Published July 22, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated July 23, 2015 at 5:36 p.m.

For those of us who grew up with D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths (or discovered this weird, wonderful book with our own children), the myths and exploits of the ancients retain a powerful hold. They evoke a time when humans and gods, monsters and oracles, brushed past one another in an everyday way.

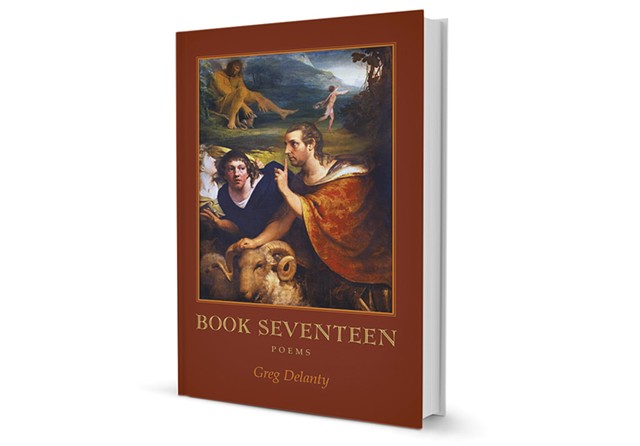

Irish poet Greg Delanty, who is poet-in-residence at Saint Michael's College in Colchester and author of nine previous volumes of poems, draws on this lasting appeal of the ancient topoi in his new book, released as The Greek Anthology, Book XVII in the UK and now as Book Seventeen in the U.S. By presenting his work as a collection of newly unearthed "ancient" pieces, Delanty places it in a long and illustrious tradition that merits some explanation.

The 16-volume Anthologia Graeca, an accumulation of epigrams, songs and poems spanning 1,700 years of Greek literature, is one of the earliest anthologies — the Greek term meaning "a collection of flowers." Found in various manuscripts from the 10th and 14th centuries, the so-called "Greek Anthology" includes terse epigrams, off-color jokes, laments, diatribes and anecdotal portraits of contemporaries and deities.

The Greek Anthology has exerted a sustained gravitational pull on European literature from the Roman era and Renaissance through the 20th century. Its influence is reflected in essential works by writers as varied as Propertius and Martial; Alexander Pope, Andrew Marvell and Walter Savage Landor; the modernists Ezra Pound, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) and Constantine Cavafy; and the underappreciated Edgar Lee Masters, whose Spoon River Anthology is a panoply of small-town personages confessing and confiding in their own verse epitaphs.

The poems that have come down to us from those old Greeks themselves (Archilochus, Asclepiades of Samos, Callimachus and many more) have been translated repeatedly not only by scholars but also by excellent poets, including Kenneth Rexroth, Willis Barnstone, Daryl Hine, Rosanna Warren, Anne Carson and part-time Vermonter Rachel Hadas. In translation, the Greek poems have tended to share with ancient Chinese poetry a distinct formal compression, descriptive concision and conversational manner.

Like those of his predecessors, Delanty's neo-Greco poems are brief. Mostly appearing two to a page, they're clustered by theme (e.g., time and its costs, political chicanery, eros, the splendor of the natural world), and their tones range from gloomy to bawdy. These aren't dutiful imitations or parodies of classical antecedents but fresh visitations, remarkable in their metaphorical ingenuity. Delanty has found and fashioned sounds that genuinely recall the miscellaneousness of his exemplars, rich and thick with the physics of existence and poignant with emotional restraint, often quietly rhymed.

And Book Seventeen is fun to read, as Delanty hip-hops between epochs, at times echoing age-old tropes and settings and then leaping to up-to-date, altogether recognizable details. In "Driving in Vermont," he describes the annual "plumes of leaf-fire" that "people travel thousands of miles to admire":

Folk drive by, their radios reporting the weather, last night's frost, baseball, the demise of the world in the umpteen ways we've devised. Maybe a few comment on the glorious light, everyone hightailing it to work. But now my job is to pull off Route 15 in Hyde Park and Centerville and report this sighting. Who'd have thought the god of light would be seen in the Northeast Kingdom, Apollo himself, on the lam from his Attic stomping ground.

"Attic" refers to the main dialect of classical Greek spoken in the region around Athens. That's an example of Delanty's erudition, a sly allusion that doesn't interrupt the rhythm and momentum of the poem at hand.

Many of these poems are didactic, in the etymological sense of "teacherly": They pose an ethical or psychological quandary and then craft an instructive resolve. Delanty keeps striking parallels, explicit or implicit, between the cosmos where our forebears struggled through life — laboring and loving and inevitably aging — and our day-to-day universe of jobs, families, cars, meals, the weather, even mischievous gods and (in one poem) lobsters. His poems are colloquial but never chatty; there's a strong, taut sense of form at work (and at play) in each line.

In "Terminal," here quoted whole, the poet calls a sick friend by the name Tithonus, referring to the mythical figure who was made immortal by Zeus at the behest of his divine lover, Eos (or Aurora, the dawn). Alas, Eos forgot to request eternal youth, so Tithonus' body continued to decay, just as Delanty's patient decays while being kept alive indefinitely in the oncology ward:

And so, Tithonus, you're hooked to ventilator, catheter, or cannula, gagging down another pill, unable to fend for yourself. You pray to be released from the drip as malignant cells metastasize, make nothing of you. Dawn even abandons you in the snug-as-a-coffin terminal room. Nurses turn you, change your diaper. You're unable to recall your own name, remember you can't remember; eternally aware dementia erases the spool. The gods, as usual, show no mercy.

Even when writing with utmost severity, Delanty is enjoying himself.

In "Recycling," he remarks on his own technique, which entails continually shifting the perspective from microcosm to macrocosm: "If myths are frameworks, then any one person's story / is made from a scrap heap: a Cyclops here, / Chimera there, Asclepius one minute, Persephone the next. / Each is like a bicycle put together from old parts: / a rusty chain, racer handlebars, mudguards, an odd tire."

My one quibble with this fine book is that the table of contents attributes the poems to a delightfully motley roster of poets: "Grigorographos," "Deanos the Bearded," "Rovius Flaccus," "Rosanna Daedalus," "Terence of the North." Surely these monikers, concocted by Delanty, are canny nods and greetings to friends and illustrious peers. The names are enjoyable to read and think about, but they don't appear in the body of the book alongside the poems themselves, although the handsome page layout could have easily accommodated them. This seems like a missed opportunity.

In a short preface, Delanty hints that Book Seventeen may bequeath a sequel, perhaps next time with numerous poets involved. We look forward to them all inventing personae and improvising on the 2,000-year-old lineage that seems as irrepressible as that ever-upwelling Hippocrene fountain that the hoof of Pegasus struck open on the slopes of Mount Helicon.

From Book Seventeen: Poems

Disarming

A middle-aged woman—plain you might say—strolls by our house. I was out of sorts, not long up, but her serene smile, without saying a word, remarks: "Take in the sun on the lake, the honeysuckle's pink fingers bursting into yellow flames, the traffic on North Avenue for once gone so quiet you can hear the whir of the hummingbird's wings reversing in midair." On another morning such serenity would have vexed me, but there is something so natural about her demeanor. She doesn't notice me. Disarmed, I let what bothers me go and think since there's no corresponding god —the pantheon being all tiresome piss and vinegar— we must create a new order and call her Tranquilia, Calmes, or promote Halcyon and tell Aphrodite, Ares, Artemis, even Zeus, to move over in the pecking order, set her smack in the middle, the woman who breezes by our house this divine morning.

The Other

Time to raise a paean to the carrion flies, olive-green slugs, mauve maggots, slime-emerald algae, dandruff-creamy worms; to all who make nothing of the corpse. The skin-crawling bugs we turn our heads away from, the loathsome swarms, the steaming dung dolloped on the soil that springs roses, potatoes, tomatoes, the food on our tables. Doff our hats to all the matter and mites we look down our snotty noses upon. Admit that we are blind, hoodwinked, dumb, bats —praise the bats too— that we are the great ungrateful. Give thanks, erect monuments to them, the other beautiful.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Among Gods and Lobsters"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Bianca Stone Named New Vermont Poet Laureate

May 1, 2024 -

What Louise Glück Wanted 'Was to Be Understood'

Dec 20, 2023 -

Former Vermont Poet Laureate and Nobel Prize Winner Louise Glück Dies at 80

Oct 13, 2023 -

UVM to House Grad Students in Saint Michael's Dorm

Jul 28, 2023 -

Saint Michael's Launches Racial Equity Graduate Program

Mar 29, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.