Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

'Safe Haven': Vermont Is Considering Controversial Overdose-Prevention Sites. 'Seven Days' Went to New York City to See One.

Published March 20, 2024 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated March 27, 2024 at 10:39 a.m.

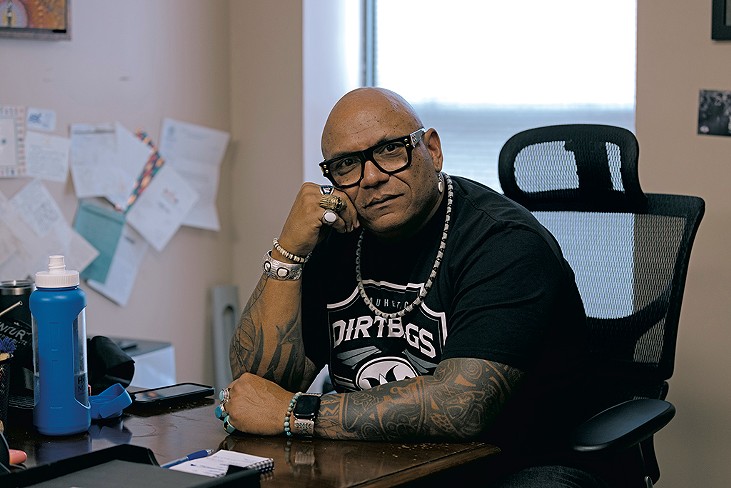

click to enlarge

- José A. Alvarado Jr.

- Jason Beltre in the supervised consumption room at OnPoint NYC in East Harlem

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

Greg Gordon never shoots up alone anymore. He knows the heroin he buys on the street in East Harlem is deadlier than ever, often mixed with fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, and xylazine, an animal tranquilizer. So when he wants to get high, as he does almost daily, Gordon goes somewhere he can use drugs among people he trusts to save him if he overdoses.

That place is an old four-story red-brick building on East 126th Street, between a cramped bodega and a litter-strewn parking lot ringed with razor wire. And those people are the staff at OnPoint NYC, a nonprofit that since 2021 has operated the only two approved overdose-prevention centers in the United States, both in New York City. Gordon can bring his drugs to inject or smoke there while a trained staff member looks on, ready to intervene if he overdoses.

On an early afternoon this month, the 52-year-old former contractor rolled his wheelchair up to a cubicle and injected opioids. Then he retired to a private room to smoke crack cocaine.

When he was finished, he packed up his drug kit, pulled a neck warmer up over his gray beard and prepared to head back out into the streets. If it weren't for OnPoint NYC, he said, that's where he'd be using, risking overdose, robbery or worse.

"This is like a safe haven," Gordon said in a soft, languid voice that showed signs of the drugs' effects. "I know they're not going to let anything bad happen to me."

Seven Days spent an afternoon at OnPoint's East Harlem location on March 7 as Vermont officials considered whether the strategy could work for the rural state. The drug epidemic has killed nearly 1,000 people in Vermont since 2019 and has made many residents feel their communities are less safe. Lawmakers in Montpelier appear likely to pass a bill in the next few weeks authorizing a pilot program with two overdose-prevention centers.

The proposal comes during an ongoing national debate about sites such as OnPoint's. Do they save lives and open the door to recovery for people addicted to drugs who are ready to quit? Or does their inherent permissiveness send the wrong message about drug use and create new public safety dangers?

Rhode Island and Minnesota have adopted plans to open overdose-prevention centers, sometimes called safe-injection sites. In December, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health endorsed the approach as "an evidence-based, life-saving tool" that is "feasible and necessary" in light of fatal overdoses.

Other states are becoming more dubious about a lenient approach to drug misuse. Three years ago, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize possession of small amounts of hard drugs. After a spike in overdose deaths and a rise in street crime, legislators there recently voted to recriminalize drug possession.

click to enlarge

- José A. Alvarado Jr.

- Greg Gordon outside OnPoint NYC in East Harlem, where he uses drugs safely

The idea of safe-injection sites in Vermont has gained traction as overdose deaths soared from 50 in 2012 to 244 in 2022.

Both leading candidates in Burlington's recent mayoral race supported locating an overdose-prevention site in the city. City Councilor Joan Shannon (D-South District), often identified as the law-and-order candidate, was initially skeptical of the approach but said that after learning more, she came to endorse it. The winner, Rep. Emma Mulvaney-Stanak (P/D-Burlington), has long backed the idea and is a sponsor of the overdose-prevention legislation that passed the Vermont House in January.

