Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

-

News

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont…

-

Housing Crisis

'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted…

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

- An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment 0

- Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

End of the Line? As Vermonters Cut the Cord, Rural Phone Customers Hear Static

Published July 19, 2017 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated August 1, 2017 at 8:58 p.m.

Morgan Wade gathered her tool bag, her bug spray and the spare phone she keeps in a clear plastic box and headed down to the end of her half-mile driveway in Canaan last month.

Standing in hip-high weeds, she unscrewed the cover of a gray box attached to a telephone pole, plugged her phone into a jack and dialed FairPoint Communications.

"I'm calling about the quality of the line," she told a customer service representative.

Calls like this have become a ritual for Wade. The phone line at the home she shares with her husband, Dan, and their 7-year-old son consistently carries an annoying buzz. When the noise gets so obtrusive that she can't carry on a conversation, Wade stands in the weeds — or the snow — near the end of the driveway to complain. By calling from there, she can demonstrate that the problem is the phone company's responsibility and not caused by the wiring she's responsible for between the road and the house.

The Wades' Buckwheat Hill Farm sits on nearly 250 acres in the farthest northeast corner of Vermont. The couple can see Canada from their kitchen window, and New Hampshire is just down the road. Until last November, the family had no access to high-speed internet. There is no cellphone service for miles.

The Wades understand that they live in the sticks, and they don't expect all the latest technology. But Morgan, a lawyer who works from home as a researcher for the database company LexisNexis, and Dan, who runs a maple sugaring operation, need their landline.

"We don't have the option to go to cellphones," Morgan Wade said.

She worries that she and neighbors who report similar troubles will be left behind — that someday it will no longer be economically feasible for the phone company to maintain their landlines.

"It's never been great," Wade said of her connection. But, she added, "What happens when it continues to get worse?"

The ongoing revolution in communications technology has given millions of people new choices for phone service but has also put new stresses on the financial stability of traditional telecommunications companies. They have been left with fewer customers, more competition and shrinking resources to maintain their existing networks.

In May, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, for the first time, a majority of Americans, 50.8 percent, only used cellphones. So many customers have cut the cord that at least 19 states have decided that telephone companies should be allowed to abandon landlines altogether, as long as other options exist.

Although Vermont is unlikely to endorse such a step anytime soon, Wade is not alone in worrying about the future of landlines for the diminishing number of people who rely on them.

"The notion that the bottom could fall out is very real," said Greg Marchildon, state director of AARP Vermont, which follows utility issues for its elderly members.

In Vermont, landlines are still a lifeline for some. Four years ago, the CDC found that, while 30 percent of Vermonters only use cellphones, a full one-third rely mostly or entirely on traditional telephone service. That's more than any other state except West Virginia.

"The absence of a landline could be life and death until we figure out a way to guarantee cell coverage," Marchildon said.

Phone service for people such as the Wades is also on the minds of state officials, said Clay Purvis, director of the Vermont Department of Public Service's Telecommunications and Connectivity Division.

"This is who I think about when I worry about the future," said the 34-year-old Purvis, who lives landline-free in Brookfield, but whose job involves ensuring reliability of legacy landlines. "The last mile is where you see degradation."

Cutting the cord

Losing the landline represents a cultural shift. Phone books are virtually useless; a generation is growing up unaware of the household phone; and the backdrop of everyday life now includes a cacophony of cellphone ringtones and vibrations.

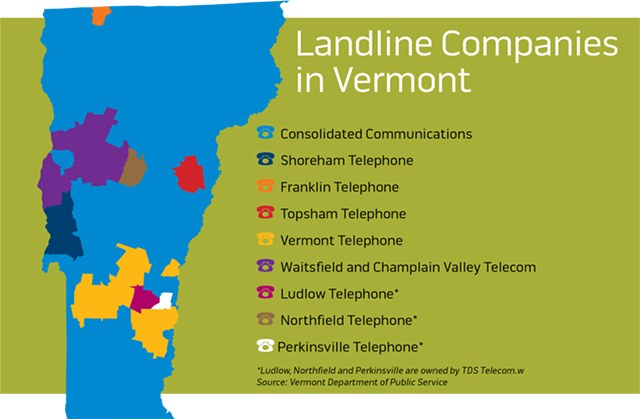

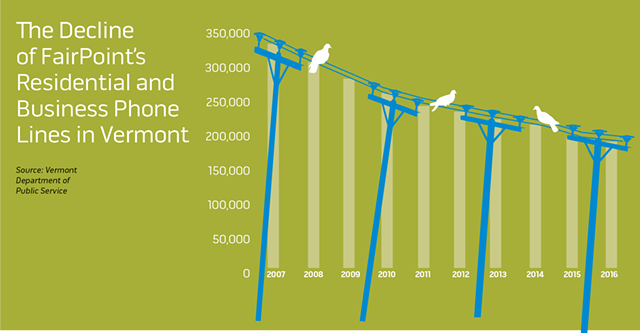

That shift has happened throughout Vermont, particularly in its most populated areas. FairPoint, which was acquired this month by Consolidated Communications, saw its landline numbers decline by nearly 60 percent in a decade, from 315,588 in 2005 to 134,521 in 2016. Smaller, more rural phone companies also saw decreases, though less dramatic, according to DPS data.

For some it has been simple to decide between cellphones and landlines. "I think it really was the idea of, what is this giving us that using just a cellphone doesn't?" said Naomi Roof, a Burlington resident who gave up her landline more than a decade ago. "We couldn't really think of anything. This was even pre-smartphones."

Roof lives in the Old North End of Burlington, where telecommunications options are bountiful. The city boasts dependable cell coverage. Three companies — Burlington Telecom, Comcast and Consolidated Communications — compete to offer phone, internet and television service.

"I have not missed it, especially because of the robocall piece," she said, noting that when her landline rang, a telemarketer was often on the other end. Friends and family typically called her mobile phone.

The 41-year-old mother of two has become so used to cell-only living that when she visited her sister in Williston recently, she was startled to hear the landline ring. Her first thought: It must be a telemarketer.

"It was actually for me," Roof said. "It didn't occur to me it would be a legitimate call."

While switching to cell-only service may eliminate an extraneous landline, it doesn't necessarily save much money. The math varies by household and depends on such variables as the quality of cell service or the cost of voice-over-internet options and whether every family member has a phone.

But those who get their phone and internet from one company may find that lopping off just the landline from the package doesn't save them the full price of phone service listed on their bills. That's because federal subsidies help pay for the landline portion of the cost. Providing only internet to customers still requires maintaining the same infrastructure, but with less federal help.

"Many times, it's very, very little savings," said Roger Nishi, vice president of industry relations at Waitsfield and Champlain Valley Telecom in the Mad River Valley, the largest of Vermont's eight small, independent phone companies. He argued that there are good reasons for customers to keep a landline even if they have decent cell service.

"If you were on a landline right now, it would probably be a clearer connection. You don't get cut off," he told a Seven Days reporter in a phone interview. "It's always there when you need it."

As if on cue, the reporter's cellphone dropped the call. Nishi, who was using a landline, didn't rub it in.

Vermont Center for Emerging Technologies president David Bradbury, who spends a lot of time thinking about the latest means of communication, is among those who wondered why his family bothered to keep their landline. He found a good reason the night of June 23. His 11-year-old son broke his leg in the backyard of their rural Stowe home. When it came to calling 911, cellphones lacked service, but the landline worked, Bradbury said.

"It's worth it," he said of his family's landline.

Bill Horne, a retired Verizon employee who lives in North Carolina and edits a blog called Telecom Digest, said there's little doubt that landlines are dying, but there is a risk to letting that happen.

Other options, he said, "are not nearly as reliable" during power outages and mass emergencies when many people are trying to make calls at once. Still, he conceded, he doesn't have a landline because he travels frequently and sees it as an unnecessary expense.

Many residential and business customers are reaching the same conclusion. A new Maple Street dormitory under construction at Burlington's Champlain College will have just a single landline in the common area for emergencies, according to spokesman Stephen Mease.

In 2009, the college had 952 landlines, including 422 in student dorm rooms. While the college has grown since then, its landlines have decreased to 818 and none in dorm rooms, Mease said.

To offset such declines, phone companies can't just raise their rates — both because they are regulated by the state and because they have competitors close on their heels. Other providers whose original focus was television or internet service are now offering phone service as well.

"There's a great deal of competition," said Mike Reed, Consolidated Communications' president for Vermont and Maine.

The chase for customers among those competitors is heated, Reed said. He seethed over a recent Comcast television commercial that characterized FairPoint as packing up and leaving town, when, in fact, Consolidated continues to provide service.

While traditional telephone companies such as his are regulated, the phone service from newer providers of internet-based telephone service, such as Comcast, is not. That means the state requires Consolidated to provide a minimum level of service to its entire coverage area, while competitors can choose to serve only the most profitable, populated territories.

That makes running traditional phone companies all the more challenging, said Nishi, who's worked for Waitsfield/Champlain Valley for 23 years. "We still need to maintain the whole network," he said. "Competitors will build where it's easier for them to serve."

State regulators require that they keep the landline links, but phone companies benefit from the fact that the same copper and fiber-optic lines that carry phone service also provide popular internet access.

"We've actually become a broadband company," Nishi said of his 113-year-old employer. "We encourage our customers to increase their speeds, and we try to get them the best service possible."

Internet to the Sugarhouse

click to enlarge

- Terri Hallenbeck

- Franklin Telephone manager Kim Gatesshowing off the company’s antique equipment

At the front desk of Franklin Telephone last week, receptionist Linda Hartman was on the phone with a customer. "If you don't want the DSL in the sugarhouse now, we can just turn it off," she told the customer. "Or you can just pay for it all year."

As she talked, Hartman was surrounded by equipment from a bygone era. On one corner of her desk sat an old crank-style wooden phone. Behind her was a potbelly stove, which is still used to heat the cramped Main Street storefront in winter.

The state's smallest telephone company lives with a foot in two eras. Customers are looking for high-speed internet in their homes, barns and sugarhouses, but many still come to town to pay their bills in person.

"Things have changed a lot," said Kim Gates, whose great-grandfather founded the utility in 1894 so that his farm store could communicate with the railroad five miles away.

She is one of four employees — three of them family members — still running the company. It serves 800 customers in the rural northwestern Vermont towns of Franklin, Highgate and Sheldon. A quarter of those customers are seasonal camp owners at Lake Carmi.

The company has responded to change the same way larger phone providers have — by expanding its business beyond landlines, Gates said.

"We've invested a lot in the latest technology," she said. "We can offer all of our customers high-speed internet. It's a continual process." But, she added, providing television service proved cost-prohibitive.

Just as movie theaters survived the onset of VHS tapes and DVDs, Gates noted, phone companies are surviving changes in the way customers connect. "People always need a way to communicate, whether it's telephone or internet," she said.

Still, Gates' company lost about 100 phone lines between 2005 and 2016, according to DPS data. And more competition keeps coming. Comcast now offers not just television but internet-based phone service to part of Franklin's coverage area. A third company, wireless internet provider GlobalNet, has also moved in, she said.

Cell coverage is "limited" even in downtown Franklin, Gates said, but some customers are attaching equipment to their internet routers to provide cell service at home. That means they're no longer using their landlines for long-distance calls, she noted.

Gates acknowledged that providing service on every rural road will grow more challenging if the number of customers and federal funding for maintaining those lines continues to decrease. "How much money do you continue to put into funding everybody?" she asked.

Nishi has the same questions at Waitsfield/Champlain Valley. The Mad River Valley company started in 1904 when telephone service was still in its infancy.

Nishi's employer saw a decrease in the number of residential and business phone lines from 20,824 in 2005 to 16,016 in 2016, according to the DPS. That followed a high point in 2002, when fax machines were still in vogue and dial-up internet service was driving people to add phone lines to their homes and businesses.

"We're feeling the pressure of losing long-distance revenue and losing local lines," as well as the loss of federal subsidies for landlines, Nishi said. Nevertheless, he said, "People expect us to maintain the lines."

The Universal Service Fund, overseen by the Federal Communications Commission, has long offered phone companies incentives to serve rural areas, but this year Vermont's eight independent phone companies will see an 18 percent decrease in USF money, Nishi said.

That means companies will have less money to upgrade internet speeds and maintain traditional phone lines. "It's concerning," he said.

Purvis, at the DPS, put the telephone companies' plight this way: "I don't foresee that they're going to be left to die, but the economics for them is getting to be more of a challenge every year."

Consolidating FairPoint

At Consolidated Communications' offices on Main Street in Burlington, a portion of the second floor used to house a team of operators who answered directory assistance calls. The company now donates that space and one gigabyte of broadband to Bradbury's Vermont Center for Emerging Technologies, a nonprofit organization that helps startup companies.

The company's loss of local lines over the last decade is proportionally greater than smaller outfits, such as Waitsfield/Champlain Valley, in large part because its territory includes more populated areas of Vermont, where other companies are eager to compete, Purvis said.

In Maine, Consolidated has been working to level the playing field with such competitors. State regulators granted the company's request for relief from regulation in some of the most populous municipalities. The move is increasingly common across the country in areas with plenty of competition — a recognition that phone companies no longer have monopolies there.

Deregulation frees a telephone company from the obligation to provide phone connections in those areas. Reed said, however, the goal is not to drop existing service but to eliminate requirements that the company document its service record to the state, which its competitors don't have to do. "When competition takes over, regulation has to back off," Reed said.

The move could also give the company more flexibility in the rates it charges, which could lead to higher costs for consumers as the market allows.

Consolidated might at some future point request such deregulation in populated areas of Vermont, Reed said. But Purvis said the state would be wary of leaving some customers without landline phone service. "I don't foresee it anytime soon," he said.

In other states, telephone providers have sought permission to get rid of copper-wired landlines entirely in favor of wireless networks or fiber-optic lines. AT&T won such approval from the Illinois legislature this month. The FCC must also approve the move before the phone company can proceed.

The FCC is considering a change in rules to make it easier to retire copper phone lines, but spokesman Mark Wigfield said the agency wants to avoid leaving customers without other options. Such decisions, he said, will be made on a case-by-case basis.

Meanwhile, Consolidated has promised to invest in Vermont. In order to win approval from state regulators for its acquisition of FairPoint, Consolidated agreed to plow 14 percent of its Vermont revenues over the first three years into its overall state operations and another $1 million a year for three years into specifically targeted "areas with ongoing service quality concerns."

Purvis said that investment will likely amount to at least $17 million and will bolster service for those most dependent on landlines. "The purpose of the $1 million is to take care of situations like Morgan's in Canaan," he said.

While there's no hard evidence to indicate that landline service in Vermont is at a physical breaking point, customers are sometimes left hanging. In 2016 and the first quarter of 2017, FairPoint fell short of its required level for service complaints cleared within 24 hours. But the 61% performance rate was an improvement over the 43% the company reported in 2015.

Gates, at Franklin Telephone, said water damage is a common source of problems with copper lines that drive customers to complain. "Over time, you'll get lightning strikes and water damage, and the copper corrodes and the connection fails," she said. "If you're lucky, it just corrodes in one spot."

Replacing copper is expensive, she said. Fiber-optic cable is actually cheaper by the foot but more expensive when adding in the electronics needed to connect the line to a house, she said. Maintaining more modern fiber-optic lines also presents challenges, but they don't attract lightning, Gates said.

Is there Life for the Line?

For the time being, phone companies are keeping the network running, but those who follow telecommunications in Vermont say something more will have to be done to protect those at the end of the line.

Nishi, at Waitsfield/Champlain Valley, said he believes either the federal government will have to direct more subsidies for the hardest to serve, or prices will have to increase.

"Those that are easy to serve now have choice. Those at the end of the line don't have choice. Those are the customers that will either need funding, or rates will have to rise," he said.

Tom Evslin of Stowe, a former telecommunications consultant, said the FCC should be making a game plan to ensure that coverage continues in the most rural areas. He argues that it doesn't have to be via traditional landlines.

"You need a two- to three-year plan. Where are we going to extend broadband, and how does that cut down on the number [of customers at risk]?" he said, as a robust internet connection offers customers the option of voice-over-internet phone service.

Once the number of landline-dependent customers is down to a relative few, he said, "Buy them satellite phones. Compared to the cost of subsidizing service for a few people, it's not expensive. There's nobody that we can't provide service for. It's just a question of how much it's going to cost."

Bradbury agreed. "Is it important that a landline go to every location, or do we just have to have connectivity?" he asked. "It may not make sense to run a lot of physical infrastructure."

In Canaan, meanwhile, town officials have been working on bringing cell coverage to at least some portions of the town. Wade does not anticipate that dependable coverage is on the horizon. She is more focused on ensuring that her landline works.

Two days after she called FairPoint's customer service from the end of her driveway, a technician visited on a Sunday morning.

"He found an area down the road where moisture was getting in and affecting our junction," she said. Service improved noticeably, she said.

But if past experience is any indication, the buzz will return and she will be back at the end of the driveway, calling the phone company and wondering if the day will come when there will be no one at the other end of the line.

The original print version of this article was headlined "End of the Line?"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Tech, FairPoint Communications, Vermont Department of Public Service's Telecommunications and Connectivity Division, Franklin Telephone, Consolidated Communications, Waitsfield and Champlain Valley Telecom, Vermont Center for Emerging Technologies

More By This Author

About The Author

Terri Hallenbeck

Bio:

Terri Hallenbeck was a Seven Days staff writer covering politics, the Legislature and state issues from 2014 to 2017.

Terri Hallenbeck was a Seven Days staff writer covering politics, the Legislature and state issues from 2014 to 2017.

Speaking of...

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 2. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 3. Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State

- 4. Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate News

- 5. Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down in December News

- 6. High School Snowboarder's Nonprofit Pitch Wins Her Free Tuition at UVM True 802

- 7. An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis