Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Before the Civil Rights Act, Vermont's 'Tourist Homes' Welcomed Black Travelers

Published February 22, 2017 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated March 3, 2020 at 7:08 p.m.

In 1957, Joyce Austin traveled from Montclair, N.J., to Burlington to visit her boyfriend, Leroy Williams Jr., the captain of the University of Vermont football team. But when she arrived at the Rest Haven Motel on Williston Road, she was told unambiguously that the establishment did not "accept colored people." That incident made the Burlington Free Press because Williams was a local celebrity of sorts. But, as the Vermont chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People pointed out a few years later, for every reported incident of such discrimination, many more went unreported.

Historians have no statistics on how frequently African American visitors to Vermont were denied service during the Jim Crow era. But it's no secret that before the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, traveling while black in the U.S. was even more difficult and dangerous than it is now.

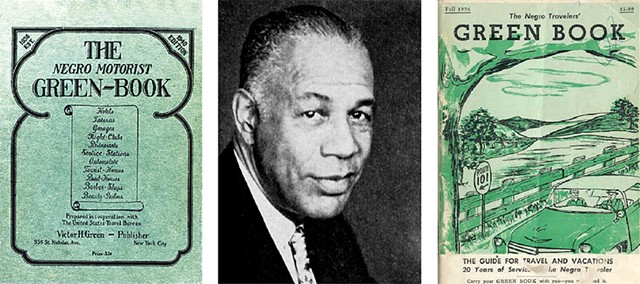

That's why an enterprising New York postal carrier named Victor Green compiled The Negro Motorist Green-Book, a state-by-state compendium of black-friendly places to eat, sleep and get gas, published from 1936 to 1967. If you were to open a copy of the book in the mid-to-late 1940s and flip to Vermont, you'd find solitary listings scattered throughout the state and three in Burlington within a few blocks of one another.

These hotels and tourist homes, the latter of which were essentially bed-and-breakfasts, provided travelers with a safe space for the night — and the reassurance that they would not experience humiliation or danger on the road. The Green-Book enabled African Americans to stop en route, instead of sleeping on the side of the road in their cars and carrying their own food and gas with them.

"There's an entire other world, a black world, that African Americans lived in that was totally invisible to white Americans," explained Gretchen Sullivan Sorin. A Green-Book historian, she's also the director and distinguished service professor of the Cooperstown Graduate Program in museum studies at the State University of New York at Oneonta.

We still lack the historical research that would allow us to accurately outline the contours of that world in Vermont. UVM associate professor Harvey Amani Whitfield discovered a small black community in the Old North End that dates to the 1880s, but his resulting article about black Burlington ends at 1900. Elise Guyette's 2010 book Discovering Black Vermont: African American Farmers in Hinesburgh, 1790-1890 ties up at about the same time, as the families she traced moved out of state.

Green-Book entries suggest a continuous African American presence in Old North End neighborhoods through the early 20th century — at least in part because of the military.

In 1909, the 10th Cavalry Regiment — 750 so-called Buffalo Soldiers — arrived at Fort Ethan Allen from the Philippines, along with hundreds of camp followers who provided services to those troops. Their presence increased the black population of Chittenden County more than tenfold.

In the weeks before the soldiers arrived, white Vermonters expressed their panic in the pages of the Free Press. Some even proposed the establishment of a Jim Crow-like system. But cooler heads ultimately prevailed, and, by all accounts, the 10th cavalry regiment had relatively pleasant interactions with the larger Burlington community.

Many retired Buffalo Soldiers decided to settle in the area. Bee McCollum is the last self-identified descendant of a Buffalo Soldier — Willis Hatcher — living in Chittenden County. She grew up in the family home in Winooski, hearing stories about the warm relationships among the soldiers and white residents.

"I think that was part of the reason why my grandfather stayed here," said McCollum, "that he would have the chance to live the remaining days of his life with a little dignity and respect."

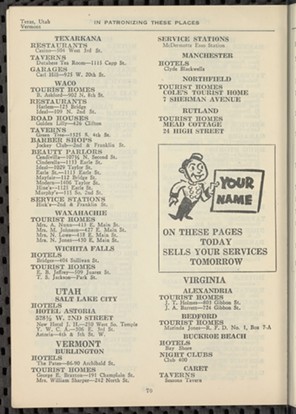

Though the daily experience of African Americans in the early 20th century is largely missing from Vermont's historical records, the Green-Book does provide a few names to research. Those names stayed the same in the guide for a number of years: Under "hotel" were the Pates at 86-90 Archibald Street; under "tourist homes," George E. Braxton at 191 North Champlain Street and Mrs. William Sharper at 242 North Street.

According to obituaries, newspaper accounts and military rolls, Frank Pate and George "Slim" Braxton came to town with the 10th Cavalry and put down roots. Although William Sharper is not listed in the Buffalo Soldier rolls, a conversation with his Connecticut-based family genealogist, Vicki Welch, indicates that he was in the military and probably arrived with that regiment, as well.

Through the Free Press archives, we can trace these men's lives over the following 30 years: their searches for work, their brushes with the law, and their marriages, divorces and deaths. Their obituaries reveal that fellow members of the tight-knit group of former soldiers served as pallbearers at each other's funerals. The group got smaller and smaller until, by the late 1950s, almost no one was left.

According to census records, Braxton and Pate, like Hatcher, began their lives in the South. Their experience was part of the larger diaspora of black Southerners moving north to seek less overt discrimination and more economic opportunities.

Braxton was born in Marietta, Ga., in 1882, enlisted in the military when he came of age and fought in the Spanish-American War before coming to Burlington in 1909. Although he began his civilian time in the Queen City as a bit of a scofflaw — he ran a club that sold liquor without a license to black soldiers and their (sometimes white) escorts — he ended it as a respectable citizen. During the last few decades of his life, Braxton worked as a handyman and general laborer and, eventually, at the Central Terminal Restaurant. His tourist home, like most others, was not a full-time business but a way to bring in a little extra income and meet interesting out-of-towners.

The newspaper published occasional announcements of visitors staying with Braxton and his wife for weeks at a time. It's unclear whether these were paying guests or friends. Braxton's name was listed in the Green-Book for a number of years after his death, indicating that his wife continued running the tourist home by herself.

Frank Pate enlisted in the army from his native Tennessee and served in the Philippines after the Spanish-American War. In 1911, he married a Filipino camp follower named Cleta, who had arrived at Fort Ethan Allen with the regiment in 1909, her young son in tow. Like Braxton, Pate ran an illegal drinking establishment catering to soldiers, and it was frequently raided.

Pate, too, changed his ways. Despite discrimination and limited opportunities, he ran a concrete business and owned an 11-bedroom home, which was listed as a hotel in nearly every edition of the Green-Book. Pate died in 1950, but the hotel continued to operate after his death, presumably run by Cleta or her son, Alfred.

William Sharper represents another facet of black New England history. Not a migrant from the South, he came instead from an old mixed-race (black, Native and white) family in Connecticut. His wife, Jenny, was born in North Carolina in 1874, so her move to Burlington may have reflected a desire to leave the violence and restrictions of the Jim Crow South.

The 1930 and 1940 censuses indicate that the couple owned a home in Burlington and took in boarders — both white and black. It's unclear whether that pattern is a sign of social integration among residents of the Old North End during that period.

"Mrs. William Sharper" also remained listed in the Green-Book after her husband's death. Sorin noted that the lady of the house often ran a tourist home for supplemental income.

Tourist homes gave such women an opportunity to meet other African Americans from around the country. In a city with relatively few black residents and no black churches or fraternal organizations at the time, the conversations with visitors were surely welcome.

Who were the black travelers passing through Burlington? Sorin doesn't have information specific to Vermont, but she theorizes that they visited for the same reasons whites did, and do: to see the foliage and beautiful sites around the state; to visit friends and family; for work; to drop kids off at college.

A number of high-profile black musicians frequented Burlington-area venues, in particular the Bayside Pavilion in Malletts Bay. It's hard to imagine celebrities such as Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong staying on North Street, given their other options; the Hotel Vermont accepted black guests, according to The Seeking, a 1953 autobiography by African American Vermonter Will Thomas. Still, when tenor and composer Roland Hayes visited Burlington in the late 1940s, Thomas writes, he was discouraged from eating in the Hotel Vermont dining room with the other guests.

A musician who wanted to avoid such ignominy might choose to stay at a tourist home instead, fussed over by the likes of Jenny Sharper and served a home-cooked meal.

The prospect of spending the night in a tourist home gave black motorists peace of mind as they explored the "lofty peaks, beautiful valleys ... and quiet villages of Vermont," as Green described the state in his 1949 vacation guide.

"They would know that, at the end of the drive, there was a room," Sorin said.

The Green-Book became irrelevant after the Civil Rights Act was passed — and that was Green's hope all along. "There will be a day sometime in the future when this guide will not have to be published," he wrote in the introduction to multiple editions. "That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication, because then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment."

The Pates, Braxtons and Sharpers were long gone when that law finally passed.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Hidden Hospitality"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: History, The Negro Motorist Green-Book, The Green Book, African American history, Black History Month, Victor Green

More By This Author

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Shaina Taub's 'Suffs' Earns Six Tony Nominations, Including Best Musical Performing Arts

- 2. Bianca Stone Named New Vermont Poet Laureate Poetry

- 3. Student Film Documents Failed Plan to Cut Books From Vermont State University Libraries Film

- 4. STRUT! Fashion Show Returns After Four-Year Hiatus Culture

- 5. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, May 1-7 Magnificent 7

- 6. Adam Tendler and the VSO to Premiere Vermont Composer Nico Muhly’s First Piano Concerto Performing Arts

- 7. Amalia Angulo’s Drawings at Kishka Gallery Suggest and Question a 'Peaceable Kingdom' Art Review

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 5. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 6. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse