Published November 11, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated November 11, 2015 at 1:32 p.m.

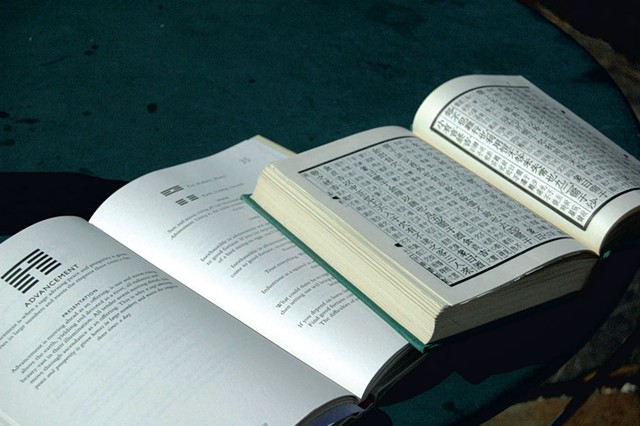

"Ask anything you want, and we'll see what happens," says David Hinton on his sunny porch in East Calais. He rolls three quarters and writes down their corresponding values: three for heads, two for tails. The much-lauded translator, essayist and poet recently translated I Ching: The Book of Change, the classical Chinese book of wisdom, and has agreed to do an I Ching reading for this reporter.

"[The I Ching] is very philosophical, so the more probing your question is, the more relevant the answers will be," Hinton says. I choose a weak but safe question — "Should I finish my articles in the next couple days — hoping that ancient Chinese wisdom will confirm that I should play outside in this unusually warm autumn instead of work.

The original I Ching consisted only of 64 hexagrams, or figures composed of six horizontal lines. Their corresponding names and interpretations were added over the centuries, with the canonical I Ching completed around the third century BC. Other English translations of the classic text include extensive commentaries and historical context; Hinton's version is notable for its eloquent sparseness, and for its ability to retain, instead of explain, the mystery of the text.

Hinton has the background for the job, having extensively translated classical Chinese poetry and philosophy, including Tao Te Ching. Also the author of a meditative memoir called Hunger Mountain: A Field Guide to Mind and Landscape (2012), he has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and multiple fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts.

After rolling the three coins, Hinton tallies up the values for each roll and consults his book to find and draw the corresponding lines, which represent feminine yin (a line with a gap in the middle) and masculine yang (a solid line). Once he's done this six times, we have the hexagram, which leads us to I Ching 35: Advancement. Hinton begins the interview by reading from his translated commentary.

"Advancement is when a sage advising peace and prosperity is given horses in large numbers and meets the emperor three times a day.' Boy, I don't know how to apply that to your question. Do you?"

SEVEN DAYS: Well, I don't think it's advocating procrastination.

DAVID HINTON: No, it's advancing, so the first thing is, yeah, do it. In [ancient] Chinese governing, emperors had lots of advisers, and the advisers were supposed to tell the emperors how to act. Often, if they told the truth and were critical, they'd get in trouble. So this is saying that advisers who advise peace and prosperity, if they tell the truth, are rewarded — that's how things should be.

[Reading on]: "Trust everything. What could there be to regret?" I mean, if you live deeply enough, which is impossible to do, life, everything, is so wondrous that, what do you have to gain or lose? Almost nothing; it's so small compared to the sheer wondrousness of everything, of being alive, that it doesn't matter that much. That's a pretty difficult place to get to.

SD: What were the original meaning and interpretation of the I Ching?

DH: The I Ching is complicated because it was so early in the language. It was the first real book. It's not clear what its original meanings were, and even meanings of words sort of evolved over time. It's this sort of urtext, the place where words get their meaning, but since it's the first one, people weren't sure what that meaning was. It came to be read, over the centuries, according to how people were thinking at the time.

They say that the very, very earliest meaning of this had to do with sacrifices and things like that, and that it evolved into this wisdom text. Even in Lao Tzu's time, in 600 BCE, people would have been reading this in a Taoist way, like I'm describing to you.

SD: You write in the introduction about early efforts to use I Ching for practical purposes. How can contemporary readers view or utilize the text?

DH: [The I Ching] has a deep ecological worldview. In the West, humans are seen as separate from the rest of existence — [that view] says we're made from spirits, from different stuff than the earth.

I Ching is always kind of universal, lets you think about your life and how to move forward. Divination assumes that there's someone controlling your fate and that you can have access to that [through prayer and such], but I Ching assumes that you're part of the process of change; all it's doing is telling you where you are in that changing, and how to think about the whole situation.

It's a very different idea of the cosmos; it's this constant unfolding. The West says that God created everything and controls it — that's the kind of male thing — and this is a more female thing, that everything is growing from the inside. So you're just saying, How are things growing, and how should I think about it?

I think the ancient Chinese thought of this more as philosophy, rather than fortune telling. This book sort of helps you [find this] other way of experiencing reality, as you being part of this flow of change, in your everyday life. It helps you think about how to cultivate wisdom in this other way to live, of seeing the world, which is the same reality, just seeing it differently, as this generative process of change.

[One could read this] in general as a wisdom text, the same way you could read Tao Te Ching, which is the most translated book in the world — because you want to understand life a little deeper. I hope the introduction orients you, and then you just have to keep reading, like any good book, and then maybe it leads you to Tao Te Ching. If you sit and read the two of them, you should really get this other way of thinking about things.

But other than that, I mean, what good is that? Maybe it's no good at all. What good is philosophy, what good is thinking about your life? [Laughs.] I don't know. I still don't know.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Translator David Hinton Retains the Mystery of I Ching"

More By This Author

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.