf Creek, is predominantly white, she said, so the book has sparked "some pretty humbling and reflective conversations." Her reading group includes a biracial student whose father is employed in corrections.

"For my students, Breakout allowed them the opportunity to explore the idea of privilege and racism in a way that was safe," Guerrette added. "It was distant enough that they could talk openly and ask questions and wrestle with some pretty uncomfortable ideas."

Messner's books haven't always been as well received by educators and librarians. In June 2016, South Burlington's Chamberlin School canceled her scheduled reading of The Seventh Wish because of the book's openness about heroin use. The librarian at another school refused to carry the book because, as she told Messner, "Our families don't deal with things like that."

But Messner said she regularly receives emails from kids who say otherwise.

"One girl who wrote me said that, while she was reading the book, her cousin died of an overdose, and it helped her feel not alone," she noted.

Messner hopes that Breakout plays a similar role in helping kids better understand the role of race and privilege in mass incarceration. As she put it, "It's not a book to read with your family if you don't want to talk about these things."