Published February 4, 2015 at 10:00 a.m.

The life and thought of longtime Burlington resident Murray Bookchin can be read as a profile in courage.

Never a slave to political fashion, he made intellectual enemies among former comrades in the communist, socialist and anarchist wings of the American left by challenging their cherished dogmas. At the same time, he remained consistently radical, ultimately crafting a political philosophy that has proved prophetic and may turn out to be profoundly influential — even life saving.

So who was Murray Bookchin?

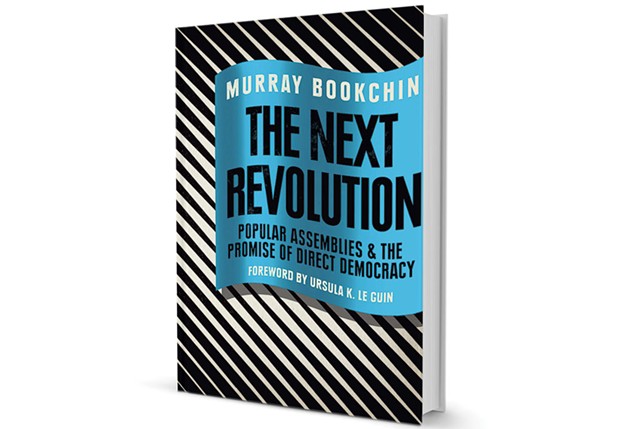

The uninitiated can find answers in The Next Revolution: Popular Assemblies and the Promise of Direct Democracy, a recently published sampling of Bookchin's writings coedited by his daughter, Debbie Bookchin; and Blair Taylor, one of Murray's keenest intellectual acolytes. Both editors are active in the Institute for Social Ecology, a small Vermont-based think tank that stands, precariously, as Bookchin's institutional legacy.

Renowned novelist Ursula K. Le Guin has written a brief foreword to this 220-page volume published by Verso. Le Guin, herself an imaginative social critic, encapsulates one of Bookchin's key insights when she identifies capitalism's incessant, indiscriminate pursuit of economic growth as the cause of the worsening environmental crisis. "We have, essentially, chosen cancer as the model of our social system," Le Guin dryly remarks.

Most of the nine Bookchin essays chosen for The Next Revolution were written in the 1990s, with the latest — "The Future of the Left" — completed in 2002, four years before the author's death at age 85. The essays offer an accessible overview of Bookchin's thinking, focusing on his development of a political philosophy that can be referred to, more or less interchangeably, as communalism, libertarian municipalism and social ecology.

The book is an exercise in erudition. Bookchin became intimately acquainted with revolutionary ideologies during a lifetime on the left, beginning at age 9 with membership in the youth wing of the Communist Party USA and passing through periods as a Trotskyist, libertarian socialist and anarchist. In this collection he dives into the depths of each, making frequent references to old-school belief systems and the figures associated with them.

The Next Revolution is no breezy page-turner, but Bookchin's style generally avoids academic pomposity. Even readers who are new to this subject matter won't find the book overbearingly esoteric.

Le Guin suggests in her foreword that Bookchin's ideas are sufficiently trenchant and attractive to survive him, although she can't be accused of intemperate enthusiasm. "So in a country that has all but shut its left eye and is trying to use only its right hand, where does an ambidextrous, binocular Old Rad like Murray Bookchin fit?" Le Guin asks. "I think he'll find his readers," she predicts demurely.

Bookchin's chances of staying relevant rest partly on his unsparing, insightful critique of formerly dominant left-wing doctrines that many of today's younger activists consider antiquated. He blisters Marxism for a "workerist" obsession that blinded it to the progressive potential of gender-focused movements, as well as to the existential threat of climate change. Anarchism, Bookchin argues, has too often served as a philosophical alibi for self-indulgence.

And, unlike most anarchists, he doesn't see political power as an inherently negative dynamic that must somehow be destroyed. Power will always exist, Bookchin posits, and can and should be used to advance positive agendas.

Capitalism utterly changed the world during the 20th century, while communism and anarchism failed to change, or evolve, in response, he writes.

Bookchin didn't live to see the emergence — and collapse — of Occupy Wall Street, but he would surely have disparaged its means while endorsing its ends. Revolutionaries will be making a major tactical mistake, he warned, when "we fetishize consensus over democracy in our decision-making process." Efforts to achieve consensus often waste time, frustrate many of those involved and cause movements to stagnate, Bookchin observed. Besides, he added, leaders will inevitably emerge, even if they are not formally acknowledged.

Yet Bookchin's alternative, communalism — defined as "a system of government by which virtually autonomous local communities are loosely bound in a federation" — is intrinsically opposed to hierarchies. The "libertarian municipalism" that he espouses, while a wonky term that doesn't lend itself to soundbites, is manifested through neighborhood-based assemblies in cities. In them, people practice politics, which in Bookchin's view, means they "democratically and directly manage their community affairs."

Despite his insistence on free thinking, Bookchin can be doctrinaire at times. Running for elected office, he maintains, is a worthy endeavor only on the most local level. Revolutionaries are almost certain to be corrupted, or co-opted, if they seek votes on the statewide or national level, he contends. Somewhat similarly, in his blinkered view, the capitalist economy will never make space for green enterprises.

Eco-entrepreneurs are certain to be "devoured" by competitors in a marketplace that "rewards the most villainous at the expense of the most virtuous," Bookchin suggests. Trying to imbue corporations with environmental sensibilities, he adds, is "like asking predatory sharks to live on grass." Bookchin offers a down-home example in characteristically polemical terms: "I have seen a self-styled 'moral' enterprise, Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream, grow in typically capitalist fashion from a small, presumably 'caring' and intimate enterprise into a global corporation, intent on making profit and fostering the myth that 'capitalism can be good.'"

Bookchin's fiery formulations sometimes sound like something out of the Old Testament. That's actually in keeping with his stature as a prophet of end times.

Bookchin sussed out the severity of the planetary ecological crisis long before progressives awoke to the degradation of the natural world that is being wrought, in his words, by "growth, growth and more growth." His warning against the industrial plundering of the planet, Our Synthetic Environment, was published six months prior to Silent Spring, Rachel Carson's seminal 1962 book on the same theme.

And how about this perspicacious insight into the causes of Islamist terrorism? "Most of the 'fundamentalisms' and 'identity politics' erupting in the world today," Bookchin wrote 13 years ago, "are essentially reactions against the encroaching secularism and universalism of a business-oriented, increasingly homogenizing capitalist civilization that is slowly eating away at deeply religious, nationalistic and ethnic heritage."

Unusually for a visionary, Bookchin was modest in his expectations.

Libertarian municipalism, he cautions in "The Future of the Left," "will have only limited success at the present time." Its advocates "must be prepared to endure more failures than successes," he adds.

Let's hope that the successes will soon outweigh the failures. It's hard to see a viable way forward, politically and environmentally, that doesn't draw at least some guidance from Bookchin's philosophy.

Debbie Bookchin will talk about her father and The Next Revolution on Saturday, February 21, 2 p.m., at Phoenix Books in Burlington. phoenixbooks.biz

The original print version of this article was headlined "A Vermont Radical Offers Posthumous Guidance for the 'Next Revolution'"

More By This Author

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.