Published August 19, 2015 at 10:00 a.m.

A cocaine addict stops smoking crack and attends counseling sessions. As a reward, his drug-treatment counselor gives him gift certificates to local stores. A patient who's obese, sedentary and at high risk for a heart attack starts exercising and eating right because his cardiologist gives him a free gym membership. A pregnant heroin addict stops shooting up in exchange for payment of her utility bills.

Drug addictions, eating disorders and other high-risk behaviors rarely have simple solutions. But Stephen Higgins knows that even small material incentives can make a huge difference when they're offered in conjunction with proper counseling and medical supervision. And he has years of scientific data, including independent research from around the world, to prove it.

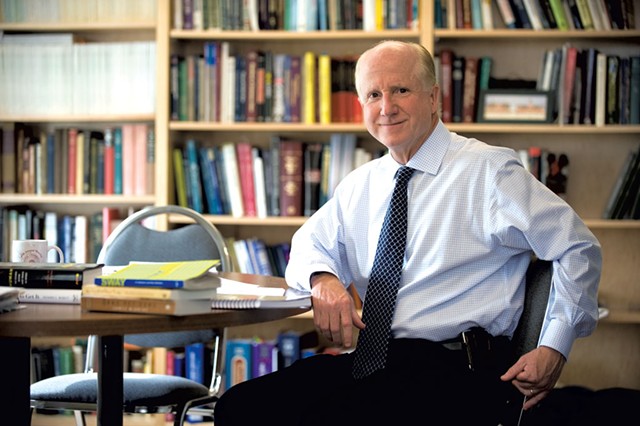

Higgins is a professor and vice chair of the University of Vermont's department of psychiatry and director of the Vermont Center on Behavior and Health. An expert on human behavior and addiction, he's spent the past 30 years at UVM studying cocaine, opioid and tobacco dependencies, especially among economically disadvantaged populations.

Higgins is credited with pioneering an addiction-therapy method known as "contingency management," wherein patients earn financial or material rewards for abstaining from drugs. Those incentives, which patients tailor to their unique needs, steadily increase in value over time but remain contingent on passing routine drug tests. If a patient fails a urinalysis, the "carrots" disappear, and the patient starts over from square one.

Developed at UVM during its landmark cocaine studies of the 1980s and early '90s, Higgins' method was later used successfully to treat heroin addicts and pregnant smokers. Today, the VCBH, which was established in 2013, is researching the method's use to combat other major causes of chronic disease and premature death, including obesity and patient noncompliance with medical instructions.

The fundamental principles underlying Higgins' research have found applications beyond the field of chemical dependency, too, in the realms of epidemiology, health care reform and criminal justice. Yet, so far, they haven't trickled down in a significant way to the day-to-day treatment of addicts outside an academic setting.

The method has proved so effective that the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have awarded VCBH $34.7 million in grants to expand its research into other areas of public health, making Higgins one of the university's biggest grant recipients. Just last month, he landed a five-year, $3.6 million grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Its goal is to help 250 low-income mothers quit smoking and thus reduce their young kids' exposure to secondhand smoke.

Why the focus on patients from lower income brackets? A facile explanation would be that Higgins, 61, grew up in a working-class neighborhood of Philadelphia — he was the first in his family to attend college. But, while Higgins did witness the consequences of heroin addiction during his inner-city upbringing, he says his current interest in the links between poverty and poor lifestyle choices isn't motivated by personal factors, just stats.

Long ago, Higgins and his fellow researchers observed that the success rate of patients trying to overcome addictions closely correlates to their socioeconomic status. Though the physiology of chemical dependency doesn't distinguish between rich and poor, researchers know that many bad lifestyle options — smoking, drug use, unhealthy diet, lack of exercise — cluster in lower economic strata.

Higgins wondered: What's driving such differences? And why do certain socioeconomic groups respond better to behavioral interventions than others?

Clearly, he notes now, education and family upbringing play important roles. But Higgins identified other common behavioral threads among patients who were economically disadvantaged. Patients of modest means, be they cocaine users or cardiac patients recovering from bypass surgery, are more likely to focus on the present and discount the importance of the future. As a consequence, options that are more desirable in the short-term rather than the long-term can unduly influence their decision making.

Such tendencies are by no means unique to addicts or the poor, Higgins emphasizes. All of us make similar decisions every day, consciously and unconsciously, as we compare different commodities and weigh their relative worth: Should we eat a kale salad or a slice of pizza for lunch? While the former is good for our hearts and won't make us gain weight, the other is tasty, cheaper and delivered right to our door.

How does the human fondness for instant gratification dictate the use of incentives in treating drug addiction? Higgins explains that most of us have "naturalistic" incentives to make healthy choices. All humans are physiologically capable of becoming addicts, yet most people don't, because they don't want to lose their jobs, go to jail or ruin relationships with family.

To those who do become addicts, all those naturalistic incentives may seem "probabilistic" — that is to say, the dire consequences seem less likely to occur, at least in the short-term. And people who are economically disadvantaged may find it difficult to think and plan for five years in the future when they don't know where they'll be in five months, or even five weeks.

During the cocaine studies, Higgins discovered that every time patients produced a clean urinalysis and earned another reward, they became more "invested" in the changed behavior. The instant gratification they got from each new reward actually triggered the same pleasure centers in their brains as the substances they had been using.

Once the incentives go away, however, do the healthy behaviors endure?

"That's the big question," Higgins says. "I had shown with cocaine [treatment] that, if you pair it with counseling around lifestyle changes, the incentives can produce changes that are sustained for several years."

After the cocaine studies, Higgins took on the problem of smoking among pregnant mothers, which is known to produce lower birth weight and other complications. Researchers had been studying possible interventions to get expectant moms to stop using tobacco since the 1980s. When Higgins implemented the incentives program with a group of such women, he produced a 35 percent success rate, compared with a 7 percent rate in his control group — a five-fold improvement. Similar studies under way in Scotland and Australia are producing comparable results.

"Thus far," he says, "everyone has been successful."

Could similar incentives help low-income cardiac patients stick to healthy regimens? Higgins' colleague at VCBH, Diann Gaalema, is now collaborating on a study of the use of contingency management among such patients with Dr. Phil Ades, a pioneer in cardiac rehabilitation at the UVM College of Medicine. As Higgins explains, patients from lower-income backgrounds tend to have both more complicated medical histories and lower participation rates in cardiac rehab.

"You could provide them with the best pharmacology or the best technology for stents," he says. "But if you can't get your patients to take their medicines or quit smoking, it can undermine everything."

That's a serious problem, Higgins notes, because the evidence says that when patients don't do rehab, their odds of dying or being rehospitalized within the next few years increase dramatically. Gaalema and Ades want to see whether incentives can increase participation rates among lower-income patients. Thus far, Higgins says, the data look "really promising."

Yet another VCBH study focuses on weight gain among obese pregnant women. The Institute of Medicine recommends that obese women gain very little weight during their pregnancies, yet "that's easier said than done," Higgins says, "especially among a population that tends to gain weight."

The study provides expectant mothers with incentives to stay within specific weight parameters, along with nutrition counseling. Higgins says those results have been encouraging so far, too.

In the decades since contingency management was developed at UVM, it's been adopted in other settings beyond the world of drug treatment. Years ago, Higgins notes, his research helped lay the foundation for the nation's first drug courts — treatment-focused alternative-justice programs for nonviolent offenders. When the cocaine studies began, he says, drug courts didn't exist. By the time the studies concluded in the 1990s, there were about 2,000 such courts nationwide, including in Vermont. "I think that's one of the great outcomes of our work," Higgins says.

Contingency management has also been used in Africa by the International Monetary Fund to persuade fieldworkers to visit health clinics for HIV testing. In the United States, many corporate employee-wellness programs have adopted the method to get workers to do timely medical screenings such as mammograms and colonoscopies.

Alan Budney, a professor of psychiatry at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, studied under Higgins in the early '90s and worked on the initial cocaine studies. He calls Higgins "a bigwig" in the world of addiction research and contingency management. Today, Budney uses similar incentives to help teen drug users overcome their dependencies.

Budney's wife, Catherine Stanger, an associate professor of psychiatry at the Geisel School, uses similar incentives to get kids with type 1 diabetes to monitor their glucose levels. According to Budney, "These incentive systems work better than anything anyone else has tried."

As part of a research study, Spectrum Youth & Family Services in Burlington has treated its adolescent addicts using contingency management protocols developed by Budney and Stanger. But Annie Ramniceanu, who was Spectrum's clinical director for many years before accepting her current position at the Vermont Department of Corrections, points out that most therapists aren't trained in proper use of incentives. Moreover, many don't "know or believe in it and its efficacy."

One possible reason: Vermont does not have a master's degree program in substance abuse counseling. And other advanced degree programs in counseling typically have only one course on substance-use treatment, and contingency management may not be taught or emphasized, Ramniceanu says.

Indeed, Budney says that Higgins' work on contingency management has probably had a greater impact outside the world of drug treatment than within it. Why?

"The substance-use world is a tough nut to crack," Budney says. Lack of funds conspires with inertia to obstruct change in this domain of low-paid providers. "New programs that cost more money aren't that fathomable for people working in the field," Budney says. "And there's no reimbursement code for incentive-based treatment in the Medicaid system."

For his part, Higgins prefers to focus on the positive. Contingency management, he says, has had a tremendous impact in the unlikeliest of places.

"We never could have anticipated that," he says. "When the world of ideas takes over, you never know where it's going to go."

To find out more about contingency management and other research, visit uvm.edu.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Big Payoffs"

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Lt. Gov. Zuckerman Goes on a 'Banned Books Tour'

Sep 6, 2023 -

UVM Hillel Provides Shabbat Meal Kits With Student-Grown Vegetables

Aug 29, 2023 -

Centerpoint, Which Educates and Counsels Hundreds of Teens, Is Poised to Close

Jul 5, 2023 -

Heather Moore, New Executive Director of Shelburne Craft School, Is Learning on the Job

Aug 31, 2022 -

Vermont Officials Release Relaxed COVID-19 Guidance for the School Year

Aug 24, 2022 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.