Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Bitters Dispute: Federal Regs Force Changes at Urban Moonshine

Published November 18, 2015 at 10:00 a.m.

Six years ago, Jovial King was a stay-at-home mother peddling kitchen-brewed bitters and tonics to sometimes-skeptical patrons at the Shelburne Farmers Market. She has since grown her hobby business into a million-dollar operation that runs out of a cramped laboratory on Burlington's South Champlain Street. Beakers and Buddha statues can both be found at Urban Moonshine, where 20 employees prepare herbal brews for more than 1,000 accounts across the country, including the Whole Foods grocery-store chain.

Run by earnest hippies who source their certified organic echinacea locally, Urban Moonshine has little in common with the obscure purveyor of Reload, a so-called herbal supplement that recently left NBA star Lamar Odom in a coma. The sexual enhancement product illegally contained the active ingredient found in Viagra, which might have interacted with other drugs Odom consumed that night.

But Urban Moonshine's maple bitters and Reload have been subjected to the same federal regulations.

King was calm on the September day an inspector from the federal Food and Drug Administration dropped by Urban Moonshine unannounced to comb through file cabinets, inspect floor drains and scour daily logs of who had mopped the floors when.

She left him alone to lead a reporter to a cavernous warehouse in the same building — formerly a refrigerator storing thousands of pounds of Cabot Cheese — where the company has plans to expand. The flaxen-haired King talked of "revolutionizing" the medicine cabinets of the masses with high-quality herbs. Chief herbalist Guido Masé, who has frizz-less dreads and a distance runner's build, pointed to where vats of herbs would soon be steeping.

The duo isn't worried about finding customers for their products. More Americans are turning to alternative capsules, tonics and tinctures for their ailments. The dietary supplements industry — a broad category defined by Congress that includes vitamin C, chamomile tea, protein powder and weight loss pills — is booming, accounting for more than $35 billion in sales last year.

But King and Masé are increasingly concerned about attracting the negative attention of federal regulators.

That mid-September visit wasn't the first time an FDA officer had dropped in on Urban Moonshine. In November 2014, the FDA put the fast-growing company on notice after discovering problems with how it identified herbs and documented the process of turning them into extracts.

King and her employees put in countless hours and spent tens of thousands of dollars to fix the issues. She hired lawyers and consultants to help her parse the legalese. Her herbs underwent a battery of chemical tests at professional labs. She signed a 10-year lease on a much larger, more suitable production space.

So King was expecting a clean report card when, three weeks later, she got the bad news: The inspector found 10 transgressions that could potentially shut Urban Moonshine down.

Michael McGuffin is president of the American Herbal Products Association, which represents roughly 250 growers, manufacturers and purveyors of botanical and herbal products. He noted that the FDA has been visiting a number of small operations, which he considers "bona fide herbalists making incredibly good-quality herbal tinctures."

Like his members, he is concerned that the stringent regulations could squeeze out small companies such as Urban Moonshine.

"It's an impossible situation," said Rosemary Gladstar of Barre's Sage Mountain Herbal Retreat Center. "The laws have to be changed, so it's not one-size-fits-all."

Raised on Tinctures

There's nothing new about herbal medicine. Asian cultures have embraced it for centuries — and still do. But the United States has been less receptive. Modern-day herbalists blame the American Medical Association for pushing their ancient craft underground by extirpating herbal remedies from medical school curricula in the early 20th century.

Exile turned out to be a mixed blessing: It stunted herbalism's growth but also delayed the arrival of stifling regulations. In Europe, herbs are classified as drugs.

Gladstar has been a practicing herbalist for approximately four decades and runs a 500-acre botanical preserve. Known as the godmother of American herbalism, she traces the herbal revival to the back-to-the-land movement in the 1960s. Herbalism, she theorizes, continued to gain converts as more people lost faith in conventional health care and started to care about healthy, organic food.

King studied with Gladstar after her own alternative upbringing in remote Bakersfield, where she lived with her parents in an off-the-grid geodesic dome with no running water. Herbal tinctures had always been part of her diet, so when she started selling her tonics at the Shelburne Farmers Market, she was taken aback by people's distrust.

"I really had my bubble burst," she recalled.

But King noticed that her digestive bitters didn't carry the same stigma, because people were accustomed to consuming them in cocktails. The manhattan, old fashioned and Rob Roy all contain the root-and-herb combo.

"My passion is really health and wellness, but I realized I could float my business on selling bitters to bars and cocktail enthusiasts," she said. She incorporated a year later, on the cusp of the craft cocktail craze. King still has the stack of news clips her product garnered; even Martha Stewart took note.

Before launching, King changed the name of the business from Ancient Earth Medicinals to Urban Moonshine, to appeal to bartenders and hippies alike.

The moniker also captures the company's mission of bringing wild medicinal herbs into cities, Masé added. The accomplished herbalist grew up in Italy, foraging in the Alps for wild mushrooms and bilberries. At age 14, he moved with his family to Kansas City, an herbal desert by comparison. Masé enrolled at Wesleyan University but left to pursue herbalism. Years later, he settled in Montpelier, where he helped found the Vermont Center for Integrative Herbalism, which serves as a clearinghouse of sorts for local herbalists. King was one of his students.

Masé helped King refine her product line. With no college degree or business experience, she built an enterprise, growing revenue by 50 percent each year until gross annual sales surpassed $1 million.

In an elegant black jumpsuit with gold earrings and a necklace, King noted without self-consciousness that her father was a street performer known as Orbit the Juggler when he met her mother, an astrologer, on Main Street in Burlington.

Peter King also popularized the tiny-house movement in Vermont. While he's been surprised by how quickly his daughter's business has grown, he noted, "She's still a hippie at heart."

Pure Intentions

In 1994, Congress defined a broad new category called dietary supplements — encompassing vitamins, minerals, herbs, amino acids and enzymes that had previously been treated as food — and gave the FDA authority to regulate it.

The industry quite clearly had a quality-control problem: Tests showed that supplements contained useless ingredients — rice, weeds — and unsavory substances such as heavy metals, carcinogens, glass, pesticides and pharmaceutical drugs. Many products promising weight loss, bodybuilding and sexual enhancement have been found to be anything but "all natural."

But as Congress established more oversight of the industry, it also made several key concessions. Whereas drugs must be shown to be safe before they're released, the FDA can't pull a dietary supplement off the shelves until it's proven unsafe.

Supplement companies don't have to substantiate the health claims on their labels before going to market, as long as they include a disclaimer and don't profess to address specific diseases. Claiming to be good for digestive health is OK; claiming to cure stomach cancer is not.

In 2007, the FDA issued rules for the manufacturing, packaging, labeling and storage of supplements. It established standards for production facilities, recordkeeping, handling complaints from consumers and testing the "identity, purity, strength and composition" of products.

In a press release at the time, Robert E. Brackett, director of FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, announced that the rules would "help ensure that dietary supplements are manufactured with controls that result in a consistent product free of contamination, with accurate labeling."

They took effect in 2008 for businesses with more than 500 employees, in 2009 for medium-size businesses and in 2010 for businesses with fewer than 20 employees.

The FDA's first visit to Urban Moonshine came in 2012 and seemed to go well. "She just made general suggestions, which made us feel really confident," King recalled of the inspector. The second, in 2013, wasn't as smooth. The inspector gave Urban Moonshine a 483 — industry parlance for the form filled out when a company violates FDA rules.

According to Masé, the biggest issue was with how Urban Moonshine was verifying the identity of its herbs. The company submitted a plan to come into compliance within the allotted 30-day period, and started making changes.

They heard nothing until November 2014, when the FDA put them on notice in a public warning letter that said Urban Moonshine's plan had been insufficient.

