Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Are Vermont State Colleges Still Fulfilling Their Mission?

Published September 3, 2014 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 8, 2020 at 5:17 p.m.

click to enlarge

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- CCV Montpelier associate dean of enrollment Pam Chisholm (left) with CCV Montpelier president Joyce Judy

Summer-separated friends run across lawns with outstretched arms. Skateboarders zip along the sidewalks that crisscross the green. The campus of Johnson State College is so lush and the sunshine so vivid on a late August morning that even the first-year students appear more excited than anxious.

You'd never know "an imperfect storm" is brewing, as Castleton State College president Dave Wolk describes the challenges facing Johnson and the entire Vermont State College system. Diminished funding and dropping enrollment numbers are making it increasingly difficult for Vermont's consortium of colleges to fulfill its mission: to educate and train Green Mountain residents so they can find work and pay taxes without leaving the state.

Largely because of the price tag, the Vermont State College system — Johnson, Castleton and Lyndon state colleges, Vermont Technical College and the 12-campus Community College of Vermont — educates more than twice as many Vermonters as does the University of Vermont. Last fall, UVM had 2,966 full-time, in-state undergraduates; in the same semester, the state colleges enrolled more than 10,000 Vermonters, 5,921 of whom were full-time students at CCV.

Vermonters pay $9,600 a year to attend Johnson State; multiply that by four, and the total is still less than a single year's tuition at an elite private school such as Stanford or Harvard. In-state tuition at UVM is $14,184; out-of-staters, who account for nearly 68 percent of UVM's student body, pay $35,832.

"Johnson's fairly inexpensive, so that was my main reason for coming here," says Seth Chornyak, a sophomore from Richmond, who was having lunch in the cafeteria with Miranda Bergin and Ashley Morrissette. Chornyak, a photojournalism major, said his older brother went to George Washington University and "racked up a lot of debt in his first couple of years." He reasoned, "I thought I'd save money by going to a state school."

Price is the object in the Vermont State College system, which the state legislature has charged to provide affordable higher education to Vermonters. Yet that same legislature's funding for the VSC has diminished precipitously over the last several decades. In 1980, state funding accounted for half of VSC's revenues; now it's 18 percent. Vermont consistently ranks at or near the bottom of the list in state appropriations for public colleges.

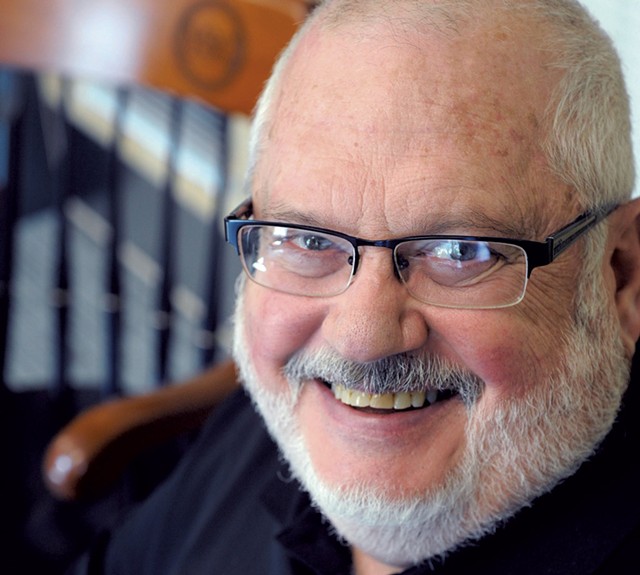

"The way we fund public, post-secondary education is the least progressive thing in the state," says Vermont Tech interim president Dan Smith.

In May, Gov. Peter Shumlin signed a law that aims to restore the 50-50 funding ratio of yesteryear. But until that law's provisions take effect — and there are no official deadlines — the VSC's constituent schools will effectively be treading water at a moment when more and more Americans are questioning whether a college education is even worth it.

Meanwhile, enrollment at VSC schools is trending downward system-wide: In 2013, 436 fewer students enrolled than in 2008.

Says State Sen. Ginny Lyons (D-Chittenden), a sponsor of the bill and part-time professor at CCV's Williston campus: "If we underfund these institutions, we're pulling the rug out from under our future."

History 101

The Vermont State College system was created by a 1961 legislative act that decreed it would be "supported in whole or in substantial part with state funds." But with the exception of CCV, its constituent colleges have longer histories. Castleton State, initially chartered as a grammar school in 1787, was a girls' seminary for much of the 19th century, and in 1867 became a teaching college. Johnson and Lyndon, founded in 1828 and 1911, respectively, also served to train educators. Vermont Technical College was founded in 1866 as the Vermont Agricultural and Technical Institute.

The consortium's 1962 creation was part of one of the most important educational movements in American history: the establishment of state-funded colleges that aimed to make affordable post-secondary education available to previously underserved populations. New York's SUNY system predates Vermont's by 14 years. The University System of New Hampshire started in 1963.

The affiliation among VSC colleges was relatively loose until the late 1970s, when the organization's board of trustees — nine gubernatorial appointees, one student representative and five state legislators — began strengthening ties. In the centralized model adopted in 1977, the board took on oversight of all of VSC's financial, academic and personnel matters, which would be administered by the office of the chancellor.

In the early 2000s, leaner budgets changed things. The chancellor's office still carries out certain administrative functions for all VSC schools — payroll, institutional research and so on — but in the new millennium, the individual colleges have greater autonomy. Each school individually recruits students, hires faculty, receives accreditation and administers its academic programs. Outgoing chancellor Tim Donovan refers to his office in its current state as a "holding company."

At the same time, the VSC began to encourage greater collaboration. A key example: The schools share a common course-numbering system, which allows for what Donovan calls "a free flow of credits" among them.

Although each of the five schools keeps its own tuition revenue, it simply receives one-fifth of the overall legislative appropriation for state colleges, and administers those monies as it sees fit.

That means CCV, with 12 campuses, gets the same appropriation as 1,500-student Lyndon State, which occupies a single, rural campus. "You can make the case that it's illogical, but in some regards it's as logical as anything," Donovan says. He adds that the even division has eliminated all the "game-playing" around budgeting. And, he notes, "We're down to a level of money that, in some regards, is not worth fighting over."

Niche Programs

Though each state college tends to attract students from its own region of Vermont, they all draw from the same statewide applicant pool, making some amount of variation in identity an economic necessity.

All five VSC schools are career oriented, but Vermont Tech is uniquely hands-on. At its central campus in Randolph and its expanding campus in Williston, the school offers majors in such fields as engineering technology, dental hygiene and agriculture.

Although Vermont Tech offers online courses in several fields, CCV is the real trailblazer in online education. The school offered its first online course in 1996, when mailboxes were still crammed with CD-ROMs for AOL's newfangled internet service.

According to CCV president Joyce Judy, approximately 250 of CCV's 1,000 fall 2014 classes are online only, a figure she calls "significant and growing." For Judy, the commitment to online courses is simply an extension of CCV's overall mission, which, as she puts it, "has always been about access ... How do we help more Vermonters access college?"

CCV also distinguishes itself by eschewing the traditional residential model and by employing only part-time faculty — to ensure instructors are "practitioners," as Judy calls them. Shawn Kerivan, who teaches "pretty much every writing course the college offers" at its Morrisville location, is also a journalist and an innkeeper. That real-world experience, he says, "gives the faculty who teach there a lot of credibility to be in the community, doing what we're teaching."

The other three schools in the VSC system are all liberal arts colleges with comparable enrollments and wide-ranging course offerings. As such, they've taken a finer-grained approach to differentiating themselves.

Castleton State, the largest of the three, offers popular majors in such fields as nursing and sports administration, and has established itself as a player in public opinion research with its Castleton Polling Institute. It is also the only VSC school to field an NCAA Division III football team.

Johnson State has largely cast its lot with the arts, developing programs in writing, performing arts and music; the school also recently renovated its performing arts center. Programs of study in business, public relations and teaching licensure also attract many majors.

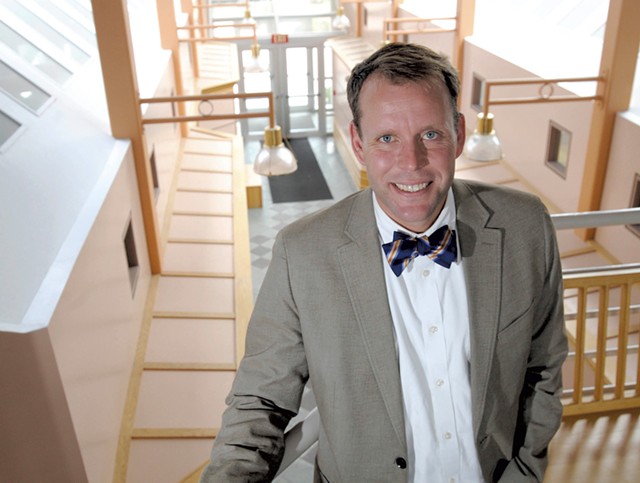

Joe Bertolino, the president of Lyndon State College, says that approximately 80 percent of the school's students major in one of six "niche programs": mountain recreation management, music business and industry, exercise science, an applied visual-arts program, and its two most acclaimed courses of study: atmospheric sciences and electronic journalism arts. The school has graduated several well-known meteorologists. In August, NewsPro magazine ranked Lyndon's journalism program 10th best in the country, just below such perennial heavyweights as Syracuse and Columbia.

For Bertolino, niche specialization is more than just a way to make his school stand out in a crowded field. It's a way to cope with the steep decline in state funding. "No one is expecting additional funding from the state," he says. "It's not gonna happen ... We have no choice but to be more efficient in our practice, and to make some really tough decisions. We're not going to be all things to all people. Here are our top programs, and that's OK. That's who we are."

Adapt — or Else

"Let me give you both of my cards," says Tim Donovan in his Montpelier office, located in an unassuming building across the parking lot from Hunger Mountain Co-op. One card is for his official job, from which he'll resign on December 31. The second reads, in big, bold letters, "KEEP SMILING."

The outgoing chancellor may be an optimist, but he's also a pragmatist. He doesn't minimize VSC's challenges. His job, though, is to keep the system functioning, even in the face of cuts and surprise setbacks. For example, the legislature approved a small boost for the VSC budget in May, only to reverse it in August when a downgraded revenue projection prompted a $30 million statewide budget rescission.

Donovan has gone on record saying any further reductions would force the VSC consortium to make cuts of its own — in personnel. So far, VSC has enacted no system-wide firings, but certain schools have made smaller-scale cutbacks. Vermont Tech, for instance, recently eliminated six staff positions and elected not to hire replacements for two retiring faculty members.

In 38 years holding various positions in the VSC system, Donovan has seen it all. "The path through ... ebbs and flows in enrollment or funding or economic conditions," he says, "is constantly reinventing the things that you do to carry out your mission. That's just part of the deal. You either adapt to those things or you don't — and the alternative isn't very good."

In 2009, a legislative task force investigated consolidating two or more VSC schools, and concluded that any minimal gains in operational efficiency would be offset by losses in each school's particular culture and identity. Donovan, no fan of consolidation, also notes that because the colleges are significant revenue drivers in their respective towns and counties, the economic impacts of consolidation could be devastating.

Unlike small private schools and large state schools, the VSC system does not have a history of attracting private donations; alumni gifts constitute a small percentage of their operating budgets, and they all have small endowments. The only way to make up the deficits is to increase tuition. Castleton president Wolk says with regret that his school, for example, has found it necessary to raise the price tag every year for the last dozen years. Barbara Murphy, president of Johnson State College, says, "No one wants to raise tuitions, but it's about the only variable we have that the board can control."

Harder to control: the negative enrollment trend. In the fall of 2009, VSC students, including out-of-state ones, numbered 13,170; last year, that dropped to 12,656. Enrollment at Vermont Tech has declined about 10 percent over the last three years.

The dwindling numbers can be explained in part by a larger demographic trend: declines in state birth rates and overall population. Daniel Hurley, associate vice president for government relations and state policy at the Washington, D.C.-based American Association of State Colleges and Universities, provided an illustrative fact sheet. It shows that Vermont peaked in its production of high school graduates in academic year 2007-2008 and projects a decline of 27 percent — to about 2,500 graduates — by 2022-2023.

Hurley calls the situation in Vermont "alarming." On one hand, he notes, the demographics are dipping and state college tuition is rising; on the other, the state has a need for an increasingly skilled labor force.

"Those are huge conflicting forces that will largely determine the state's future: economically, democratically, societally," Hurley says. "It's frankly incumbent upon state political leaders of all stripes and persuasions to realize the data that is at hand, and to try to address college affordability as part of a broad, sweeping plan to boost the prospects for economic prosperity in the future."

Because They're Scrappy

"Scrappy" is the word that several VSC administrators use to characterize the system's resilience.

"We do a lot with not too much public support," says Johnson State College president Murphy, "which has made us be a very hardworking, committed system. It's an inspiring place to work."

It's also been a workplace that's put a premium on creative solutions, as administrators have had to devise system-wide programs to boost enrollment and tuition. One of these is the multipronged Dual Enrollment Program, which allows academically gifted Vermont high school students to take two tuition-free courses at any VSC school. Credits earned count toward high school graduation, as well as toward the student's college education, should he or she choose a college in the VSC system.

A program at Vermont Tech, the Vermont Academy of Science and Technology, allows talented, science-minded high school seniors to take a full year of courses, tuition-free, at that college — and essentially skip freshman year.

Other solutions to the budget and enrollment crunches have emerged at the individual colleges. In addition to Lyndon State's niche programs, Bertolino is focused on attracting more international students and, by offering evening and weekend classes, courting local "nontraditional students."

In offering several low-residency graduate programs, Castleton State has taken a page from the playbook of private Vermont colleges such as Goddard College and Vermont College of Fine Arts. Now, students can get an MA in arts administration or an MS in athletic leadership there.

Johnson State's Murphy recalls a recent "really hard decision" to shut down an underused daycare center on campus. "People understood the decision," she says, "but it was very unpopular. We are not in the business of offering childcare."

Of all the state colleges, CCV seems to be in the best position. Its tuition rates are the lowest in the system, and its endowment has doubled in the last five years, to $1.8 million. Approximately 40 percent of its graduates carry zero debt, according to associate dean of enrollment services Pam Chisholm. But CCV still pinches pennies, by such measures as using open-source courseware for online classes. More crucial to the bottom line is another policy: Of all VSC schools, CCV is the strictest about canceling courses if they do not attain a certain level of enrollment.

Public to Private?

What is the future of the VSC system? In light of flagging state support, "I think the question becomes, 'To what extent do you behave like public institutions?'" says Donovan. "One of the things we say here is that we're no longer a publicly funded institution, but we remain a publicly missioned institution. Is there a limit to one's ability to do that? Sure, but I don't know what that limit is."

Several constituent schools already collaborate with businesses. CCV, for instance, has found a willing partner in telecommunications giant Comcast, which is interested in building up a workforce of skilled college graduates. The school teaches classes for Comcast employees at the company's South Burlington facility; Comcast's tuition-benefits program assists with students' course expenses.

The mutually beneficial arrangement stops short of privatization. But Castleton president Wolk isn't afraid to use that word. "What you're seeing, not just in Vermont but especially in Vermont, is a gradual privatization of public education," he says. "This has a been a discussion at UVM for years. Is the university public or private, given [the state's] very low level of support?"

Wolk says he doesn't have the answer; neither does he suggest that his or any other VSC college should "behave" more like a private institution. Rather, he expresses a sentiment that crops up again and again in conversations with those who work in and care about Vermont's state colleges: The legislature needs to figure this out, and fast.

"It would be helpful to know [from] state policy leaders — the governor, the legislators — what does Vermont want out of its public higher-education system?" says Wolk. "Do they want one or more of us to privatize? Do they want us to try to make it on our own ... with some flexibility on tuition? Should we market our colleges more and more to out-of-state students, which is what UVM has done? Those are the questions that have evolved from this imperfect storm."

Caught in that storm are the students themselves. Miranda Bergin, one of the students dining with Seth Chornyak in the Johnson State cafeteria, has an older sister at the same school. For families who send more than one child to Johnson State, the school offers a 25 percent break on one sibling's tuition. Last year, Bergin's parents paid for some of her tuition; this year, she's covering it all herself. Splitting the tuition discount with her sister saves Bergin $600 per semester. The rest comes from a part-time job. Like Chornyak, Bergin works weekends at Best Buy in Williston.

"It's awful to think about," Bergin says, "but it kind of feels like everyone in this room is in debt until God knows when."

The original print version of this article was headlined "College Try"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Education, Back to School, college, funding, higher education, tuition

More By This Author

About The Author

Ethan de Seife

Bio:

Ethan de Seife was an arts writer at Seven Days from 2013 to 2016. He is the author of Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin, published in 2012 by Wesleyan University Press.

Ethan de Seife was an arts writer at Seven Days from 2013 to 2016. He is the author of Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin, published in 2012 by Wesleyan University Press.

Speaking of...

-

Lawmakers Support Amending Law, Delaying School Budget Votes

Feb 9, 2024 -

Vermont Colleges School Students on Wellness as Mental Health Concerns Mount

Jan 17, 2024 -

Lt. Gov. Zuckerman Goes on a 'Banned Books Tour'

Sep 6, 2023 -

UVM Hillel Provides Shabbat Meal Kits With Student-Grown Vegetables

Aug 29, 2023 -

Heather Moore, New Executive Director of Shelburne Craft School, Is Learning on the Job

Aug 31, 2022 - More »

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 2. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 3. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 4. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 5. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 6. Norwich University Names New President Education

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News