Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

What's the Future of Vermont Philanthropy?

Published July 18, 2018 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated August 6, 2018 at 1:30 p.m.

Terry Pomerleau grew up eating breakfast and dinner most days with his grandfather, the late Burlington real estate tycoon Antonio Pomerleau. As a teenager, he chauffeured the shopping-mall developer and philanthropist from meeting to meeting and heard every story and aphorism a thousand times.

"My grandfather always said that you have to do what you love. You have to be passionate about it. Doesn't matter if you work with a pick and shovel," the 31-year-old grandson said last week at the Humane Society of Chittenden County in South Burlington.

Dressed in jeans and a button-down shirt, Terry bared his left forearm. "So after his passing," he said, referring to his grandfather's death in February at age 100, "I got a pick-and-shovel tattoo to remind me, every day, that you have to do what fulfills you."

What fulfilled the elder Pomerleau was cutting real estate deals and, later, writing seven-figure checks to Vermont nonprofits. What fulfills Terry, one of Tony's 13 grandchildren, is working for one of those charitable organizations.

Last November, after stints at Pomerleau Real Estate, a Volkswagen dealership and as a potter, he moved from the local humane society's board of directors to a full-time position as its development manager. Now he shares a small office with another staffer and a gray-and-white rescue kitten named Tyler.

Though Terry no longer works out of the family firm's iconic Greek Revival headquarters overlooking Lake Champlain, he sees himself as carrying on the philanthropic legacy of his famous forebear. In addition to his day job at the humane society, Terry serves on the board of the Greater Burlington YMCA, which has received millions of dollars from the Pomerleau family over the years.

"My grandfather raised me not to take over the company but to take over the impact that he has helped make on the community," Terry said.

While the Pomerleaus are no ordinary Vermonters, their experience reflects a broader trend: Millennials born in the 1980s and '90s are less interested in giving than doing. "Younger people want to have more of a connection than just making a donation," said John Sayles, CEO of the Vermont Foodbank.

They're also more focused on the measurable impact of their charitable endeavors than previous generations were, according to Montpelier philanthropic adviser Christine Zachai, and they're not married to the nonprofit model. While their grandparents may have supported a traditional community institution, such as a United Way chapter, younger philanthropists might "make a financial investment in a B corp that promises to bring clean water to Flint, Mich.," she said, referring to for-profit, socially minded benefit corporations.

"Millennials have a much higher degree of distrust of institutions generally, and they have very little loyalty," Zachai said.

Such developments pose a threat to Vermont's $6.8 billion nonprofit sector, which has long relied on direct mail, capital campaigns and fundraising events to pay for the critical services it provides. "I think everybody is nervous about trends in giving," said Vermont Community Foundation president and CEO Dan Smith. He advises nonprofit leaders to "be prepared for change."

The change isn't just generational.

Vermont's nonprofit leaders worry that new federal and state tax laws could reduce financial incentives for major charitable giving. They question whether increasingly popular philanthropic tools, such as bank-affiliated "donor-advised funds," could steer money out of state. And they wonder how to harness the continued growth of online giving as other fundraising mechanisms become less effective.

Most worrisome is that while charitable giving has increased nationally in recent years, the percentage of people donating has declined. "So philanthropy is becoming more and more elite," said Dan Parks, managing editor of the Chronicle of Philanthropy. It's also becoming less stable for nonprofits, because they're increasingly dependent on the whims of fewer, larger donors. (See accompanying profiles.)

According to Giving USA, an annual report by the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, the total amount contributed to charity increased by 5.2 percent year over year in 2017, with nonprofits taking in a total of $410 billion. But between 2000 and 2014, according to Lilly researchers, the percentage of households donating to charity dropped from 66 to 56 percent.

Aggie Sweeney, who chairs the Giving USA Foundation, attributes some of the shift to growing income inequality. Particularly since the start of the Great Recession a decade ago, many families that used to set aside money for philanthropy can no longer afford to do so.

"The hypothesis is that there are trends around debt, whether it's student or credit card, lack of savings and lack of financial security making people less comfortable with the possibility of giving," explained Smith of the Vermont Community Foundation.

Meanwhile, Vermont nonprofits have lost out on some reliable corporate contributions. When GlobalFoundries acquired IBM's Essex Junction plant in 2015, it put a halt to a generous employee match program that sent nearly $1 million annually to local nonprofits. The United Way of Northwest Vermont, a major beneficiary of that funding, has since pulled back its grant-making.

Along with threats, there are also opportunities — particularly for nonprofits that respond and adapt to changes in philanthropy. The Vermont Foodbank has focused on growing its digital presence in recent years and even launched a "peer-to-peer" fundraising tool modeled after popular crowdsourcing platforms, such as GoFundMe. The Vermont organization saw a 36 percent increase in online giving in 2017, according to Sayles.

"In some ways, I think that crowdfunding is a way to engage people in philanthropy and giving," he said.

While young people have limited means, Terry Pomerleau said, they're more likely to donate their time and energy to nonprofits. As he toured the humane society's busy facility — and greeted a pair of Scottish fold cats named Mr. Yin and Mr. Yang — he noted that the organization is run by 18 employees and 207 volunteers. "My grandfather used to say, 'Giving money is easy. Giving time is hard,'" he said.

Terry expressed confidence that his generation would eventually give its time and its money to charity. "I hope that millennials and younger step up, because it's on our shoulders," he said. "If we don't, no one else will."

Who Gives?

Vermont is home to more nonprofits per capita than just about any other state, and it boasts one of the nation's highest rates of volunteerism. But according to the Chronicle of Philanthropy, its residents give less to charity than those in all but four other states.

In 2015, according to the Chronicle's "How America Gives" report, Vermonters who itemize their tax deductions donated an average of $3,701. Mainers, who ranked last, gave $3,071, while Wyomingites, the most generous, gave $11,163.

These rankings don't reflect grassroots giving by lower-income individuals, because the Internal Revenue Service only tracks donations made by the roughly 30 percent of filers who itemize rather than take the standard deduction. Itemizers tend to be wealthier.

But, still: Why is Vermont ranked so low? A couple of possibilities: Those at the bottom of the list, such as Rhode Island ($3,092), New Hampshire ($3,313) and Hawaii ($3,650), feature high costs of living and low rates of religious observance. Those at the top, such as Utah ($9,621), Arkansas ($9,512) and Tennessee ($8,433), are quite the opposite.

According to Sweeney of the Giving USA Foundation, there's a clear correlation between religion and philanthropy — and not just because the observant are expected to tithe. "Many families and individuals learn about giving through their faith community," she said. "We see that those who are donors to faith communities are actually more likely to give to secular causes, also."

While middle-income itemizers in Vermont give far less per capita than other Americans, Vermonters earning more than $200,000 a year are closer to the national average, according to the Chronicle analysis.

That's consistent with what Vermont fundraising consultant Tere Gade has noticed in her work helping nonprofits raise money. In recent years, she said, there has been "a softening in the mid-tier donors," which she defines as those who commit to donate $25,000 to $75,000 over five years. What used to look more like a pyramid of donors, with the wealthiest on top, "is getting to look more like an hourglass."

Gade attributed some of that pullback to the "psychological poverty" even comfortable Vermonters feel in the face of national and global political changes; their fears, she said, dampen their willingness to give. (On the flip side, according to the Chronicle's Parks, President Donald Trump's administration has inspired new giving to abortion rights, civil liberties and media organizations.)

Of the $289 million that Vermont itemizers donated to charity in 2015, according to the IRS, more than a quarter, or $81 million, came from 450 Vermonters who earned more than $1 million that year.

The wealthiest don't just reach into their own pockets. Some control tax-exempt foundations funded by themselves, their families or their businesses. According to Seven Days' Vermont Nonprofit Navigator, 315 local 501c3 foundations reported combined assets of nearly $788 million in their latest filings with the IRS. While these organizations provide key support to Vermont nonprofits, they can also be fickle — as the interests of their founders and successors evolve.

One of the most prominent is the Lintilhac Foundation, a $19.8 million fund controlled by the heirs of Claire Lintilhac, the daughter of Canadian missionaries in China and wife of a businessman in the chemical and insurance industries. Founded in 1975 to establish a midwifery program at the hospital now known as the University of Vermont Medical Center, its mission has since shifted from women's health.

"I think we all feel that the foundation needs to follow in the direction of the skills and education and interests of the people running the foundation," said Claire's daughter-in-law, Shelburne resident Crea Lintilhac, who leads the granting enterprise with her husband, Phil, and their three adult children.

For Crea, who studied geology, and Phil, a plant science professor at UVM, that's meant refocusing the foundation on water quality, renewable energy and conservation. Of the nearly $963,000 it donated in 2017, according to a foundation report, five-figure donations went to a slew of environmental advocacy organizations, including the Conservation Law Foundation and the Vermont Public Interest Research Group.

The Lintilhacs even spent $45,000 to support a visiting UVM professorship for former secretary of natural resources Deb Markowitz and $58,338 to fund environmental attorney David Grayck's work on water quality and wildlife corridor land-use cases.

"There are not many scientists who have private family foundations," Crea said.

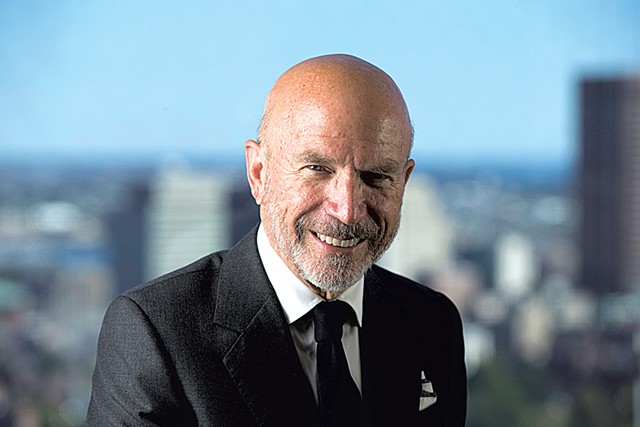

Rich Tarrant has a different philosophy about the foundation he created in 2005 with money from the $1.2 billion sale of his company, IDX Systems. He aims to spend it down and put the foundation out of business by 2044.

"My feeling is that when foundations and charities go on and on and on, the further they get away from the origination, the more likely they are to lose the value of the dollar and change their mission," he said. "I think you need to buckle 'em up sooner, rather than later."

Why 2044? "Because I'll be 98 then," Tarrant said with a laugh. "I don't want to wait to be 100 to get it done." He's making progress: In 2011, the Richard E. & Deborah L. Tarrant Foundation reported assets of nearly $12 million, according to an IRS filing. By 2016, they had dwindled to $6.6 million.

Tarrant still owns a house in Colchester but now lives in Hillsboro Beach, Fla., where Deborah serves as mayor. The vast majority of their giving goes to Vermont institutions, though the foundation donated to five Florida nonprofits in 2016.

Tarrant said he tries to run his foundation like a business, by maintaining a strategic focus on such priorities as education, workforce training and senior living. In 2016, it gave $65,000 to three Boys & Girls Clubs; $100,000 to UVM Medical Center; and $1.58 million to UVM, in part to fund a separate Tarrant Institute for Innovative Education.

"We don't wait to see what shows up in the mail," said Lauren Curry, who has served as executive director of the foundation since its founding.

Seventy-five-year-old Tarrant, who challenged Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) in 2006, is just as explicit about what he won't fund. According to the foundation's website, it's not interested in environmental or arts programs, nor "pro-choice or progressive political agendas."

In Funds We Trust

When Todd Lockwood moved to Vermont in 1977, the 27-year-old photographer was careful to hide the fact that he was, as he puts it, a "trust-funder." Lockwood's grandfather, Herbert Kieckhefer, had made a small fortune in a family business that pioneered the use of cardboard in shipping. Kieckhefer also invented — and patented — the milk carton spout.

Lockwood used his inheritance, along with money he'd made on a real estate deal, to build White Crow Audio, the iconic Burlington recording studio. But, for years, he refrained from making sizable donations to charity, because, he said, "I didn't really want to let the cat out of the bag."

"I think it's a sense of sort of existential guilt," he explained, "and there's this fear that people are going to judge you based on that."

Lockwood has since gotten over that fear and opened up his wallet. He suspects, however, that others like him donate less than they could — and he thinks that should change.

"My sense is that there's a segment of Vermont with inherited wealth who are giving way below their means to charity," the 67-year-old South Burlington resident said. "I think it's because they're trapped in social situations where it just wouldn't be cool to even acknowledge that that money exists."

Zachai, the Montpelier philanthropic adviser, works with many of the privately wealthy, who she insists give generously. "They want to be able to give back to their community and do the right thing and still be able to go to the grocery store and not have everybody know how much money they have and how much money they give away," she said.

Others are perfectly comfortable with — or even relish — being recognized. During his decades of philanthropy, Tony Pomerleau made donations to the Burlington Police Department, Saint Michael's College, the Greater Burlington YMCA and the Community Sailing Center that resulted in the naming of buildings after him and his family.

According to Terry Pomerleau, his grandfather believed that doing so would let other prominent community members know that "they need to do something."

"It was far less about him and more about putting other people on the plate," he claimed.

For those who are newly wealthy, it's not always obvious how to step up to the plate.

In December 2013, when a New York company agreed to buy Burlington's Dealer.com for nearly $1 billion, its founders became multimillionaires overnight.

Jill Badolato, then the company's director of corporate social responsibility, sprang into action. "I was like, I know a bunch of my friends just made money," she said. "I also began to realize that people didn't necessarily know how to give."

With $10,000 in company funds, Badolato organized a "philanthropic advising pilot." She chose 10 people who she assumed had made out in the deal and signed them up for four-hour sessions with Zachai and another philanthropic consultant.

Dealer cofounder and chief operating officer Mike Lane, then 38, was among the participants in the pilot. As he began to consider his future philanthropy, he took some advice to heart: "Try to invest in one or two things where you can personally see that you're working on something that has tangible results," he recalled.

Lane soon joined the boards of the Vermont Center for Emerging Technologies and Spectrum Youth & Family Services. At Spectrum, he spent hundreds of hours designing a program to help at-risk youth join the workforce. The idea was to establish a for-profit business within the Burlington nonprofit in order to employ and train Spectrum's clients. The result, a Williston car-detailing shop called Detail Works, launched in 2017.

"It's really a killer success story," gushed Lane, who is now 43 and no longer at Dealer. "We're working ... to teach them skills — not only how to detail a car, but also life skills, how to be employable."

Chasing Donors

Since 1986, the Middlebury-based Vermont Community Foundation has sought to encourage philanthropy within the state by advising donors, managing their charitable contributions and directing donations to vetted Vermont programs.

But as Smith, VCF's president and CEO, noted in a January 2017 letter to his board, national trends in philanthropy could change the way his organization does its job. He cited two particularly worrisome developments: the merger of two major online-fundraising organizations, GoFundMe and CrowdRise, and the success big banks had found replicating the work long performed by community foundations.

"Both had implications for the long-term trajectory of philanthropy nationally, internationally and, of course, in Vermont, too," Smith recalled. "So the question became: How do we ... respond to the changing ways that people are pursuing philanthropy?"

For those wealthy enough to donate tens of thousands of dollars to charity but not rich enough to establish their own family foundations, organizations such as VCF have long offered a mid-size option called the "donor-advised fund." Individuals can establish and donate to an account controlled by the Vermont Community Foundation, reap the tax benefits immediately and, later, recommend which local nonprofits should benefit from the investment.

In 1991, the Boston-based financial services firm Fidelity Investments adopted that same model and created a nonprofit spin-off called Fidelity Charitable. The latter would host donor-advised funds of its own and contract with its for-profit affiliate to manage the money.

By 2015, Fidelity Charitable had became the largest nonprofit in America, knocking United Way out of the top spot. In the fiscal year ending in June 2017, it raised nearly $6.9 billion through its donor-advised funds, according to the Chronicle of Philanthropy. That fall, six of the top 10 nonprofits on the Chronicle's "Philanthropy 400" list were affiliated with banks such as Goldman Sachs and the Charles Schwab Corporation.

When Lockwood established a donor-advised fund 20 years ago, he went with Fidelity. Lockwood moved $100,000 worth of stock to the account and has been donating the returns to charity ever since.

"It's like a mini-foundation," he said. "It's really a fantastic way to dabble in charity at a higher level than the average joe is probably used to."

Not everybody is happy about the rise of these bank-sponsored funds.

Because they're under the umbrella of massive nonprofits, such as Fidelity Charitable, it's impossible to divine from tax filings who is putting what in such funds and to whom the money is eventually distributed. "Nonprofits find them frustrating because they're so opaque," said Parks, the Chronicle editor.

And because account holders such as Lockwood receive their tax deduction at the moment they transfer money to such a fund — not when they later distribute it to a charity — there's little incentive for the latter step to take place.

In fact, Park said, because the Fidelity mother ship makes money investing Fidelity Charitable's assets, it has "an incentive for that money to sit there." Unlike traditional foundations, which are required by the IRS to spend 5 percent of their investment assets each year, donor-advised funds are not.

According to Nabil Ashour, a spokesman for Fidelity Charitable, the organization has a policy "that keeps folks granting" to charities. Account holders get a nudge to do so after three years of inactivity, and their accounts get "swept" into a general pool of contributions if they lie dormant for six years. In an average year, Ashour said, 20 percent of Fidelity's overall investment assets make their way to other charities.

The rise of these funds threatens not only organizations such as the Vermont Community Foundation but Vermont nonprofits more generally. That's because, unlike VCF, which advises its donors and encourages them to keep their charitable dollars in-state, Fidelity, as Ashour put it, is "a cause-neutral organization."

According to Smith, "The overwhelming majority of our grant-making occurs inside of Vermont." Only about half of the money doled out by Fidelity account holders stays local, according to Ashour.

"The difference is the underlying mission of the organizations that host the donor-advised funds," Smith said. "You worry, to a certain degree, that we're missing the opportunity to support the vitality of Vermont communities."

Heir to the Throne

Terry Pomerleau's first glimpse of charitable giving came when, as a kid, he attended his grandfather's legendary Christmas party for underprivileged children. For 37 years, the family patriarch hosted the holiday gathering at a Burlington hotel, where low-income Vermonters enjoyed a meal, gifts, and the opportunity to meet Santa Claus, state politicians and the Pomerleau clan.

"The days leading up to and following that event were the happiest my grandfather was," he said.

According to Terry's uncle, Ernie Pomerleau, the Christmas parties will go on — as will the family's philanthropy. "Dad's been the face of it, but the company has been the driving force," he said, referring to the family's real estate firm. "It's not going to change at all. Actually, it'll get bigger. It's something we feel committed to."

Ernie and two siblings, Pat and Alice, now run the Antonio B. and Rita M. Pomerleau Foundation, to which the family patriarch donated in his will. "We've done some stuff with estate planning," Ernie hinted, declining to provide more details.

Meanwhile, Terry is contributing in his own way.

In the basement of the humane society, he showed off a back room with washing machines and industrial sinks. "This is where the magic happens," he said. "Everyone wants to walk the dogs, but everyone has to start with dishes."

As he climbed a set of stairs to the first floor, Terry recalled a conversation he'd had with his grandfather not long after joining the humane society and shortly before Tony died.

"He was just like, 'I'm so proud of you,'" Terry recalled.

No doubt he'll remember that blessing each and every time he rolls up his sleeves.

Profiles in Giving

Bill and Jane Stetson

For Bill and Jane Stetson, philanthropy was never optional. Both halves of the Norwich couple came from families that demanded it.

Bill's great-grandfather, a North Carolinia pharmacist named Lunsford Richardson, concocted Vicks VapoRub and founded the company that would eventually sell NyQuil, Clearasil and Olay. Jane's grandfather, Thomas Watson, built IBM into the original computing powerhouse. Her father, Arthur, served as U.S. ambassador to France.

"I was brought up in a philanthropic household. It was an expectation," Jane said. "For me, it was like brushing your teeth in the morning or putting on your clothes. It was part of the psyche in my home."

As a young man, Bill was summoned to the family office in North Carolina and given access to a small amount of foundation money to donate to charity. "Over the years you'd be allowed more and more," he said. "You had to prove that you understood and you knew how to research a 501c3."

These days, the two give through a variety of family foundations and from their own pockets. They focus on the environment, medicine, education, film and whatever else motivates them in the moment. "I'm a highly compassionate person, so it doesn't take much to move me," Jane admitted. "If I see a need, I'm moved."

For a time, that need was Democratic politics. Jane raised more than $4 million for Barack Obama's two presidential campaigns, earning her the finance chairmanship of the Democratic National Committee and nearly the French ambassadorship. Now, she said, she's focused on gun control; she just joined the board of the advocacy group Gun Sense Vermont.

"I am rabid about getting some commonsense [gun laws]," she said. "I'm not against guns. I don't think hunting should be abolished. I just think we're an accident waiting to happen."

Both Stetsons say they've been attempting to give more money to fewer organizations. "You want to give them more of an oomph," said Bill, who has tried and failed to reduce the number of recipients from 50 or 60 to 10 or 15. "But it's really hard because, emotionally, you're attached to these organizations, and they call you and say, 'We're so sad that you're going to leave us.'"

"You really have to learn how to say no," Jane added, "which is a painful thing."

Carl Ferenbach

Young people aren't the only ones experimenting with new ways of giving back. At 76 years old, Carl Ferenbach is still trying to figure out how to make the most change with the fortune he's built.

A cofounder of the Boston-based private equity firm Berkshire Partners, Ferenbach and his wife, Judy, have spent time in Vermont since 1988, when they bought a farmhouse and 90 acres of land in Townshend. In 2000, he and real estate developer Rick Davis established the Permanent Fund for Vermont's Children, which seeks to expand access to high-quality childcare. Four years later, Ferenbach founded the High Meadows Fund, which focuses on environmental and land-use issues.

In both cases, Ferenbach sought to relinquish control of the organizations and let others lead the way — an approach he had taken at Berkshire Partners, which he characterized as a "partnership and collaboration" with no chief executive. "Nobody reigns," he said. "That just worked for us. And so everything I did [in philanthropy] was informed by that experience."

Ferenbach placed the Permanent Fund and High Meadows under the umbrella of the Vermont Community Foundation, which provides tax and management services and appoints a majority of the two organizations' board members. Even so, he faux-complained, VCF was "slow to understand" that he really wanted to let go. "Eventually we got through to them," he said. "'A day will come when you guys have this thing, because we won't be here. So we might as well make that day now.'"

Ferenbach's philanthropy doesn't end with traditional 501c3s. He established a corporation called High Meadows Associates to buy and conserve Vermont farmland and then sell it for less to young farmers. Though technically a for-profit entity, its goal is not to make money — and it doesn't.

Even Ferenbach's personal investments are chosen with an eye on something other than the bottom line. He estimates that 15 to 20 percent of his assets are invested in experimental clean technology and energy ventures that could make money but could also crash and burn.

"For me, it's just fun to understand what they're doing," he said.

As a lifelong investor, Ferenbach sees Vermont as an affordable place to "incubate" good philanthropic ideas to be replicated elsewhere. "A dollar goes about five times further here than it does in New York or San Francisco," he said. "We can do things others can't because it doesn't take a huge amount of money to do them here."

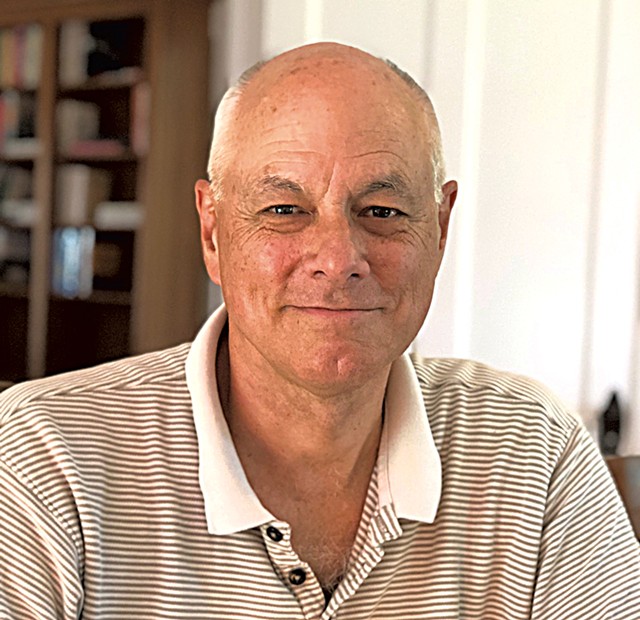

Buzz Schmidt

Buzz Schmidt decided to spend the final phase of his career testing his philanthropic theories in Vermont. In 1994, the Guilford native founded the groundbreaking transparency organization known as GuideStar. By posting nonprofits' annual Form 990 reports online for the first time, it enabled the general public to hold 501c3s accountable.

Schmidt has developed strong views about what works and what doesn't in philanthropy. Traditional private foundations, he believes, have become "moribund institutions" because they aren't accountable to customers, investors or regulators. "Perpetuity is a real wet blanket over creativity," he said. "The fact that you don't have to appeal to other people for money, forever, is a real impediment to institutional growth and progress."

At the Heron Foundation, an anti-poverty organization he chairs, Schmidt has experimented with a different approach. Instead of spending just the mandatory 5 percent of its assets on its mission, Heron invests 100 percent of it in nonprofits, for-profits and other entities that advance its goals. "If that means that, because of the risky investments we made, our capital declines and we go out of business, so be it," he said.

After returning to his hometown in 2013, Schmidt found himself tackling one of the toughest challenges of his career: saving Brattleboro's iconic but dilapidated Retreat Farm. Established in 1837, it was for much of its existence an "asylum farm" for the neighboring Brattleboro Retreat mental hospital. But by 2014, when Schmidt first considered taking over the 500-acre property from the Windham Foundation, the farm had fallen on hard times.

"I really fell in love with it and thought, Wow, this is an amazing community resource in a very nascent state," he said. Schmidt envisioned converting the farmstead into a nonprofit economic development campus that could host agricultural, educational and commercial ventures.

"I wanted to make a substantial contribution to the region," Schmidt said. "And I wanted to also test a number of hypotheses I had about how enterprises contribute to regenerative capital in a community."

Schmidt, who took over the property with a new nonprofit in 2016, has a ways to go to restore the Retreat Farm and achieve his vision. But, so far, he said, the experience has left him optimistic about the future of philanthropy in Vermont.

"I'm just really impressed by the potential we have to do things in policy and philanthropy and the combination of those here because of the size and because of the communication among players," Schmidt said. "We don't have that in other places."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Giving It Up"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Economy, Nonprofit Series, Philanthropy, Terry Pomerleau, Antonio Pomerleau, Todd Lockwood, Bill Stetson, Jane Stetson, Carl Ferenbach, Buzz Schmidt

More By This Author

About The Author

Paul Heintz

Bio:

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Speaking of...

-

Creator Seth Honnor on His Live Game Show/Social Experiment 'The Money'

Sep 21, 2022 -

Boys & Girls Club Awards More Than $100,000 in College Scholarships

Aug 2, 2021 -

Developer and Philanthropist Robert 'Bobby' Miller Dies at 84

Feb 5, 2020 -

Vermont Cops Partner with Nonprofits to Fight Sex Crimes

Jul 18, 2018 -

Search and Replace: Hiring New Nonprofit Leaders Isn't Easy

Jul 18, 2018 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 2. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 3. Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State

- 4. High School Snowboarder's Nonprofit Pitch Wins Her Free Tuition at UVM True 802

- 5. An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment

- 6. Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate News

- 7. From the Deputy Publisher: Winooski, My Town? From the Publisher

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis