Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Housing Crisis

'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted…

-

City

Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's…

-

Environment

An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval…

- Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State 0

- High School Snowboarder's Nonprofit Pitch Wins Her Free Tuition at UVM True 802 0

- From the Deputy Publisher: Winooski, My Town? From the Publisher 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Vermont Authors: How I Got My Agent

Published December 23, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 30, 2015 at 9:18 a.m.

If you're an aspiring author, you may have heard that it's almost impossible to get trade published without having "insider connections." Available evidence suggests otherwise. In an online survey of 257 published authors, posted this month on her blog, YA writer Megan Crewe found that "44.8% of the total respondents sold their first novel via an agent they had no prior contact with to an editor they had no prior contact with." In other words, they cold-queried — with success.

Sixty-eight percent of the authors Crewe surveyed had a literary agent — suggesting that making that particular connection is a vital step on the road to publication. To find out how that happened, and happens, Seven Days surveyed five Vermont writers who represent a diversity of genres and career stages. While these writers weren't regulars at Manhattan book launches, they did keep their eyes open for opportunities to network with publishing pros.

If you're seeking an agent yourself, be sure to explore the wealth of information available online, including examples of recent successful query letters. (Standards and expectations change.) Plenty of agents have blogs, and they are not shy about telling the world what they like and don't. (In particular, check out the acerbic, ever-helpful advice of Janet Reid.)

Another tip the pros often offer: Don't self-publish your book and then seek an agent to sell it to trade publishers. Yes, self-publication recently worked in spectacular fashion for John and Jennifer Churchman of Essex, whose book Sweet Pea & Friends: The SheepOver sparked agent interest and then a publisher bidding war. But they had the world's cutest sheep on their side — and a significant Facebook following. Most of us just have our words.

Alison Bechdel

Cartoonist/author of multiple Dykes to Watch Out For collections, Fun Home (basis of the Tony-winning musical) and Are You My Mother?

I didn't have an agent for many years. When I started publishing in 1986, it was with a small feminist press that didn't offer advances. In those days, almost all gay books were published by small presses, and sold in gay and women's bookstores — a relatively tiny market. But 15 years later, the landscape was different. Gay books had started going mainstream, thanks to independent presses like the one that had been publishing my work — and, as a result, those independent presses were failing. It was time for me to go out into the big wide world, and that meant finding an agent.

But by that point I'd published 10 books already and was a known quantity, unlike many first-time writers seeking agents. Finding someone to represent me was a fairly straightforward process. I wrote to several friends asking about their agents. One of them recommended her agent, and put in a word for me. Then I had a phone call with that agent. I felt pretty overwhelmed by that conversation — I was not used to thinking about things like price points, paperback versus hardcover, or how to get my books into chain stores. Chain stores at that point seemed to me like the devil incarnate.

In fact — although this seems absurd to me now — I felt like the very act of getting an agent was a form of selling out. After my years of toiling in the subculture, I had a very outsider mindset. I didn't make a decision about the agent until several months later, after going to the city and meeting with her in person. At the end of that meeting my head was still spinning, but she looked me in the eye and said she'd really like to work with me. And I was sold.

Pat Esden

Author of various published short stories and the forthcoming A Hold on Me (February 2016), the first in a paranormal romance series from Kensington Books

My path to signing with an agent wasn't easy or quick. Right from the start, when I e-queried, entered online contests or pitched agents at conferences, I received requests to submit my material. Many agents asked to see future manuscripts. But no one offered to represent me. Seven years and five manuscripts into this process, I was beyond frustrated. Finally, an in-person pitch with an agent confirmed what I'd begun to suspect. Though my manuscripts were well written, they fell into an oversaturated corner of the market, making established agents with larger client lists hesitant to take me on.

But I didn't give up. I wrote another manuscript. Within a short time, I had that manuscript out with eight agents. It often takes up to six months for agents to respond to requested material, so I decided to enter an online contest, to approach several unfamiliar agents and keep my mind occupied.

On the first day of the contest, I posted a 60-word pitch. Immediately, I received interest from an agent at a well-respected agency who was just starting to build her client list. The agent requested 50 pages. Two hours later, she asked for the full manuscript. Less than 24 hours later, she offered representation via email, a pretty amazing experience after years of querying.

Overall, what I learned from my experience is that, while prominent agents are excellent choices, don't rule out newer agents at good agencies. It's not just writing skills and a superb manuscript that hook an agent. It also has to do with the market, the agent's available time to nurture new writers, and what sort of manuscripts their current clients are working on. New agents can be a golden opportunity.

My agent is Pooja Menon at Kimberley Cameron & Associates in the San Francisco area.

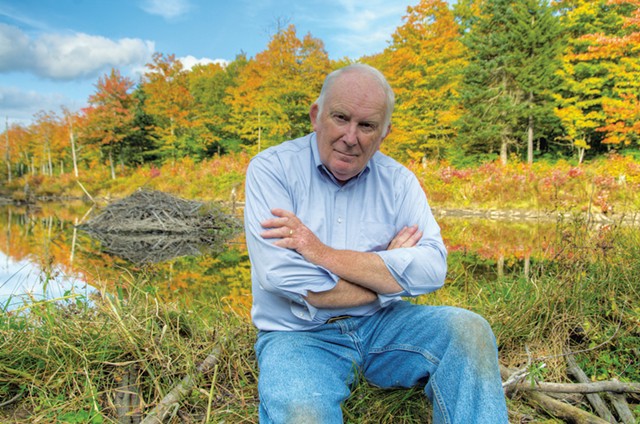

Howard Frank Mosher

Author of two nonfiction books and 11 novels set in Vermont, including God's Kingdom, published in October

About 20 years ago, after a long and renowned career, my then literary agent was planning to retire. He had helped me launch my writing career in the 1970s, and he wasn't going to be easy to replace. The better-known agents I was interested in seemed to want to steer me toward the kind of commercial fiction — thrillers, catchy contemporary issues — that I couldn't have written even if I'd wanted to.

Then I heard back from Dan Mandel, a brilliant young agent with a strong interest in literary fiction. From the start, Dan became my "first and best" editor, urging me to write what I wanted to write, what "felt right" to me. He helped me find the heart of my Lewis and Clark novel, The True Account — in which there is not one true word — and my baseball novel, Waiting for Teddy Williams. He wasn't put off by my interest in magical realism but helped me see how, in that regard, less could be more.

Book by book, Dan helped me continue to find and sustain my voice, to take the long view, and to match my stories with the right publishers. Every novelist I know has dozens of horror stories. Sometimes, in the writing life, there are also miracles. For me, signing on with Dan Mandel was a miracle.

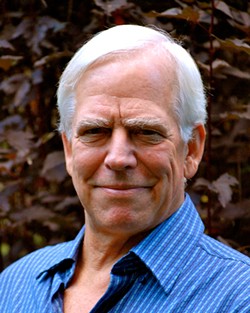

Don Bredes

Author of six novels, including three Hector Bellevance mysteries set in Vermont, and the young-adult fantasy Polly and the One and Only World (2014)

In 1972, after teaching high school English in the Northeast Kingdom for three years, I decided it was time for me to find out whether I had what it took to be a writer. So I drove west to enroll in the MFA in Fiction program at the University of California, Irvine. There, although I ended up spending as much time on the tennis court as at my desk, my short fiction impressed the program's director, Oakley Hall, enough for him to recommend me to his own agent at the time, Don Congdon, then with the Harold Matson Company.

As it happened, both Oakley and Don were capable doubles players, and so it was on the tennis court — one time while Don was out west visiting Oakley — that he offered to represent me. I was surprised — and reluctant. Don was a top-flight agent whose clients included William Manchester, Ray Bradbury and William Styron, but even so, I wasn't sure I should accept, partly because Don told me he wanted me to write a novel. I told him I thought I was learning more about crafting fiction by writing short stories.

He said, "All right, then, just write three chapters and an outline, and I'll see what I can do with that." One of my workshop stories, about a teenager's fumbling, first-time attempt at sex, seemed to lend itself to a longer treatment. That story became the second chapter. I wrote two more chapters and a 10-page outline and sent it to New York. In a few months Don sold my first novel, Hard Feelings, to Atheneum. A year later he sold the movie rights to a Hollywood producer and the softcover rights to Bantam Book. I was off and running.

Dayna Lorentz

Author of the middle-grade series Dogs of the Drowned City and the young-adult trilogy No Safety in Numbers

My agent story is unusual. It begins where my wanting to be a writer began: my love of reading. Our wonderful local booksellers invite the likes of Norton Juster, Laurie Halse Anderson and Kate DiCamillo to read for small groups of excited fans. One time, I went to such an event at the Flying Pig Bookstore that featured middle-grade author Rebecca Stead.

Before things got going, Rebecca was just standing there, and so I started talking to her. It turned out we had a ton in common outside of writing. I told her I had just gotten an offer on a manuscript but was still negotiating the contract, on my own, without representation. Rebecca generously offered to assist me in contacting her agent, who just happened to be at the top of my query list.

On Rebecca's invitation — and, let me be clear, Do not mention someone's name in a query without their offering first! — I sent her agent a version of my already highly polished query letter, added a mention of our conversation, and included sample pages of my manuscript. Her agent is now also my agent. I am so grateful for Rebecca's kindness in making that introduction, and feel so lucky to have my spectacular agent, Faye Bender, in my corner.

There's no getting around the basic work: You must revise until you have a killer manuscript, write a rockin' query letter, and research a list of dream agents. But there's also value in engaging with the writing community around you. Not only will it make the writing life less lonely, building professional relationships might open up unexpected opportunities.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Agent X"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Books, The Winter Reading Issue, Vermont authors, publishing, agents, Alison Bechdel, Pat Esden, Howard Frank Mosher, Don Bredes, Dayna Lorentz

More By This Author

About The Author

Margot Harrison

Bio:

Margot Harrison is the Associate Editor at Seven Days; she coordinates literary and film coverage. In 2005, she won the John D. Donoghue award for arts criticism from the Vermont Press Association.

Margot Harrison is the Associate Editor at Seven Days; she coordinates literary and film coverage. In 2005, she won the John D. Donoghue award for arts criticism from the Vermont Press Association.

Speaking of...

-

Hancock's Whiskey Tit Press Publishes Books No One Else Will

Dec 20, 2023 -

The Latest Issue of '05401' Honors the Architects, Idols and Thinkers Who Shaped Its Eclectic Publisher

Nov 22, 2023 -

Cartoonist Alison Bechdel Headlines the Green Mountain Book Festival

Sep 27, 2023 -

The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, March 29-April 4

Mar 27, 2023 -

Town Hall Theater and Middlebury College Performers Collaborate on 'Fun Home'

Jan 25, 2023 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Shaina Taub's 'Suffs' Earns Six Tony Nominations, Including Best Musical Performing Arts

- 2. Student Film Documents Failed Plan to Cut Books From Vermont State University Libraries Film

- 3. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, May 1-7 Magnificent 7

- 4. Bianca Stone Named New Vermont Poet Laureate Poetry

- 5. STRUT! Fashion Show Returns After Four-Year Hiatus Culture

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Adam Tendler and the VSO to Premiere Vermont Composer Nico Muhly’s First Piano Concerto Performing Arts

- 1. How a Vergennes Boatbuilder Is Saving an Endangered Tradition — and Got a Credit in the New 'Shōgun' Culture

- 2. Video: The Champlain Valley Quilt Guild Prepares for Its Biennial Quilt Show Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Waitsfield’s Shaina Taub Arrives on Broadway, Starring in Her Own Musical, ‘Suffs’ Theater

- 4. Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse Stuck in Vermont

- 5. Pet Project: Introducing the Winners of the 2024 Best of the Beasts Pet Photo Contest Animals

- 6. This Manchester Center Family Is a National Show Horse Powerhouse Animals

- 7. Crossing Paths: An Eclipse Crossword 2024 Solar Eclipse