Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Bennington Locks Up More People Than Any Other Vermont County

Published March 9, 2016 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 2, 2018 at 9:52 p.m.

More than 300 Vermonters have died of drug overdoses in the past three years. But rarely has a dealer faced criminal charges as a result. A St. Johnsbury woman received a suspended sentence of two to five years for selling a fatal dose of heroin to a Groton man in 2014. Two years ago, a Burlington dealer allegedly sold heroin to his roommate, who took 24 hours to die on the premises. For that, he faced two years in prison.

But Trevor Shepard is looking at a much stiffer penalty — 20 years to life — for allegedly selling the heroin that killed Bennington resident Clark Salmon last month. State prosecutors have charged him with second-degree murder.

Defense attorneys across Vermont were shocked by the severity of the charge — none could recall a drug dealer here ever being convicted of murder. Stephen Saltonstall called it "over the top" and "a bad use of prosecutorial discretion." The former Vermont defense attorney noted, "You could charge virtually every drug dealer with a crime like that."

But no one was surprised about which state's attorney's office levied the charge.

"I just chalk it up to Bennington," Defender General Matt Valerio said. "That's the way it's always been down there."

The murder charge against Shepard is the latest example of aggressive prosecution in Bennington County, according to legal observers, where State's Attorney Erica Marthage and her four deputy prosecutors punish perpetrators to the full extent of the law. Critics say their approach is increasingly out of step in a state determined to reform its criminal justice system and reduce the inmate population.

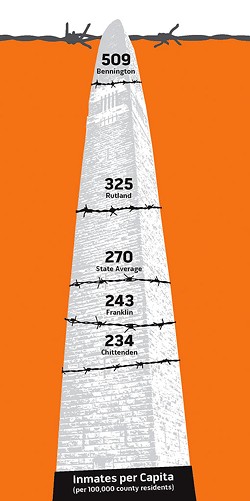

Bennington County sends almost twice as many defendants to jail as the state average and, though it has never had the highest crime rate, has beat out every other county's incarceration rates since the Department of Corrections began tracking the data in 2009. Even Rutland County, which police and politicians have portrayed as ground zero in Vermont's opiate war, generates about 64 percent fewer inmates per capita than Bennington County.

"It's a different world," said Fred Bragdon, the head attorney in the Bennington County Public Defender's Office. "I tell the prosecutors all the time: We could sit down and ... figure out one-quarter of defendants from Bennington that could be released right now."

But Bennington County doesn't operate any programs to help people to avoid incarceration, while prosecutors and judges in nearly every other Vermont county have "drug court," "mental health court" and "rapid intervention community court" — all of which are designed to get defendants into treatment instead of jail.

Bennington uses the traditional criminal justice system to seek maximum time for cases ranging from trivial to severe. In recent weeks, county prosecutors launched an investigation of an inmate who was helping other prisoners draft legal documents, in violation, they allege, of an obscure law that is almost never enforced in Vermont. More seriously, last month the Vermont Supreme Court overturned the drug conviction of a 27-year-old man whom Bennington prosecutors had put away for a decade. He had already served two years when the judges ruled, but Marthage and company made Shamel Alexander wait almost another month in jail before releasing him.

"It's wrong, what's happening here; it really is," said one longtime Bennington County defense attorney, who requested anonymity in anticipation of future dealings with Marthage. "Everything is done to the max, in terms of conditions of bail and sentencing. The drug problem in Bennington is as serious as it is in Rutland, Burlington and Windsor, but that's being used as a cover. The mantra here is punish, punish, punish."

Marthage said she is simply following through on the promise she made to voters — to keep the community safe. And the Manchester native is no stranger to southwestern Vermont. She was a deputy state's attorney in Bennington County for four years before she ran for the top prosecutorial job as a Democrat 10 years ago.

Each of Vermont's 14 state's attorneys has a different approach, she said: "We're elected to represent the needs and priorities of the counties."

But isn't there an argument to be made for uniform legal treatment across the state? Recent Bennington County cases illustrate a long-held concern about Vermont's criminal justice system: that defendants may be treated very differently, and receive wildly varied sentences, depending on where they happen to be arrested.

Case 211-02-16

Bennington, a town of 15,700, boasts a walkable downtown and a small liberal-arts college with long list of artsy alumni. But there's nothing quaint or historic about the Bennington County Superior Court, which is on the edge of town in a state office complex that was built in 2012. With faux wood paneling, a light-filled atrium and gently sloping interior walkways, the building feels more like a hospital wing than a Vermont courthouse.

On a gray Wednesday afternoon in mid-February, Bennington Superior Court Judge David Howard slowly walked to the bench inside courtroom No. 2 and came upon a languid post-lunch scene. The bailiff was chatting up a young female court staffer, lawyers talked quietly, and a local newspaper reporter shuffled in and out.

"Case 211-02-16," Howard said quietly, calling the number of the first case on the afternoon docket. Case numbers are composed of three separate numbers — the number of cases filed in the county year to date, followed by the month and calendar year.

Howard turned to a court clerk. "It can't be 211. We can't have 211 already, do we?" he asked with incredulity.

After a moment's pause, the clerk confirmed the count was accurate.

"Oh, OK, I guess I lost track of how many cases have been filed," Howard said.

Case 211-02-16 turned out to be an arraignment. A 34-year-old woman with a string of minor, nonviolent convictions on her record had allegedly assisted a burglar by driving him to the scene of his crime. Lawyers were there to argue whether the accessory should be held in jail, without bail, before her trial.

Alleged murderers and rapists are usually held without bail. People like the woman before Howard, so-called "habitual offenders" who have accumulated a string of lesser convictions, fall into a gray area. That the defendant had family members in the area would normally work in her favor.

But in Bennington County, lawyers say, there is no suspense in these cases: Prosecutors almost always seek hold-without-bail orders, and judges usually comply.

True to form, Deputy Bennington County State's Attorney Robert Plunkett asked that the woman be held without bail pending her trial — which could be a year or more away — and Howard complied. She was sobbing when court security guards led her away.

"They don't have that ability to look at a case and say, 'Just because I can say that person could be held in jail doesn't mean they should,'" said a veteran attorney who practices throughout southern Vermont. "It's jail, jail, jail."

The state's inmate population has more than doubled since the early 1990s, even as the crime rate in Vermont has fallen. Since 1993, Vermont has had hundreds more inmates than jail cells, necessitating a costly and controversial program of sending Vermonters to private, out-of-state prisons to serve their time.

In recent years, the Vermont Department of Corrections, which has a $130 million budget, has come under increasing pressure from lawmakers and criminal justice reformers to shrink its footprint and bring Vermont prisoners back home.

Efforts to reduce the inmate population have been focused primarily on two areas: Moving defendants out of the criminal justice system and into treatment, and reducing the number of defendants held in jail while their cases are pending.

But the department has little control over that, according to former DOC commissioner Andy Pallito. "Prosecutors have a much more measurable effect on the system than anyone else," he said, including judges, who tend to rotate to new counties every few years. State's attorneys choose which cases to bring and how aggressively to push for tough sentences.

Chittenden County incarcerates at a rate of 234 people per 100,000 residents. The incarceration rate is 325 in Rutland and 243 in Franklin. Bennington's rate is 509 per 100,000, according to 2014 figures from the DOC.

"We take what they give us," said recently installed DOC Commissioner Lisa Menard.

Marthage said she could not explain Bennington's high rate. But she implied that the DOC might be manipulating the figures to deflect criticism of the inmate population.

"It's difficult for me to comment on what the DOC numbers actually mean," Marthage said. "I have to take it with a grain of salt, because of who is collecting the numbers and what agenda they may have."

Vermont doesn't make it easy to analyze criminal activity town by town. The most recent data compiled by the Vermont Department of Public Safety is from 2012. It showed Bennington County with a slightly higher than average crime rate but almost twice the average incarceration rate, according to the DOC.

Former commissioner Pallito confirmed that the county had been an "outlier" since he started there in 1999.

"The main factor has been unreasonable state's attorneys and their deputies," said Saltonstall, who retired in 2014 after decades as a defense attorney in Bennington County. Now a resident of Arizona, he leaves water in the desert for migrants crossing the Mexican border. "A lot of these prosecutors don't have a good understanding of human frailty," he said.

Hard-Charging

Like their counterparts all over Vermont, Bennington County law enforcement officials have been busy dealing with crime related to Vermont's opiate crisis. Police in the southern county, which borders both New York and Massachusetts, are uniquely positioned to stop drugs from coming into Vermont from other states.

In 2013, that vigilance ensnared 27-year-old Shamel Alexander, an African American from upstate New York who arrived in town via taxicab. When police pulled him over, they found 11 grams of heroin on him. Even though he was a first-time offender, prosecutors recommended the maximum sentence of 10 years, and they got their way.

Alexander had served more than two of those years — among Vermont's out-of-state inmates in Michigan — when the Vermont Supreme Court overturned his sentence on February 12. Justices agreed that the police traffic stop and search may have been racially motivated.

