Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Redacted: How the City of Burlington Keeps the Public in the Dark

Published March 4, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated March 11, 2020 at 10:44 a.m.

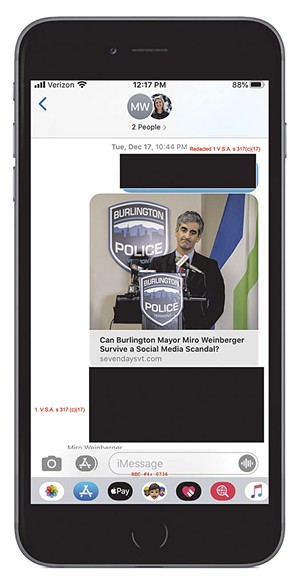

click to enlarge

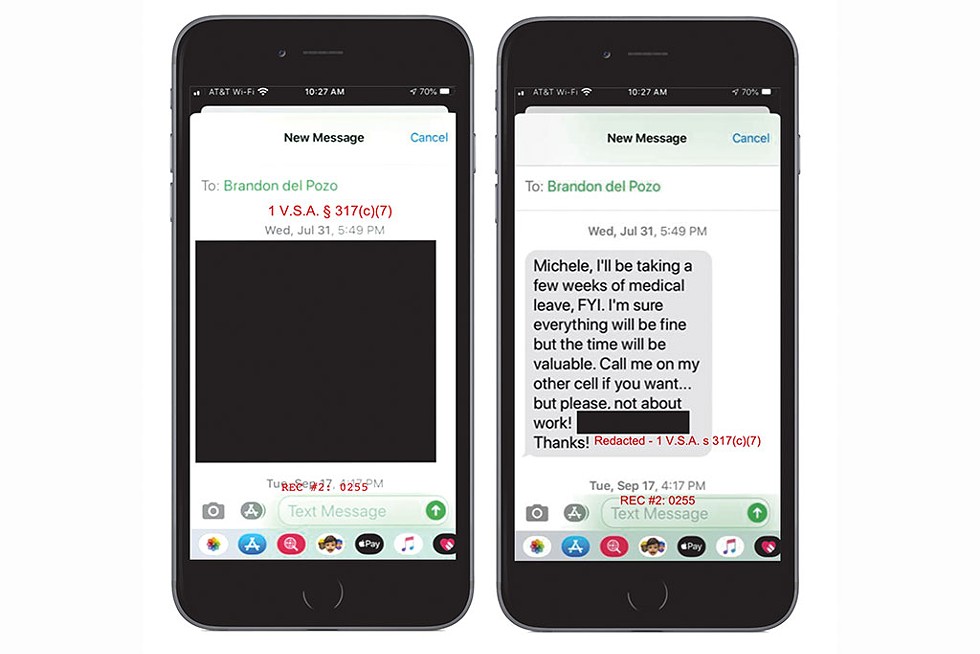

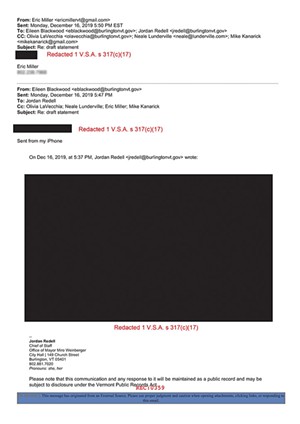

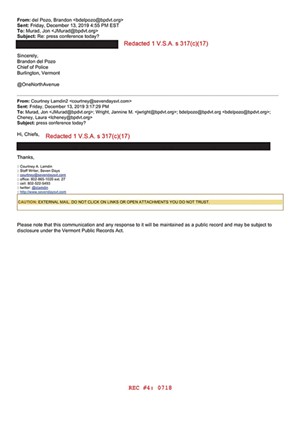

- Burlington initially redacted this text message Brandon del Pozo sent to a Burlington Police Commission member. The city released it after an appeal.

The social media scandal that erupted in December and prompted two Burlington Police Department leaders to resign made it clear that the department had a serious problem. But just how big a problem?

Did police officials know that top cop Brandon del Pozo had used an anonymous Twitter account to harass a critic? And why did deputy chief Jan Wright, who admitted to using a pseudonym online to defend the department and denigrate citizens, resort to these tactics? Was it just personal sniping, or did Queen City police officers use social media to monitor dissidents and try to steer conversations in public spaces?

Just how deep did this scandal go?

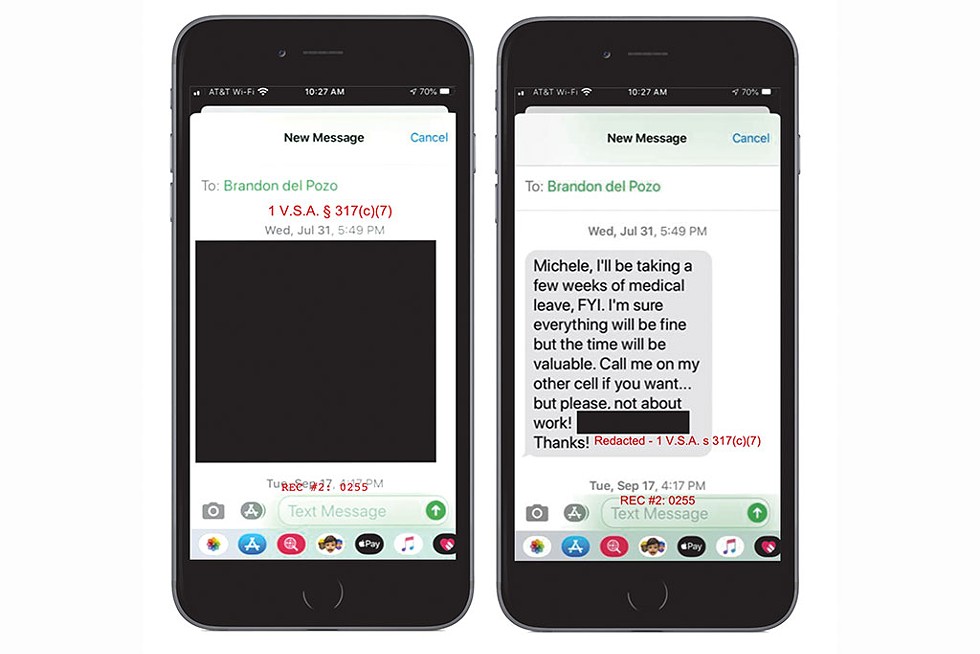

In search of answers, Seven Days filed an extensive public records request on December 18.

After the newspaper paid nearly $1,000 in fees to the city and waited more than two months, Burlington delivered 3,100 pages of emails, text messages and social media posts from Mayor Miro Weinberger and his staff, police commissioners, and the former chiefs.

But while the documents turned over were voluminous, they were generally not revealing. City attorneys invoked exemptions to Vermont's Public Records Act nearly 1,000 times to justify withholding information on documents, including ones created on key dates related to the scandal. Sometimes the city blacked out a line or two; in many instances, the city's attorneys obscured swaths of text. Often, their redactions spanned several pages.

Most of the documents the city did release in full were innocuous: newsletters, Front Porch Forum posts and lengthy email attachments of previously published material.

Much of the withheld information was shielded by a claim of "interdepartmental communication" — a so-called "deliberative" clause that is one of many exemptions to the Vermont public records law that First Amendment advocates say is often abused.

The document cache did reveal that city attorneys are eager redactors, concealing in some cases the most mundane messages and documents. They withheld the minutes from public meetings that had already been posted on the city website. They blacked out a request from one police commissioner to another to "please resend the proposed agenda" for a meeting. They redacted an email sent by the Seven Days reporter who made the records request.

Seven Days obtained complete versions of some documents by appealing to the mayor to undo his attorneys' edits and by simply asking people on the email chains to share the complete messages.

"Weird," said Andrea Todd, a city resident whose email exchanges with the Burlington Police Commission last fall were partially withheld. "Why would they do that?" Todd asked. "Why would they delete these things that are actually showing action on my request?"

The city's responses make it difficult to determine whether officials declined to turn over important information about the scandal. And absent informative records and reports, Burlingtonians must now rely on the mayor's word to judge how he handled the crisis.

Weinberger has faced criticism because he knew in July what del Pozo had done but didn't reveal it until months later, when Seven Days asked him about it directly. Weinberger has said he wanted to protect the chief's privacy since del Pozo's actions were related to an underlying medical issue.

The mayor has also consistently defended the city's record on transparency and said the scandal was a uniquely complicated situation. In an interview last month, Weinberger argued that he should be allowed to have candid discussions over email without any concern that they would become public, and he noted that judges have sided with the city in past records cases.

He asserted that his administration has handled the situation properly. A city-led investigation into Wright, which revealed that she and del Pozo knew about each other's social media misconduct, found no evidence of collusion or a wider conspiracy, the mayor said. He considers the matter closed, though residents and some city councilors have called for an impartial outside investigation.

First Amendment advocates who reviewed the records that Seven Days received said city officials seem to value their right to withhold over the public's right to know at a time when they should be working to regain trust.

Burlington's "redact first, ask questions later" approach "doesn't give a lot of faith to the public that these redactions are being applied appropriately," said Jay Diaz, a staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union of Vermont.

"Municipalities can do these redactions, but [the law] doesn't require them," he added. "The more they hide this information, the guiltier they look."

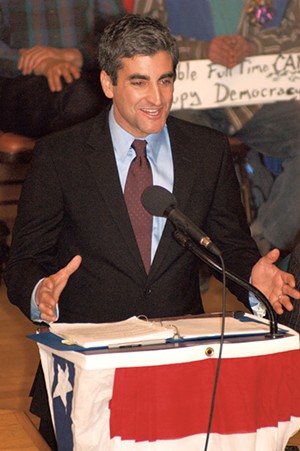

Transparency Mayor?

In 2012, Weinberger kicked off his first mayoral campaign with a pledge to restore trust in city hall. In a candidate debate on transparency, he promised he would hand over sensitive records because "the cover-up is often worse than the crime."

"To come clean would make sense," he said during a debate at the time.

Queen City residents were still reeling from the imbroglio that felled the previous mayor, Bob Kiss. The Progressive pol left office amid allegations that he secretly spent millions in city funds to bail out Burlington Telecom in 2009.

Weinberger, a Democrat, capitalized on it. At door-knocks, he promised to get Burlington's books in order. He painted his Republican opponent, Kurt Wright, as a Kiss sympathizer. He printed up stickers with the slogan "Miro for Mayor: A Fresh Start."

Burlington resident Charles Winkleman was sold. His then-roommate worked for Weinberger's campaign and convinced Winkleman, a recent college grad, to caucus for the mayoral hopeful and volunteer at an evening phone bank.

"It was gonna be a new administration with transparency and honesty," Winkleman said. "I believed him. Why wouldn't I?"

Roughly eight years later, Winkleman was at the center of the police department's social media controversy. Del Pozo created the Twitter account @WinkleWatchers to troll Winkleman, who was no fan of the former chief's and has become one of Weinberger's most vocal detractors.

"You can't be transparent if you never acknowledge you've done something wrong," said Winkleman, an affordable housing advocate and former chair of the Progressive Party in Burlington. "From when I first volunteered on [Weinberger's] campaign to now, it's pretty clear that his No. 1 value is protecting himself."

The mayor has defended withholding public records from disclosure since his early months in office. In October 2012, the city's Memorial Auditorium hosted a rave that sent 16 underage partygoers to a detox unit and an emergency room. After media requests, Weinberger's team released nearly 300 pages of records but withheld passages that contained deliberative communications between city departments.

"We work really hard ... to meet the spirit and the letter of the law," Weinberger told the Burlington Free Press. "When we do hold back documents, it's almost always around protected issues around privacy rights of employees, and around protecting some space for a policy debate to happen within the administration."

He takes the same tack today in explaining why city attorneys redacted so many internal communications in Seven Days' request about the police scandal.

"You are asserting that it's the public's right to know how I come to a decision," Weinberger said. "That is not what the law says, and it's not what the court said when interpreting the law, and I think for good reason."

Indeed, a Vermont Superior Court judge sided with the city in a 2017 public records lawsuit brought by Seven Days. That fall, the Burlington City Council was poised to pick a buyer for Burlington Telecom, a closely watched debate. Days before the vote, Councilor Karen Paul (D-Ward 6) announced she'd recuse herself due to a conflict of interest. The city later refused to turn over an email that Paul had sent to Weinberger shortly before, citing the deliberative-discussion provision. Seven Days sued, but a judge ruled that the city was justified in withholding the message.

