Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

-

News

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont…

-

Housing Crisis

'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted…

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

- An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment 0

- Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

'Beau Is Afraid' in a Fascinatingly Paranoid Vision From Ari Aster

Published May 17, 2023 at 10:00 a.m.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of A24 Films

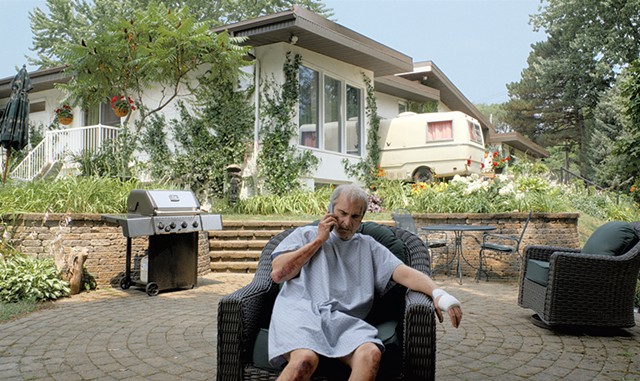

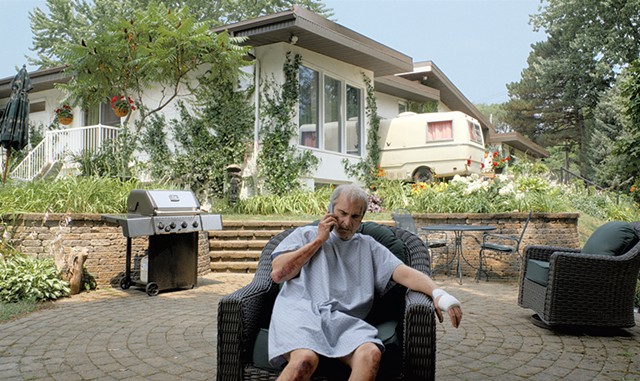

- Phoenix plays a perpetual victim in Aster's nightmare comedy about the inner workings of anxiety.

I'm sorry, Mom. This Mother's Day, instead of fêting you with brunch and gifts, I watched a three-hour movie about a man who has major issues with his mother.

Writer-director Ari Aster turns from arty horror movies (Hereditary, Midsommar) to just plain art movies with the surreal family comedy-drama-nightmare Beau Is Afraid. In limited release, the movie inspired walkouts and outraged Twitter disquisitions on self-indulgence, all of which only made me want to see it more. As of press time, it's screening at Merrill's Roxy Cinemas in Burlington.

The deal

Beau Wassermann (Joaquin Phoenix) is indeed afraid. Of everything. With reason. In the opening scene, his therapist gives him a new prescription to treat his anxiety. Within the 48 hours that follow, Beau will be repeatedly accosted in the street, harassed by an unseen neighbor who makes bizarre accusations in scribbled notes, burgled, locked out of his apartment building, home invaded, shot at, stabbed by a naked serial killer and hit by a car.

And that's just the start of his troubles. As Beau struggles against a hostile world to fulfill a promise to visit his mother, Mona (Patti LuPone), on the anniversary of his father's death, he receives news that puts him on a new and even stranger path.

Will you like it?

Mammoth movies in which acclaimed filmmakers test the audience's patience by plumbing the depths of their own neuroses are a genre unto themselves. (See the sidebar for two more examples.) I have a greater tolerance for this kind of navel-gazing than most; for me, the test of these films is whether the director manages to make his personal woes (yes, it's almost always a "he") relevant to anyone else.

For this viewer, Beau Is Afraid passes that test. Beau's travails are instantly recognizable to anyone who's ever suffered from anxiety — not as actual experiences, mind you, but as a lurid parade of possibilities. While the first scene is mistakable for our reality, Beau soon steps outside into a neighborhood that is a landscape of personified fears: Every unhoused person is aggressive; every cop is trigger-happy; every kid is shrieking; every shop has a vulgar name like Cheapo Depot or Erectus Ejectus. Only Beau seems capable of empathy and averse to violence, and he walks with stiff-legged terror, an urban zombie.

It's easy to be reminded of the comic book-inspired world of Joker, in which Phoenix similarly played an object of relentless persecution. But there's a key difference: Aster pushes things so far that it's impossible for us to see Beau's narrative as reliable. This is an interior hellscape, not a real one.

In the film's first third, ever more outlandish obstacles prevent Beau from embarking on his trip, which he's dreading anyway. It's a masterful filmic approximation of a stress nightmare. His experiences are so horrific yet so unlikely that we can't help laughing at the filmmaker's dissection of a paranoid mindset.

How did Beau become this teeming ball of fears? As he approaches the loved and feared object of his quest — his mother — we gradually find out. Along the way, Beau encounters the kindness of strangers (Amy Ryan and Nathan Lane as a grieving suburban couple), but their charity sours quickly into something more conditional and sinister. He savors the freedom to dream of a better life when he wanders into the domain of a plein air theater troupe, visually reminiscent of Vermont's Bread and Puppet Theater. But even there, catastrophe soon intervenes, paving the way for a Kafkaesque finale.

In the theater sequence and again at the end of the movie, Aster puts the viewer on the spot, asking us: Why are we watching this man be tortured (or, more realistically, torture himself)? What do we get from it?

Horror movies offer their viewers catharsis through a "safe," fictional version of ritual sacrifice, a theme that Aster explored in Midsommar. But there's no catharsis in Beau Is Afraid, no restoration of a sense of safety, perhaps because Beau isn't the innocent victim he thinks he is. The cruel but perceptive Mona offers an unsympathetic reading of his plight: Beau has a dark side that is the secret author of his misery. Sure, he had a bad childhood. But isn't it possible that he cast himself as the world's scapegoat precisely so that he could blame his mother?

Like Kafka, who had a similarly embattled relationship with his father, Aster never quite spells out this final revelation. As a result, some viewers may leave feeling as if they've watched three pointless hours of someone's Freudian persecution fantasy. For others, though, the film will resonate as a powerful reminder that we are the ultimate origins of our guilt-ridden nightmares.

If you like this, try...

Hereditary (2018; HBO Max, rentable): While Aster's breakthrough film is closer to a conventional horror movie than Beau Is Afraid, it's also about an adult child (Toni Collette, in this case) who feels terrorized by the legacy of a powerful mother.

Mother! (2017; Paramount+, Hoopla, rentable): Like Beau Is Afraid, this biblical-allegorical-environmentalist melodrama from Darren Aronofsky provoked walkouts and talk of auteur excess. Both movies number among the most harrowing depictions of anxiety ever put on film.

I'm Thinking of Ending Things (2020; Netflix): As a writer and director, Charlie Kaufman has been using absurdist surrealism to explore artistic neuroses since day one, and his adaptation of a novel about a couple's ill-fated road trip is no exception.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Beau Is Afraid"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

About The Author

Margot Harrison

Bio:

Margot Harrison is the Associate Editor at Seven Days; she coordinates literary and film coverage. In 2005, she won the John D. Donoghue award for arts criticism from the Vermont Press Association.

Margot Harrison is the Associate Editor at Seven Days; she coordinates literary and film coverage. In 2005, she won the John D. Donoghue award for arts criticism from the Vermont Press Association.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Now Playing in Theaters: May 1-7 Now Playing

- 2. Movie Review: 'Challengers' Movie+TV Reviews

- 3. Movie Review: 'Ripley' and 'La Chimera'' Movie+TV Reviews

- 4. Now Playing in Theaters: April 24-30 Now Playing

- 5. Movie Review: 'Love Lies Bleeding' Movie+TV Reviews

- 6. Movie Review: 'Civil War' Movie+TV Reviews

- 7. Movie Review: 'Scoop' Movie+TV Reviews