Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

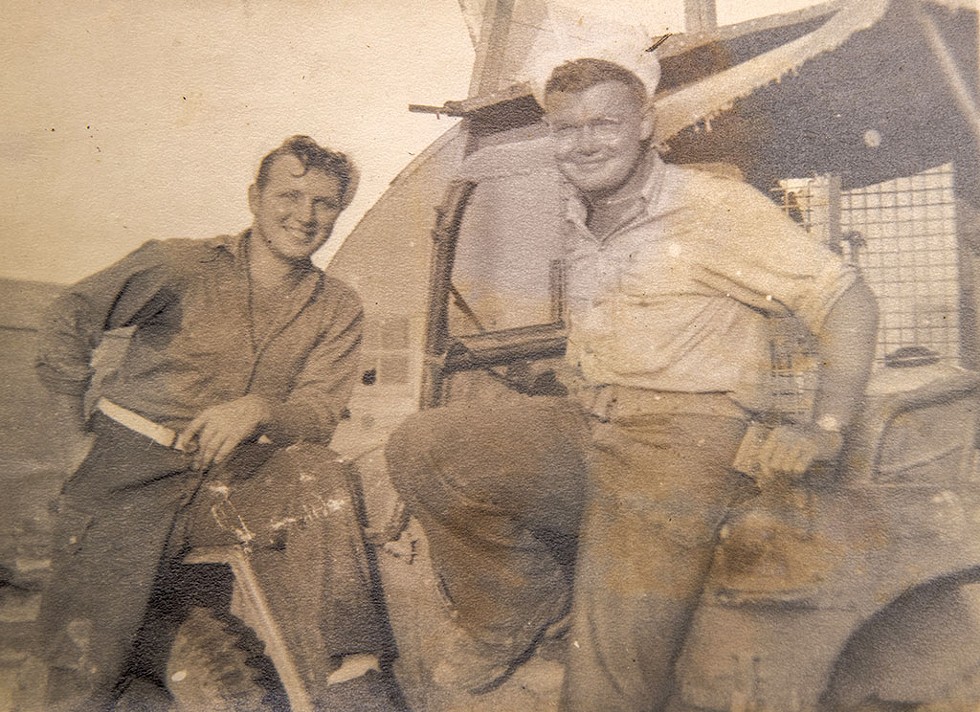

Alive to Tell the Tale: Vermont's Remaining World War II Survivors Bear Witness

Published May 26, 2021 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated June 22, 2021 at 5:02 p.m.

Memorial Day was conceived to honor the fallen. During World War II, 1,233 Vermonters gave their lives in service to their country. Can we understand their sacrifice without turning to living witnesses, a dwindling cohort that retains primal memories?

Some 16.1 million Americans served in the armed forces as war raged nearly 80 years ago; 406,000 died. Despite Vermont's modest population, its participation was outsized. More than 50,000 Vermonters enlisted or were drafted into military service. Almost every family had somebody in the armed forces, and many had several.

Lifting the curtain to see behind these stark numbers reveals memorable acts of valor. Left behind in the Philippines when the Japanese invaded, Pittsfield-born Earl Cook of the U.S. Army Air Forces waged guerrilla warfare against the enemy for a year until the United States regained control. Army Capt. Kimball Richmond of Windsor received the Distinguished Service Cross for taking charge of an ad hoc unit at Omaha Beach on D-Day after his own landing craft was sunk, forcing him to swim to shore. Maj. Gen. Leonard "Red" Wing of Rutland served in both world wars and became one of only three National Guard officers to command a combat division.

Not everyone saw combat. Fewer than half of American service personnel were involved in fighting, according to the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. Soldiers trained and ready were not deployed; others were destined for the Pacific theater when the atomic bomb was dropped and abruptly ended the war.

Fewer than 200,000 American veterans of World War II survive: They were dying at a rate of nearly 300 a day before the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. In Vermont, the number of surviving vets dropped to below 800 last year.

They've become known as the Greatest Generation, a grand superlative for sure — but what does it mean? How do you memorialize 18-year-olds wrenched from their Vermont farms and thrown into the maw of battle — boys too young to have a beer but old enough to wield deadly force? They won the war, but at home — for many — their own peace was elusive, even as they went back to school or entered the civilian workforce.

Every soldier has a story, and Seven Days sought them out. Here you will meet the oldest living veteran in Vermont, who is also one of the oldest in the nation; a fighter pilot returning from a night mission seeking safety on an aircraft carrier deck in an immense, roiling sea; an infantryman at the Battle of the Bulge, where the arctic temperatures were as deadly as the enemy gunners; and a Navy man in Tokyo Bay with a front row seat for the ceremony marking the Japanese surrender.

These are our fathers, grandfathers, great-grandfathers — ordinary folks thrust into an extraordinary situation. They are heroes, though none would claim that word. They are living chronicles of a cataclysm.

My feet got such bad frostbite it still bothers me.

James Donald Carr

The Battle of the Bulge

If the screaming meemies didn't get you, there was always the cold. The meemies were the German mortar shells, Nebelwerfer, that exploded in the frigid air over the Hürtgen Forest in the winter of 1944-45. Hear a meemie, stand next to a tree, veterans told replacement troops; hug it if you have to.

But the cold — the deep, unrelenting cold — was a more constant enemy, young Private First Class Jim Carr of Bellows Falls learned during his first hours in the forest on the Belgian-German border. It was so damn cold. Sleeping bags froze to the ground. The small bottles of beer his sergeant distributed after one patrol were frozen solid.

It seemed only yesterday that Carr had turned 18 and his draft notice had arrived. It was early 1944, and the Normandy invasion was imminent, so the Army pushed him quickly through basic training, assigned him to the 112th Infantry and shipped him to France. There, his platoon leader handed him a 24-pound weapon, anointing him the unit's Browning Automatic rifleman. The M1918 BAR was a light machine gun capable of firing 650 rounds per minute.

"The BAR man had been killed the day before," said Carr.

He was still two months shy of his 19th birthday when he marched into the Hürtgen Forest, five miles east of the German-Belgian border.

He remembers vividly the day Sgt. Francis Liburdi rounded up a patrol to count the German troops massed nearby to record their movements. Carr and the others were crouched in some bushes near the tree line, where the snow was thinnest. But the recon was cut short; a new second lieutenant came along, tripped a mine and fell, injured. "Let's get the hell out of here!" Liburdi yelled.

"We started to run ... [but] the Germans had the trail marked out and started to drop mortar shells on us," Carr recalled.

The Battle of Hürtgen Forest was bad; what followed seamlessly was worse. This was the Battle of the Bulge, a last desperate lunge by Adolf Hitler's forces to stave off defeat. For six weeks, beginning in mid-December 1944, 30 German divisions with nearly 250,000 men pushed into the Allied line in the hilly Ardennes Forest on the border between Belgium and Luxembourg. The American wall bent but did not break — thus the "bulge" — but the human cost was fearful: 100,000 U.S. casualties. As many as 15,000 suffered severe frostbite and other injuries from snowy terrain and temperatures that plunged as low as 30 below.

The 112th was ordered to a position in Belgium.

"We did not have good winter gear, such as warm footwear, spare socks or underwear," Carr recalled this month at the home in Bellows Falls where, at 95, he still lives independently with Gloria, his wife of 70 years. "My feet got such bad frostbite it still bothers me."

"They finally gave us sleeping bags — I still have mine. Boliver Hyland, an older veteran, showed me how to fix the bag so it was very warm. I sewed a blanket onto the liner. This bag did not leave my person," he said.

"Most of the time— and I'm not ashamed to admit it — I was scared," he said. "A lot of times we were exceptionally lucky. A couple of my friends were 18 years old; we had some elderly guys that took care of us. They showed us how to be men, you know."

There were other battles for the 112th, but none rivaled the Bulge. When the war ended, Carr was set to be discharged but had a painful boil on his left wrist. "I was worried they might keep me," he said. "So I got some hot water in my helmet and soaked it until I got it down."

It took Carr some time to locate his family upon returning to Bellows Falls; his mother's house had been destroyed by a fire on Christmas Day 1945. "The State of Vermont gave us $20 a week for a year, and I took the money and a year off," he said. "I finally had to go back to work at St. Johnsbury Trucking, as I had run out of money." Later, he worked as a dispatcher for Holmes Transportation and then as plant manager at Rockingham Memorial Hospital.

At home, like so many other veterans, Carr avoided talking about the war. His family respected his boundaries and never pressed him for stories.

"I think what he saw was just too disturbing — and he was really young," said his daughter, Jeanine Carr. "You know, he saw a lot, and he experienced a lot of physical discomfort from the severe frostbite. And the emotional pain made it just hard for him to talk about."

It's not going to happen to me — it's going to hurt the other guy. I totally embraced that mentality.

Richard Austin

Navy Bomber Pilot

Night bombing runs off aircraft carriers were still new — they'd only begun in January 1944 — and U.S. Navy pilot Richard "Dick" Austin would never get used to them.

His Avenger torpedo bomber was designed for floating airfields like the USS Yorktown, but any night run was a crapshoot. Daylight allowed him to visually check his altitude, speed and direction, providing precious time for adjustments. But it was night for this particular landing, and from the cockpit, Austin was looking at a dark mass undulating in a black sea under a starless night sky.

"Depth perception is useless above the water, so you're worried that you may be too low," he recalled 77 years later, in the comfort of his room at the Wake Robin retirement community in Shelburne. "You need to be lined up straight with the carrier, 15 feet above the deck. Too far right, and you obliterate the island where the bridge and air control are stacked; too far left, and you flip into the churning sea ... So you try to adjust on approach ... but there's no time."

Austin was terrified. He landed safely that evening and dozens of other times. It was never routine.

"I was very frightened by the demands of adjusting in the last seconds before I saw the deck. The landing signal officer with his lighted paddles helped — but not nearly enough to kill your anxiety," Austin said. "And, really, you don't have time to indulge that anxiety, because if you don't make adjustments, your life is threatened."

To think, Austin had never flown a plane — never even built a model airplane — until a few years before. He was attending St. Lawrence College in New York State when a civilian pilot training program was introduced for credit. It was love at first flight; Austin was the first in his class to solo, first to get a pilot's license. In the spring of 1942, he was working on Wall Street when the Navy called. Austin quickly progressed through advanced flight to torpedo training.

And now he was flying off the Yorktown. Pilots practiced on airstrips with markings approximating a carrier's safe landing zone, but they couldn't simulate the real thing. Fear forced a mindset of displacement.

"It's not going to happen to me — it's going to hurt the other guy. I totally embraced that mentality," Austin said of the self-delusion that got him through the war. "How an infantryman could climb out of a trench and attack a machine gun nest — [it] would only be possible if he had that attitude."

For Austin, the "other guy" was his friend Frank Frazier, who was shot down off the coast of Formosa, now called Taiwan, captured by the Japanese and imprisoned late in the war. "He was beheaded the day before the armistice was signed," Austin said. "What a waste."

Austin nearly ran out of gas on a run over Formosa in 1945, but nothing equaled a close call he had in the Philippines the year before. The fact that the risk resulted in a fool's errand is something Austin laughs about now.

"One bad-weather day we were attacking shipping in Manila harbor, and we had been told there was a Japanese carrier in there a couple of days before. Six of us attacked this long, low profile in the harbor, thinking it was a carrier. Five of the six torpedoes hit this thing, and it sank ... As I was approaching that drop, there was a Japanese anti-aircraft battery on the coast ... tracking me, and you see the anti-aircraft fire coming up behind you. Our training said in that situation you want to change direction, speed and altitude, and it will throw off their accuracy. I was changing my speed, but I was pretty scared that time. You knew those bastards were trying to kill you!"

Austin, who turned 99 in March, leaned back in his chair. After film of the bombing was developed, he confided, the target turned out to be an American floating dry dock that the Japanese had captured years before.

"So we all claimed that we were the one torpedo that missed — who wanted to tell our girlfriends that we sank the USS Dewey?"

Austin married his girlfriend, went to medical school and practiced as a surgeon for three decades in the Boston area while he and his wife, Marcia, raised two girls. An avid skier, he made many trips to Vermont and moved to the Green Mountains in 1994.

The love of flying that steered Austin's military career persisted into his years as a surgeon and into retirement. Marcia, who has since died, almost put an end to that hobby. When Austin was living in Boston, he used to go to a small airfield and rent a plane for solo flights. "I came home and told my wife, 'I had a nice time flying today.' And she said, 'Goddammit, if you can waste $75, so can I,' and she'd go out and buy a new dress. So it was costing me $150 each time to keep it up!"

Thank goodness I didn't have to take another person's life.

Herbert Johnson

Seabee Stalwart

Herb Johnson was working the skidder, pulling big mahogany logs to the sawmill so they'd have planks for the barracks. Everything was mahogany, even the outhouses. The ground in Milne Bay, New Guinea, was sodden from torrential rains, so it was taking twice as long as it should have. The sergeant — Earl, his name was, from the South — switched Johnson to guard duty one day.