So they ruled both inadmissible, threw out the conviction and sent the case back to Bennington County. Valerio and other legal observers expected prosecutors to file a perfunctory court document dropping the charge, which would lead to Alexander's release.

But weeks after the decision, he remained in the Michigan prison. Alexander's attorney, Bennington County public defender Jeff Rubin, filed a motion asking a judge to throw out the charge. Finally, late last week, nearly a month after the decision, prosecutors dropped the case.

Why didn't prosecutors do that after the Supreme Court ruling and free Alexander without instigating a legal fight?

"We have similar questions," Valerio said.

Marthage said her office was simply performing due diligence on the Alexander case. She also questioned how much Valerio, who as defender general supervises dozens of public defenders across the state, really knows about it.

"I'd love to know what exactly is the last actual involvement Matt Valerio has had in any court," Marthage said. "His people all file things for him. It's fascinating to me that it's so interesting to him, what happens in Bennington, when I've literally never seen him."

Valerio's office is actively defending another prisoner who has been a target of Marthage's office. Martin "Serendipity" Morales, who identifies as a woman, has been assisting fellow inmates with legal work at Marble Valley Regional Correctional Facility in Rutland. Most prisons and jails have a resident inmate who knows enough about the legal system to help fellow prisoners navigate it. Every Vermont correctional facility has a law library to facilitate that.

In early January, Bennington County prosecutors sent Lloyd Dean, a detective in the Bennington County Sheriff's Department, to interview several inmates from Bennington County who acknowledged that they filed appeals with the help of Morales, who is serving time for felony burglary and domestic assault. All three men said they had approached Morales for help and that she not been paid for her services. There is no evidence to suggest that any of the inmates believed she was a licensed attorney.

"She doesn't take payment for her work," Dean reported in an affidavit. "It's what she does. She enjoys it."

Nonetheless, on February 2, one of Marthage's deputies filed documents with the Vermont Supreme Court charging Morales with falsely representing herself as a lawyer and engaging in "unlawful practice of the law."

The same week, the Vermont Attorney General's Office briefly considered leveling the same charge against environmental activist Annette Smith. It decided not to, as Attorney General Bill Sorrell explained in a prepared statement: "Any definition of the practice of law must recognize the diversity of advocacy before different forums at the state and local levels, should not abridge First Amendment rights, and should ensure that Vermonters have access to justice."

Marthage declined to discuss the case against Morales in detail, but she did note a spike in the number of "post-conviction relief" petitions, aka PCRs, that Vermont inmates have filed asking for new trials or sentences or other relief.

"I don't charge people with being a nuisance," Marthage said. "I charge people with violating the law."

Same as the Old Boss

click to enlarge

- Holly Pelczynski/Bennington Banner

- Bennington County State's Attorney Erica Marthage

Marthage, 45, lives in tony Manchester with her husband and three young children. She was raised there, too, in more challenging circumstances.

"I was an endangered species in Manchester — I grew up poor," Marthage said. Her carpenter dad struggled with alcoholism, she said. Her mother earned money as a chambermaid — when she could find work. Neither parent had graduated from high school.

The youngest of five, Marthage was a mostly disinterested student at Burr and Burton Academy, which locals attend tuition-free, and occasionally got into trouble for cutting school. But she was determined to go to college and make a better life for herself. She spent her free time as a teenager volunteering at the office of a local attorney and became fascinated with criminal law. After graduating from the University of Vermont and then, in 1999, the University of Connecticut School of Law, Marthage worked as a prosecutor in Hartford, Conn. She left to be a deputy prosecutor in Bennington County, focused on juvenile cases.

In 2006, Marthage ran for state's attorney, challenging her old boss, former Bennington County state's attorney Bill Wright. He had a reputation as a tough-on-crime, law-and-order prosecutor. She pledged to be even tougher and decried the "insane" number of people who were placed on probation.

"Bennington County needs to have someone who shows a strong sense of responsibility to the community and instills faith in justice again," Marthage told the Bennington Banner.

At the same time, Marthage pledged to be "reasonable" and expressed an interest in working with nonprofits to treat addicts instead of incarcerating them. Many local defense attorneys who now criticize her said that's why they supported her successful 2006 campaign. "My focus as an office is on public safety, victim safety and offender rehab whenever possible," she said.

Marthage says her humble upbringing makes her sympathetic to many people who run afoul of the law.

"The most satisfaction I get out of what I do is when I get to help people who made a stupid decision on a bad day, something they hadn't thought about, and they just want to make sure they get a fair shake," said Marthage.

But Marthage's critics say she has too often thrown the book at the people she claims to be helping.

Opiate-related threats have come to dominate the agenda of Marthage and her four deputy prosecutors — although one of them, Christina Rainville, had been especially aggressive in pursuing alleged sex crimes before leaving the job last year.

"My only goal is to stop this waterfall," Marthage said of the opiate problem. "It's so bad, and so disturbing on so many levels."

Seven people have overdosed on heroin so far this year in the Bennington area. Salmon was the only fatality. Police quickly zeroed in on Trevor Shepard and his brother William, whom they had long suspected of dealing heroin.

William Shepard told police that he and his brother had brought heroin from Holyoke, Mass., to sell in Bennington, according to court documents.

A 27-year-old woman told police that, on January 31, she overdosed on a bag of heroin, labeled "American Gangster," that she bought from 26-year-old Trevor Shepard. When she recovered, she called him to complain about the negative effects, according to police affidavits. He warned her that some of the heroin that he was selling could be "laced" with fentanyl, a potent heroin additive that is highly lethal.

Another woman told police that, on February 1, she was with Salmon when he snorted heroin that he had bought from Shepard. Salmon overdosed and was revived with Narcan at a nearby hospital. The next day, Salmon bought more of the same heroin from Shepard. He died from a second overdose.

Marthage said Shepard's comments to the 27-year-old woman show that he knew the heroin he sold Salmon could be lethal.

"The affidavit lays out a factual scenario where the defendant is informing the potential user of the drug that this is pretty powerful stuff and you better be careful," Marthage said. "That provides a level of reckless disregard that is beyond a manslaughter charge. This is not just selling drugs."

But Shepard's attorney, Chris Montgomery, has asked a judge to dismiss the murder charge, which carries a maximum life sentence. Montgomery said in an interview that, using Marthage's logic, nearly every drug dealer in Vermont could be charged with murder should a customer die after willingly buying his or her product.

"It is highly unusual, and I've been doing this for close to 20 years," Montgomery said of the decision to file a murder charge. "I have never seen a defendant from our area accused of causing an overdose charged as second-degree murder. A lot of cases could fit in that charge of a person giving someone drugs."

County Fair?

Vermont has looked at the problem of unpredictable punishment before. In 2005, the legislature created the Vermont Sentencing Commission, a group of lawyers and experts charged with "reducing geographical disparities in sentencing," according to the law that created the group.

Its first — and only — leader was Michael Kainen, a Hartford attorney and former state representative who recently became a superior court judge.

The commission solicited a few reports about sentencing practices across Vermont and made an occasional presentation to the legislature. But the effort fizzled when the judiciary slashed its budget, and Kainen departed in 2008 for a job in private practice.

Though the commission remains codified in state law, it has not convened in at least four years, attorneys say.

"It never achieved its potential," said Robert Sand, who serves as Gov. Peter Shumlin's liaison to criminal justice programs. "I still think, conceptually, it's a good idea."

Sen. Dick Sears (D-Bennington), chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, does, too.

He served on the defunct commission. "Should you really have different sentences if you get caught passing a bad check in one county than another?" Sears asked rhetorically.

The longtime Bennington County senator was intent on clarifying two things: His legislative district earned its law-and-order reputation long before Marthage took office; in addition to prosecutors, local police and judges contribute to the culture.

And Sears is no less frustrated than southern Vermont defense attorneys that Bennington County continues to generate more inmates per capita than any other jurisdiction. Without mentioning Marthage by name, he said he hopes local prosecutors will come around to focus more on treatment and less on incarceration.

In the absence of a vocal sentencing commission, or laws that insist on some level of uniformity in charging and sentencing, individual state's attorneys in Vermont enjoy wide latitude in creating their own mini-criminal justice systems.

Sand, a former Windsor County state's attorney, should know. In 2007, he effectively decriminalized the possession of small amounts of marijuana in his jurisdiction when he stopped prosecuting those cases in criminal court and instead sent most people arrested for marijuana possession to a court diversion program.

"Every case is a blank slate, and the state's attorney fills that slate with their sentencing philosophy," Sand said. "I think it's reasonable for the legislature to say, 'We think there should be some greater measure of consistency.'"

Sand is now tasked with helping to establish treatment and diversion programs in all 14 counties, in hopes of reducing the inmate population and moving the state away from a traditional crime-and-punishment approach.

It's been slow going.