"I want Burlington to be one of the first places in Vermont that will get an OPC," the mayor-elect told Seven Days last week. She's even considering keeping her seat in the House after she is sworn in as mayor on April 1 in case her vote is needed to legalize the sites.

But support is far from unanimous. Among the opponents: Republican Gov. Phil Scott. He vetoed an opioid-response bill in 2022 because it proposed merely to study the feasibility of such sites. In his veto letter, Scott said it seemed "counterintuitive to divert resources from proven harm-reduction strategies to plan injection sites without clear data on the effectiveness of this approach." Much of the data available about such sites were from large cities and therefore "not applicable to the vast majority of Vermont," he wrote.

Health Commissioner Mark Levine told Seven Days that while such sites can be part of a broader effort that includes education, prevention and treatment, he, too, has major reservations.

"This may not be the best strategy for Vermont in terms of getting the best bang for the buck," he said on Tuesday.

Such sharply divergent views on how to address a crisis that is killing more than 200 Vermonters per year have made overdose-prevention sites one of the most politically divisive issues this legislative session. Following an emotional debate, on January 11 the House took up a bill, H.72, that would allow the sites. It passed by a decisive 96-35 vote.

The measure is now under consideration in the Senate. Advocates for overdose-prevention centers hope both chambers will be able to muster the two-thirds majority needed in the case of a gubernatorial veto.

Vermont, they say, needs places like OnPoint NYC.

A Question of Safety

click to enlarge

- José A. Alvarado Jr.

- Glass pipes with copper filters and wood pushers that are used to smoke crack cocaine

The streetscape outside OnPoint NYC can be jarring. Urban poverty and homelessness are on full display.

The people hanging around outside the center when Seven Days visited included a young man wearing a camouflage bandana over his face asking passersby if they needed anything, an apparent offer to sell drugs. An older man with a faded scorpion tattoo on his neck limped out of the center in a daze. A woman cursed a man holding a roll of toilet paper as he cleared his nose into the gutter.

"There have been shootings on that block for as long as I can remember," said Gretchen Buchenholz, founder and executive director of the Association to Benefit Children, which runs a daycare across the street from OnPoint. Cops used to stake out the bodega from the second-story bathrooms of the daycare building, she said. A needle-exchange program operated on the block for years.

When OnPoint opened in 2021, neighbors worried the center would draw more people with addictions, she said. But such concerns have largely faded.

"Our experience has been that they have been very good neighbors," Buchenholz said.

She cited a sharp drop in the number of used syringes on the street, close collaboration with the center on issues that arise and a new responsiveness of police to neighbors' concerns.

Still, not everyone is comfortable. Michael Castellano and his wife, Amanda, walked past OnPoint's building after picking up their 4-year-old son, Davy, from the daycare center. They have sympathy for people addicted to drugs but don't think the facility should be so close to a place that serves children.

"Even if the people on the inside have good intentions, there are people on the outside who have bad intentions," Michael said. Arguments break out. Profanities fly. The young parents said they just don't feel safe.

"I saw a guy whip his dick out and start peeing on a car not even 30 feet from the door," Amanda recalled. On Davy's second week of classes, a shooting put the school on lockdown, she said. The Castellanos are planning to find another preschool for their son next year.

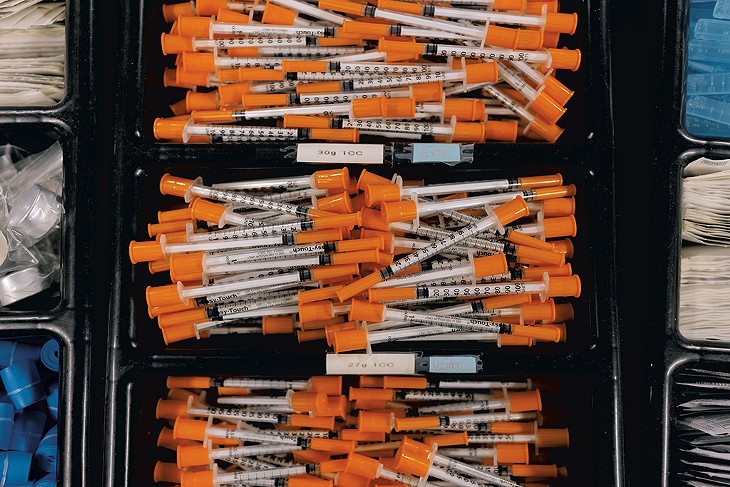

Inside OnPoint, however, staff members greet people warmly. They dispense syringes and other supplies to help people use drugs safely, inside or outside the center. The supplies are free to any adult who wants them, no questions asked.