"It was a total shock," King said. "We realized how serious it was."

With just 15 days to submit a new plan, they sprang into action. The inventory-tracking system had to be tamper-proofed. Thousands of labels had to be tossed because they lacked FDA-required hairline borders around the text.

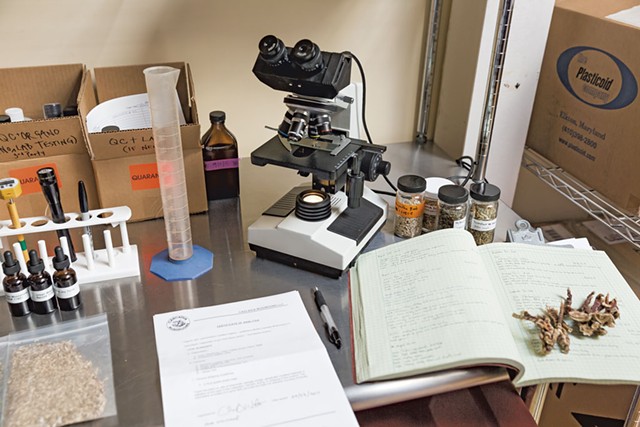

Masé brought a reporter into what now serves as the records room. In one file cabinet drawer, neatly labeled manila folders contained paperwork for Urban Moonshine's 40-odd herbs. Another drawer held files for its single-herb extracts such as lemon balm leaf and licorice root. A third contained thicker folders for the bitters, tonics and tinctures that contain multiple herbs. These papers are Urban Moonshine's proof that each batch contains the correct amounts of ingredients and has been steeped, agitated and pressed in a controlled setting, according to uniform standards. Two people must sign off every step of the way.

There were more hoops to jump through: To prove to the agency that Urban Moonshine herbalists could accurately identify raw herbs, Masé subjected them to a series of blind taste-tests — with a PhD present — to see if they could detect alterations. They passed.

"So now the FDA considers our herbalists equivalent to a chromatographic machine," Masé said, referring to the devices used to identify plants by their chemical components.

"Eighty thousand dollars later," King chimed in.

While Urban Moonshine's herbalists can ascertain the identity of herbs, they aren't capable of detecting whether bacteria or heavy metals have contaminated the plants. Big herb vendors test for this themselves. But Urban Moonshine still has to corroborate their test results — by sending the herbs to a lab three times — before the vendor tests are acceptable to the FDA. Herbs from small farms that don't test get sent to the lab every time.

In an effort to "test" itself, Urban Moonshine found an ex-FDA officer and paid him $9,000 to conduct a mock inspection. Among other feedback, the consultant told them something they already knew: They needed a bigger production facility.

Double Dose

Urban Moonshine was in the middle of retrofitting a large warehouse space two months ago when the FDA came calling again. This time King and Masé prepared — Masé had even begun drafting a manual to instruct other herbalists in how to comply with FDA rules.

According to King, the inspector took a bottle of Immune Zoom off the shelf and requested to see the master manufacturing record for that particular batch. Staff supplied him with roughly 200 pages.

To show him the company was capable of conducting a recall, King handed over phone numbers and addresses for every store that had received that batch of Immune Zoom.

The inspector repeated the process for six more products.

He also asked for the cleaning logs "to make sure floor was mopped when you tinctured the ginger," King recalled.

That was one of the 10 problems he flagged when he handed them another 483: On one day, an employee had neglected to record that the floors had been mopped. Another violation had to do with an employee sporting a nose ring. According to Masé, staff fixed eight of the problems before the inspector had even left.

But a fundamental problem remained: The FDA wasn't satisfied with how Urban Moonshine was confirming the identity, strength and composition of its multi-plant products before shipping them out to stores. It accepted that employees could accurately identify the raw echinacea, elderberries, elderflowers and ginger going into a batch of Immune Zoom. But after they added water, alcohol, honey, cayenne and cinnamon, and bottled the concoction, the FDA wanted proof that the final product contained the correct amounts of every ingredient.

Masé and King had thought it was enough that they had multiple "quality control checkpoints" throughout the manufacturing process — two people making sure that each batch is steeped, stirred, pressed and bottled according to strict specifications. Their argument: We know the herbs going in, we meticulously track them as they're converted to extracts, so there's no room for the finished bottle to be something it's not.

Part of the confusion, Masé explained, is that FDA rules don't specify how a company should go about proving the identity, strength and composition of its products, and inspectors won't give clear guidance. "The statute is very vague," Masé said. "Even the consultants are guessing."

He insists that there's no foolproof test to show the FDA what it wants. DNA tests are no good for testing liquids because most of the genetic material gets damaged by alcohol or pressed and strained out. Chemical analyses can also be unreliable for multi-plant blends, he continued, because there's significant overlap in plants' chemical components. "The problem is, a bioflavinoid from hawthorn berry may overlap with a bioflavinoid from elderberry," Masé said. "I have no way of telling you how much came from this plant or that plant."

An FDA spokesperson declined to comment on what she characterized as an open compliance case, except to say that Urban Moonshine's past violations could potentially make it subject to "seizure and injunction." King was told they were now at risk of being designated a "high risk" facility, subject to investigations every six months.

After the latest inspection, King made a difficult decision. Doubtful that she would ever be able to crack the bureaucratic code and appease the FDA, she chose to outsource production to a larger, certified organic manufacturer located out of state.

It was a heart-wrenching decision, she said, that necessitated laying off five workers, including two Libyan refugee women who've overseen bottling. King valued being able to preside over her elixirs from start to finish, and she was proud of the company's Vermont credentials.

She said she knows that telling the world about Urban Moonshine's FDA woes — and her decision to give up its made-in-Vermont cachet — could damage the brand. But it beats extinction.

"We're the canary in the coal mine," she suggested.

Squeezed Out

At the very least, King wants her bureaucratic odyssey to help small-scale herbalists prepare for similar challenges. She said the FDA's rules favor mass manufacturers over the small shops that are likely to care most about the quality of their products. "I don't want to say it, but we don't see that it is possible without really deep pockets to be compliant as a small manufacturer."

The bad apples are one thing. A study published last month in the New England Journal of Medicine found that "supplements" have been responsible for more than 20,000 emergency-room visits each year. But Urban Moonshine has never sent anyone to the hospital, nor has it been accused of selling an impure product, as far as King knows.

By cracking down on the whole category, "Sure, we're going to get safer supplements in plastic bottles in Walmart," King said, "but are you willing to sacrifice all of the traditional herbalists?"

Deb Soule of Avena Botanicals has run an apothecary in Rockport, Me., for 30 years. She was taken aback when told about Urban Moonshine's most recent FDA interaction. "That could happen to us," she said. She grows most of her own herbs; like Urban Moonshine's, they're all certified organic.

When Soule got a warning letter from the FDA last November, she took out a $300,000 loan to move her shop into a more professional manufacturing facility. She recently took out another $65,000 loan to hire a quality-control specialist. Soule is still trying to figure out how to meet FDA's requirements for testing multi-botanical blends.

Not every small herbalist is getting slapped with 483s. McGuffin, King and Soule all agree that there is significant discrepancy in how stringent the FDA is — depending on the region and the individual inspectors. McGuffin is optimistic that the FDA will consider changes to the current law. Based on conversations with officials, he said, "I don't think the FDA is close-minded about some rethinking of the actual words in the rule or how it's implemented."

One recommendation he plans to make: Enforcement should be more driven by concrete safety concerns, such as salmonella or glass shards. Nothing of that sort has turned up in the products of the "bona fide herbalists" he represents.

Soule wants more wholesale change: "I don't believe herbal tinctures belong in the category of dietary supplements," she said. King would also like to see a separate category for whole-plant herbal medicine. "We fully agree that the supplement industry is full of junk, but herbal medicine is different," she said.

Gladstar, who grew up on a 30-cow dairy farm in Sonoma County, Calif., sees a parallel between what happened to small-scale farmers starting in the 1950s and what's happening to companies like Avena and Urban Moonshine. When the U.S. implemented stricter farming regulations, big ag adapted, and small farms shut down. "We need to push back," the elder herbalist said. "Jovial can't do it alone."

The State of Vermont has no role in policing the industry.

The dietary supplement regulations also threaten small herb growers, such as Jeff and Melanie Carpenter of Zack Woods Herb Farm in Hyde Park. Because herbs are tested by the batch, it's cheaper to buy 300 pounds — rather than 20 — and that's often more than small farms can offer. King plans to keep buying local, even though it will cost her more.

"She can buy herbs from the mass market at roughly half the price she can buy from us," noted Melanie Carpenter, who is Gladstar's stepdaughter. To stay competitive, the Carpenters are forming a cooperative with a dozen other organic medicinal herb farmers who will pool resources and combine their herb lots in order to produce bigger batches.

Herbal Empire

Back in the tiny office she shares with several employees, King is preparing to pivot. She's hatching new plans for Urban Moonshine that include keeping the production space she'd already committed to rent.

Instead of housing barrels of steeping herbs, the warehouse will serve as a classroom, where Masé and other herbalists will instruct others in the art of making elderberry syrup. At a cooperatively owned clinic next door, herbal practitioners will see patients. Masé wants to rekindle the connection between medical schools and herbalists by establishing a relationship with the University of Vermont.

"We're really hoping to make Vermont a destination for herbal medicine," King said.

Jeff Carpenter predicts they will "educate the next generation of herbalists."

Urban Moonshine also plans to start a tonic bar where people can imbibe cocktails. Next door, as part of King's continued quest to lead people from aperitifs to other herbal remedies, the Railyard Apothecary — named for the still-active train tracks nearby — will offer more than 100 bulk herbs and tinctures, many supplied by local herbalists. When the owner of Purple Shutter Herbs passed away in March, the Burlington area lost its only retail apothecary.

A yoga studio and second classroom are also in the works.

Outside, they plan to convert the parking lots by the train tracks and gravel piles into gardens where people will learn to identify herbs. The plants won't be harvested, King explained, because the soil is contaminated. Stepping into the sunshine, Masé excitedly pointed out a scraggly mugwort stalk growing, improbably, in a break in the pavement. "It's an amazing digestive bitter," he explained. "It's also a dream-enhancing herb."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Bitters Dispute"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Business, Urban Moonshine, herbal supplements, herbal tinctures, health, wellness, Food and Drug Administration

More By This Author

About The Author

Alicia Freese

Bio:

Alicia Freese was a Seven Days staff writer from 2014 through 2018.

Alicia Freese was a Seven Days staff writer from 2014 through 2018.

Speaking of...

-

Herbal Tonics Business Urban Moonshine Returns to Vermont Ownership

Jan 17, 2024 -

'We Must Act Now': Burlington Council Passes Resolution on Drug Crisis, Public Safety

Oct 11, 2023 -

Q&A: Chet and Kate Parsons Talk About Their Final Lambing Season in Richford

Apr 12, 2023 -

Video: Last Lambing Season for Chet and Kate Parsons at the Parsons’ Farm in Richford

Apr 6, 2023 -

Garnet Health to Close, Citing Financial Difficulties

Jan 17, 2023 - More »

Comments (10)

Showing 1-10 of 10

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 2. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 3. Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State

- 4. Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate News

- 5. High School Snowboarder's Nonprofit Pitch Wins Her Free Tuition at UVM True 802

- 6. An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment

- 7. Vermont Senate Votes Down Ed Secretary Nominee Zoie Saunders Education

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis