Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

-

News

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont…

-

Housing Crisis

'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted…

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

- An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment 0

- Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

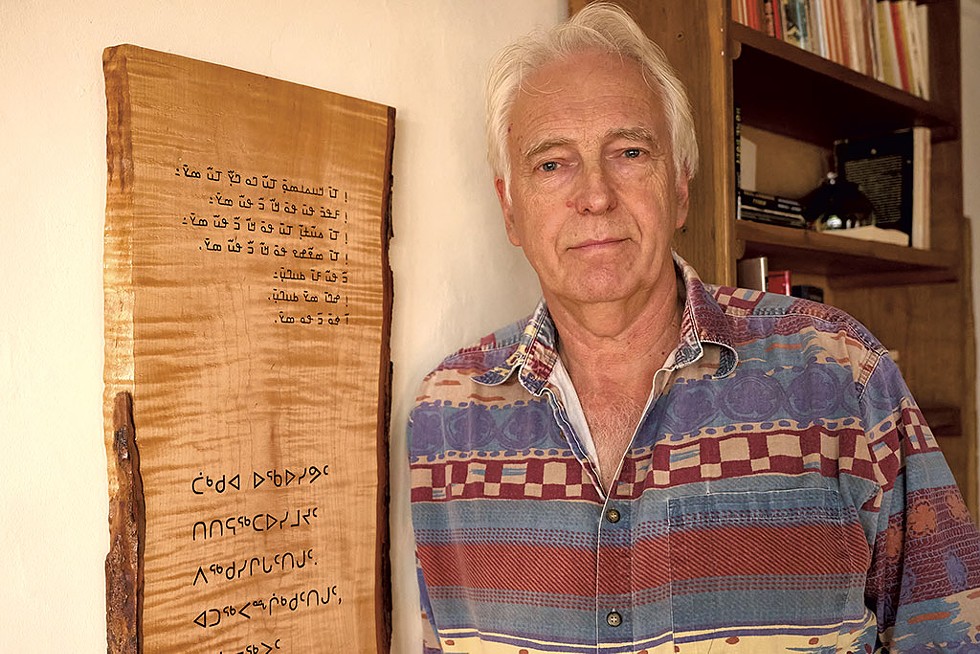

Writer Tim Brookes Creates Works of Art to Save the World’s Endangered Alphabets

Published December 15, 2021 at 10:00 a.m.

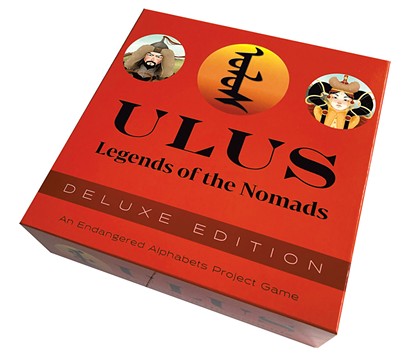

A handful of sheep knuckles rattled across the dining table like molars knocked loose in a barroom brawl. The dried yellow bones, called shagai, came to rest on a round felt mat resembling an astrological chart.

Around the mat's perimeter, eight letters hand-stenciled in Mongolian calligraphy spelled out the four seasons. Nearby, a stack of brightly colored playing cards bore elaborate illustrations of heroes, gods and monsters from Mongolian history and mythology.

The cards, mat and shagai are elements of Ulus: Legends of the Nomads, a multiplayer board game and latest creation from the inventive mind of Tim Brookes — British expat, longtime Vermont resident, writer, college professor, former NPR commentator and lover of words. The game is the product of his passion for the world's rare and beautiful alphabets, many of which, like Mongolian, are in danger of extinction.

Brookes is the one-man force behind the Endangered Alphabets Project, the nonprofit he founded in 2013. He has worked with scholars, activists and Indigenous peoples worldwide to document and share such threatened writing systems as the Afáka script of French Guiana, Takri of India and Naasioi Otomaung of Papua New Guinea.