More than a dozen clients, a mix of men and women, sat in a common room socializing, watching a gladiator movie and eating snacks. Others slumped over in their chairs or rested their heads against a wall, mouths agape. A stream of people flowed in and out of the room as new clients checked in and others left.

OnPoint also offers meals, laundry, a medical clinic, acupuncture and counseling services. The goal is to communicate clearly to clients that OnPoint is there to help — not to judge them, Sam Rivera, the group's executive director, told Seven Days.

"We're not trying to sell them something," Rivera said. "What we're doing is loving them, and then when they are here, they start to look at other opportunities for themselves."

Greg Gordon, the client Seven Days met, could use some of that love. The former electrical contractor said he got hooked on opioids around 2020, when his work dried up at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Then last year, he was robbed by a group of teenagers who pushed him off a subway platform onto the tracks in front of an oncoming train, he said, and he lost part of his left leg.

The experience haunts him. It deepened his addiction and left him, quite literally, a broken man. The memories of that day and the reality of what his life has become since, he said, are so painful that drugs are the only way he knows of to escape them.

"I'm trying to do the impossible," Gordon said. "I want to forget about something I can't forget about."

At OnPoint, he counts on doing that without risking death. Since the organization's two sites opened, more than 4,800 people have used illicit drugs in them about 130,000 times. No one has died, though there have been some close calls. Staff have administered oxygen or the overdose-reversal drug naloxone 1,450 times, which the center counts as lives saved.

"This is a health intervention that is keeping a lot of people alive," Rivera said.

Treating people as human beings with medical conditions instead of as criminals is key to reversing the nation's overdose fatalities, he said. Providing social services and a safe space can build the kind of trust that is in short supply among those who live in fear of robbery, arrest, incarceration or worse, he said.

When those with addictions are ready to choose a new path, OnPoint staff will be the people they most trust to help. In fact, staff never bring up treatment unless the client does first — which happens often, Rivera said.

"Folks who use are hearing about treatment all the time. Everybody's shoving it down their throats everywhere they go," he said. So OnPoint focuses on helping people use drugs safely. That means providing clean needles, pipes and other paraphernalia, often referred to as harm-reduction supplies.

The staff also watch over people while they use. That happens in a room that resembles a tiny, bare-bones ER. What amounts to a nurses' station is located in the center of the room, and eight mirrored cubicles line the walls. A separate smoking room similar to a sauna vents the drug fumes outdoors. A banner declares, "This Site Saves Lives" in both English and Spanish.

The mirrors let staff see if someone is starting to show signs of an overdose, such as slumping shoulders, according to Jason Beltre, a director at OnPoint. The main danger of an overdose is that it will suppress breathing and reduce the flow of oxygen to the brain, he said.

When caught early, most overdoses can be treated by stimulating parts of a person's body, administering oxygen or both. Beltre gestured to a man in a black cap in one of the cubicles who had just injected opioids and was slumping over. A staffer talked to him soothingly and pinched his shoulders. The client later received oxygen, meaning he'll be counted as someone saved.

Staff members only use naloxone in severe cases. Since they are closely monitoring the client's drug use and vital signs, they can begin by administering just one milligram of the medication, a quarter of the dose typically used on someone found unresponsive.

The smaller doses are both gentler and preferable, because a full dose can block the effects of opioids so completely that some users experience withdrawal symptoms — and immediately feel the need to use again.

"With the microdose, we're really able to stop the overdose from happening and they can continue on their journey," Beltre said.

Such trips happen more frequently than they did before the rise of fentanyl. The cheap but deadly synthetic opioid is far more powerful and addictive than heroin but also wears off more quickly, so users shoot up more often. Some people use the site more than once a day. As Rivera sees it: That increases the number of opportunities for them to ask for help.

There is a secondary reason for the mirrors: People can take a good hard look at themselves. "Part of starting to shift your life is when you start to literally see yourself," Rivera said.