"You know what you're going to do, son?" Earl asked.

"Yeah," Johnson replied. "I'm going to watch the trees, and if I see a puff of smoke, I'm going to shoot at it."

"Son," Earl drawled. "If you see a puff of smoke, you're dead! Or dying."

Thinking back from the distance of nearly eight decades, Johnson realized he was naïve about the danger. "I was still a teenager, and everyone really didn't have a sense of what could happen," he said. "I don't remember feeling scared then — but there was time for that ahead."

Johnson, who will be 96 on June 3, vividly recalled arriving in New Guinea in May 1944. The jungle seemed impossibly exotic. Two years earlier, Milne Bay had been the site of the Allies' first ground victory over Japanese forces, and the sheltered bay on the eastern tip of the island still had strategic as well as symbolic importance.

Johnson was a Seabee — a member of the Navy's construction battalions, or CBs — the construction arm tasked with building roads, runways and almost anything aboveground. Johnson had worked construction in high school; it was something familiar in a disorienting experience. His trip through the Panama Canal with Naval Construction Battalion 118 was his first time on a ship.

It was almost a relief when his battalion got orders in March 1945 to leave the stink, heat and tropical downpours of Milne Bay and sail to the island of Mindanao in the Philippines. Johnson was among 100 Seabees deployed to the City of Zamboanga to construct a base headquarters. Not long after arriving, they learned that they were to be among the first to deploy in the widely anticipated invasion of mainland Japan.

"We just knew we'd be cannon fodder," Johnson said. Months passed, leaving everyone edgy. On August 6 and 9, atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On the 10th, NCB 118 was ordered to move to Subic Bay, which improved their position for an invasion.

The battalion remained there until the Japanese surrendered. "I used to go out at night with some of the older guys, who taught me how to run the heavy equipment," Johnson said. In a short while, Johnson mastered the bulldozer and what he called a "scraper."

Once peace arrived, he found work at home relatively easily running heavy equipment. While digging out a swimming pool, Johnson attracted an admirer — the homeowner's daughter. "I asked if she wanted a ride, and she climbed up on the toolbox," Johnson recalled. "And that was it."

The Caterpillar courtship culminated in the marriage of Herb Johnson and Betty Bedrosian. They lived in Somers, N.Y., and Florida before retiring to Pillsbury Manor, now Allen Harbor, in South Burlington in 2014. Betty passed away three years ago.

Johnson is a quiet man. He hesitated before reflecting on his wartime service.

"I personally learned a trade — I guess that's kind of greedy," he said. "On the other hand, I was trained and carried a weapon, and I was prepared to use it.

"Thank goodness," he added, "I didn't have to take another person's life."

When I say my prayers at night, I ask the Lord, "Please give me another day."

Leonard A. Roberge

Serving Stateside

The back room of the Boston Post Office was packed with guys like Lenny Roberge: Navy enlistees waiting to learn their fate. But when a yeoman emerged from an office shouting, "Can anyone here type?" only one hand shot up —Roberge's — which he later confessed had not come into contact with a typewriter key for quite a while.

It was October 1942, and the native Rutlander soon found himself logging mail in the captain's office at the Casco Bay station in Portland, Maine. Yeoman 3rd Class Roberge quickly extended his activities to taking over the station's newspaper deliveries, which earned him extra cash to court his girl back home.

On June 12, Roberge will celebrate his 107th birthday, surrounded by family and friends and some fellow veterans of World War II. Roberge is Vermont's oldest surviving veteran and likely one of the oldest dozen American vets. Old enough to have lived through two worldwide pandemics a century apart. Wise enough to have no regrets that his service in the war kept him stateside.

He married his girlfriend Agnes in 1943, and then spent 18 hours on weekends riding trains to and from Rutland so that he could spend eight hours with his new bride. Lenny's unit was transferred to a naval station in Connecticut for additional training in 1944, and three months later he was ordered to report to a base in San Francisco — the last stop before deployment to the war in the Pacific.

"I realized how different this assignment could be, how my life could change," he recalled. "But the atom bomb changed everything."

Roberge reflected for a moment when asked whether he understood why that horrific act is controversial today. He uses a walker to get around the Allenwood nursing facility in South Burlington, where he now lives, but everything else about him belies his age: his memory, his wit, his daily calisthenics.

"No one knows if they hadn't dropped the bomb how many more people would have died," he said. Nor did he feel cheated by avoiding combat. "Agnes knew she no longer had to worry about my safety day and night."

Because he was married, Lenny was in the first wave of enlisted men eligible for discharge. The Navy transferred him to South Station in Boston, and he and Agnes took a room in Cambridge until his tour ended in December 1945. The couple settled in Brattleboro, where Lenny began working for Central Vermont Public Service, a utility company; he later sold home appliances. In 1950, he bought an 80-year-old house in Brattleboro and soon developed a sideline in home renovations. Lenny and Agnes raised three children in Brattleboro before moving in 1991 to Allenwood, where Agnes died in 2017.

Lenny was born in 1914, the year the first stone was laid for the Lincoln Memorial and a promising player named George Herman Ruth made his major league debut. Yet for a visitor in early spring 2021, he cracked jokes, sang two songs and displayed a prodigious memory for events of 80 years ago.

Lenny's own prescription for longevity seemed quite simple: "We only have one birthday a year — and that's a good thing!" he said.

Among Allenwood staff, he inspires awe and affection in equal measure.

Lenny gripped his walker and shuffled out the door, only to return a few minutes later with a slice of apple pie for his visitor. "You have to stay busy," he declared. "When I say my prayers at night, I ask the Lord, 'Please give me another day.'"

It felt like you're holding your breath.

Alvaro Richard Boera

Postwar Peril

Dick Boera faced his greatest danger once World War II was over.

Hostilities had ceased, but Navy Lt. Boera — "single and carefree," in his words — remained with the light cruiser USS Portsmouth for what was conceived as a postwar goodwill tour. As it turned out, this benevolent mission involved a treacherous run through unmapped minefields off the coasts of western South America and northwest Africa.

Even training aboard minesweepers before the 1945 voyage was little help. "That was scary," said Boera. "It felt like you're holding your breath, hoping you wouldn't accidentally run across one of these loose cannons. And there was a real danger, mainly because not only were they unmapped as far as the German mines were concerned, but it turned out that the U.S. mines had not been well mapped at all."

The Portsmouth sailed blindly through dangerous seas for five days on the monthslong 20,000-mile trip. No electronic detection devices to assist — "just good eyesight on the part of anybody up in the stacks. Even so, most of the mines were down below the waterline. It was dumb luck." As an engineering officer, Boera was stationed belowdecks, which spared him most of the minute-by-minute tension on deck.

Boera had tried to enlist before he turned 18 and was rejected, so his commission came late enough in the war that he did not see combat. He wondered about the sanity of anyone who might feel cheated by avoiding combat. "I was prepared [to fight], but fortunately for me things worked out differently ... I was a little ashamed of the fact that I hadn't seen real action, but how many of us never saw battle? And the Navy took a beating: Anytime a ship was sunk, they lost probably 90 percent of the crew."

Boera's first name, Alvaro, is courtesy of a Spanish grandfather. He grew up in New York City and enrolled at New Jersey's Princeton University in 1942. After enlisting in the Navy, Boera transferred to the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J., which offered an officers' candidate program that allowed him to stay in college. He finally put to sea early in 1945.

He stayed in the Navy Reserves until 1965. After working as a business manager at Staten Island Community College, he accepted a similar post at Lyndon State College in 1970. Boera's wife of 68 years, Julie, passed away in December while they were living at Allen Harbor in South Burlington.

Asked about his memories of the war, Boera, 95, recounted a meeting he had just before he got his Navy commission. He'd driven to Princeton to reconnect with old friends and was strolling along Mercer Street when he passed an address that struck a chord. Never shy, he knocked on the door and was greeted by a housekeeper who allowed him inside.

"I was led into a study and introduced to professor Einstein," Boera recalled. "He looked exactly like his photos: gray-white unkempt hair, a Teddy Roosevelt mustache, wrinkled sweatshirt, sad but twinkling eyes." The renowned formulator of E=mc2 invited him for tea and sat down to chat. "It was," said Boera, "like having a conversation with my beloved German grandfather."

We weren't ashamed to burst out into tears ... We [knew] that it was finished and they weren't going to get us.

Leney Barclay

Witness to Japan's Surrender

Nearly 300 ships of the Allied powers appeared as stepping-stones across Tokyo Bay, leading to the hulking, 45,000-ton battleship USS Missouri. On the veranda deck, Gen. Douglas A. MacArthur waited to receive the formal surrender of the Japanese Imperial Army, marking the end of World War II.