In 2014, after Shumlin devoted his entire State of the State address to Vermont's battle with opiate addiction, the governor and lawmakers set out to replicate Chittenden County's Rapid Intervention Criminal Court in Vermont's other 13 counties.

Created by Chittenden County State's Attorney T.J. Donovan, RICC sends repeat, nonviolent criminals with substance abuse or mental health problems to treatment, not court. If the defendants progress, Donovan never brings a case against them. Independent studies suggest that RICC has kept several hundred people out of prison in the past three years and reduced criminal recidivism in Chittenden County.

But programs such as RICC can only exist if the individually elected state's attorneys want them. To prod the prosecutors into action, the legislature pays for screeners — caseworkers who would interview defendants to assess their eligibility for a pre-charge program like RICC — in every county.

The response: State's attorneys in Addison, Lamoille, Washington, Rutland, Essex, Windsor and Orange counties created pre-charge programs.

In Bennington County, the screener is in place, reviewing cases and talking to defendants about their struggles. But there is no RICC-style program to refer them to. Regardless of what the screener finds, defendants go into the criminal justice system, as they always have.

Marthage says she supports the concept of a pre-charge program — in theory — but isn't sold on what's out there. She also worries that there aren't enough treatment options and counselors in Bennington County to support eligible defendants. "The tools in our toolbox are so limited," she said.

Local attorneys say the pre-charge programs don't exist because Marthage's office isn't interested in having them. For evidence, they point to the recent demise of the only alternative court program that ever got off the ground in Bennington County.

In 2007, the county launched a so-called "domestic violence court" that aimed to stop the cycle of spousal abuse. It forced defendants to undergo counseling and kept temporary restraining orders in place. By completing a treatment program, an offender could skip prison for probation, thereby accelerating the reunification process.

A study by the Vermont Center for Justice Research showed that the program cut Bennington County's domestic violence recidivism by about 50 percent, while reducing incarceration during the same period — between 2007 and 2010.

In 2015, the man who spearheaded the program — Bennington County Superior Court Judge David Suntag — retired. And the domestic violence court went with him.

Marthage pinned blame for the demise of the domestic violence court on the Department of Corrections, whose probation officers, she said, became increasingly rigid about allowing defendants charged with domestic violence the freedoms necessary to engage in treatment.

In lieu of a domestic violence court, Marthage said she has been aggressive in pursuing domestic abusers who fail to live up to the terms of their probation.

More specifically, her office files a minor criminal charge, "violating conditions of release," every time a defendant fails to check in with a probation officer, contacts the alleged victim, violates a curfew or runs afoul of any of the numerous regulations placed upon them by probation officers.

In a few instances, Bennington County prosecutors have filed more than 100 VCR charges against a single defendant. The county files VCRs at nearly double the state average, the Vermont Center for Justice Research found.

Each charge can lead to fines, revocation of probation and jail time.

"In other counties you wouldn't bring 138 charges," Valerio said. "Prosecutors would bring two and have an arrest warrant and go from there. Bennington has a love of that kind of stuff."

Marthage is unapologetic: "The idea that I'm somehow seeking out all these jail sentences— What am I, twisting the judge's arm? These are not things I accomplish by fiat." On her desk, she said, are "stacks of files" of cases she has elected not to pursue.

She said that doesn't sit well with her constituents, who want just the opposite: tougher justice than one of Vermont's toughest prosecutors is already meting out.

The original print version of this article was headlined "The Prosecution Never Rests"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Crime, Bennington, cannabis related, criminal justice system, Erica Marthage, incarceration, Law Enforcement

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Vermont Scrambles to Open Five Facilities for Homeless Residents by April 1

Feb 7, 2024 -

Lawsuit Accuses Burlington Police of Using Excessive Force on Black Teen With Disabilities

Jan 31, 2024 -

Burlington Council Moves to Declare the Drug Crisis a Top Priority

Sep 7, 2023 -

The Acting Chief: For Three Years, Jon Murad Has Auditioned to Be Burlington's Top Cop. Will He Finally Get the Role?

May 3, 2023 -

National Law Enforcement Experts Come to Burlington to Share Ideas on Police Reform

Feb 20, 2023 - More »

Comments (22)

Showing 1-10 of 22

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 2. Vermont Senate Votes Down Ed Secretary Nominee Zoie Saunders Education

- 3. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 4. High School Snowboarder's Nonprofit Pitch Wins Her Free Tuition at UVM True 802

- 5. Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State

- 6. Help Seven Days Report on Rural Vermont 7D Promo

- 7. An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News