Some of his efforts have been intellectual and scholarly. Brookes created the online Atlas of Endangered Alphabets and, just months ago, launched a campaign to establish a "red list" of alphabets — akin to the international Red List of Threatened Species — to highlight those scripts on the brink of disappearing.

Other work has been artistic and rooted in the physical. About a decade ago, Brookes took up wood carving, inscribing sinuous scripts into slices of Vermont maple that he exhibits as part of the campaign to raise public awareness about threatened letters and symbols.

His research into these unusual and often enigmatic writing systems raises larger questions, among them: What is the importance of an alphabet to the language it communicates — and to the people who created it? In short, what lies hidden within the myriad ways we humans write?

"When a culture is denied the chance to use its own traditional script ... within two generations everything written in that traditional script is lost," Brookes said. "It's incomprehensible to the very people who created it."

Ulus: Legends of the Nomads is many things. It's a game made, in part, by the Indigenous people of Southern Mongolia, an autonomous region within China. The game is also an elegantly rendered work of art and a meticulously researched representation of the Mongol Empire, which at its height stretched from the Korean Peninsula to Poland.

But at its heart, Brookes said, Ulus: Legends of the Nomads is a tool to help the people of Southern Mongolia resist the Chinese government's campaign to eradicate their culture.

"The Mongols defeated the Chinese, and the Chinese government is trying to rewrite history as though it never happened," Brookes explained. "The way to maintain control over a minority is to convince them that they're worthless."

Those who study the world's languages see great value in Brookes' efforts.

"When a spoken language dies that's never been written down, it's as if it has never been," David Crystal, an honorary professor of linguistics at Bangor University in Wales, explained by email. "Writing adds permanence, whether in an alphabetic system or any other. And that means we have access to the unique vision that a language expresses."

For decades, scholars have conducted research and fieldwork on endangered languages. Crystal, one of the world's preeminent language scholars, said that what was missing was an effort to raise awareness about their rapidly disappearing alphabets, too. Brookes' work — his website, art and games — is helping to fill that gap.

Brookes has no formal schooling in anthropology, foreign languages or alphabets, nor has he traveled to most of the countries where endangered alphabets are found. He speaks only a smattering of French and German — and can swear in Spanish, he said.

But having spent most of his life as a writer, journalist and storyteller, Brookes seems suited to the task of documenting and preserving humanity's multiform palette of letters.

"One of the great things about journalism is, you're paid to be curious and find out new things," Brookes said. "At the heart of every story is a mystery. If you haven't found the mystery, you haven't found the story."

'The Origin of Writing'

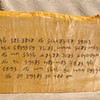

click to enlarge

- Bear Cieri

- Tim Brookes working on an Abenaki piece that reads "Please honor the pledge," which is directed to students in the Abenaki course at Middlebury College to speak Abenaki rather than English outside of class time

Brookes shared his own story in what he calls "the crow's nest," his attic office at the top of a tight spiral staircase in his home in Keeseville, N.Y. The 19th-century farmhouse, where Brookes has lived since January, overlooks Lake Champlain and offers stunning views of the snow-dusted Green Mountains. At dusk, the sun's amber glow reflects off the windows of Burlington, 10 miles to the east.

"I vowed that I would never again in my life live anywhere but Vermont," Brookes said wistfully, as he settled his 6-foot-3-inch frame into a desk chair on a recent morning. But his partner, Kristi Brennan, has work that requires her to live in New York, so after more than five years in a commuter relationship, Brookes moved from the Green Mountain State, which he'd called home since 1980.

"I feel as though I'm still in Vermont; I'm just at the end of a very long driveway that's prone to flooding," he said with the humor that characterizes much of his writing.

Brookes has written 18 books on subjects ranging from America's best-selling musical instrument (Guitar: An American Life), to a first-person account of living with a chronic respiratory disease (Catching My Breath: An Asthmatic Explores His Illness), to an ill-fated National Geographic assignment to report on weather forecasting in India during monsoon season (Thirty Percent Chance of Enlightenment).

It was that talent for astute observation that earned him a slot as a monthly commentator on NPR's "Weekend Edition Sunday" from 1989 to 2008. Regardless of the subject, Brookes can turn a phrase like a Ferrari on a country road.

In April 1993, he treated NPR listeners to a comparison of a Vermont rainstorm to one in Britain. Vermont rain, he said, "falls with a sense of purpose, even of drama. British rain, on the other hand, is a condition. It's not weather, but something between a recurring mood and a congenital disease."

In an August 1996 piece, Brookes described buying a rebuilt lawn mower from a trailer park resident: "He was a tall, handsome man in his thirties, I'd say, with thinning dark hair and a grin that came and went too easily, as if he oiled that, too."

An American might speculate that Brookes' way with the English language is at least partly the result of his British upbringing and University of Oxford education. He was born in London in 1953 to a family of modest means. His father's work led to frequent moves, and by the time Brookes left England at 21, he had lived in 18 different houses. That pattern continued well into adulthood, usually by choice.

"I was very easily bored," he explained. "I would feel very much in a rut or trapped if I was anywhere for more than a few months."

While still attending Oxford on government grants, Brookes crossed the Atlantic in the summer of 1973 to thumb his way around North America. His journey became the subject of his 2000 book, A Hell of a Place to Lose a Cow: An American Hitchhiking Odyssey, which the New York Times listed as one of the best travel books of the year. He played guitar throughout that trip, and in 2006 he wrote Guitar: An American Life about the crafting, history and role of the instrument in the U.S.

After graduating from Oxford in 1974, Brookes spent seven years traveling between England and the U.S. on various work-related and romantic adventures (he has been married three times and has two grown daughters). "None of the important decisions of my life have been made on the basis of facts or information," he quipped.

In 1983, after losing a part-time instructor job at the University of Vermont, Brookes began writing music and film reviews for a Burlington alt-weekly, the Vanguard Press. He found he had a knack for the work, perhaps thanks to the British educational system that tested knowledge through essay writing.

"I was used to taking everything I knew about any given subject and, in 45 minutes, putting it together with a beginning and an end," he said. One week, he wrote nine stories for the Vanguard.

As a freelancer, Brookes honed a writing style that would come to define his books, first-person narratives and Dave Barry-style radio commentaries.

"Tim wrote some of my favorite sentences ever when he wrote for the Free Press," said Candace Page, then an editor of the Burlington daily, who hired Brookes as a features writer after his stint at the Vanguard. "It didn't matter what the subject was, you wanted to read the story because Tim had written it," said Page, who is now a consulting editor at Seven Days.

After leaving the Free Press, Brookes cobbled together an income as a freelancer until Vermont Public Radio hired him to produce its program guide, which at the time was little more than a monthly calendar. Brookes turned it into a magazine called North by Northeast, which featured original writing and artwork from around the region.

Brookes, who taught writing, literature and composition on and off at UVM throughout the 1980s and '90s, landed at Champlain College in 2006, where he became director of the professional writing program.

In the late 1980s, he met an independent radio producer who enjoyed his writing and recommended him to her NPR producer, who was seeking a smart, funny commentator.

Brookes submitted samples of his film and music reviews, which were often offbeat, witty and irreverent. One review he wrote as a single long sentence. Another he penned in sentences of no more than three words to reflect the film's short, choppy editing. Brookes once found a movie so awful that instead he reviewed the Kit Kat bar he had eaten in the theater.

Soon, the commentator gig expanded to include monthly NPR commentaries.

Brookes' contrarian voice didn't always go over well. In the early days of the first Iraq War, when American cable news was dominated by videos of U.S. air strikes on Iraqi buildings, Brookes penned a tongue-in-cheek opinion piece about the Iraqis' temerity in firing back Scud missiles, most of which either missed their mark or exploded midair. He titled his commentary "Scuds against the '80s."

NPR's vice president of news heard Brookes' piece before it aired and promptly scuttled it.

"I was, of course, in the doghouse for doing it," Brookes said. He didn't lose his NPR gig but was moved to "Weekend Edition Sunday," which actually gave him more airtime and creative license. In all, Brookes produced about 250 commentaries for NPR, including coverage of the 1989 Velvet Revolution in Prague.

"It was quite a time," he recalled with a satisfied smile.

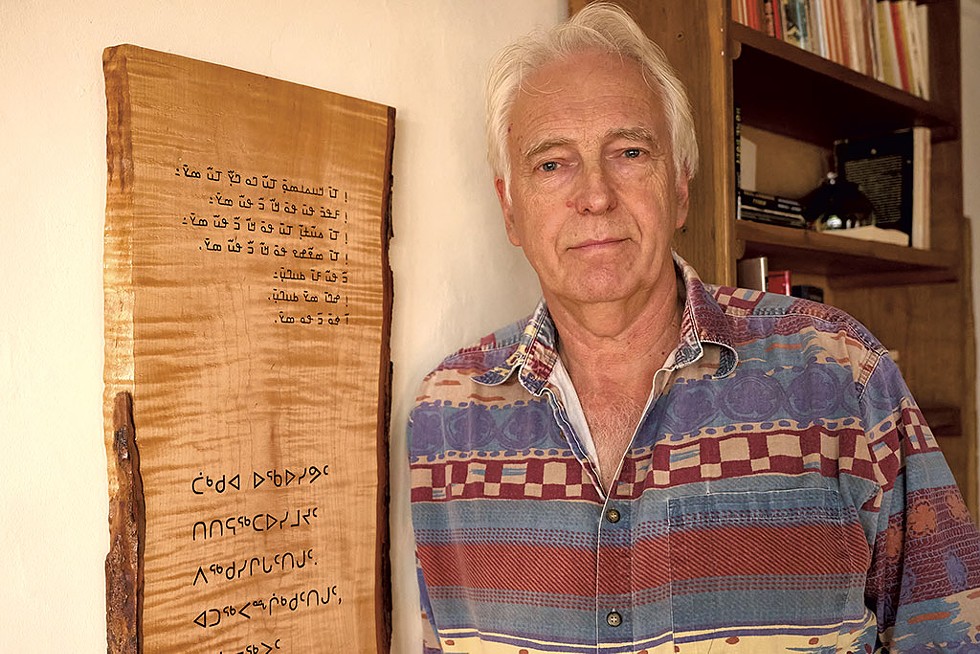

Carving a Niche

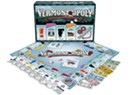

click to enlarge

- File: Matthew Thorsen ©️ Seven Days

- A carving from 2014 that says "Happy New Year" in Mongolian

In 2009, Brookes' passion for words took another turn. He began carving letters into wood as Christmas presents for his family members to hang outside their homes, offices and bedrooms. His early attempts, using the Latin alphabet, proved surprisingly difficult.

"The Latin alphabet has been more influenced by the mechanical process than any other," he said. "Consequently, it consists of shapes that are inimical to the human hand."

The Latin alphabet is "the one that won ... because it had the most lawyers, guns and money," he said, quoting a Warren Zevon song. Latin traveled with military and religious conquests for so many centuries that it's now the primary or secondary script in three-quarters of the world's countries. Consequently, those who use it are largely incapable of seeing anything in it beyond its utilitarian value. It has become, in Brookes' words, "linguistic duct tape."

The carved gifts were a hit, and, excited to find more characters and symbols to inscribe, Brookes chanced upon a website that changed his life: omniglot.com. The site aims to document all of the world's writing systems, past and present, living and extinct, real and fictitious.

Brookes was astounded to discover that, while there are more than 6,000 extant languages in the world, there are just 130 to 140 written alphabets. As many as one-third of those scripts are disappearing because they're not taught in schools, are forbidden by their governments, or are used by only a small number of elders and religious leaders, sometimes for secret rituals or sacred texts.

Brookes found many of the alphabets' calligraphic flourishes more expressive than Latin letters and thus easier and more pleasurable to craft.

To demonstrate, he pointed to a carving in Nüshu, a script from China's Hunan province and one of the world's few forms of calligraphy created by and for women. Its fine, threadlike lines resemble embroidery.

"Concealment was part of its very identity," Brookes explains in the Atlas of Endangered Alphabets. "This fact underlies almost every aspect of Nüshu — not just because women were not permitted to learn to read and write, but because it was used to capture and communicate aspects of women's lives that were also personal, private or secret."

Brookes found another advantage to carving scripts he couldn't read. If one stares at a letter or symbol long enough without knowing its sound or meaning, he said, one begins to recognize in it the human hand that created its graceful curves.

In other words, it becomes a work of art with its own intrinsic value and meaning.

Brookes treats them as such. The modest wall space in his house is dominated by his finely crafted pieces, which feature enigmatic characters etched into slabs of Vermont maple with the bark still attached.

Brookes gazed at one vertical carving of geometrically shaped letters — Aboriginal syllabics used by the Cree, Inuktitut and Ojibwe of northern Canada.

"To me, this looks like the origin of writing," he mused about the inscriptions, which are reminiscent of prehistoric cave drawings. "It's like some god split open this tree, and writing was revealed inside it."

Some of the alphabets resemble pictures but are really ideograms. Like emojis, they are symbols that represent not just words or phrases but also complex ideas.

The ideogram aya, which Brookes etched from the Adinkra symbol system of Ghana, looks like a fern that flourishes throughout the West African country. But the ideogram compresses scads of information into one symbol — in this case, resilience and resourcefulness, Brookes said.

Ideograms, he explained, "have been regarded traditionally in the West as childlike because they're pictorial, as though our alphabet were superior because it can be used to express abstract thought," Brookes explained. "But the very resurgence of ideograms, such as on road signs and emoji, show that we actually want that."

Another wall carving, called a pamada, is a Balinese symbol. Neither word nor letter, the symbol announces, like a trumpet fanfare, that the text that follows is sacred.

"It means that you need to read this differently ... with an open heart, with less haste, with a more reflective sense of purpose," Brookes said. "I realized that these are instructions for bringing out the best in a writer."

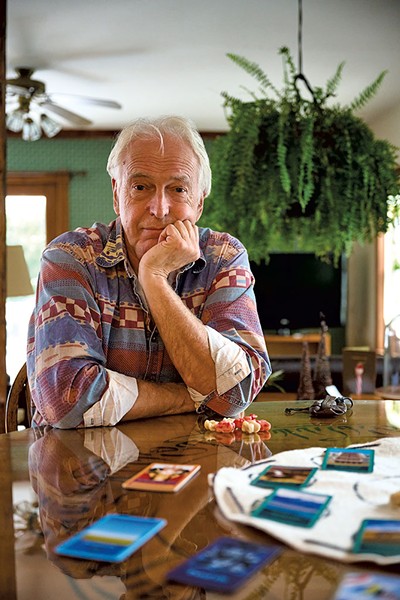

Gods and Monsters

click to enlarge

- Bear Cieri

- In 2010, Tim Brookes carved 13 versions of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

Energized by the omniglot.com trove of beautiful symbols, Brookes set out to obtain translations from researchers, scholars and Indigenous people of a single phrase in as many different alphabets as possible. He chose Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which reads: "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

Some alphabets used in the translations were very mathematical and geometric, he found, while others, such as Baybayin, native to the Philippines, were thin and reedy and required that he use his smallest carving tool. He assumed that some scholar had already discovered why the alphabets were so different. Not so.

"This is where it helped that I was not a linguist," Brookes said. "A linguist will look at an alphabet and ask, 'What rules of language does this script obey? What do I learn from it about the spoken word? Did this descend from something else?' I was asking, 'Why does it look like this?'"

As he discovered from an anonymous Spanish account from 1590, Baybayin scribes didn't write with ink but cut the surface of bamboo bark with the tip of a knife or sharpened iron, then rubbed ash into the thinly incised letters to make them stand out.

Brookes' Article 1 carving project, begun in early 2010, proved more time-consuming that he had expected. Recognizing that the temptation to quit would be powerful, he committed himself to displaying his works in May 2010 in the Champlain Mill in Winooski. In all, he carved versions in 13 different alphabets. His exhibit was well attended and attracted media attention.

"Tim is just a really inventive guy ... and he's a storyteller at heart," said Warren Baker, who worked with Brookes as a professor in the professional writing program at Champlain College. "That ties right into what he's doing now with the endangered alphabets and his love of the language. It's a noble and necessary pursuit."

Among others who attended Brookes' exhibition were several stonecutters from Barre. They suggested he try carving in stone, Brookes recalled, and emphasized the importance of the work he had undertaken.

"That was the first time I thought of this [project] as anything but documentation," Brookes recalled. "So if it's art, what do I do with it now?"

Ulus: Legends of the Nomads became one answer to that question.

For centuries, the traditional script Mongol Bichig was the universal alphabet of the Mongol people. In 1946 it was replaced by the Cyrillic alphabet currently used by the independent nation of Mongolia. Southern Mongolia is the last place where Mongol Bichig is used — and it is rapidly falling into disuse there.

In September 2020, Brookes read about the Chinese government's ongoing campaign to, as he put, "emasculate the Indigenous populations of China." Henceforth, schools in Southern Mongolia would be required to teach Chinese rather than Mongolian. A government-subsidized historical exhibit about the region, due to open in France, was forbidden from mentioning Genghis Khan, using the word "Mongol" or even referencing the Mongol Empire because of its conquest of China in the 13th century.

Around the same time, Brookes saw a photo on the website of the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center in New York City. The image showed a Mongolian boy at a protest holding up traditional Mongolian calligraphy. It read, "A foreign language is a tool. Our mother tongue is our soul."

As soon as Brookes saw that photo, he said, he knew he'd carve those words, though he was unsure what he would do with the carving. He considered presenting his work to the Mongolian embassy. Still, that gesture didn't seem sufficient.

"I knew this one-person nonprofit was going to take on the Chinese government," he said. "It just became a question of how."

Brookes sought the advice of a friend from Poland who had lived for years under Communist rule. The friend warned Brookes not to do anything that would enrage the Chinese government and worsen conditions for the Southern Mongolians. Instead, he suggested doing something that would help document and preserve elements of Mongolian culture. He suggested creating a game.

Brookes had invented games before but never one imbued with such significance. So he drew in Jovan Ellis, who had written his master's thesis at Champlain College on how games and interactive media can help preserve dying cultures. Brooks had been his thesis adviser.

"I always thought the Endangered Alphabets [Project] was fascinating," Ellis recalled. What began as a single chat about a board game turned into more than half a dozen consultations on game development. Ellis shared his research and game design philosophy, as well as his suggestions for translating Brookes' ideas into a physical medium.

In their efforts to preserve Mongolian calligraphy, Brookes and Ellis were determined to avoid cultural appropriation or tokenism.

"What Tim was really mindful about with this project was not making it a game about Mongolia and its people, but making it a game from Mongolia and its people," Ellis said.

To that end, Brookes sought guidance from Amgalan Zhamsoev, a professor in Russia and a teacher of Mongolian calligraphy. Tamir Samandbadraa Purev, whom Brookes called one of the most famous living Mongolian calligraphers, also provided advice.

Ellis described Brookes' approach to game design as "extraordinarily humble." Brookes would let go of his own ideas about how the game should be played if they didn't work from a game-design perspective, he said.

In the latter stages of the game's development, Tselmegtsetseg Tsetsendelger, a Mongolian American woman who lives in the U.S. and promotes traditional Mongolian culture, reviewed the rules of the game and suggested further changes that would more accurately and authentically depict Mongol culture.

"Ignorance often can be painted as a bad thing. Ignorance isn't the enemy, especially when you're doing cultural projects. Arrogance is," Ellis said. "Tim understands that it's OK to be ignorant and talk to people who know more about your project than you do."

For the game's artistic design, Brookes enlisted two Mongolian and two American illustrators. Burlington designer Alec Julien, who had worked on the redesign of two new editions of Brookes' books and on other aspects of the Endangered Alphabets Project, turned those illustrations into the games' playing cards.

"Tim is a dynamo of energy and ideas, and some of us have just sort of gotten swept up in his expansive magnetic field," Julien wrote by email.

Designing the look and feel of the game posed considerable challenges for Julien, particularly grasping the history and culture of people about whom he knew little. Another was working with a completely foreign alphabet.

"Imagine trying to check for misspellings when you can't read the language," he said.

"The far-flung teams that Tim puts together are always challenging to keep in touch with and keep to deadlines. And, of course, money's always tight," Julien added. "I'm still not quite sure how I've become so enmeshed in the Endangered Alphabets Project, though I'm damn happy I am!"

Brookes launched a Kickstarter campaign in 2020 to raise $20,000 to fund the creation of Ulus: Legends of the Nomads; the effort raised more than $37,000. Donors began receiving versions of the game in late September.

The standard version of the game sells for $55; the $125 deluxe version comes with a felt game board handmade by craftspeople in Southern Mongolia, a box of illustrated playing cards and 25 shagai, made from the bones of Vermont sheep. There's also a "vegetarian" version, made with plastic shagai, Brookes noted. The game cards and rule books are printed in the U.S., but the felt game mats — made from the same material the Mongolians use to make clothing and yurts — are hand-stenciled in a village outside Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia.

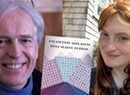

This week, Brookes traveled to New York City to present the game to Enghebatu Togochog, director of the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, and to play it with him and other Mongolian exiles who fled Chinese persecution. Brookes also gave the director the wood carving of the Mongolian boy's protest sign. Togochog seemed excited to see the game for the first time.

"Mongolian communities in the United States, especially the Southern Mongolians, are extremely grateful to Tim for his effort to raise awareness of the human rights conditions of Southern Mongolia through his game," he wrote by email. Togochog referred to China's current ban on Mongolian language and calligraphy as "cultural genocide."

Preservation or Exploitation?

click to enlarge

- Courtesy

- Tim Brookes presenting his wood carving to Enghebatu Togochog, director of the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center

As a white man of British heritage, Brookes is acutely sensitive to the perception that his work at the Endangered Alphabets Project could be perceived as cultural appropriation.

In 2016, Brookes said, he worked with Julien; Melody Mackin, an Abenaki educator, activist and artist; and other citizens of the Elnu, Missisquoi and Nulhegan bands to create a script that incorporated motifs from Abenaki artwork.

Then, in January 2019, Brookes was at the Vermont Statehouse presenting his Abenaki carvings when he received "a very valuable talking-to" by some Abenaki women asking whether he should be carving Abenaki letters. Though the women didn't tell Brookes to stop, he recalled, "They asked, 'How can you justify putting something in writing that was traditionally an oral language?'"

It was a fair question, and one he hadn't previously considered. As Brookes pointed out, the written word can be a particularly sore point for Native Americans because the U.S. government has used the absence of documents such as treaties, deeds and family records to deny tribes their rights and land claims.

But Brookes' goal has never been to profit from a culture by putting its letters on beer mugs or T-shirts. Rather, he has tried to spread the message that the Abenaki and other marginalized people wished to share: "We are still here."

Mackin, past chair and vice chair of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, described Brookes as a "wonderful ally to our community." Brookes has produced carvings for several Abenaki bands, created playing cards using their alphabet and helped develop an Abenaki font.

"He always asked, 'What can I do for you? What do you need?'" Mackin added. "Tim is a go-getter and a wonderful friend to have. I cannot speak more highly of him."

Crystal, the language scholar from Wales, now serves on the advisory board of the Endangered Alphabets Project. In 2010, Brookes sent him a wood carving of the Welsh proverb Cenedl heb iaith, cenedl heb galon, which means, "A nation without a language is a nation without a heart."

Crystal, author of two encyclopedias, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language and The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, said that Brookes' work is vitally important to raising public awareness of this alphabet extinction.

"Go into the street and ask people — as I did for a radio programme once — if they're aware of the ecological crisis affecting plants, animals, etc., and all will say yes," he wrote in an email. "Ask if they're aware of a language crisis, and almost all will say no."

It's not just the aesthetic dimension that is lost if these alphabets disappear, Crystal wrote. Also lost is the intellectual dimension, "because they can be the only way that we have access to how the users think about the world in their myths and legends, their knowledge of landscape and the balance of nature, the medical value of plants, and so on.

"Imagine what would be lost if Latin had never been written down, or, for that matter, English," he added. "That tiny language in the middle of a jungle somewhere also has a lot to tell us, if we can get at it."

On rare occasions, Brookes gets to make such excursions. Once, during a trip to Morocco, he met a group of people of Amazigh heritage. This largely nomadic people of North Africa, who once ranged from Egypt to the Canary Islands, have their own writing system.

During the 1960s, he explained, a group of intellectuals designed an Amazigh flag featuring horizontal stripes of yellow, green and blue. Each color corresponds to an aspect of their territory: blue representing the sea, green for the fertile lands, yellow for the vast desert.

In the heart of the flag, Brookes said, is the letter yaz, which resembles Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man. It's an iconic letter in their alphabet, he explained, revived from a writing system carved into desert stones 2,000 years ago. That one symbol seemed to encapsulate a universal theme in Brookes' work.

"It says, 'We have been here all along,'" he said. "'We have been pushed aside, we have been beaten and shot, but we were here first. And this is who we are.'"

How to Play Ulus: Legends of the Nomads

About 800 years ago, Genghis Khan (1162-1227) united the nomadic tribes of the Mongolian plateau to create the largest contiguous land empire the world has known. But as Khan and his descendants conquered huge swaths of Asia, Europe and the Middle East, they faced an existential question: What kind of empire should they create? Should it be urban or nomadic — based in a great city or in their people's traditional traveling existence?

The game Ulus: Legends of the Nomads stages a fictional but culturally accurate version of this question. Ulus is a Mongolian word meaning "land" or "nation," and in the game, each of seven gods has a plan for what should be done with Ulus, the Mongol lands. Etügen Eke, the Earth goddess, for example, wants an empire based on herding, farming and self-sufficiency. Tengri, the sky god, prefers one based on manufacturing, trade and commerce. Mergen, the deity of abundance and wisdom, wants one oriented around scholarship and wisdom.

Players choose a god card at random but don't reveal its identity to the other players. Each player then selects a champion card, which the other players can see, to achieve their god's aims. All the gods and champions are derived from Mongolian history and/or mythology.

The object of the game, played by two to six players, is to achieve a god's vision of Ulus by defeating monsters, trading and accumulating asset cards, and winning traditional Mongolian games of chance.

The first part of the game is nomadic in nature: Players move around a circular felt game mat from one season and sacred site to another. Each player gets four shagai, or dried sheep knuckles, whose four sides represent a goat, a sheep, a camel or a horse. But unlike dice, the shagai faces are irregular, making some faces harder to roll than others.

In the first half of the game, players toss the shagai like dice to move their champions from site to site, defeat monsters and win assets such as prayer flags, Tibetan mastiffs, snow leopards and shamanic drums. Some assets benefit all gods equally; others help particular gods.

After the champions visit all the sacred sites on the board, players move them to the center of the mat for the game's second phase, called Naadam. At Naadam, or annual summer festival, players compete in mini games that represent three Mongol sports of wrestling, horseback riding and archery, as well as storytelling. All the mini games are based on authentic shagai games of chance and fortune-telling and are played by tossing or flicking the shagai like jacks or marbles. Whichever player ends the game with the most points wins.

While the first half of the game is strategic, the second is more about dexterity, making the game a fair competition among people with different levels of gaming knowledge and experience.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Culture, Tim Brookes, Ulus, Legends of the Nomads, Endangered Alphabets Project, board game, alphabet, Video

About The Author

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

find, follow, fan us: