Published September 17, 2014 at 10:00 a.m.

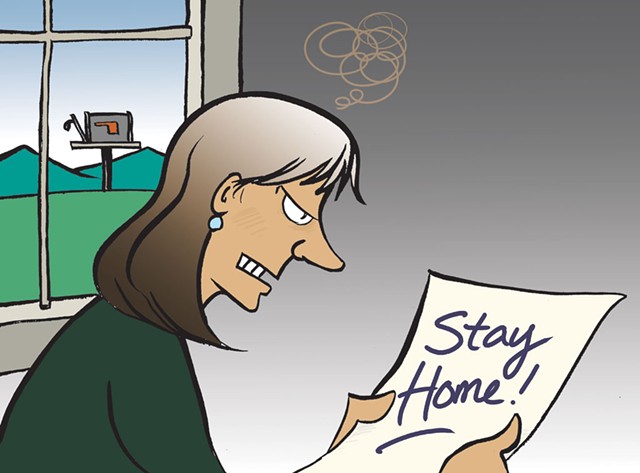

Two days after announcing her run for a Vermont Senate seat in Windsor County, Becca Balint received a handwritten postcard in the mail that read, "I urge you to end your political ambitions and stay home with your children."

It was a black-and-white reminder that, even in progressive Vermont, female candidates sometimes face an uphill battle. Balint has no idea who sent the note, though she spent some time wondering. Was this a neighbor who was judging her choices? A stranger she'd never met?

A newcomer to politics, the mother of two found herself weighing her own doubts, too.

"We all have these inner saboteurs who tell us we shouldn't do things," said Balint. For women with children, she said, that saboteur sometimes asks, Are you making the right choice for your family and your spouse?

"It's not that men don't weigh that as well," said Balint. "I think they do." But in speaking with other politicians, male and female, she's come to believe that it's "a much stronger barrier for women."

That is one of several theories to explain Vermont's relative shortage of women politicians. When Vermont voters head to the polls in November, they'll see only one prominent female candidate for statewide office on the ballot: incumbent state treasurer Beth Pearce. She's running for reelection — for the second time — but Governor Peter Shumlin appointed her to the job. She took former treasurer Jeb Spaulding's place when he left to become Shumlin's secretary of administration.

The scarcity of female candidates, particularly for higher office, points to a paradox in Vermont politics. On one hand, the state consistently ranks at or near the top of all states when it comes to female representation in the Statehouse. Currently, 40 percent of state lawmakers are women, a figure bested only by Colorado's 41 percent.

On the other hand, Vermont is one of only four states that has never sent a woman to the U.S. House or Senate. Contrast that with its conservative neighbor, New Hampshire. Two years ago, the Granite State became the first in the country to send an all-female delegation to D.C.

Several of Vermont's largest cities — including Burlington, Rutland and Barre — have never had a female mayor. This year marks 30 years since the state elected its first female governor, Madeleine Kunin, and since then no other women have followed in her footsteps.

What gives?

Balint's isn't the only theory. First and foremost, as a small state, Vermont has a limited number of positions of power, and voters tend to reelect people in office.

"Incumbency is extremely strong in Vermont," said Dawn Ellis, a Democratic candidate for Senate in Chittenden County. She posits that it might be time for Vermont voters to weigh the benefits of incumbency — namely, wisdom and experience — against the need for "a fresh perspective."

"I'm imagining that we'd do well if we have a mix of both," said Ellis.

Getting that fresh perspective is the focus, in part, of a new group recruiting Democratic women to run for office. Both Ellis and Balint participated in Emerge Vermont, a local chapter of a national organization devoted to training female candidates. The chapter grew out of a conversation among women in politics in the Statehouse in 2013; Balint and Ellis are two of four current candidates from the inaugural class who've elected to run for office.

Director Sarah McCall theorizes that the reason women make it to the Statehouse, but rarely venture beyond, is both the blessing and curse of Vermont politics: In Vermont, McCall says, "You really haven't seen a sophistication of campaigns that you would see in bigger states." Meaning candidates, male and female, can land in the Statehouse without mounting major fundraising efforts or outreach campaigns. In small towns, knowing your neighbors and knocking on doors can get you elected.

"That's not the case when you decide to run for statewide or federal office," says McCall. "You have to raise money and get your message to voters around the state."

Political savvy isn't the only thing holding women back from higher offices. Self-doubt might play a role, too. McCall says studies have shown that women need to be asked, on average, six times before they agree to run for office.

Those are conversations that Emma Mulvaney-Stanak, the chair of the state's Progressive Party, has had countless times with would-be candidates.

"Often the women I'm talking to are highly confident, and highly educated," said Mulvaney-Stanak — which makes it all the more surprising when most tell her, "I don't think I'm ready or qualified yet."

"Men don't usually have those conversations," said Mulvaney-Stanak, who has been recruiting candidates for the last five years. "They aren't the ones who say, 'Hmm, I need to do more homework on this issue.'"

Rep. Sarah Buxton, (D-Tunbridge), points to her own story by way of example. After graduating from Vermont Law School, Buxton recalls, she sat down with her friend and mentor, the late Cheryl Hanna, to brainstorm what might come next. Buxton had gotten her start in the political world as an undergraduate at the University of Vermont, interning with then-governor Howard Dean. She worked for Dean after graduating, spent several years in D.C. at the Children's Defense Fund and worked on Dean's presidential campaign before running a successful congressional race for a candidate in Toledo, Ohio.

Even so, she didn't initially consider herself qualified to run for the state legislature. When she confessed that to Hanna, she recalls, "She laughed at me, and she said, 'Sarah, you've been directing national campaigns, and you think you can't run for the state legislature?'"

Buxton did run — and Hanna's was the first campaign contribution she accepted. Buxton beat out her incumbent opponent by just one vote.

"My own experience tells me this, and studies support it: Women are not conditioned to show the same degree of political ambition [as men]," says Buxton.

Burlington City Councilor Rachel Siegel had a similar reaction when she was recruited by the Progressive party to run for office. "My immediate thought was, 'I'm not qualified for that.' Not, 'Do I want to? Does that work for my family?'" she said. "It was just, 'I can't.'"

Siegel ran into other complications once she overcame what she called her "internalized sexism." On the campaign trail, she found herself fielding questions about how she'd balance work and family in a way that male candidates didn't seem to get.

What's the solution?

"In my view, in the ladder to leadership, supporting diversity means that those in power have to actively make way for a different outcome," said Buxton. That means, among other things, recruiting, endorsing and supporting women to appointments on boards and commissions. "All of our leaders right now will say, 'Yes, we support women. Yes, we love to see them in positions of power.' It's still not enough."

And that might mean circumventing the traditional coming-up-through-the-ranks pick.

"The fear that I hear from them is, 'Look, there just aren't enough positions,'" said Balint. "It is difficult for women to break into that, because there is this unspoken order. There is this assumption of who is next in line."

The effect can be cyclical.

"When little girls don't see themselves represented ... it sends a message that, 'Maybe that's something that I'm not qualified to do,'" said Mulvaney-Stanak. "We have to do a better job of putting women up front, because younger people look to that."

In the three decades since her 1984 election to governor, Kunin has noticed progress in Vermont. She points to larger numbers of women in the legislature, as well as legislative leadership positions. For a time, women chaired all four of the "money" committees in the Statehouse, heading up Appropriations and Ways and Means in both the House and Senate.

"There are many more role models around," said Kunin. And she thinks Vermonters, by and large, no longer balk at female candidates. (The letter-writer who chastised Balint might be the exception to the rule.)

"It's no longer, 'Here's a woman,'" said Kunin. "It's, 'Here's a legislator.'"

Even so, Kunin said that 30 years ago, she had higher hopes for the state. She expected more women to follow in her own footsteps as governor, and assumed that more women from Vermont and beyond would be serving in Congress, where female representation currently stands at just 18.5 percent.

Said Kunin, "I didn't fully appreciate how long and slow a process this has been."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Girl Power: Why Doesn't Vermont Elect More Women to Higher Office?"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Crumbs: New To-Go Cocktails; Celebrating Women in Beer

Mar 1, 2022 -

Video: The Future Is Bright for Murray Electric

Dec 16, 2021 -

Video: South Burlington Bus Driver Steve Rexford Is Part of the Team

Oct 7, 2021 -

Book Review: 'The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women,' Nancy Marie Brown

Sep 22, 2021 -

After Failed Merger Votes, Essex Junction Plans to Break From the Town of Essex

Apr 28, 2021 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.