Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

All Aboard? A Road Project Could Displace Train Yard, Buildings

Published December 23, 2015 at 10:00 a.m.

Perhaps the biggest concern about Burlington's controversial Champlain Parkway project is that the new route will create more traffic on congestion-prone Pine Street between Lakeside and King. Hoping to address that, the city is cooking up a second, lesser-known road plan: the Railyard Enterprise Project.

Officials say its centerpiece — a short road spur that veers off Pine south of Maple and connects it to lower Battery Street — is essential to divert traffic from a historic, low-income neighborhood. It has the potential to change a section of the waterfront that's largely remained an industrial wasteland.

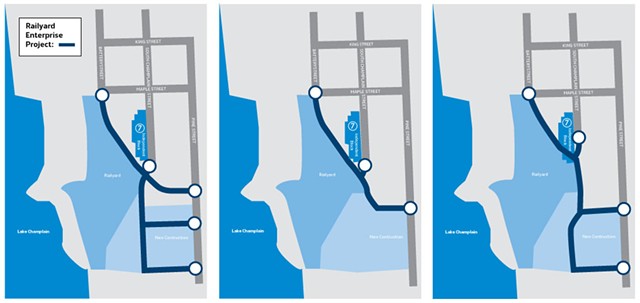

The project is creeping forward. Over the course of three years, a steering committee has winnowed down 30 different road configurations. On Monday evening, the city council signed off on the final three scenarios, all of which are en route to a federal environmental review that is expected to take at least a year.

Officials emphasize that everything is subject to change. But the current options are stoking anxiety among those who own property in the project's potential path — including private businesses and a bustling rail yard that can't easily relocate.

At a public meeting at ArtsRiot on December 9, Bob Chamberlin, a city consultant with Resource Systems Group, spelled out the conundrum: "If you avoid the buildings, you impact the rail yard. If you avoid the rail yard, you impact the buildings."

Either way, the city will also have to contend with contaminants left over from a former coal-gasification plant that once operated near the waterfront's Pine Street Barge Canal, which became a Superfund site in 1983. That designation by the Environmental Protection Agency scuttled the original route plan for the Champlain Parkway, which would have extended along the lake to Battery Street. Construction on the polluted land has the potential to unearth toxic materials.

"I think it would be fair to say this is a complex landscape to be working with," said Chapin Spencer, director of the Public Works Department.

At ArtsRiot, officials underscored that Vermont Rail System must be a "willing partner" in the project. That's because two of the options send the new road right through its rail yard at the southern end of Battery Street.

The rail yard is actually owned by the state but is leased to privately held Vermont Rail until 2054. Located a stone's throw from Lake Champlain, train cars arrive and depart at all hours, hauling all manner of industrial goods: oil, gas, lumber, road salt, gravel, cement, limestone, animal feed, heavy machinery. Nearby, a series of osculating tracks make up the switching yard, which allows trains to change course.

The railroad and government depend upon one another — Vermont Rail facilitates commerce; the Agency of Transportation helps secure federal rail-improvement grants — but the alliance hasn't always been harmonious. The company sparred with the city over the Champlain Parkway, appealing the project's Act 250 permit in 2011 over rights of way.

The relationship has had "ups and downs," acknowledged Vermont Rail's president, David Wulfson, whose father, Jay, bought the company in 1963. Currently, though, he said things are cordial between his company and the administrations of Mayor Miro Weinberger and Gov. Peter Shumlin. In 2013, he and the mayor signed a settlement over the Act 250 appeal after the city and state agreed to fix a culvert and perform "railroad diagnostics" at multiple crossings.

Despite that legal tussle, Wulfson supports the Champlain Parkway — and the Railyard Enterprise Project. His rail yard, he explained, would benefit from having a new route for trucks to enter and depart.

And it's not the first time he's imagined what it would look like. Sitting in his attic-like office at Vermont Rail's lakeside headquarters, he unfurled a diagram crowded with crosshatched lines. He had the plan drawn up in 2004 in case the city revived plans to link Pine to Battery.

Wulfson's diagram lays out how existing tracks, terminals, loading stations and storage sheds could be rearranged to make way for a street. The yard would be moved south onto land he already owns, and new tracks would be constructed — hence all the lines.

"The city has a copy of this and is aware this needs to happen," Wulfson said matter-of-factly. He's furnished the state Agency of Transportation with a copy as well. He expects government officials to pick up the tab.

Friction could occur, however, based on how closely the project adheres to Wulfson's vision and who pays for what. For the two options that require uprooting the rail yard, city planners are budgeting $6.5 million for rail yard "mitigation costs." That's in addition to the road construction expenses, which are pegged at $6.8 million or $11 million, depending on the plan. Weinberger is expecting the federal government to pay 80 percent, with the state and the city splitting the rest.

But it's unclear whether the same ratio would apply to rail-yard work.

"I think we may well face challenging issues with the rail yard," Weinberger said.

Given the millions it would cost to move the rail yard even a little bit, have planners considered relocating it, away from the lake entirely? Elsewhere on the waterfront, industrial infrastructure has been replaced with parkland and tourist attractions such as the ECHO Leahy Center for Lake Champlain.

Wulfson, whose company owns 350 miles of track, said he has scouted other locations, without success: "No one wants a rail yard in their backyard."

The mayor added: It would be "spectacularly expensive."

One of the three plans would leave the rail yard untouched, but it's complicated. Referring to a rendering of this $15 million proposal, a perplexed observer at the December 9 meeting asked, "What does it mean when the road goes through the building?"

Standing in the back, Jason Adams stayed silent, though he knew the answer all too well. His family owns the Independent Block building on South Champlain Street, which, under option No. 3, would need to be at least partially torn down. Adams, who manages the building, recently renovated the space so that Urban Moonshine can open a cocktail bar, apothecary, health clinic and herbal learning center.

Adams later said he supports the project in principle, but, not surprisingly, he's not in favor of the version that bisects his building. Dislodging his tenants would undermine the project's goal of promoting economic development, he said. Even if part of his building remained, he said any loss of already limited parking would render the place unrentable.

Adam Brooks, executive director of the South End Arts and Business Association, worries that extended construction will drive away customers from the neighborhood, warning: "There are some small businesses that could be one construction project away from closing."

The project might also displace Curtis Lumber, on Pine Street; the Chittenden Solid Waste District; a city-owned building that houses artist studios; and two buildings at the corner of Maple and Battery — home to a dive shop and, according to owner Jacob Albee, workshops for artists, musicians and "wing-nut entrepreneurs."

Peter Owens, the director of the Community & Economic Development Office, called Albee the day before this third option was unveiled. As Albee remembers, Owens told him that the road "touched" one of his properties — a whimsical building crowned with a windmill.

"Buildings don't hug," was Albee's indignant response to the euphemism.

Albee, a professional goldsmith, thinks that the city hasn't been forthcoming enough with property owners. Unlike Vermont Rail, he wasn't invited to join the steering committee. "We're told we have an equal voice, but I don't feel that way," Albee said. "There are chips on the board, and one of them has to be moved, and I'm a much smaller chip than the Vermont Railway."

Albee agrees that the King-Maple Street neighborhood deserves relief from traffic, but he said he's unconvinced the project will truly reduce congestion.

City officials insist that they've been diligently meeting with all stakeholders, including Albee. At the same time, they've got other challenges to attend to.

Some of the buildings — including Independent Block, which used to be the Champlain Valley Fruit Company — qualify as historic, potentially limiting the city's options. There are underground obstacles, too: A buried roundhouse from the original railroad and a coal-storage bin are considered significant archeological sites.

Finally, the contaminants could prove even more stubborn than the people. The pollution extends north beyond the old Barge Canal and gasification plant. In constructing the skate park and new sections of the bike path around the Moran Plant, the city had to spend more than $300,000 to dispose of a comparably tiny amount of contaminated soil.

Pointing out that other cities have successfully redeveloped polluted land, the mayor — who champions "infill" development — said he's optimistic that Burlington will be able to do the same.

Even Albee said he could still be convinced that it's a good idea. But he qualified it: "If there's going to be a road, it needs to be the right road."

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: City, Burlington, Railyard Enterprise Project, Champlain Parkway, Vermont System, Agency of Transportation, CEDO, SEABA

More By This Author

About The Author

Alicia Freese

Bio:

Alicia Freese was a Seven Days staff writer from 2014 through 2018.

Alicia Freese was a Seven Days staff writer from 2014 through 2018.

Speaking of...

-

Reinvented Deep City Brings Penny Cluse Café's Beloved Brunch Back to Burlington

Apr 30, 2024 -

Burlington’s Blue Cat Steak & Wine Bar Closes After 18 Years

Apr 30, 2024 -

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

Apr 25, 2024 -

The Café HOT. in Burlington Adds Late-Night Menu

Apr 23, 2024 -

Burlington Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s First Term Starts With Major Staffing and Spending Decisions

Apr 17, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Vermont Senate Votes Down Ed Secretary Nominee Zoie Saunders Education

- 2. Governor Makes Last-Minute Appeal to Delay Vote on Ed Secretary Nominee Education

- 3. UVM, Middlebury College Students Set Up Encampments to Protest War in Gaza News

- 4. Dog Hiking Challenge Pushes Humans to Explore Vermont With Their Pups True 802

- 5. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 6. Help Seven Days Report on Rural Vermont 7D Promo

- 7. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News