Published April 25, 2012 at 10:44 a.m.

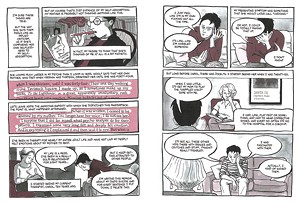

Fans of Vermont cartoonist Alison Bechdel’s best-selling 2006 memoir, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, which recounted the story of her closeted gay father, have long anticipated a follow-up. This spring, the wait is over, as Bechdel turns her retrospectoscope to the other parent with a second memoir, Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama.

It’s been quite an eventful spring for the veteran comic-strip author, creator of the long-running “Dykes to Watch Out For.” This month she received both a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from Publishing Triangle, an organization devoted to LGBT people in the book industry. This week, Judith Thurman profiles her in the New Yorker.

Last month, Seven Days visited Bechdel at her Bolton home to learn more about the process and the pain behind the new memoir.

SEVEN DAYS: How do you get yourself in the headspace to do this kind of personal work? Can you just switch it on, or does it take you a while to transition?

ALISON BECHDEL: This book was excruciating. My editor was talking to me the other day and saying, “Most people take six years to get a PhD; it takes you six years to write a book.” I just really kind of turned my life over to it. It was a long, difficult process. I got depressed while I was working on it. I got really anxious. I got filled with shame — like all these things I was writing about, I had to go back and live through.

I had another proposal for it [called Love Life, about the steps of falling in love], way before I knew what I was doing. [But four years in] my agent looked at what I had written and she said, “You know, this really doesn’t make any sense.” I realized she was right. I was avoiding telling the story of my mother by using that crazy laborious “love-life” framework. I’d say that I threw it out and started over, but really, I just kind of reassembled it, like bricks that I had to put together in a very different way.

SD: What you figured out in psychoanalysis is a major theme of the book. Why did you choose psychoanalysis instead of cognitive behavioral therapy or Eckankar or anything else?

AB: Part of it is just the happenstance that I was working with a therapist who was in the process of becoming an analyst, so I heard a little about it from her. I really respected the kind of work that she did. I know a little bit about CBT. It seems totally superficial to me, like it doesn’t get at the root of things. I’m sure it helps take the edge off things for people, but I don’t want to take the edge off — I want to get really, really down in it. I know most people think [about psychoanalysis], Oh, this stuff is bullshit. And I can’t do anything about that, but I didn’t write the book for them.

SD: Do you think part of the usefulness of psychotherapy is because it’s so literary? It’s sort of about shaping yourself into a story, or finding a story in all of these details.

AB: I think it’s more about images. What is compelling to me is how the unconscious uses images. And, in telling a visual story, I just realized I had this really amazing potential to arrange images in a way that not [only] reflected what was going on in my unconscious, or how the unconscious works, or how therapy works, but [also] solved my own problem visually. I started to see these parallels, like the way that the spider that my mother was afraid of kind of looks like the splatter of vomit on the floor, which is my phobia. I’m not drawing any hard-and-fast conclusions about those things, but I’m just seeing how images are linked in a narrative way.

SD: How has your mom reacted to this book? Has she read it?

AB: Yes, she has. I’m used to this by now, but she has not responded to the substance of the book, merely to the fact of it. She’s not going to confirm or deny anything. She’s not going to comment on my writing skill or lack thereof. The book is getting good prepublication reviews, and she’s really psyched about that, even though one of them described my relationship with her as “substantive though essentially external.” I really think that that does not bother her. I think she likes the “substantive” and she agrees with the “external” and is fine with that.

SD: [Spots and points inquiringly at a stray copy of lit-critic James Wood’s book How Fiction Works.]

AB: My mom just gave that to me! It’s fascinating. I think it’s a subtle message from her that she wishes I would start writing fiction.

SD: Do you do this work because you have to — because it’s coming out of you — or do you do it thinking, This is how I’m going to make the world a better place?

AB: In my youth, I was more I have to make the world a better place, and now I’m more like, I have to write this; it has to come out. But I still feel like there is a similar mission. I couldn’t see that until recently, but what I was doing with “Dykes to Watch Out For” was creating a reflection of myself in the world. I wanted to see images of women like me and my friends, and I wasn’t seeing them anywhere in the culture in the early ’80s. So I decided I would make them myself. That was a very pressing mission for many years. I feel like I was part of the success of [the LGBT] movement in the culture, and it enabled me to then go on to tell this very queer story about my own family that I couldn’t have told to a broader audience when I was younger — it wasn’t possible; no one was interested; it was unacceptable. It was a much more personal project, not a political one like Dykes was. [Instead of] Yeaaah, I’m gonna represent lesbians, it was more like, I’m gonna represent my dad and my family.

With this book about my mother, I’m curious about the function of reflection itself. Why do we need that? What does having a false reflection do to people? How do false reflections and oppression work together? How does internalized oppression work? I’ve just been involved in this massive narcissistic project of looking at myself in the mirror, creating a reflection of myself in one way or another for my whole life. ’Cause I didn’t get one. I didn’t get it at the beginning. I know that sounds really whiny. My parents gave me so much, but there was a way that they couldn’t see me, and I had to see myself, and this is the lengths I had to go to. I’ve just drawn the most insanely detailed self-portrait I could muster, basically.

SD: Does the “lesbian cartoonist” distinction matter to you now like it may have in the past?

AB: No. It used to be very important to me. I was a lesbian cartoonist because anything else was copping out or giving in. But that started to change as the measure of acceptance shifted, and I realized that I didn’t need to be limited to being a lesbian cartoonist — that I could be an American cartoonist. At first that was a really radical thought to me. I was so self-ghettoized in my brain that I couldn’t quite see how that is possible. But somehow it has worked out. Even now my DTWOF work seems to have gotten grandfathered into the canon, like people refer to it as if it’s some legitimate comic strip.

SD: Of course it is.

AB: Yeah, but it didn’t use to be! It’s so funny to me.

SD: You wrote in the book that being a lesbian “saved you.” Did finding yourself at odds with expected norms make you grow as a person or as an artist?

AB: Being a lesbian saved me because it pulled me out of my mind. Even though my coming-out process was very internal and happened all in books — I basically came out through reading books and identifying with the characters in books — then I actually went out in the world and found girlfriends and people to have sex with, and relationships with. If it had just been heterosexual desire, I might not have had to think about it. I would have just done it and ended up in some dysfunctional relationship like my mother did. This is such a platitude, but it’s challenges that make us grow, and the challenge of grappling with being sexually different in this culture was really helpful for me. I always feel like it was a gift, like a bonus.

"Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama" by Alison Bechdel, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 304 pages. $22. Bechdel will read at the Flynn Center for the Performing Arts in Burlington on June 16; at Galaxy Bookshop in Hardwick on June 19; and at Bear Pond Books in Montpelier on June 26.

More By This Author

Speaking of Comics

-

Williston's Champion Comics & Coffee Combines Two of Nerdom’s Favorite Things

Apr 12, 2023 -

Tillie Walden to Become Next Cartoonist Laureate of Vermont

Mar 3, 2023 -

Origin Story: How Burlington’s Earth Prime Comics Helped Unite Vermont’s Comics Lovers

Mar 2, 2022 -

Video: Alison Bechdel Shares 'The Secret to Superhuman Strength'

May 6, 2021 -

A Virtual Welcome to Vermont's New Cartoonist Laureate, Rick Veitch

Apr 2, 2020 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.