Just a few hundred yards away aboard the Fletcher-class destroyer USS Knapp, 21-year-old Petty Officer Leney Barclay emerged from belowdecks, where he'd been firing the boilers. He could see the Missouri off the starboard bow. Wearing dungarees, a T-shirt and a blue cap — regular kit for destroyer crewmen — Barclay headed toward the bridge, where his pal Charley Thompson was watching the smokestacks for any sign of engine malfunction. Virtually all of the crew were on the main deck, staring across the sea at history. It was shortly after 8 a.m.

The bridge afforded the best view, Barclay knew, and besides, Thompson had a pair of powerful binoculars that could spot enemy aircraft from 10 miles away. "We kept exchanging them with each other as we watched the Japanese come," Barclay recalled by phone from the Vermont Veterans' Home in Bennington.

More than three-quarters of a century had passed, yet Barclay could picture it all, even the officer who came up to the bridge to record the date as September 3, 1945. That put the ship's log at odds with Western history books, which cite the surrender date as September 2 — because in Europe and America, it still was September 2.

Though he's 97 now, Barclay tells the story as though it happened yesterday:

"The first thing we noticed was a small boat pulled up against the side of the Missouri. They had a big long stairway going up from the water up to the first deck. This Japanese delegation had a couple of guys with canes, and they were struggling ... to climb up this stairway, and it took quite a while." (The delegation leader, Japanese foreign minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, had an artificial leg.)

"And all were dressed in what we might consider tuxedos, but very strange old-fashioned tuxedos with top hats! They all got to the top there, and it seems that the whole crew of the Missouri was piled around that part of the deck. Because we were aligned with the tide facing in the same direction, I could see the ships were just jam-packed with sailors. We passed the binoculars back and forth and described what we were seeing. They made all their speeches, and then they got to the point.

"...When MacArthur signed [the surrender document] ... he passed a pen to a little skinny guy. It was Gen. [Jonathan M.] Wainwright, who was with him in the Philippines and had spent three years in the prison camp in Manchuria. I said, 'Oh, my goodness, that was a great gesture.' That was a great thing. He could have easily put the pen in his pocket ... It was a beautiful picture, like a Broadway show going on right here on the deck.

"Thompson and I, you know, we had tears in our eyes. We [said], 'My God, Tommy, it's over with. We've made it. We've made it!' I'm telling you, we weren't ashamed to burst out into tears. A lot of us guys were crying. Because we [knew] that it was finished and they weren't going to get us."

Barclay paused, and then added, "We knew we were getting ready to invade in November. And we knew that it was gonna be a slaughterhouse ... They had hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of suicide planes ready to attack guys. And we were, we were so very, very fortunate that we had escaped."

Five months later, Barclay returned to his native New Jersey and, thanks to his experience as a water tender, got a job as a plumber. Eventually he married the boss' daughter, Mary, and took over the business. In 1954, they moved to Vermont and spent the next 17 years in Londonderry, raising four children. The entire Barclay clan joined the Peace Corps in 1971 and spent years in Southeast Asia and Africa. Mary died in 2009.

"We have a destroyer crew reunion set up every two or three years, and we meet someplace around the country. We had to invite some crews from the Korean War," he added quietly. "I'm the only one left from the Knapp."

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: History, Memorial Day, Wold War II, James Donald Carr, Richard Austin, Herbert Johnson, Leonard A. Roberge, Alvaro Richard Boera, Leney Barclay

About The Author

Steve Goldstein

Bio:

Steve Goldstein is a veteran newspaper reporter, mainly with the New York Daily News and the Philadelphia Inquirer. He served as Moscow and Washington D.C. bureau chief for the Inquirer. He has traveled to 73 countries and reported from most of them.

Steve Goldstein is a veteran newspaper reporter, mainly with the New York Daily News and the Philadelphia Inquirer. He served as Moscow and Washington D.C. bureau chief for the Inquirer. He has traveled to 73 countries and reported from most of them.

More By This Author

Latest in History

Speaking of...

-

Vergennes Memorial Day Parade Draws a Patriotic Crowd

May 29, 2023 -

Parades and Pups: Memorial Day With Democratic Rivals for Vermont's U.S. House Seat

Jun 1, 2022 -

Burlington Nonprofit Takes People With Cancer Sailing on Lake Champlain

May 26, 2021 -

Stay-School Adventures: Memorial Day, Quarantine Day 73

May 27, 2020 - More »

find, follow, fan us: