Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

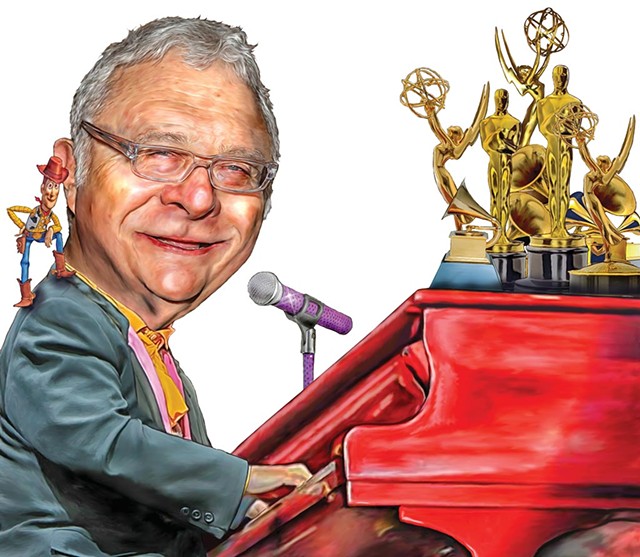

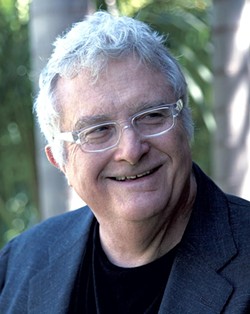

Randy Newman Talks Songwriting, Film Work and Vladimir Putin

Published June 1, 2016 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated June 3, 2016 at 9:52 a.m.

In the intro to a February 2016 profile of Randy Newman for Vanity Fair, writer David Kamp poses a fascinating question: What if rock music hadn't won? That is, what if the orchestrated stylings of Cole Porter, George and Ira Gershwin, George M. Cohan, et al., had thrived and evolved over time, instead of being surpassed in popularity by three-chord, blues-based progressions? Kamp imagines this occurring "not in opposition to rock, but alongside it."

The results might have sounded quite a bit like Newman's eponymous 1968 debut. That album combines singer-songwriter heart with dramatic sensibilities more closely aligned to the early masters of popular American song. Or, as Kamp writes, Randy Newman is "heavy on strings and light on drums," in stark contrast to the iconic guitar and backbeat-heavy pop records of the era by the likes of Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Who and the Doors. The enigmatic songwriter has always done things a little differently from everyone else.

Burlington fans will be reminded of that distinction when Newman headlines the 2016 Burlington Discover Jazz Festival this Friday, June 3, at the Flynn MainStage, performing a range of career highlights.

Now 72, Newman stands on his own singular corner of pop music. We presume it's somewhere in his native Los Angeles, where the hardscrabble avenues of folk and rock intersect with the grand boulevard of the Great American Songbook. And, as American icons go, he's sure had an odd career.

While Newman is a critical darling, widely viewed as one of pop's great songwriters, he's achieved only modest commercial success. Even that has often come in dubious ways. His biggest single is the unlikely 1977 hit "Short People," a mildly controversial tune about a disturbed man with a severe distaste for the vertically challenged. Newman's first single to crack the Billboard 200, it was treated more as a novelty than a work of high pop art.

Another of Newman's best-known tunes, the singsongy "I Love LA," has been adopted as a sort of civic-pride anthem by Los Angeles — it's even played at Dodgers home games. Never mind that it's a cynical, pointed critique of duality in the City of Angels. ("Look at that bum over there, man / He's down on his knees.") Go, Dodgers?

Still, Newman has inspired generations of folk and rock greats, who admire him precisely for the sardonic wit and mischievous style that confuse wider audiences. Elvis Costello, for one, often cites him as an influence. Countless pop artists have covered him, from Harry Nilsson to Nina Simone to Newman's idol, Ray Charles, to Pat Boone, Bette Midler and Peggy Lee.

Some have scored major hits with Newman's songs. Three Dog Night's Billboard-topping version of "Mama Told Me (Not to Come)" went gold in 1970. That band had another hit with Newman's "You Can Leave Your Hat On," which has been covered by everyone from Etta James to Tom Jones over the years.

While Newman couldn't quite pull off a mainstream merger of rock and the Songbook on his own, he has managed, more subtly, to do exactly that through others. "Mama Told Me" may be funky, but the melody harks back to the days of show tunes such as "It Ain't Necessarily So" and "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off." After all, as Mitchell Froom, who produced both volumes of the career retrospective The Randy Newman Songbook, once told journalist Michael Hill, "Randy comes from a lineage of Gershwin, not Woody Guthrie."

Newman is the nephew of Alfred Newman, the musical director of 20th Century Fox from 1940 to 1960. "Uncle Al" composed the fanfare that has opened each of the film giant's flicks since 1933. Newman's uncles Emil and Lionel were also well-regarded composers and conductors, as are three of his cousins.

Much of Newman's childhood, then, was spent with a front-row seat to old Hollywood, in studios watching his uncles conduct some of the finest film orchestras in the world. It's little wonder that the music stuck with him, or that he's won two Academy Awards for film composition himself.

Newman has become the go-to songwriter for Pixar Animation Studios, composing and writing for wildly successful family franchises such as Toy Story and Cars. That work has given his career yet another strange twist. A generation of listeners now knows Newman not as the six-time Grammy-winning Rock and Roll Hall of Famer who wrote "Louisiana 1927," "Sail Away" and "I Think It's Going to Rain Today," but from an animated toy cowboy singing "You've Got a Friend in Me."

And, if you asked Newman, he'd probably tell you that suits him just fine.

In advance of his Burlington show, Seven Days spoke with Newman by phone about songwriting, his film work, his unusual career arc and why he never listens to his own records.

SEVEN DAYS: So, this is a question I've wanted to ask you for, like, 20 years: What is your beef with short people, Randy?

RANDY NEWMAN: [Laughs] I don't have any beef with short people. I needed another up song for the album, and that one suggested itself. It's clear, and it was always clear to me, that the guy in the song is nuts. There's nobody who has that kind of mania, that anti-short-person mania. It never occurred to me that people would take it seriously. It was nothing but a joke.

SD: I was being a little bit facetious. But, as a short person myself, it's been kind of an anthem.

RN: Well, I'm sorry if it did cause some people trouble. At the time, I thought, A kid in junior high, people are always noticing them. But it seemed it wouldn't be a problem, because people would know that it was meant as a joke.

SD: I think the problem for me was more just being short.

RN: Yeah. You know, the controversy wasn't that big a deal. Or maybe it was, actually. A number of people made a lot of noise.

SD: Well, here we are still talking about it however many decades later. So it made an impact.

RN: Yeah, that's very true. I'd rather have made just nice, quiet money. If I'd had a hit, I'd rather it had been "I Love You Just the Way You Are" or something. But that's all right.

SD: You arrived at a transitional period for popular American music, when tastes were moving away from the classic American Songbook and toward rock and roll. In some ways, that was a rejection of the music you grew up on and that your family was partly responsible for. And yet you've managed to exist almost in between those styles, making music that moves singer-songwriter stuff toward more orchestrated music. How have you been able to strike that balance?

RN: It's partly because that's the family business, in a way. Three of my uncles and three of my cousins were film composers. So it was something that I saw. And if someone were to ask me when I was a kid what I wanted to do, eventually I would have said that, if I said anything at all.

They had high standards, you know. Uncle Al was head of music at 20th Century Fox, and the best guys were around at the time: Johnny Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, Alex North. And I saw all that. So I studied music — not hard enough, but I can write for orchestra. And I take the movie work just as seriously, even though what I'm known for, and what I will be known for, will be the songs, probably. But the movies are just as important to me.

And I know the repertory, the pre-1954 songs, just as Carole King knows it and [Paul] McCartney knows it. A number of people do know it, and that's of great value. It's funny how, in 1954 — you can almost date it — all the stuff arrangers and writers knew about harmony went out the window. It was just down to six chords. That's amazing to me.

SD: You never really had breakout stardom. If you had come along 20 years earlier, or maybe 20 years later, do you think the arc of your career might have been different?

RN: Oh, yeah. I would never have been an artist in the '40s. I might have been a songwriter, maybe. But maybe just a movie guy. But it would have been radically different. I was very fortunate that that happened. Singer-songwriter just wasn't a thing before the '60s.

SD: Some artists now are making similar music to what you and guys like Harry Nilsson were doing in the '60s, melding the singer-songwriter with the aesthetics of more orchestrated popular song. For example, I can't listen to Father John Misty and not think of your music.

RN: Thank you. He's very good.

SD: His stuff is a little more ... maybe debauched? But I don't think he exists if not for you.

RN: Maybe. He's perhaps a little more cynical, in a way.

SD: You rarely write autobiographically or confessionally. You're almost always a step or two removed from the characters in your songs. I wonder if that has led to some of the misunderstanding or misinterpretation of your music?

RN: Absolutely, because it's an unusual use of the form. People don't do it. I've said a number of times that songwriters ought to have the same latitude as short-story writers, where it doesn't have to be some kind of personal or confessional thing. I was always more interested in the less-than-heroic mode. In so many songs, in one way or another, the singer is the hero of the piece ... [For instance,] his heart is broken all over the place, and it's noisy. No matter what it is, it interests me less than writing about people who are a little off in some way. And that's not the norm.

SD: So part of the issue is that listeners are more conditioned to expect confessional, heart-on-sleeve songwriting?

RN: And for good reason. The people who have always liked me best are the people who do songwriting for a living. Singer-songwriters and people in the music business have always been big fans of mine, or more so, unfortunately, than the public has been. I wanted that, you know? And sometimes you get what you want.

SD: The term "songwriter's songwriter" is affixed to you more than to anyone else I can think of.

RN: I'm proud to have it. You want people you admire to like what you do.

SD: You have a new solo album that is due out this summer, correct?

RN: No. It probably won't be out until next year, because I'm doing a couple of movies and won't be able to go on the road with it or do anything for it. So I'll finish it this year, certainly. Then I'll do Cars 3 and Toy Story 4, so for a couple of years I'll be busy.

SD: In the meantime, can you tell me a little about the record? I understand you have a song about Vladimir Putin.

RN: Yeah, I do. [Sings] "Puttin' his pants on one leg at a time / He's just like a regular fella? / He ain't nuthin' like a regular fella." And it goes on. I hope he likes it.

SD: Is there a line about him riding on horseback shirtless?

RN: Yeah. "When he takes his shirt off, he drives the ladies crazy / When he takes his shirt off, he makes me wanna be a lady."

SD: [Laughs] Nicely done.

RN: "Crazy" and "lady." Now that's something they wouldn't do before 1954. And they're probably right.

SD: It's not a natural rhyme.

RN: It's a natural rhyme, but not a good one.

SD: Fair distinction. You also wrote about the conflict between science and religious fundamentalism. What can you tell me about that song?

RN: Well, it's about eight minutes long. And it's about a guy who is in an arena, and he says, "We're gonna decide here, tonight, about important matters, like dark matter and global warming." And on the one side he's got the true believers, the Presbyterians, Episcopalians, the Quakers, Shakers, bakers, you know? And on the other side are the scientists. So, he has a debate, sort of, that goes on.

It's good. It's funny. And it's long, but it doesn't seem to me like it's too long. And I'm not my biggest fan.

SD: Are you critical of your own work?

RN: Yeah, very. I never used to listen to it once I did it. But now it's so easy. You dial up Spotify, and there it is. So I find that I'm listening to myself more than I ever did in my life. Which is still not a lot. When I made a record, I would never listen to it again.

SD: Now that you are listening to some of them again, what do you think?

RN: What I think mostly is that I've been the same. I've been consistent. My last two albums, if they're not the best, they're very close to it. I don't think I've slipped, particularly. Though that's hard to say. And I'm proud of that, because it's not always the case in pop music. People give their best work before they're 30. But I don't think I have.

SD: Do you think that's because you've had so many other projects besides just your own music? Maybe that keeps you fresh in your own writing?

RN: I think so. I think you're right. Doing pictures, you have to push yourself to use more than five chords. You've got to be something other than just a songwriter. And I think that kept me sharp, to some extent. Also, not having any big success that I had to follow up. The fact that it's been fairly steady the whole time has helped.

And I've been left alone. Record companies now don't leave anybody alone, I don't think. But I was always able to do what I wanted to do. No one ever told me anything, and I'm very grateful for that.

SD: When you're writing on an assignment, how much do you have to adapt yourself to the project?

RN: Well, "You've Got a Friend" is not a song that I would have written on my own, unless I were a used-car salesman or something. But I can do that. If you tell me to write a song about a monkey who falls in love with a goat, I could do it. And I'm proud that I could do it. It's not like I'm selling out or anything. I can write to an assignment, and it's the thing I'm most confident that I'm able to do well.

SD: More confident than when you're writing for yourself?

RN: Oh, yeah. Because I'm pulling my songs out of the air, and assignments have definite parameters. And I've done them to my own satisfaction a number of times. I've done that with my own songs, too. But I never think I'll write another one when I write one. I'm better about that than I used to be, but still I'm not great.

With an assignment, you've got a deadline; you vaguely know what it's going to be about. In Toy Story, they wanted to emphasize the friendship of Woody and Andy, the kid. So, "You've got a friend, you've got a friend, you've got a friend in me." I do it reasonably quickly, and I'm generally satisfied with it.

SD: Your music has been covered by countless artists over the years. Do you have any favorites?

RN: Harry Nilsson did a good job. Dusty Springfield and Cilla Black did a song called "I've Been Wrong Before" years ago. That was a good record. I think George Martin produced it.

I recorded with Barbra Streisand in the early '70s. I played piano, and she did a couple of my songs. And I didn't think it was any good. I didn't think she had any feel for rock and roll. Singing with a backbeat is something some people can do and some people can't. But recently she put it out [Release Me, 2012]. And it's good! I mean, she's got that unbelievable voice, of course. But it's way better than I thought it was. Maybe she rerecorded it or something. But it's a very good recording of "I Think It's Going to Rain Today."

SD: That kid might go places.

RN: You know, I think she might.

The original print version of this article was headlined "The Offbeat Goes On"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Performing Arts, Music, Randy Newman, songwriting, Vladimir Putin, Video

More By This Author

About The Author

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is Seven Days' assistant arts editor and also edits What's Good, the annual city guide to Burlington. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Speaking of...

-

Rain Curtails Historic 'Sound of Music' Concerts

Jun 22, 2024 -

Two Local Band Directors March in the Macy's Parade

Nov 22, 2023 -

Before a Burlington Show, the Wood Brothers Get Back to Basics

Oct 26, 2023 -

After a Half-Century of Leading Local Ensembles, Steven and Kathy Light Prepare a Musical Farewell

May 3, 2023 -

Double E 2023 Summer Concert Series Kicks Off With the Wailers

Mar 17, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Video: Plainfield Recovers From Catastrophic Flood Stuck in Vermont

- 2. Vermont’s Olympic Rowers Head to Paris Outdoors & Recreation

- 3. Vermont's Singular Sculpture on the Highway Project Gets a Facelift Art Review

- 4. Vermont Comedy Club Chef Mo AlDoukhi Cracks Eggs and Jokes Grilling the Chef

- 5. The Magnificent 7: Must See, Must Do, July 24-30 Magnificent 7

- 6. Visiting Randolph, Vermont? What to See, Do and Eat on Your Trip Visiting Vemont

- 7. Newly Formed Montpelier Performing Arts Hub to Purchase Gary Library Performing Arts

- 1. Three to Six Hours in Newport, Vermont’s North Coast Culture

- 2. Burlington’s Semipro Soccer Team, Vermont Green FC, Is Winning On and Off the Field Outdoors & Recreation

- 3. Québec’s Powwow Season, a Summer Tradition, Kicks Off Québec Guide

- 4. Vermont’s Olympic Rowers Head to Paris Outdoors & Recreation

- 5. Theater Review: 'The Beauty Queen of Leenane,' Dorset Theatre Festival Theater

- 6. Vermont Playwright and Musician Stephen Goldberg Dies Performing Arts

- 7. State Architectural Historian Devin Colman Steps Down — and Into a New Role Architecture