Published November 16, 2011 at 11:20 a.m.

Paula Jean Welden wasn’t known as the type of person who took off without telling her friends or family where she was going. Until one Sunday in 1946.

After working the lunch shift in the school’s dining hall, the 18-year-old art major at Bennington College left campus at about 2:30 p.m. on December 1. A passing motorist picked her up hitchhiking 15 minutes later and dropped her along Route 9, a few miles from Glastonbury Mountain.

Welden — who was slim and fit, with blue eyes and wavy blond hair, according to a subsequent police description — told the driver she planned to hike the Long Trail. An experienced camper from Stamford, Conn., Welden was last seen at 4 p.m. by a fellow hiker, whom she asked how far the trail went. All the way to Canada, he told her. Several hours later, it began to snow.

When Welden didn’t show up for classes on Monday morning, college officials called police, whom began seeking leads. Friends told them that, despite her good looks, Welden never had a steady boyfriend. Family members said she was occasionally depressed, but was never down enough to take her own life.

Police from Vermont, Connecticut and New York scoured the Long Trail and surrounding areas for weeks but turned up nothing. Did Welden freeze to death? Was she kidnapped? Was she murdered and buried along the trail? No one knows, as her body was never recovered.

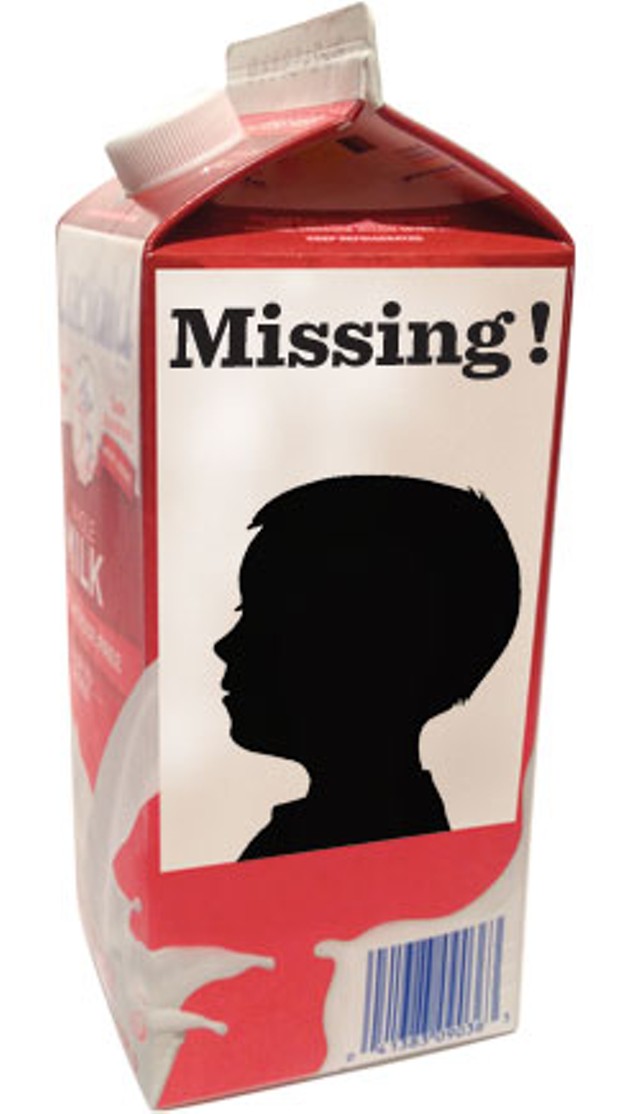

Thousands of Vermonters have gone missing in the last century. The cases range from rapidly resolved disappearances to enduring mysteries to current puzzlers, such as that of William and Lorraine Currier, the Essex couple who disappeared on June 8.

But Welden’s case stands out for one reason: Her disappearance revealed that local police at the time were woefully ill equipped to handle such investigations on their own. Thanks in large part to the lobbying of Welden’s father, in 1947 the Vermont Legislature created the Department of Public Safety and its law-enforcement arm, the Vermont State Police. Today, the VSP serves as the central clearinghouse for all missing-persons cases in the state, lending its expertise, staffing and other resources to what are often time-consuming and highly technical investigations.

However, the VSP rarely takes the lead on missing-persons cases; that’s the job of police in the locality where the person disappeared. As a result, such investigations can vary with the agencies working them. While Vermont’s approach to missing-persons cases has evolved considerably since Welden’s day — and continues to do so — not all of those agencies avail themselves of the high-tech resources now available.

Nationwide, missing-persons investigation has advanced light-years since Paula Welden’s disappearance. Today, many critical details about her — the small scar under her left eyebrow, the red parka with fur-trimmed hood she was wearing when last seen, her Elgin wristwatch with repairer’s markings scratched inside the case — could all be entered in a national database known as the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs for short.

The NamUs, which was created in 2007 and is maintained by the National Institute of Justice, is designed to match the DNA of missing persons to the tens of thousands of unidentified human remains found nationwide. In June 2007, the Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that, in a typical year, coroners and medical examiners handle about 4400 unidentified remains, of which 1000 are still not identified after one year.

The NamUs website, which is free and accessible to the public, currently lists 16 missing Vermonters. The newest additions to the list are William and Lorraine Currier. The oldest case: Lynne Schulze, an 18-year-old Middlebury College student who went missing on December 10, 1971.

Yet the Curriers are not the most recent Vermonters to be reported missing — nor does the NamUs’ total of 16 match that held by the state police. As of last week, the police listed 43 persons missing in Vermont: 28 adults and 15 juveniles, including 17-year-old Marble Arvidson, who disappeared from Brattleboro on August 27, shortly before Tropical Storm Irene hit (see sidebar).

Why the discrepancy? Shouldn’t all unaccounted-for Vermonters, including Arvidson, be listed in the four-year-old federal database? They aren’t, for various reasons — some stemming from the facts of the case, others from the investigators’ approach.

Things could be worse. Lt. Mark Lauer recalls that, in 2007, the Vermont State Police website listed the names of 76 missing persons. More than 30 of them had already been found.

Lauer updated and overhauled that website when he took command of the Vermont Fusion Center (VFC) in Williston, one of 72 such centers around the country that were created after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Each fusion center has its own mission, depending on its location. Some focus on homeland-security threats, others on illegal immigration. Generally speaking, their overarching goal is to help state and federal law-enforcement agencies share information in a timely manner and to prevent the accumulation of their findings in inaccessible “silos.”

The VFC, which is staffed by state police, focuses primarily on crime solving and unsolved disappearances. Lauer, its commander since 2007, has been the “go-to person” at the VSP for all missing-persons cases for about a decade. He also activates Vermont’s Amber Alert, the nationwide emergency broadcast system used to help recover missing and abducted children believed to be in imminent danger.

“When I first came to the fusion center, it occurred to me that we, as an agency, didn’t have a very good handle on missing persons,” Lauer says. One example was the state police website, with its lack of “clean” information, which reflected little follow-up, management or coordination with local police.

To address the problem, Lauer and his staff built a database of all outstanding missing-persons cases and adopted better policies for future reports. Today, when someone goes missing in Vermont, Lauer’s staff immediately contacts the lead agency to offer assistance. That includes producing a flyer with identifying information, such as the person’s name, age and physical characteristics, as well as any available photos and lead-agency contact info. The case is then time and date stamped, and the clock starts ticking.

Contrary to popular belief, a person need not be missing for 24 hours before police will consider an investigation, Lauer notes. In fact, because the first 48 hours are critical in solving abduction cases, the authorities want to know as soon as possible.

What transpires next depends on the circumstances, Lauer explains. An Alzheimer’s patient who wanders off from a nursing home in the dead of winter will elicit a very different response from, say, a 16-year-old boy who disappears after a fight with his parents over his curfew. In both cases, however, police are required by law to enter the name of the missing in the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database within two hours.

Yet the New York Times reported last year that police often don’t comply with that mandate. One such oversight, the Times found, involved a 13-year-old boy with Asperger’s syndrome who ran away from home and spent 11 days riding the subways in New York City. NCIC reporting is critical, police say, because it’s the only way they will know when they encounter someone who is wanted or presumed missing.

Once the VFC receives a missing-persons report, Lauer’s staff initiates preliminary legwork of its own, including open-source searches using Google, Facebook, MySpace and Twitter.

“Sometimes someone will post something on their Facebook page and say, ‘Hey, going to Colorado for the weekend,’” Lauer reports. “Now they’re not missing anymore.”

Occasionally, Lauer’s staff offers more technical assistance, such as accessing the individual’s financial statements and cellphone records (with a subpoena) or enlisting the help of out-of-state law enforcement. For example, Lauer was recently involved in an abduction case involving a father who disappeared with his wife and children shortly after committing a crime. (Because the investigation is ongoing, Lauer can’t reveal specifics.)

The investigating detective suspected the father had fled to one of four other states but wasn’t sure which one. With assistance from the VFC, local police were able to search the data of automated license-plate readers in all four states — and got a hit on the father’s car, significantly narrowing their search.

Once a person has been missing for seven days, Lauer strongly encourages local police to enter the individual’s data in the NamUs and begin gathering DNA samples, dental records and other identifying info from family and friends. These measures are taken even when police don’t suspect foul play, he says, because they preserve that material should it be needed later.

However, Lauer admits that local police are free to handle each case as they deem appropriate. While entry in the NCIC database is required, there’s no legal mandate that Vermont police use the NamUs database at all.

“We can’t make them do anything, but we can certainly push them,” Lauer says. “Our cooperation between agencies is much, much better than I’ve ever seen it in my career ... but it’s not perfect.”

Why wouldn’t local police use all the resources at their disposal? Sometimes, Lauer explains, their reluctance is due to the seemingly less pressing nature of the case — such as that of a teen who’s run away from home repeatedly. Or the local agency may be small and have limited resources to devote to the investigation. Or, Lauer acknowledges, some cops may find the NamUs daunting because it asks for a large volume of information.

What happens when the trail leads nowhere? Another popular public misconception, Lauer says, is that police eventually list a missing person as a “cold” case.

“We don’t officially use that term,” he says, “but, yes, there is a point when you’ve exhausted all your leads.” For example, in the early months of the Currier case, both the Essex PD and the state police had as many as 10 detectives working on it around the clock, seven days a week. Lauer’s staff even set up a “war room” in their Williston headquarters where all the relevant info was displayed on bulletin boards.

Today, the VFC still assists Essex on that disappearance, but “that’s all calmed down,” Lauer says. “We just can’t expend those kind of energies.”

In short, he says, once the leads are exhausted, police are often forced to move on to fresher cases. Sometimes, Lauer acknowledges, people simply “walk away from life, and there’s no crime in that.”

While Vermonters may be missing for weeks, months or years, they’re never forgotten. One crucial policy was put in place after the disappearance of 17-year-old Brianna Maitland of Montgomery in March 2004: Every missing person in Vermont is now assigned a state trooper who serves as the liaison with family members to keep them apprised of any developments.

Captain Glenn Hall has maintained regular contact with the Maitland family. Hall readily admits the Maitlands were initially very unhappy with the way police handled Brianna’s disappearance. (The Maitland family didn’t respond to requests from Seven Days, via the state police, to be interviewed for this story.)

“We don’t get a lot of these cases,” Hall says. “It’s pretty rare that a 17-year-old girl just vanishes and seven years later there’s no sign of her, and we can’t figure out what happened.”

But, Hall notes, the Maitland case changed the way missing-persons reports are handled in Vermont, in large part because the family kept pushing police to do more. Regular contact with families of the missing is now not a recommendation but a requirement.

Seven years later, Hall still investigates fresh leads and occasionally looks into old reports. And, at a bare minimum, he checks in with the family on the anniversary of Maitland’s disappearance. Despite the time that’s passed, he says, “We’re never going to stop working this case.”

For more on missing persons in Vermont, click here to read "Inside a Case", a story about the Marble Arvidson case by Megan James.

Snapshots of Vermont's Missing

Sixteen people are listed in the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), dating back to 1971. Here are a few of the cases that still confound police.

Lynne K. Schulze

Missing since: December 10, 1971

Missing from: Middlebury College

Age at time of disappearance: 18

Height: 5’3”

Weight: 115 pounds

Hair: Light brown

Eyes: Blue

Clothing: Maroon sweater, jeans, brown parka

Circumstances: Schulze was walking with friends to a final exam when she returned to her dorm to grab a favorite pen. She never showed up at the exam, and her wallet, checkbook and belongings were found in her dorm room. Rumors that she had been seen hitchhiking along Route 7 on the day of her disappearance were never confirmed.

Brianna Maitland

Missing since: March 19, 2004

Missing from: Montgomery

Age at time of disappearance: 17

Height: 5’4”

Weight: 105 pounds

Hair: Brown

Eyes: Hazel

Circumstances: Maitland’s coworkers at the Black Lantern Café watched her drive away at about 11:30 on the night she disappeared. Her Oldsmobile was found three days later backed into an abandoned farmhouse one mile from the café. Uncashed paychecks, keys and medicine were still in the car. Two years after her disappearance, a caller to the Vermont State Police claimed he’d spotted Maitland in an Atlantic City casino. Based on videotape evidence, her parents believe this person could be Maitland, but her whereabouts remain unknown. Police suspect foul play.

Selinda (“Cindy”) Jean Winegar

Missing since: March 21, 1979

Missing from: Burlington

Age at time of disappearance: 16

Height: 5’4”

Weight: 115-120 pounds

Hair: Blond

Eyes: Blue

Clothing: White-and-green striped shirt, jeans, sneakers, numerous rings

Circumstances: Winegar was last seen as she left her family’s home on Forest Street in the New North End. A few days after she vanished, her mother received a phone call from an anonymous party saying Winegar had been murdered and her body was at the bottom of the Winooski River. The river was never dredged, but a friend of Winegar’s sister claimed she snagged a clump of blond hair while fishing on the river in 1985.

Audrey Groat

Missing since: August 21, 1993

Missing from: Montpelier

Age at time of disappearance: 41

Height: 5’6”

Weight: 120 pounds

Hair: Blond (dyed)

Eyes: Blue

Circumstances: Groat spent her last known evening shopping and drinking beer with her boyfriend, who dropped her off at a park-and-ride commuter lot at around 10 p.m. Her pickup truck was later found at the lot with the keys locked inside. Her boyfriend — who subsequently admitted to sexual assault on one of Groat’s six daughters — was initially a prime suspect, but he is no longer the focus of the investigation. The police have searched the area near the park-and-ride and still consider her disappearance suspicious, though Groat has been declared legally dead.

Perry Grant Matheson

Missing since: September 30, 1993

Missing from: Barre

Age at time of disappearance: 51

Height: 5’11”

Weight: 185 pounds

Hair: Brown

Eyes: Blue

Circumstances: Matheson was living with his brother, George, when he drove away one morning in his 1989 Toyota Corolla and did not return. George Matheson said his brother was upset over their mother’s illness. Perry Matheson’s burned-out car was later found in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, along the Kancamagus Highway.

Brooke S. Avery

Missing since: March 19, 2011

Missing from: Barre

Age at time of disappearance: 16

Height: 5’3”

Weight: 100 pounds

Hair: Brown with blond highlights

Eyes: Brown, wears glasses

Clothing: Carhartt jacket, jeans, white shoes

Circumstances: Avery had been living in Vermont for a week when she vanished on her way to dinner with a friend’s family in Barre. She had not been on good terms with her parents, who lived in Michigan, and moved back to Vermont to be near an older half-sister. She reportedly left a note with her sister and was carrying a duffel bag when she disappeared.

Grace and Gracie Reapp (mother and daughter)

Missing since: June 6, 1978

Missing from: Jericho

Mother’s age at time of disappearance: 32

Height: 5’7”

Weight: 190 pounds

Hair: Brown

Eyes: Brown

Circumstances: On June 6, 1978, Grace Reapp reportedly left a note stating that she and her 5-year-old daughter, Gracie, had left their home for good. She left behind two sons, ages 7 and 11. Ten days after her disappearance, her husband, Michael, filed for divorce; he later married the couple’s babysitter. The police reopened the Reapps’ missing-persons cases in 1987 and reclassified them as homicides in 1995. Michael Reapp disappeared in 1997 and was identified 13 years later as a “John Doe” who shot himself in the head after a police chase in California the year he vanished. Twenty-five searches of the Reapps’ 10-acre former Jericho home have been conducted since 1978, and authorities believe Grace and Gracie’s remains could still be on the property.

More By This Author

Speaking of Justice, local Issues

-

Best rock artist or group

Aug 1, 2018 -

Opinion: Should Rape Victims Get Custody Rights?

Feb 26, 2014 -

At the Junction of State and Federal Law, I-91 Checkpoint Becomes Site of Legal Collision

Feb 5, 2014 -

Maple Makeover? Vermonters Discover a New Sugaring Technique

Feb 5, 2014 -

Disharmony on Prospect Street: A Dispute Between Neighbors Strikes a Sour Note

Feb 5, 2014 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.