The public still does not know what caused Paul's conflict. The councilor, who ran unopposed and won reelection Tuesday, did not respond to a request for an interview.

The city also recently lost a high-profile public records case that has wide-ranging open-government implications for Vermont. In June 2017, Burlington resident Reed Doyle asked to view police body camera footage after witnessing a Queen City cop shove a teenager in Roosevelt Park. Burlington police denied Doyle's request before agreeing to let him see an edited version. Del Pozo told Doyle that he'd have to pay up to $370 to cover the staff time required to blur out the minors' faces, to protect their privacy.

"I was getting stonewalled. I was getting pushback ... and legalese thrown in front of me," Doyle said. "I called bullshit: 'Hey guys, this is ridiculous. I read the [law]. I can inspect records for free.'"

Doyle contacted the ACLU of Vermont, which sued on his behalf. He lost in Superior Court but won on appeal before the Vermont Supreme Court. The September 2019 ruling set precedent that it's free to merely inspect records, whether it takes staff time to redact information or not. Fees can still be charged for copies.

Soon after, Vermont Attorney General T.J. Donovan put his own twist on the ruling. He agreed that inspecting records should be free but argued that someone taking pictures of them should have to pay. His logic? That a photograph is a copy of the record, for which the law allows agencies to charge a fee.

Gov. Phil Scott and Secretary of State Jim Condos publicly disagreed, touching off a debate still under way in Montpelier. Legislators have discussed clarifying the law.

Burlington officials say they don't charge people who want to photograph public documents in light of the ruling. And Weinberger thinks the city's records protocols are just one way his administration has fostered transparency. He listed his open-door policy for both the press and the public; the hundreds of open, weekly chats with residents he's had over coffee and bagels; and his regular attendance at Neighborhood Planning Assembly meetings.

Weinberger beamed when describing his executive order in January that will create Burlington's first-ever open data policy. Residents will be able to follow progress on the city's climate action plan or track police use-of-force incidents. The upgrades were made "in the spirit of open government," a press release declared.

"Transparency is also about making the performance of city government more known and accessible to the public," Weinberger said. "You compare that to what was known about how city government was doing its work eight years ago, and it's a vastly different world."

'Can,' Not 'Shall'

Vermonters have had the right to access government records for more than 100 years.

In 1904, political hopeful and future governor Percival Clement asked state auditor Horace Graham for financial records to prove his assertion that spending was out of control. Graham refused, so Clement took the issue to the Vermont Supreme Court — and won.

The court's decision, handed down in 1906, set a precedent that government records are public and can be reviewed and copied. Vermont formally adopted its Public Records Act in 1975, as did many states after the Watergate scandal.

Today, the law demands that government entities turn over documents within three business days of a request. An extra seven days to respond is allowed for "unusual circumstances," such as when a request turns up a multitude of records or requires the retrieval of some that are held in storage.

The City of Burlington took more than 40 business days to respond to Seven Days' request, well beyond the legal limit.

Why? According to City Attorney Eileen Blackwood, who oversees five assistant attorneys, 36 records requests of all stripes flooded her office in the days following the del Pozo revelations.

"If we have to go through tens of thousands of documents, just, literally, we're not going to be able to do that within the time that's set in the law," said Blackwood, whom the mayor appointed in 2012.

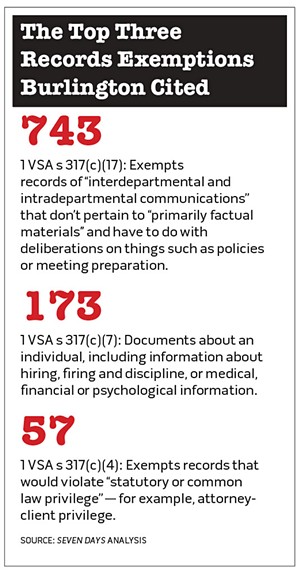

While the state Public Records Act guarantees a "free and open examination of records," Vermont law also allows for some 200 exemptions to disclosure. The city relies heavily on the one that protects deliberative discussions from disclosure. Within the documents Seven Days received, the city cited that provision 743 times out of 984 total redactions.

"We look at it and say ... 'Does this fit within the privilege?'" Blackwood said, adding that if the record does, "then generally, we are going to err on the side of protecting it."

That approach can lead to some surprising decisions.

Last year, Seven Days filed an unrelated records request for emails involving Douglas Kilburn, a Burlington man who died three days after a city cop punched him. Vermont's chief medical examiner found Kilburn died of a number of causes but ruled his death a homicide.

City Councilor Ali Dieng (D/P-Ward 7) emailed the mayor's office in April 2019, demanding to know why Weinberger and del Pozo had attempted to intervene in the medical examiner's homicide finding. Responding to Seven Days' request, the city redacted the response from Jordan Redell, the mayor's chief of staff.

The newspaper independently obtained a complete copy of Redell's message.

Weinberger had been trying "to bring transparency" to the medical examiner's review, Redell wrote: "We believe that all levels of government should be open to explaining what they have done and why."

The city's decision to withhold that passage flummoxed Matthew Byrne, an attorney with Gravel & Shea who specializes in First Amendment law.

"The thing that you're hiding from the public is your deliberations about being more transparent? That doesn't make any sense," Byrne said.

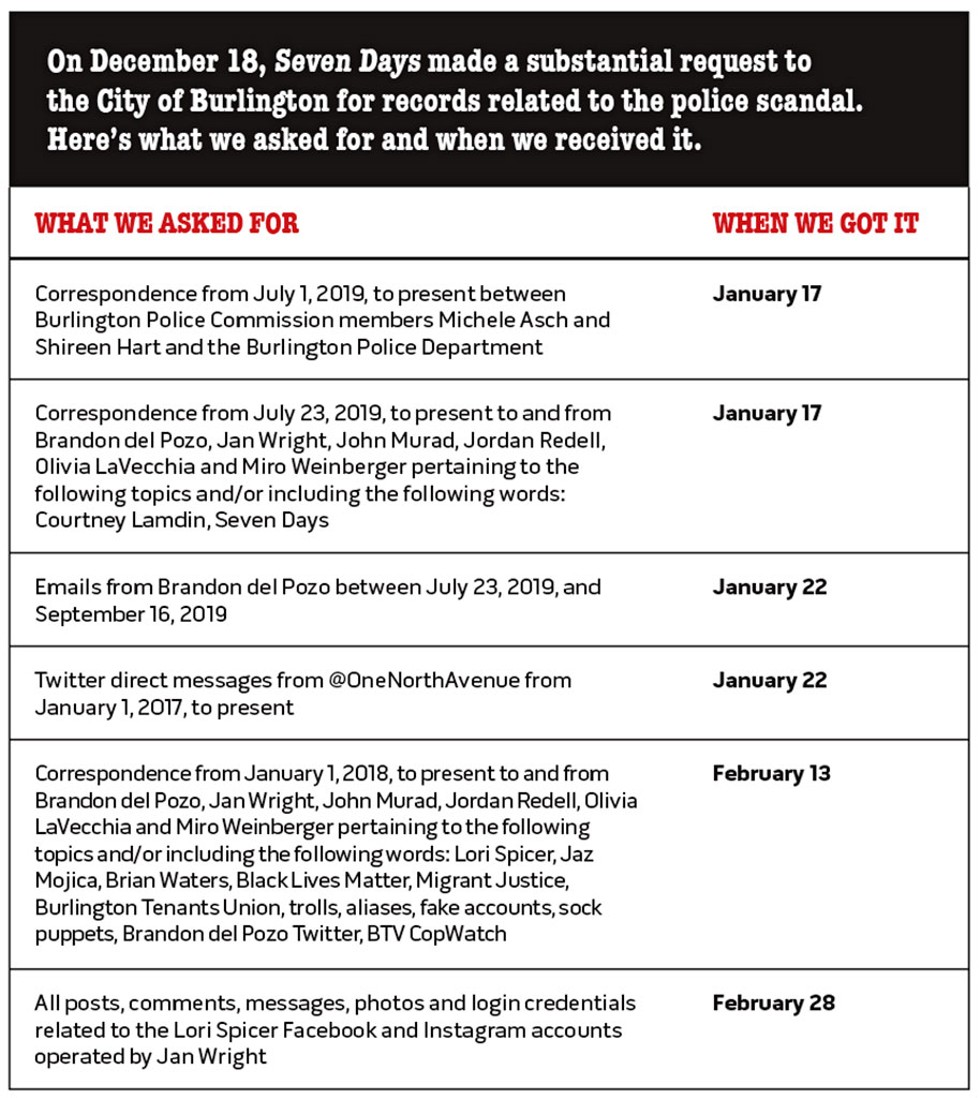

Other documents obtained by Seven Days call into question how the city interprets the law. On December 16, hours after announcing del Pozo's resignation, Weinberger faced another crisis. Wright, whom he'd just appointed acting chief, had admitted her own inappropriate social media behavior.

The records show that Weinberger sought outside advice in crafting a public statement about the latest development. He emailed a draft to Mike Kanarick, his former chief of staff who currently serves as the Burlington Electric Department spokesperson; Eric Miller, a former U.S. attorney who is now general counsel for the University of Vermont Health Network; and Neale Lunderville, who formerly served as director of the city's Community Economic Development Office.

The emails' substance was withheld. A disclaimer at the bottom was not: "Please note that this communication and any response to it will be maintained as a public record and may be subject to disclosure under Vermont's Public Records Act."

The mayor refused to release the email when Seven Days appealed, even though Miller and Lunderville are members of the public, and the exemption Weinberger cited applies to conversations between city employees. Kanarick is a city official, but the issue was unrelated to Burlington Electric business — and the email had been sent to his personal account.

click to enlarge

- Burlington redacted emails sent by private citizens weighing in on city business. Seven Days obscured Miller's phone number

Miller "is someone that I am consulting with, getting advice from in order to get these decisions right," Weinberger said. "We consider that squarely in what deliberative privilege protects."

Blackwood backed up her boss, saying city officials should be able to float ideas before acting. "We don't want to inadvertently release something that ... may be problematic," she said.

Peter Teachout, a Vermont Law School constitutional law professor, said municipalities too often use that exemption to block simple requests for information. Redacting is a knee-jerk reaction, Teachout said, comparing Burlington's technique to a doctor performing surgery with a bludgeon rather than a scalpel.

"There is a duty to engage in that kind of more refined judgment," he said.

Secretary of State Condos, who is Vermont's public records custodian, agreed. He's traveled statewide on a Transparency Tour that includes trainings and discussions on open records and meetings. One of his main messages: Just because you can redact doesn't mean you shall. Lawyers tend to censor everything, even meeting minutes that turn up in a request, Condos said, adding: "I don't understand that."

He was unaware that Burlington attorneys had done just that, several times over, in the Seven Days document dump.

Burlington resident Brian Waters was similarly vexed by the city's public records practices. He's a member of BTV CopWatch, a group that promotes police accountability by filming officers' interactions with the public.

At a city council public safety committee meeting he attended last year, police commissioners distributed a report that studied the body's oversight role. Waters got a hard copy at the meeting but recycled it, thinking the document would be uploaded to the city website.

When it wasn't, Waters filed a public records request with the city attorney's office, which denied his request. Waters appealed to del Pozo, who refused to turn it over. Both times, the city cited the deliberative exemption.

"I had a vague sense that that was wrong, but I didn't know about the public [records] law," said Waters. He has since read up on the topic and believes that documents discussed and distributed at public meetings should be, well, public.

"I'm not a lawyer," he said, "but [the law] seems pretty clear."

Ritchie Berger is a lawyer, one who has also battled Burlington over records. He's part of a group fighting a proposed second rail line near Union Station on Burlington's waterfront. Last July, he filed a request for documents related to Vermont Rail System's proposal. The city's response also widely cited the deliberative exemption in its numerous redactions, Berger said.

"It is a major impediment to transparency," he said. "Its scope is ambiguous, and it's clearly in the eye of the beholder when it comes to asserting it."

See You in Court

Once public officials have denied a records request and rejected an appeal, the only recourse is a lawsuit — a potentially lengthy, expensive proposition.

Byrne, the First Amendment attorney, filed a lawsuit in March 2010 on behalf of the Rutland Herald, which had sought records about police officers who were disciplined for watching pornography on city-owned computers. The City of Rutland had refused to release the documents, citing exemptions that protect employee privacy and records relating to criminal investigations.

Three years and nearly $100,000 in legal fees later, the Herald got the records. It took another six months for the paper to recoup roughly half of its legal expenses through an out-of-court settlement.

"When the city is determined to resist your efforts, it takes hundreds of hours to get to the final answer," Byrne said. "That's a huge burden on any individual."

The legal route is out of reach for most Vermonters. That concerns Condos, whose office fields hundreds of public records questions every year.

"It's almost gotten to the point where you either need to have a law degree or a pile of money behind you to get access to public records," Condos said. "That's not right."

Winkleman, the central character in the police scandal, couldn't afford the $862 the city quoted him for copies of records. Nor could he pay for an attorney. So for the last two months, he's rushed to city hall after work to view the documents on a public terminal computer, knowing he can inspect them for free — thanks to the Supreme Court's decision in the Roosevelt Park public records matter. On days when he can't make it, Burlington attorney Jared Carter — who represented Seven Days in the paper's quest for Councilor Paul's BT email — goes as his proxy.

"The fact that their response is, 'We're gonna do the minimum work possible and make you do the maximum work possible to get basic, basic information' shows how little they respect citizens' time and how little they respect any sort of oversight," Winkleman said.

Carter said the process discourages people from pursuing records they have a right to see.

"Nine hundred dollars for Mr. Winkleman to figure out what happened to him?" he said. "That's not transparency. That's not just."

"They'll look for every way to avoid transparency," Carter added. "This is case in point."

City Attorney Blackwood wholly disagrees but acknowledged that her staff members sometimes make mistakes. "The appeal process is there to remedy that," she said.

But Diaz, the ACLU attorney, said that's a cop-out. Burlington should be judicious with redactions from the beginning instead of reconsidering them on appeal, he said.

The city could have changed the trajectory of the social media scandal "if everything had been brought out in the open in the first place," Diaz said.

During a February 19 interview, Blackwood wouldn't say whether she agrees with that sentiment. Nor would she comment when asked whether the city had released all relevant information about the scandal. But she did say that the city takes the threat of public records lawsuits seriously.

And then she laughed.

"The irony is that we got served with a suit yesterday," Blackwood said. "I got served by the sheriff."

Seven Days obtained the suit, which is unrelated to the police scandal. South Burlington resident Laura Waters had requested records in January related to Burton Snowboards' planned redevelopment on its Queen City Park Road campus, which would include a new entertainment venue. One document, a proposal for an engineering study, was completely blacked out. Another, a traffic study, was pockmarked with more than 130 redactions. City lawyers overwhelmingly cited interdepartmental deliberative privilege, despite the fact that some communications were with consultants — not city employees.

"It was just mind-boggling," said Waters. "They gave us completely black pages, like it was some CIA undercover secret."

She sued to obtain the traffic study on behalf of neighbors concerned about the project. Within days of Waters' filed suit, and following Seven Days' interview with Blackwood, the city reversed course and turned over the study in full. Waters suspects that the city abuses its power to shield public information because officials assume people won't pursue it.

"We're in this for the long haul," she said. "If something like this comes up again, we'd be more than happy to see them in court."

Andrea Suozzo contributed data reporting.

Correction, March 6, 2020: A previous version of this story misidentified the meeting Brian Waters attended last year. It was a public safety committee meeting.The original print version of this article was headlined "Redacted | How the City of Burlington keeps the public in the dark"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Courtney Lamdin

Bio:

Courtney Lamdin is a news reporter at Seven Days; she covers Burlington. She was previously executive editor of the Milton Independent, Colchester Sun and Essex Reporter.

Courtney Lamdin is a news reporter at Seven Days; she covers Burlington. She was previously executive editor of the Milton Independent, Colchester Sun and Essex Reporter.

More By This Author

Latest in City

Speaking of...

-

The Café HOT. in Burlington Adds Late-Night Menu

Apr 23, 2024 -

Burlington Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s First Term Starts With Major Staffing and Spending Decisions

Apr 17, 2024 -

Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont

Apr 10, 2024 -

Middlebury’s Haymaker Bun to Open Second Location in Burlington’s Soda Plant

Apr 9, 2024 -

Police Search for Man Who Set Fire at Sen. Bernie Sanders' Burlington Office

Apr 5, 2024 - More »

find, follow, fan us: