click to enlarge

- Alicia Freese

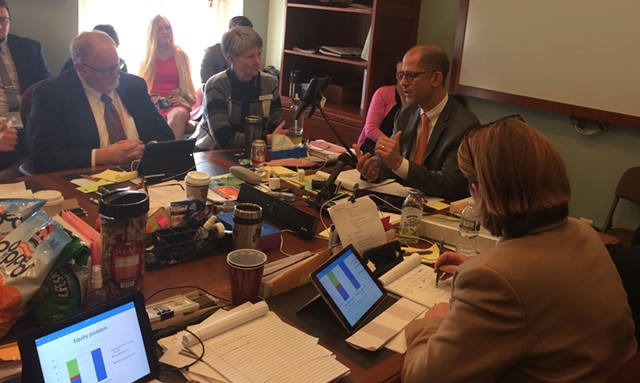

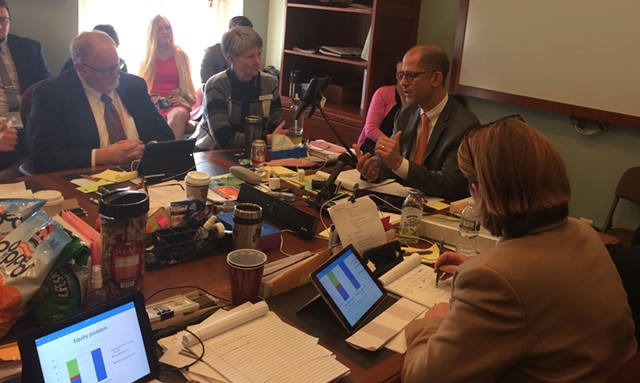

- Peter Griffin describes potential legal problems with Gov. Phil Scott’s education proposal at a House Appropriations meeting Tuesday.

Carol Brigham, whose 5th grade daughter was a plaintiff in a landmark Vermont Supreme Court case that reshaped education funding law, is traveling to the Statehouse next Tuesday to mark the 20th anniversary of her legal victory.

But the mood at the event, billed as “a celebration of Vermont’s constitutional commitment to equity,” may be somewhat tempered by what’s happening elsewhere in the building. Lawmakers are discussing whether Gov. Phil Scott’s education funding proposal runs afoul of the

Brigham decision.

Minutes after Scott finished unveiling his plan last week

to require districts to level-fund their budgets, lawmakers began expressing concern. This Tuesday, one of the legislature’s lawyers, Peter Griffin, confirmed that they have reason to worry.

In

Brigham v. State, the court concluded that Vermont — by allowing districts to supplement school funding with local property tax money — had violated the constitutional right to equal opportunity.

Summarizing the decision to members of the House Appropriations Committee, Griffin said, “You can’t have property wealth be a proxy for the amount of educational resources you get.” For that reason, “I was concerned when I saw the governor’s proposal to allow towns to raise money on their own,” he told them.

Scott’s budget plan calls on schools to freeze their budgets indefinitely, but for Fiscal Year 2018 it would allow districts to raise additional money — an amount up to 5 percent of their current spending — by levying a local property tax.

Asked about the likelihood that the state would get sued for codifying this plan, Griffin told lawmakers, “It’s probably significant.”

He also flagged two other “litigation risks.” Scott’s plan could create additional inequity because it locks in districts at their current spending rates, which vary widely.

And since the plan would require level-funding indefinitely, the state could be sued for depriving districts of adequate resources. (Scott’s plan allows funding adjustments for student population changes, but not for inflation.) Griffin said he could envision a lawsuit being brought “when someone says, in 2024, ‘Why am I locked into 2017 spending levels? That’s not enough to do what we used to be able to do.’”

A spokesperson for Scott didn’t directly address Griffin’s arguments, instead suggesting that Vermont’s current funding system violates

Brigham. “The Governor believes there is tremendous inequality in the current system — in part because the system directs so much money towards overhead costs, rather than in opportunities to increase equal access. So, perhaps it is time for a Brigham challenge so we can recalibrate and move towards its intentions for equal access across districts.”

Having delivered his

assessment to the committee Tuesday, Griffin was packing up his papers and heading toward the door. Rep. Kitty Toll (D-Danville), who chairs the Appropriations Committee, called out, “Did you have another proposal you’d like to offer up?”