Road Tripping

click to enlarge

- José A. Alvarado Jr.

- Temple Bravo, a frequent client of OnPoint NYC, organizing his drug paraphernalia and personal items

While not all of OnPoint's neighbors are happy to have an overdose-prevention center nearby, studies of these New York facilities and unsanctioned centers in the United States have found that they are not magnets for crime.

One 2023 paper, coauthored by former Burlington police chief Brandon del Pozo, now an assistant professor at Brown University, showed there had been no significant increase in violent or property crime around the OnPoint Centers in East Harlem and Washington Heights, nor an increase in 911 calls.

In fact, the study documented an 83 percent drop in low-level drug arrests near the buildings and a 75 percent drop in the broader neighborhood. Researchers suggested that may be because police intentionally avoid arrests that might deter people from using the centers.

Nevertheless, aware that concerns about crime were likely to dog the debate about H.72, three Vermont lawmakers hit the road in December to see OnPoint for themselves.

Rep. Tristan Roberts (D-Halifax), Rep. Michelle Bos-Lun (D-Westminster) and Sen. Tanya Vyhovsky (P/D-Chittenden-Central) drove to New Haven, Conn., and rode a Metro-North train to the bustling 125th Street station in Manhattan.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

Roberts was unsure what he thought about overdose-prevention centers before the trip. Would they enable people to continue using drugs, or would they help funnel people into treatment programs?

"What I saw at OnPoint was a center that really meets people where they are at," Roberts said. "People were coming in the door and getting the services they needed while being treated with dignity."

He was particularly impressed with the on-site holistic care center, where people can get acupuncture or a massage as an alternative means of managing stress.

While he's not sure such a center could work in a town like Halifax, a rural community of 800 people in southern Vermont, OnPoint struck that delicate balance between helping people continue to use safely while making alternatives available when they're ready to stop, Roberts said.

Vyhovsky, a clinical social worker, said she didn't need convincing that overdose-prevention centers work, but the trip reinforced her faith in them.

"Globally, this is not a new thing," she said, referring to the more than 200 overdose-prevention centers around the world. "We have decades and decades of evidence that it saves lives."

Before senators vote on the bill, Vyhovsky said, she's hoping to organize another trip to New York so they can see firsthand how the facilities operate. Rivera said if requested, he'd be happy to come to Vermont and talk to lawmakers in person.

A Wrenching Debate

Vermont's proposed overdose-prevention sites, as envisioned in H.72, would be smaller variations of the OnPoint model. To serve rural Vermont, one of the two pilot sites could be mobile, such as a van that would visit communities on a fixed schedule.

The bill would direct the Department of Health to adopt operational guidelines by April 1, 2025, and to issue grants to organizations that meet those guidelines.

To pay for the $2.3 million pilot program, the bill would raise the fees paid by prescription drug manufacturers on products they sell in Vermont from 1.75 percent to 2.25 percent.

Vermont has already received $13.1 million from massive national legal settlements with opioid makers such as Purdue Pharma and expects to receive multimillion payments for years to come. An advisory committee recommended using some of those proceeds to fund the pilot. To the dismay of advocates, Levine, the health commissioner, overruled the committee, saying H.72's funding stream was preferable.

Levine told Seven Days he respects advocates' position but doesn't see such sites as a "panacea" because too few communities would benefit from them.

Burlington is the only municipality he knows of whose leaders have called for one, he said. And the idea of a mobile site to serve other communities "defies logic" because users would not have regular access. Investing in existing treatment and harm-reduction programs would likely benefit more people overall, he said.

The legislation would require site operators to report the number of people who participate in the program, demographic information, the number of times overdoses are reversed, and how often emergency services or police are called. The health department would also be required to hire a researcher to study the sites' impact on crime, syringe litter and fatal overdoses, as well as whether they're helping more people get treatment.

H.72 triggered intense debate on the House floor that underscored the sharp partisan divide. Many Republicans, taking a cue from Gov. Scott, suggested that allowing people to use illegal drugs might reduce the harm to them but increase it for the community. Democrats and Progressives, meanwhile, shared emotional stories of friends, neighbors and loved ones lost to drugs.

Rep. Kate Logan (P/D-Burlington) dedicated her vote to her younger sister, Maggie, who fatally overdosed in 2006 after relapsing. Maggie suffered from mental health issues and opioid-use disorder, conditions that both carried significant stigma in her religious household growing up, Logan said.

While her sister needed lots of support she didn't get, in the end she died because she used alone, Logan told Seven Days. And she used alone because she was ashamed, she added.

On the House floor, she told her colleagues, "My parents lost one of their daughters. My children lost their aunt. And I lost my only sister. We will show those who suffer from a substance-use disorder that our community will not abandon them."

But Rep. Brian Smith (R-Derby) wondered if the bill would allow a "heroin addict" to claim he was just going to a center to get out of a drug possession charge. He said the bill was "aiding and abetting and enabling" drug users.

Rep. Art Peterson (R-Clarendon) asked whether lawmakers would bear legal or moral responsibility if someone used drugs at a site in Vermont, drove away and crashed into a carload of kids. He posed a similar hypothetical about someone who, after using at a center, walks down the street and "smashes the face of your mother, your child, your grandchild, your wife."

"You're not going to get rid of a bad habit by feeding a bad habit," he declared.

Other lawmakers peppered supporters with questions about the legality of the proposal, impacts on neighborhoods and operational details.

Rep. Joe Parsons (R-Newbury) said lawmakers had "no idea how this building is going to be run" and to pretend otherwise is "farcical."

The Senate Health and Welfare Committee begins taking testimony on the bill this week. The measure is expected to pass, but all eyes are on whether it will garner the two-thirds support needed to override a gubernatorial veto. (Advocates expect to have the House votes to override if needed.)

While Scott remains opposed, several factors suggest the case for such sites has gotten stronger since his 2022 veto. Vermont overdose deaths remain at record levels, with 214 confirmed fatalities from January through November 2023, according to preliminary health department data. Twelve additional apparent drug-related deaths are still unconfirmed. That's approaching the all-time annual high of 244 deaths, set in 2022. Levine said the lack of a sharp increase last year could reflect that deaths have "plateaued."

Vermont's overdose rate per 100,000 people rose to 38 in 2022 — one of the nation's highest.

The spike in people using — and overdosing — has taxed first responders. The Burlington Police Department answered 39 overdose calls a month last year, up from an average of six between 2015 and 2017. The Burlington Fire Department responded to 211 medical calls per month in 2023, a 13 percent increase over the prior year, driven largely by overdoses. In October, the department began dispatching a special overdose-response team in a van instead of a fully staffed fire engine.

Overdose-prevention sites aren't the only idea under consideration. Some Vermont lawmakers are keen to toughen the state's drug laws. A bill under consideration in the Senate, S.58, would increase penalties for the sale and distribution of drugs that contain fentanyl, particularly when someone dies.

Rep. Dane Whitman (D-Bennington) was initially skeptical of overdose-prevention sites. But as a member of the state's Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee, he was swayed by the testimony he read and heard about them.

"The more I heard of peer-reviewed research on the successes of sites across the world, I became convinced they achieve their intended purpose, which is to prevent overdoses and lead people to treatment and recovery," he said.

During the pandemic, Vermont followed the science about the transmission of COVID-19, and that saved lives, he said. Scott gave frequent press briefings with his health commissioner, Dr. Levine, at his side. The state also has followed other evidence-based, harm-reduction public health policies, such as drug testing and naloxone distribution.

Whitman said he's disappointed the same evidence-based approach doesn't seem to be guiding policy now.

"For whatever reason, overdose-prevention centers seemed to incite a different level of scrutiny," he said. "It touches a nerve."

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

The original print version of this article was headlined "'Safe Haven' | Vermont is considering controversial overdose-prevention sites. Seven Days went to New York City to see one."

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Kevin McCallum

Bio:

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

More By This Author

Latest in Health Care

Speaking of...

-

The Fight for Decker Towers: Drug Users and Homeless People Have Overrun a Low-Income High-Rise. Residents Are Gearing Up to Evict Them.

Feb 14, 2024 -

Backstory: The ‘Saddest Update’ on an Opioid-Addicted Source

Dec 27, 2023 -

Vermont Lawmakers May Have to Meet Growing Problems With a Shrinking Budget in 2024

Dec 20, 2023 -

Two Local Band Directors March in the Macy's Parade

Nov 22, 2023 -

New Burlington Health Clinic Will Serve People Struggling With Drugs

Nov 15, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: