Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

De-Stress Signals: Coping With Anxiety in 2020

Published October 14, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 23, 2020 at 2:52 p.m.

In the year 2020, humanity is plagued by myriad crises — one of which is a literal plague. And that's led to a measurable rise in stress among Vermonters. For example, according to an August report from the state Department of Health, young adults ages 18 to 25 report decreasing interest in doing things they used to enjoy, and increased anxiety and depression, since the pandemic hit Vermont in March.

Mental health professionals around the state say they have been overwhelmed by the numbers of Vermonters seeking relief from stress, anxiety and grief.

"I've definitely seen an increase in phone calls and inquiries," said Danielle Bergeron Ingram, a Middlebury-based psychologist and vice president of the Vermont Psychological Association. She believes her colleagues have had similar experiences.

"I've seen an increase in anxiety based on finances, political unrest, people worried that they're gonna be laid off, worried about navigating childcare and homeschooling," Bergeron Ingram continued. "It's definitely different since March, during the lockdown, than it has been in the last five years of [my] private practice."

She noted that, like everyone else, therapists are just trying to figure this shit out as they go along.

"We're all in this together, and it's a collective trauma," Bergeron Ingram said. "Therapists have never experienced a global pandemic, either, but we're doing the best we can to help as many people as we can."

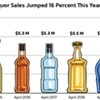

The indicators of rising stress are everywhere. Seven Days reported in May on the statewide uptick in alcohol sales — 16 percent in April alone — as many Vermonters turned to the bottle to soothe frazzled nerves. The rate of opioid overdoses is up, too — 29.1 nonfatal overdoses per 10,000 emergency department visits in July 2020, compared with 15.1 in July 2019.

In turn, Vermont substance-abuse services have reported an increase in demand. To help meet that demand, earlier this year the state departments of health and mental health received $2 million in emergency federal relief funding.

Emotional stress takes a toll on physical health, with potentially grave consequences.

Dr. Prospero Gogo, a cardiologist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, said his department has seen a spike in heart attacks. That anecdotal observation is supported by national studies, such as a recent one by the American College of Cardiology that documented a dramatic increase in cardiac symptoms in patients around the country.

Gogo noted an increase in "non-coronavirus mortality" nationwide, meaning death from, well, everything else, including cardiac events. That's not unusual, he said, when people experience large-scale traumas.

"We have good literature showing that the rate of heart attacks goes up during the wildfires in California, volcanoes in Italy," he said. "Very stressful, large-population events do increase heart attacks and cardiac presentations."

Traumatic events tend to trigger a specific kind of heart attack: stress cardiomyopathy, meaning stress on the heart muscle. Typically, Gogo explained, this is related to a surge of hormones such as adrenaline following a high-stress event — witnessing the death of a loved one, for example.

The pandemic has another potentially deadly side effect: Fearing infection with the coronavirus at the hospital, people delay care for a range of ailments. When it comes to heart attack symptoms, Gogo said, "the earlier you seek attention, the more likely you are to survive."

As for avoiding stress conditions in the first place, the cardiologist offered predictable recommendations: Eat well, exercise, don't drink to excess. Living clean can be a tall order when anxiety feels monumental, yet that's precisely when we should try to clean up our act.

Where do we start, though? In this solution-oriented package, Seven Days reports on ways to take better care of our mental health, from finding a therapist to discovering a niche hobby to learning how past traumas can help us navigate the present. (Also: Can a comic book educate us on some of these issues? Read about one coproduced by the Center for Cartoon Studies.)

While we offer a few suggestions here, the possibilities for de-stressing your life are as limitless as your imagination. As Gogo put it, "I advise whatever healthy stress-relief valve you can find."

Consider that a prescription.

— D.B.

Head Strong

Asking for help and getting the most out of therapy

Are you having trouble sleeping? Are you eating way more or way less than you should? Has your evening nightcap turned into two or four or six Manhattans? Do you no longer take pleasure in things you used to enjoy? Are you unmotivated or irritable? Did that very question just piss you off?

Congrats! You are alive in the year of Oh, Lord 2020. And it might be time to find some help.

"Those are all the big red flags of depression and anxiety," said Danielle Bergeron Ingram, Middlebury psychologist and vice president of the Vermont Psychological Association.

If you are experiencing any or all of the aforementioned symptoms, or others, take heart: You're not alone. In fact, you might have to be inhuman not to experience at least a little sadness and anxiety over the pandemic and the election and the civil unrest and the murder hornets and the wildfires and the hurricanes and Eddie Van Halen and... We need a minute here.

...

...

...

Gaaahhhh!

...

OK, we're back.

Point is, we're living in a seriously messed-up time. It's natural to feel messed up, too. But operators are standing by, and lots of people out there want to help. At the top of that list are mental health professionals: psychologists, counselors and therapists who are trained to un-mess you.

But how do you find them? And what can you expect when you do? Bergeron Ingram offered her advice.

Everything sucks. How do I find someone to talk to?

If you're looking for a therapist, Bergeron Ingram said, an easy place to start is the Psychology Today or Vermont Psychological Association websites, which both have directories of mental health professionals practicing in Vermont. Among other things, you can filter by geographic location, insurances accepted and specialty — grief, couples counseling, addiction, etc.

Once you've found some candidates, Bergeron Ingram said, vet them. "Ask questions about training and experience," she advised. "Be really specific with what it is you need help with: 'I have this need. Do you have training treating that need?'"

She added that a patient-therapist relationship is not a marriage, so it's OK to play the field.

"Just because you called one therapist does not mean you're locked on their couch for the next 10 years," Bergeron Ingram said.

She suggests having consultations with a few providers before deciding someone is right for you. If they're not, politely ask for a referral.

OK, I've found a shrink I like. What now?

First off, don't expect therapy to cure you overnight. It's not magic. Like physical ailments, mental and emotional healing takes time and, most importantly, effort. But here's the good news: The simple act of talking about what's ailing you is a great place to start.

"Having an unbiased person to talk to, really about anything, can help minimize stress," Bergeron Ingram said.

The goals should be having an outlet and coming up with an action plan to tackle your symptoms. "It can normalize stress," she said. And that can make handling stress a little less daunting.

Therapists are people, too; on top of everything we're all struggling with, they're trying to help others. How do they deal?

"How do we practice what we preach?" Bergeron Ingram asked. "We try to do just that: Practice what we preach. The things that therapists do are things I would recommend to my patients."

That means setting appropriate and healthy boundaries in personal and professional relationships and knowing their stress levels and tolerances. It also means maintaining a normal schedule and doing the things that we all know, deep down, we should be doing to stay healthy.

"Moving our bodies regularly and eating healthy food, getting rest and really listening to our bodies," Bergeron Ingram clarified.

Those things take on added importance when our lives revolve around computer screens more than ever and even therapy happens online. "It's been very taxing staring at a computer screen all day," Bergeron Ingram said.

So make a concerted effort to unplug. Your dried-out eyeballs will thank you.

This is all great advice, but I just feel so helpless. Anything I can do day-to-day?

"We're living in a world where we feel like we're out of control," Bergeron Ingram said. "Not knowing when the virus is gonna end; not knowing when we'll stop homeschooling our children; attending numerous Zoom meetings.

"I think it's really important to look at the things we can control," she continued. "Even if it's something simple, like 'I know what I'm having for dinner.' That's something you have control over. You're fueling your body and your brain, and it's something to look forward to at the end of the day."

— D.B.

For more on the Vermont Psychological Association, including a directory of local therapists, visit vermontpsych.org.

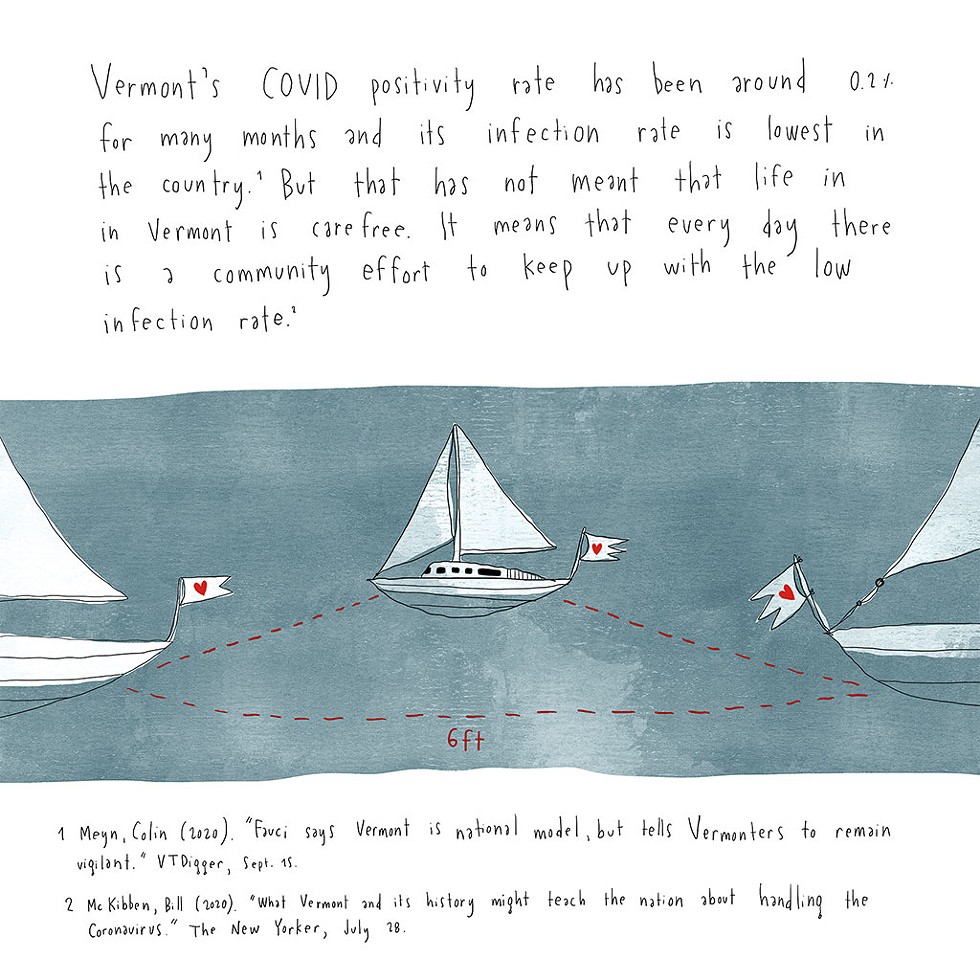

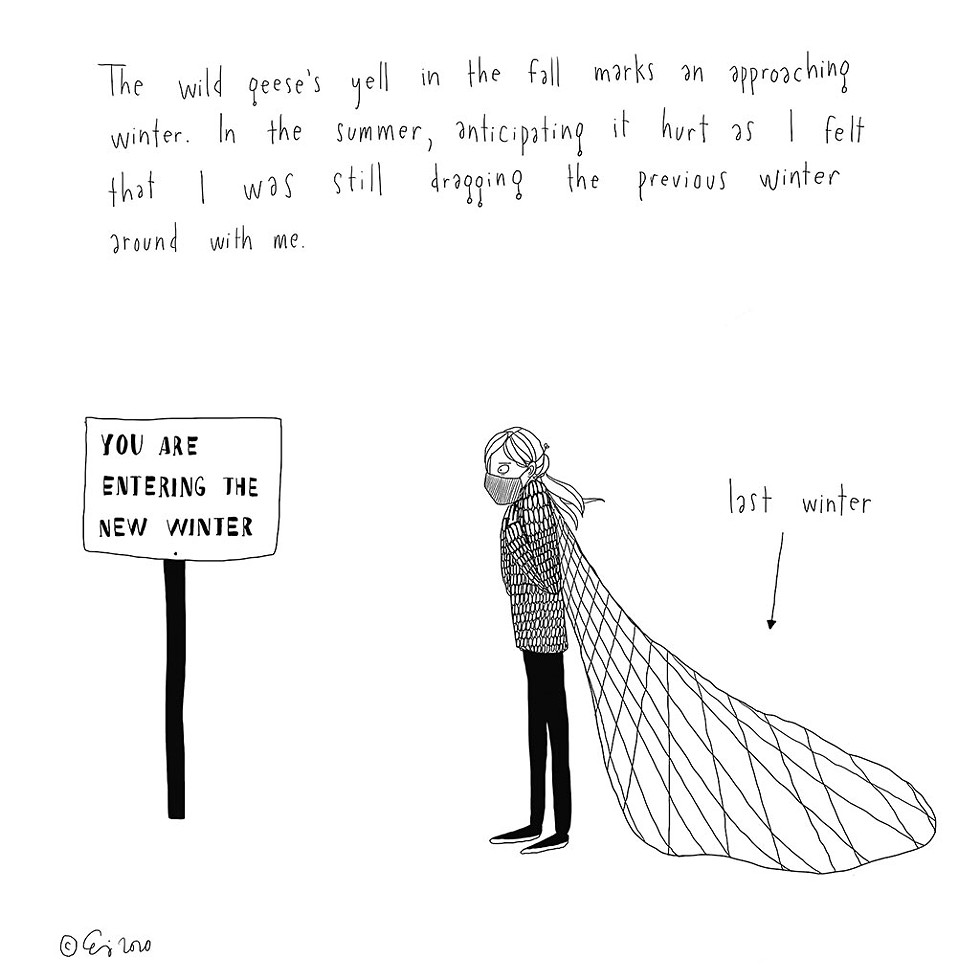

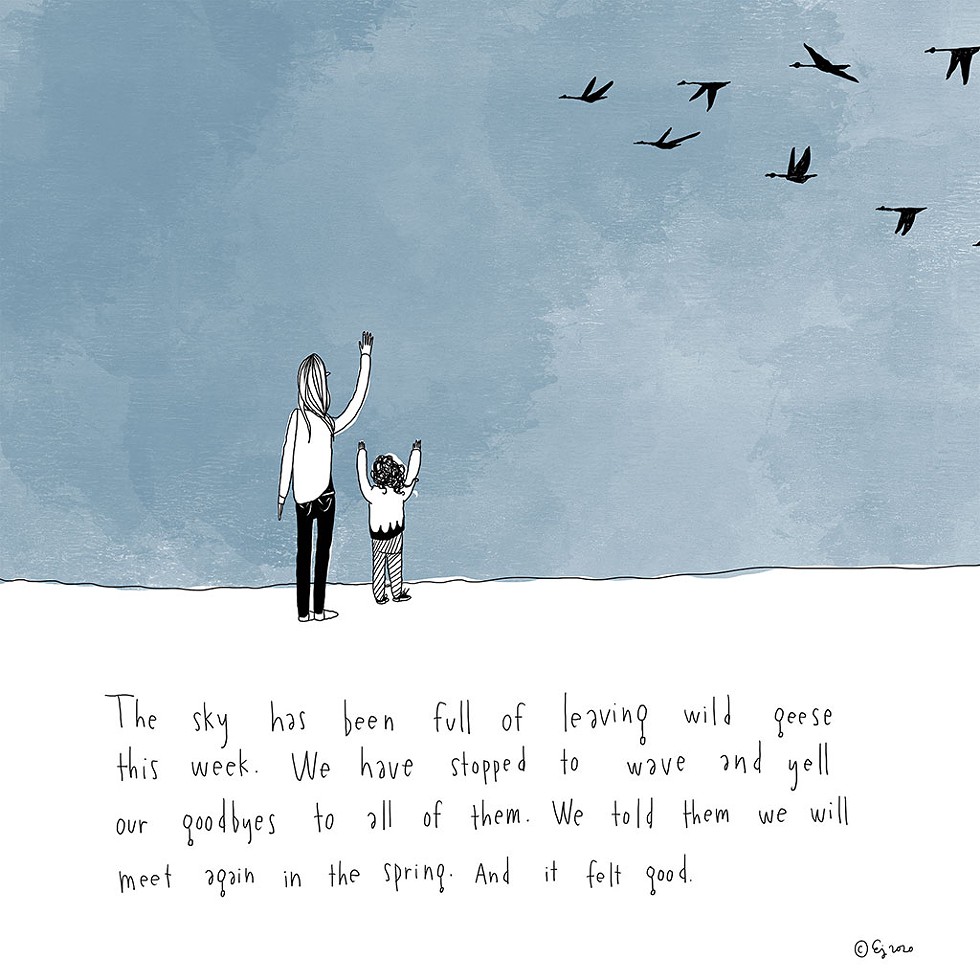

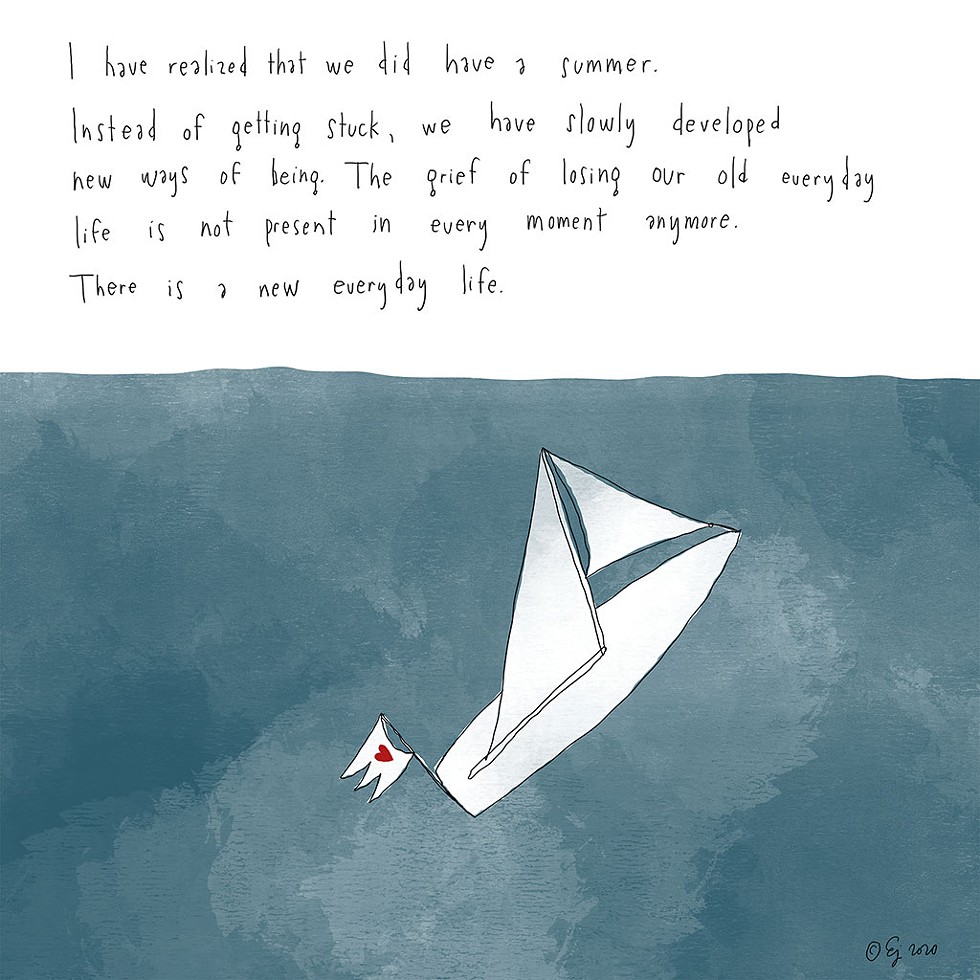

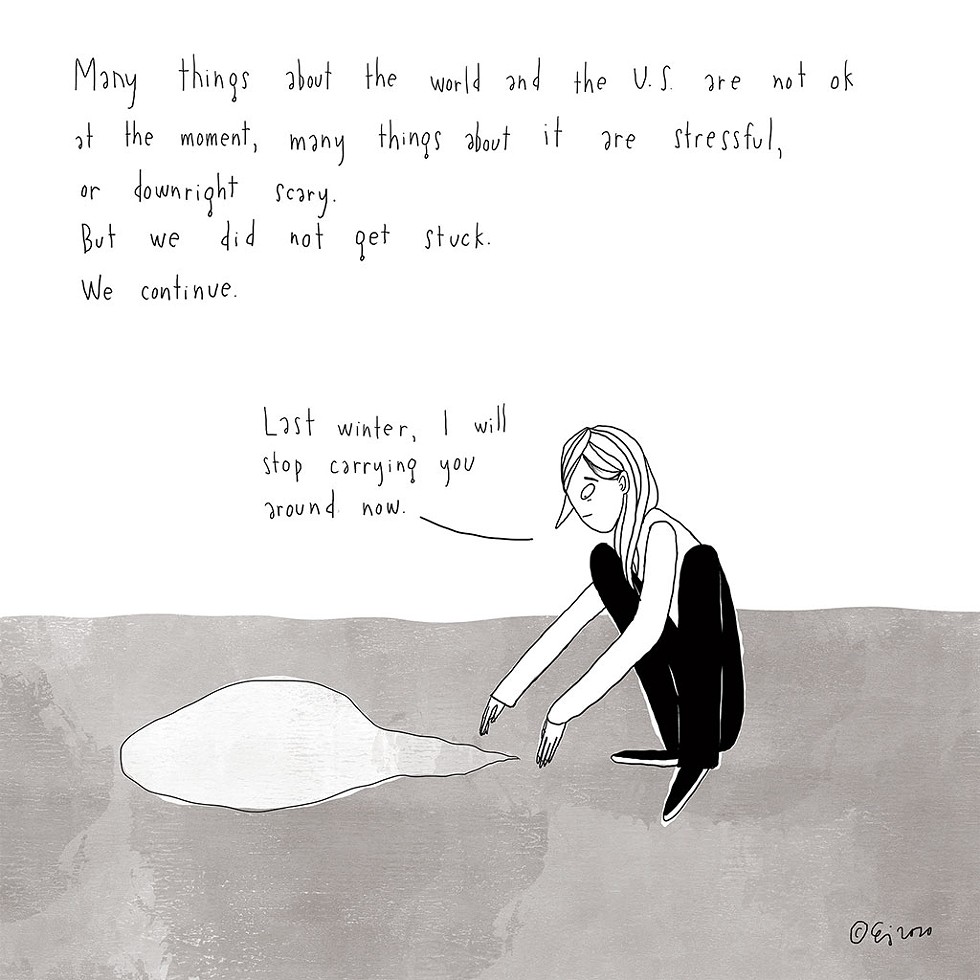

Those Weeks of Sailing

by Elisa Järnefelt

Roll With the Punches

Combating stress with a niche hobby

When I started punch needle rug hooking last winter, the hobby created more stress than it relieved. Stitching heavy-duty rug yarn into a piece of monk's cloth, stretched and secured across a wooden lap frame, was harder than I'd thought. When I wasn't losing the end of the yarn in the skein, the frame's gripper strips were grabbing my sweater sleeves, leaving trails of tiny holes. I accidentally stabbed myself in the leg with alarming frequency, sometimes drawing blood.

Undeterred by the hazards of learning this folk art and craft, I diligently punched along, hoping I'd end up with something that resembled a rug.

Punch needle rug hooking differs from traditional rug hooking in the tool used and the direction of effort. In the former, a punch needle repeatedly pushes yarn down into the cloth; in the latter, a crochet-like hook pulls it up from below.

As I practiced, the motions of stitching the yarn and gliding my Oxford punch needle across the cloth became muscle memory, and my hobby got less stressful. Watching my stitches fill the frame, I realized I'd completely forgotten about the shitstorm out in the world. I was punching away my worries, and all that mattered was the rug.

Amy Oxford invented the wooden-handled tool used by most punchers 25 years ago in Cornwall, Vt. In a recent phone call, Oxford told me I wasn't alone in my pandemic-era hobby: She's seen a 24 percent increase in sales of her Oxford punch needle since March.

When Oxford started punch needle rug hooking in 1982, it was a dying art. Compared with traditional rug hooking, punching was obscure — even frowned on.

"It was the black sheep of rug hooking," Oxford said with a chuckle.

Not bothered by what she called "crafting snobbery," Oxford vowed to keep punching alive. She started a teacher certification program, through which she's taught thousands of students to punch over the years.

In 2016, Toronto-based Arounna Khounnoraj's modern designs went viral on social media, and punching entered a new renaissance. In 2019, Oxford's company shipped punch needles to 62 different countries.

I somehow missed the 2016 wave, but I'm thrilled to have discovered punch needle rug hooking in the stress tsunami that is 2020. Punching has many attributes that make it appealing in these uncertain times: The whole point is to stab, stab, stab cloth with a sharp metal object! Thread your needle and channel your rage!

Oxford captured the craft's allure perfectly on her website. "I have seen it wash away sadness, awaken creativity, build confidence, and forge friendships. I've watched slow and patient punching bring calm, and witnessed aggressive punching dissipate intense anger and frustration," she wrote.

As I fire off row after rage-filled row, my frustration tends to melt into focus. The repetitive motion — something many handicrafts share — lowers my heart rate and unclenches my jaw.

"It's an activity that encourages mindfulness," Oxford explained. "It requires concentration on so many levels: physical coordination, visual, hand-to-eye coordination, tool-to-backing coordination, artistic thought of what you're trying to create and how you're going to create it."

It's also reasonably affordable. An Oxford punch needle costs $32; Oxford's gripper strip frames start at $69, but a regular embroidery hoop works, too. I've purchased hand-dyed yarn for $14 a skein, but leftover bits and regular craft-store yarn do the job.

Even when it's not rage-filled, punching makes quick progress. The speed with which I completed my first project — an outline of a mountain in an array of earthy greens — blew me away. (Another bonus: When you mess up, it's easy to pull everything out and start again.)

"Being able to see that progress quickly really helps with stress," Oxford said. "The world is so frustrating right now. Having that little thing that you have control over — where you can finish something beautiful that is also useful — I think that's a real draw."

For me, holding something concrete has been a welcome antidote to days spent staring at screens, doom-scrolling and Zooming. I haven't quite figured out how to finish my rugs, but the growing stack of pseudo-completed projects in a corner of my office soothes me in a way that inbox zero never could.

"If you're working on something you're really interested in and excited about, the rest of the world can fall away, at least for a little bit," Oxford said.

— J.B.

Amy Oxford's new book, Punch Needle Rug Hooking: Your Complete Resource to Learn & Love the Craft, will be published on November 17 and is available for preorder at amyoxford.com.

Into the Wild

Embracing the insanity and indulging baser impulses

If I leave my window open at night, I can sometimes hear the eldritch yowling of several neighborhood cats either mauling each other or screwing their brains out — it's impossible to tell which. These shenanigans usually take place between the hours of midnight and 3 a.m., when I would much rather be unconscious. But one of the least convenient manifestations of my sky-high existential dread is insomnia, which reliably rears its head around that time.

So I lie awake and listen to the feline fracas, and I think about the precariousness of civilization. Sigmund Freud argued that large-scale human cooperation depends on the transformation of our basest impulses — the urge to shriek uncontrollably or to eat lots of cake while naked — into more useful, socially acceptable activities: the production of hieroglyphics, competitive bowling.

But 2020 has placed an impossible strain on the delicate psychic mechanisms that help us channel our deranged whims into good, or at least neutral, acts. Increasingly, I have found myself unable to differentiate between stress-relieving behaviors and neurotic compulsions.

Of course, there is a difference: In the universe of absolute value, deep breathing is probably superior to alcohol, and calling my friends back is definitely better than not calling my friends back. But in the universe where it's 2020, or at least in my corner of it, the benefits of any particular coping strategy have become fungible. The suckage might plateau for a day, and I will scrape by on deep breathing, but then Ruth Bader Ginsburg dies, and it's alcohol all the way.

I've always been skeptical of wellness culture, which rests on the premise that your inner world can be cultivated and managed like a garden; that existential misery is a port where the slow, unwieldy cargo ship of your soul should not dock for too long. I have the privilege of dawdling in misery in a way that many others do not: I don't have children; I have a job that pays the bills; I can afford to lie awake for hours in the dead of night, plying my insomnia with various ineffectual cures, and the only person who will suffer the consequences the next day is me.

The conventional wisdom about insomnia is that you should do something other than try to sleep. One night, while the cats outside were screaming their heads off, I somehow ended up reading the entire Wikipedia entry on D.B. Cooper, the pseudonym of an unidentified man who, in 1971, hijacked a plane for a $200,000 ransom, then jumped out somewhere between Seattle and Reno, Nev., with a parachute and a briefcase. Neither his body nor the money has ever been found. This stuff is batshit and not a good prelude to sleep; around 6 a.m., I gave up and made coffee and felt awful for the rest of the day.

The world feels insane, and every day seems out of joint in a way that makes it hard to respond to normal cues. I used to be reasonably productive during normal business hours; recently, I've become a vampire. One day, I found the sunlight so annoying and hostile in its obliviousness to the situation on Earth that I closed the blinds in my room and pretended it was night. For a few hours, I managed to trick myself into feeling liberated from the diurnal rhythms of capitalism, and in my sanctuary of darkness, I felt a little better.

In the best of times, I am an incorrigible cuticle picker; over the last few months, I have peeled enough skin from my thumbs to line the bottom of a hamster cage. Is this deranged? Absolutely. Is it free and legal and harmless to the general public? Also absolutely.

Running is probably my only "healthy" outlet, but sometimes even that feels like a terrible exertion. Last Monday, I went to my usual running haunt in the Intervale and managed to go less than half a mile before I felt an overwhelming tightness in my chest. I had the urge to lie facedown in the middle of the trail, so without giving it a second thought, I did.

The dirt was damp and smelled faintly, though not unpleasantly, fecal; a small regiment of ants marched past my nose, going about their unfathomable day. It occurred to me that someone might walk by and be alarmed at the sight of a jogger lying spread-eagle on the ground, but then again, lying spread-eagle on the ground does not seem like an unreasonable response to the year 2020. Eventually, I got up and kept running.

— C.E.

The Right Stuff

De-stressing your home

I've been working from home for more than six months, and I officially hate my overhead lights. On cloudy days or in the evening, I turn on lamps, light candles or even click on the stove light, all to avoid using the overhead lighting. I'm not sure when or how it became so grating, but after months of spending more time in my apartment than ever before, I'm noticing problems I didn't know existed pre-pandemic.

Though many Vermonters have returned to in-person work, and essential workers never left it, the initial March lockdown is still likely to have changed our relationships to our homes. And, whether our living spaces are houses, apartments or even dorm rooms, they can have a huge impact on other parts of our lives, according to Deb Fleischman, a Montpelier-based professional organizer, productivity consultant and motivational speaker.

"I believe that people's physical space is part and parcel of their psychological space," Fleischman said. "If you have a physical space that you feel comfortable in, that you feel is organized well and has an aesthetic component and serves different needs in your life, it creates the foundation for your well-being."

Through her business A Clear Space, Fleischman preaches the power of decluttering to ensure that our living spaces reduce stress rather than add to it.

"Stuff isn't just the physicality of the items," she said. "It actually translates into something bigger, which is work. It takes work to manage all your stuff."

She recommends starting with papers — you know, that pile of mail, bills, schoolwork, receipts, kids' art projects and magazines you keep saying you'll read. (Just me?) A stack of paperwork floating around without a home can be an overwhelming reminder of obligations and demands on your time. A filing system helps — along with a reality check, which is likely to tell you that you don't need most of it.

"Most people only need one drawer, one little drawer, for their family," Fleischman said. "I come to houses, and they have big giant filing systems, and most people don't even know what's in them."

If you're really afraid to throw papers out, one option is to scan documents and plop them into a folder on your computer. Digital real estate, after all, is cheaper and more plentiful than its real-world counterpart.

Creating an efficient and harmonious home isn't just about getting rid of stuff. Adding some life via houseplants can also make a big difference. Studies have suggested that plants offer their owners psychological benefits, decreasing depression and boosting concentration and creativity. Simply put, "It's nice to have some friends around," in the words of Vermont gardening guru Charlie Nardozzi.

But how do you keep your new friends from dying on you? Nardozzi, who's an author and TV and radio host, advised that the most important step in houseplant rearing is picking a plant. Think about where you'll put it, how much light that spot gets and how often you think you'll remember to water.

Succulents may be widely considered a beginner-friendly houseplant, but they need a lot of sunlight to thrive. If you're stuck without a south-facing window, there are low-light plants that will be happier in your home. Do you have pets? Some plants are toxic, so do your research if you think your cat might decide to take a nibble.

Nardozzi recommends starting with a plant that's considered practically foolproof. The snake plant — also known as mother-in-law's tongue — and the ZZ plant are two good options. He said both are "plants you can kind of put in a corner ... and water it once in a while when you remember to, and it'll be fine."

You don't have to spend a lot of money, either. One of the great joys of raising plants is realizing that leaves or stalks cut off and propagated can turn into new plants. If you have plant-loving friends, ask them to share a cutting. For those based in or near Burlington, the Facebook group BTV Plant Share and Swap hosts plant trades and giveaways, along with plenty of helpful advice.

Everyone's home priorities will be different, but Fleischman suggested it's never too early to take simple steps. Fall, like spring, is a prime time to clear stuff out or make over a home, she noted. Small changes now could make a big difference as we face down an uncertain winter.

And me? I'm embracing the small part of my soul that never left the college dorm and buying string lights to drape around my living room. Life is too short to live in bad lighting.

— M.G.

Power Lunch

Finding comfort in food without using it to escape feelings

Lizzy Pope, associate professor of nutrition and dietetics at the University of Vermont, recognizes that food provokes stress in many people even in the best of times — and these are not the best of times.

She knows because she's been there.

"A lot of dieticians have shitty relationships with food, honestly," the Barre native acknowledged. Pope, 37, said she's spent the past decade "rehabbing" her own approach to eating while figuring out how to help others build healthy relationships with food.

"Often that means giving them permission to just eat without a lot of rules and guidelines," Pope said. "When you realize you can have ice cream whenever you want, then it loses power over you."

She believes in the intuitive eating approach, which begins with rejecting the dieting mentality. Pope also advocates for health-at-every-size principles, which include respect for body diversity and the belief that health is possible for multiple body shapes and sizes.

Pope spoke with Seven Days about what Beyoncé can teach us, how to avoid (over)eating your feelings, and her grandmother's mac and cheese.

SEVEN DAYS: You often employ Beyoncé songs as teaching tools. Can you think of one that would work for the topic of stress and eating?

LIZZY POPE: I use "Drunk in Love" to illustrate that our decision making is sometimes subpar when we are drunk and when we are in love. [Just like when we are under stress], those are difficult states for us to make rational decisions [in], and so we end up on the kitchen floor thinking, How the hell did this happen?

SD: Is turning to food in times of stress always a bad thing?

LP: No, it's definitely not. Food does bring us pleasure, right? Sometimes having a pick-me-up from food is welcome and the best coping mechanism we have available.

A lot of our good memories are probably associated with food, too. You remember, Oh, when I make these cookies, it's usually because I'm with my family. I can't be with my family right now, but I'll make these cookies. To evoke those type of safe feelings seems relatively positive, especially when the world is so chaotic around us. Turning to food for a moment of joy can be beneficial.

SD: "Stress eating" has a negative connotation, but "comfort food" does not necessarily carry the same baggage. Is it a slippery slope from comfort food to stress eating?

LP: They are on a continuum. In the Intuitive Eating book by Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch, their continuum starts with sensory gratification, where you're emotional and you want a little bit of a happy feeling. Then [comes] eating for comfort — with comfort food, perhaps — and then eating for distraction [when] everything's too much, or [you're] too stressed, or maybe you're bored. [Then there's] eating yourself into a stupor. If you continue eating large quantities of food, you're basically punishing yourself for feeling your feelings.

Most people are probably in the sensory gratification, emotional eating or comfort eating, maybe distraction phases. I think when it takes a turn to the negative is when it's your only coping mechanism. Food can only do so much.

SD: If people find they are developing unhealthy eating habits due to stress, what might you recommend?

LP: There are different types of health. We focus so much on physical health, not remembering that there's mental health, emotional health, spiritual health. You're actually more likely to [engage in] emotional or stress eating because you're not taking care of your mental and emotional health.

It's about figuring out what's really behind the emotional eating. Are you bored? Are you truly stressed? Are you worried about the COVID situation, the political situation, the racial unrest?

Are there other ways you could handle your feelings? Could you journal? Could you talk to a friend? Could you talk to a therapist? Can you just sit with the feelings?

With chronic stress, sometimes I'll find myself just eating to fill the space. Is there a way you could distract yourself or change your situation? Go for a walk or just change rooms in your house, learn a TikTok dance.

SD: What's a comfort food for you?

LP: Peanut butter sandwiches. That's literally what my mom packed me for lunch every single day of my school career. I don't eat it every day for lunch anymore, but I could.

And the mac and cheese my grandma used to make at Christmas: It's the most ridiculous recipe — literally only American cheese — and it is so good.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

— M.P.

Learn more about health-at-every-size principles at haescommunity.com and intuitive eating at intuitiveeating.org.

Past Is Prologue

Learning from history and seeing the big picture

Plenty of life experiences led Bhuttu Mathews into the field of psychotherapy, but he cites the Great Recession as a key impetus. The economic stressors and sky-high unemployment of 2008 caused the number of homeless individuals and families to tick upward, as did levels of alcoholism and drug abuse. A 2014 study in the British Journal of Psychiatry suggested that the recession led to 10,000 suicides in Europe, the U.S. and Canada.

Mathews personally dealt with substance abuse and homelessness during the Great Recession, and he saw "a lot of really shady places" purporting to offer help to vulnerable people, he recalled in an interview with Seven Days.

"The great deficit then was the availability of widespread mental health services," Mathews said. "We did not have a collective capacity then, and while it's better now, we still don't have a collective capacity as it should be."

Mathews is now a public safety officer at Saint Michael's College and a prelicensed clinical psychologist with a Burlington-based private practice. He thinks the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent economic fallout could affect collective mental health in similar ways to the recession. That might sound bleak, but Mathews suggests those past experiences can give us a leg up in our current troubles.

"There's a lot of collective wisdom to be learned from generations before us, and we often lose that in our day-to-day hustle and bustle," he said.

Of course, many stress-causing factors are out of our control and were before the pandemic. Mathews cites childhood education, accessible and affordable housing, health care access, and social equity as structural issues that affect our mental health when they're lacking. For people of marginalized identities, including people of color, queer people and immigrants, discrimination and oppression compound those issues.

"There's so much of identity-based counseling that depends on ... waiting for a better day," Mathews said. However, "the resilience of marginalized communities is extremely high."

Mathews highlighted a few key concepts that are useful for framing the stress that Americans are currently experiencing. One is secondhand trauma.

Often associated with first responders or counselors, who may witness trauma without directly experiencing it, secondhand trauma can affect those exposed to disturbing images or stories. Mathews said that hearing about the suffering in the world during the pandemic could produce secondhand trauma that changes our outlook for the rest of our lives. As we adjust to wearing masks and become more wary of crowded spaces, our minds may transform along with our behavior.

"You can imagine how our thoughts are changing and our mindsets are changing and our fears are becoming much more pronounced," Mathews said.

People who have remained relatively healthy and economically stable during the pandemic may also experience survivor's guilt, or the phenomenon of regret about avoiding harm that affected others. In a time of nationwide suffering, these people may feel they have no right to be as distressed or anxious as they are.

"The first thing we need to do in terms of survivor's guilt is be OK with the fact that we deserve to be healthy," Mathews said.

Like many other social justice-oriented care providers, Mathews uses the "social model" to understand health, including disability and mental illness. In this view, a disease such as anxiety is not a moral failing — a refusal to "buck up" and power through a tough period in history — but a product of a person's environment.

"We stigmatize getting a disease very morally. We absolutely need to get out of that mindset," he said.

Ultimately, Mathews believes, understanding mental illness and its historical causes can help us survive our current stressors. "It seems like we are in a tough place, because we've never been through something like this before in our lives," he said. "But [generations] before us have gotten through just as big, if not bigger, issues."

We can draw on collective wisdom, he said, by acting as a team and working through problems with the people around us. Have others look at your problems, he suggested, who can offer "compassionate, loving suggestions" — and then do that same work for others.

"Those of us who've been through journeys like homelessness and addiction, we understand that it's easy to get into a hell, so to speak. We can get there on our own," Mathews said. "But it's with the help of others that we get out of it. We are not going to be able to get out of this working individually, in a pull-your-own-self-up-by-your-bootstraps kind of a mentality. We can only do this as a community."

— M.G.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Health + Fitness, Stress, anxiety, 2020, wellness

About The Authors

Jordan Barry

Bio:

Jordan Barry is a food writer at Seven Days. She holds a master’s degree in food studies and previously produced podcasts about bread and beverages.

Jordan Barry is a food writer at Seven Days. She holds a master’s degree in food studies and previously produced podcasts about bread and beverages.

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Chelsea Edgar

Bio:

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Margaret Grayson

Bio:

Margaret Grayson was a staff writer at Seven Days 2019-21. She now freelances for the paper, covering the art, books, memes and weird hobbies of Vermonters. In her spare time she dabbles as a pottery student, country music radio DJ and enthusiastic roaster of root vegetables.

Margaret Grayson was a staff writer at Seven Days 2019-21. She now freelances for the paper, covering the art, books, memes and weird hobbies of Vermonters. In her spare time she dabbles as a pottery student, country music radio DJ and enthusiastic roaster of root vegetables.

Elisa Järnefelt

Bio:

Elisa Järnefelt is an illustrator and writer who lives in the Champlain Valley with her husband, daughter and senior dog. She enjoys learning the names of backyard birds, planting "one more thing" in her garden, creating comics and designing new illustrated products for her small business, As Little Cooking as Possible. See them at aslittlecookingaspossible.com

Elisa Järnefelt is an illustrator and writer who lives in the Champlain Valley with her husband, daughter and senior dog. She enjoys learning the names of backyard birds, planting "one more thing" in her garden, creating comics and designing new illustrated products for her small business, As Little Cooking as Possible. See them at aslittlecookingaspossible.com

Melissa Pasanen

Bio:

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Latest in Category

Speaking of...

-

How Neurofeedback Can Help Troubled Couples Get Back on the Same Wavelength

Feb 7, 2024 -

A New Peer Support Network Hopes to Help Vermont Farmers Deal With Stress

Apr 12, 2023 -

Kimberly Quinn Overcame a Dark and Turbulent Past to Become Champlain College’s Wizard of Wellness

Oct 6, 2021 -

All Inn the Family: Three Sisters Have Transformed Craftsbury Farmhouse

Aug 31, 2021 -

How Can Parents Ease Kids' COVID-19 Anxieties About Returning to School?

Aug 24, 2021 - More »

find, follow, fan us: