Published February 19, 2014 at 4:00 a.m. | Updated December 12, 2019 at 2:04 p.m.

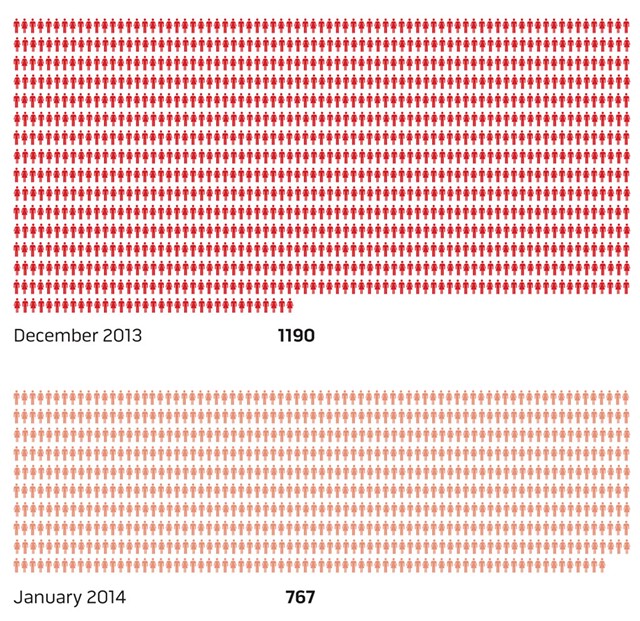

Shortly before Gov. Peter Shumlin's State of the State speech, with its unique focus on Vermont's opiate abuse problem, his health department said that nearly 1,200 addicts were stuck on waiting lists at treatment centers. That list is dramatically shorter today; officials say there are currently about 767 awaiting drug treatment, including 640 for opiate addiction.

Did the list shrink due to increased treatment resources and a political call-to-action that won Shumlin headlines across Vermont and the nation? Not exactly. While new treatment options are coming online this year, officials acknowledge that the earlier figure was significantly — if inadvertently — overstated.

Barely a week after Shumlin's speech, his Department of Health issued the lower figures and gave lawmakers a report that — in apparent contrast to the governor's call for rapidly expanded treatment resources — urged a take-it-slow approach to adding new slots.

The January report advised that, "no efforts to pursue service expansion should be pursued at this time."

Vermont Health Commissioner Harry Chen acknowledged in an interview that officials had been concerned since last fall about the reliability of the waiting list figures. Because the lists come from a wide range of community based treatment centers, they feared, total demand could be overstated.

That's exactly what was happening. After scrubbing the lists, health department officials realized that some addicts had been counted more than once, because they'd sought treatment at multiple clinics. Some had not been properly screened to confirm they either needed treatment or were eligible to receive it — say, perhaps, because they were incarcerated. Others had moved out of state.

At this point, acknowledged Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Dick Sears (D-Bennington), "We don't know what the backlog is." Nonetheless, said Sears, a key backer of Shumlin's campaign, the precise number doesn't matter as much as the clear need to get addicts on the road to recovery.

"I know we have a problem, and we have to deal with it," said Sears. "If it's 1,000 people or if it's five, that's a problem."

Nowhere was the revision in waitlist numbers more dramatic than in the state's most populous county. As recently as December 15, the Health Department said 903 people were on the waitlist for treatment at Burlington's HowardCenter, which treats severe addicts from Chittenden, Franklin, Grand Isle and Addison counties.

A week after Shumlin's speech, the department had revised the HowardCenter waitlist number to 165.

That's because the waitlist counted everyone who had called to express an interest in treatment in the past three months, said Bob Bick, director of mental health and substance abuse services at HowardCenter. Under the new criteria, an addict is only considered to be on the waitlist if he or she has contacted a treatment provider within the past 30 days, been screened by a professional and is able to begin treatment immediately.

"We had people on our waiting list who weren't screened and were currently incarcerated and wouldn't be able to come," Bick said. "The state is making more uniform what constitutes the active waitlist, and that's allowing us to understand the level of people who are eligible."

Chen said in the earlier interview that his department's message to lawmakers about the need for prudence in expanding treatment options doesn't mean there is not an unmet demand. Rather, he explained, it acknowledges that the state had already made plans to expand its treatment programs before Shumlin's speech — and can make significant progress in the near future without new initiatives.

Last year Vermont reorganized its existing and soon-to-open facilities into a "hub and spoke" model, hoping to increase capacity and improve coordination. In last few months, new methadone clinics have opened in South Burlington, Rutland and the Northeast Kingdom, creating hundreds of new treatment slots.

The bill that represents Shumlin's primary initiative includes money for more screeners and counselors, and for prosecutors to grow programs to offer addicts treatment instead of incarceration. It has progressed steadily through the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Sears, the chairman of that committee, said that while officials and journalists parse statistics on the extent of the opiate problem and treatment shortage, there is no doubt that the problems exist. "Oh, no doubt in my mind," he said. "Read any daily paper with court news."

And, even if the earlier waitlist was inflated, Chen cautioned that, for every person who seeks treatment, 10 more never come forward.

"It's good to have a better handle on exactly how many addicts are prepared to enter treatment on any given day," Shumlin said in a prepared statement. "That's the best way to monitor a waiting list, and enables us to work toward a system where everyone who wants treatment — and is prepared to start treatment — has immediate access to that support. The numbers will never be static and will certainly vary from day to day. But now we have a better sense of what our daily waiting list looks like in Vermont and what we need to do to free up space for Vermont addicts who need help."

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

'Safe Haven': Vermont Is Considering Controversial Overdose-Prevention Sites. 'Seven Days' Went to New York City to See One.

Mar 20, 2024 -

Officials Scramble to Secure Decker Towers, Burlington’s Embattled High-Rise

Mar 6, 2024 -

The Fight for Decker Towers: Drug Users and Homeless People Have Overrun a Low-Income High-Rise. Residents Are Gearing Up to Evict Them.

Feb 14, 2024 -

Lawsuit Accuses Burlington Police of Using Excessive Force on Black Teen With Disabilities

Jan 31, 2024 -

Scott Urges Lawmakers to Turn 'Catastrophe Into Opportunity'

Jan 4, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.