Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Essential Soldiers: Virus Response Showcases the Versatility of the Vermont National Guard

Published December 9, 2020 at 10:00 a.m.

A week after the coronavirus pandemic prompted Gov. Phil Scott to declare a state of emergency in late March, Lisa Kromer of Essex got an unexpected phone call.

The 30-year-old special education teacher had been a part-time combat medic in the Vermont Army National Guard for seven years, but she'd yet to put her skills to the test. Now she was being asked to treat patients in a makeshift field hospital should the University of Vermont Medical Center be overrun with cases of the deadly virus.

She didn't hesitate. Kromer was one of the first of the 3,200-member-strong Vermont National Guard to volunteer for active duty in the state's pandemic response. Eight months later, she's still on the front lines.

"This is probably the most important thing I've ever been called to do for the Guard," Kromer said from the Winooski COVID-19 testing site she helped manage last month.

Flying F-35 Lightning II jets is the Vermont Guard's highest-profile mission. The next-generation fighter-bombers based at Burlington International Airport are a source of intense pride for the Guard but have prompted equally intense criticism from some in Chittenden County for the deafening roar they inflict on residential areas.

But this year, the Guard's boots-on-the-ground effort to combat an invisible enemy took center stage. The part-time soldiers' multifaceted response has been on a scale not seen since the devastating floods of Tropical Storm Irene in 2011, when Guard members air-dropped supplies to inaccessible communities, moved mountains of debris, and rebuilt bridges and roads.

COVID-19 has caused a very different kind of crisis, slower moving but more devastating, touching every corner of Vermont. From the Guard, the pandemic has demanded a greater variety of skills and responses. From many of its soldiers, it has required a longer, more personally disruptive commitment to helping Vermonters meet an emergency with no predictable end date.

In March, when it appeared that hospitals might not be able to handle a surge of COVID-19 cases, Guard members built several temporary field hospitals, and the Guard's medical specialists prepared to staff them. When job losses struck and food insecurity soared, teams skilled in logistics loaded up trucks and distributed 3.2 million pounds of food around the state.

Guard members established pop-up sites where thousands of Vermonters were tested for the coronavirus. They helped the state's contact tracers call people who were potentially exposed to the virus, warning them to quarantine.

And when hackers infiltrated the UVM Health Network's computers, a sophisticated Guard geek squad, trained to combat cyberterrorism, helped the hospital system rebuild its sprawling network.

These and many other tasks — often behind the scenes — have driven home for state officials just how indispensable its army of citizen soldiers can be in times of crisis.

"From being a war-fighting force to providing really critical resources in a domestic response, their versatility really is unmatched," said Erica Bornemann, director of Vermont Emergency Management.

But the Guard is a finite force, and there are signs it may be getting stretched thin. So far, its leaders have not had to compel any part-time soldiers to serve in pandemic-related assignments. Every time a call for volunteers has gone out, enough reservists have agreed to put their civilian jobs on hold and report for duty.

Nearly nine months into the emergency, though, the number of volunteers is dwindling, raising the prospect of mandatory call-ups. Further, more than 1,000 Vermont Guard members — 950 soldiers and 85 Air National Guard members — are getting ready to deploy overseas in the coming months. That could come at a crucial time in the pandemic recovery, when the Guard's help may be needed for mass distribution of vaccines.

Guard leaders express optimism that their remaining force will be robust enough to respond to any foreseeable local need. Nearly 2,200 reservists will remain in Vermont as their fellow Guard members serve in Europe, Africa and Central Asia.

But leaders acknowledge that the pandemic's unpredictable nature — as evident in the recent spike in infections and fears that holiday travel may deepen the crisis — makes the pandemic response the Guard's greatest challenge yet.

"With Irene, you knew what you were going to rebuild," said the Guard's leader, Adj. Gen. Greg Knight. "You knew where your focus had to be. This one is different."

Not Trained in Vain

click to enlarge

- James Buck

- Guard members checking in people for COVID-19 tests at the armory in Winooski

The Guard excels at responding to domestic emergencies because its soldiers are well prepared for foreseeable threats and skilled at figuring out the unforeseeable ones, said Maj. Joe Phelan, commander of an Army Guard combat medical unit.

"One of the reasons we are so successful in these types of scenarios is because we are familiar with and train for operating in the unknown," Phelan said from the Army National Guard Armory in Winooski shortly before Thanksgiving.

The drab brick building in a quiet residential neighborhood had been transformed into a free COVID-19 testing station, one of two the Guard was operating in the state that day.

As Phelan spoke, people waited in line for the tests. Guard members wearing masks, face shields and protective blue gowns over their fatigues entered arrivals' information into laptops. Others on the team carefully inserted cotton swabs into people's noses and prepared the samples for shipment to a lab.

Since May, Task Force Coyote — two teams of about 15 members each — has operated pop-ups in 25 locations and collected more than 30,000 samples.

All team members have some medical training; the combat medical company to which most are assigned has a core wartime mission to treat ill or wounded soldiers in the field. Last year, many headed to Louisiana for training that included learning how to operate in contaminated environments, Phelan said. Such skills, including scrupulous donning of personal protective gear, have proven highly useful in their current assignment.

Nevertheless, the length of the emergency has created significant challenges, Phelan said. Many Guard members never anticipated being on the front lines of a global pandemic, which takes a personal toll.

"No, you're not getting shot at, but you are getting exposed to COVID-19 every single day," Phelan said. "This is foreign territory for all of us."

Some Guard members have found it difficult to serve because their children are attending school online, from home. Others are stressed out about the health of vulnerable family members.

"A lot of these soldiers don't want to go home at night," Phelan said. "They stay in barracks because they don't want to put their families at risk." More than a dozen soldiers are living at Camp Johnson, the Guard's Colchester headquarters, because of such concerns or because they can't easily commute.

Kromer is among them. She's been living in the barracks for months because she hasn't wanted to infect her boyfriend, a physician who lives in Essex, or drive back and forth to her mother's home in upstate New York. She's even had to leave her labradoodle, Atlas, with her mother during the pandemic.

The switch to remote learning made the special ed teacher's work with autistic teens impossible, so stepping away from her day job was not a hurdle. But other Guard members have struggled to balance their civilian jobs with their military service.

click to enlarge

- Bear Cieri

- Guard members building a medical facility at the Champlain Valley Exposition in Essex Junction

Darwin Carozza, a 22-year-old Norwich University graduate from Merrimack, N.H., said he felt conflicted about temporarily leaving his job at an investment firm in September to help with the testing effort. A commitment of one month has turned into three and a half, but his employer is supportive.

"The whole idea of the Guard is, you have these citizens who do military training and, when the time comes, we put down our pitchforks and come in from the fields and we serve the country when we need to," Carozza said. "I love that."

With roots dating back to colonial militias, the Vermont Guard is a hybrid fighting force composed of dozens of individual units. It has facilities such as armories and firing ranges in 26 communities around the state and is constructing a $27 million Army Mountain Warfare School in Jericho. The Green Mountain Boys, as the Guard members are known, conduct missions that include flying fighter jets and helicopters and fighting in mountainous terrain.

Of the Guard's 3,200-strong force, about 900 are full-time "active Guard," including high-ranking officers and Air Guard members with specialized roles, such as F-35 pilots and ground crews.

The majority are part-time reservists, so-called citizen soldiers, who commit to training one weekend a month and two weeks a year, as well as whenever they are ordered to active duty. The Pentagon might send them overseas, as it did when 1,500 Army Guard soldiers headed to Afghanistan in 2010. Or the governor can activate the Guard for domestic emergencies, such as Tropical Storm Irene.

The Guard has 700 fewer members today than when its ranks peaked at 3,900 in 2001. When campaigning for the job of adjutant general in 2019 — state legislators elect the Guard's commander — Knight stressed to lawmakers the need to improve recruitment and retention. Just last week, he and Vermont Education Secretary Dan French held an online, town hall-style event to highlight the Guard's educational opportunities.

"We'd like to have more people available," Knight told Seven Days.

With so many Guard members working in civilian jobs, recruiting volunteers can be difficult. The Guard has the authority to require that members report for duty; when it does, by law civilian employers must allow them to go and to return to the same position.

"We are getting a little bit tight in terms of how many people are able to assist on a volunteer basis without taking them away from their normal jobs," Bornemann said.

The number of reservists who volunteered for in-state assignments peaked in late April at 268, as the Guard raced to set up temporary surge sites. That number dropped over the summer to about 60 as the state experienced one of the lowest rates of infection in the nation. Since the Guard responded to the recent cyberattack on the UVM Health Network and bolstered the state's contact-tracing ranks, that number has bumped back up to 114. A total of about 400 Guard members have been called to active duty at some point during the pandemic.

That response to date has cost about $8 million, according to the Guard. The federal government picked up 100 percent of the tab through August. Since then, the state has been responsible for 25 percent of the cost but has drawn the money from its $1.25 billion federal pandemic CARES Act grant.

While the Guard has a "deep bench," Phelan, the combat medical unit commander, said keeping the pop-up test sites fully staffed has required a regular rotation of new Guard members to replace those who need to get back to their civilian lives.

A 33-year-old UVM biology major whose deployment to Afghanistan in 2010 led to a full-time job in the Guard, Phelan said he marvels at the selflessness Guard members show daily. Members of testing teams who were unable to return home spent the Thanksgiving holiday together to make the best of it.

"I admire them, and I'm grateful for them," Phelan said.

Their diverse skills were evident at the Champlain Valley Exposition grounds in Essex Junction last month. About 35 members were rebuilding a makeshift 250-bed overflow hospital after having dismantled it over the summer when it looked like it wouldn't be needed. With cases on the rise and an uncertain winter ahead, Guard members in all manner of civilian professions, from plumbers to surgeons, reassembled the structure in days.

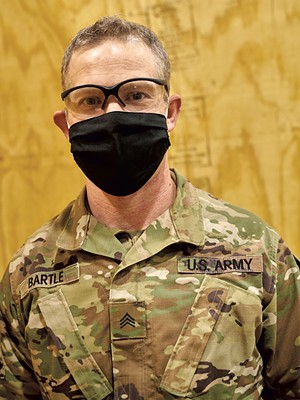

As Fred Bartle of South Hero, a software developer in civilian life, installed a junction box on a plywood wall, he said he wasn't going to waste his breath complaining about having to rebuild the facility.

"Despite how I feel about doing it again, it's just as important as the first time," Bartle said. "I'd much rather have it and not use it at all."

A 40-year-old father of two who plays the trumpet in the Guard band, Bartle is part of a team known as a quick reaction force that is ready to deploy anywhere in the state in a matter of hours. Knight refers to the team as his "Swiss Army knife" because of the wide variety of skills its members possess. They have private-sector experience in medicine, construction, trades and technology.

There's always a tension between serving one's community and one's employer, and Bartle said he feels that intensely. He goes home at night to his wife and daughters and works on software projects with looming deadlines.

"I think my boss would rather I didn't do this, but he doesn't have much choice," Bartle said.

The Cavalry

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Capt. Kyle Key

- Vermont Army National Guard Computer Network Defense Team training in Arkansas

Days after a cyberattack in late October crippled the UVM Health Network's computer systems, Al Gobeille, executive vice president of operations at UVM Medical Center, was feeling frazzled.

Gobeille, who formerly served as Gov. Scott's secretary of human services, was at the end of his third consecutive 20-hour workday, and the network's medical records system remained down. Appointments and procedures had been delayed or canceled. Thousands of computers and devices were infected with malware, and the prospects of quickly restoring the system were bleak.

"It was a rough time," Gobeille recalled. Then he got a call from a top Guard official who explained how a team trained in combating cyberterrorism might be able to help.

"To have someone call and say, 'Hey, I've got folks that I can send that can help you' — it was a pretty good moment," Gobeille said.

Some hospital officials initially expressed skepticism that the 10-member Guard unit could contribute much to the network's information technology team of more than a hundred people, Gobeille said. After learning of the unit's capabilities, however, UVM officials realized the asset they had at their disposal.

"Everyone I talked to that has never had anything to do with the Guard was like, 'They have a cyberterrorism team?'" said Gobeille, who served as a Guard ordnance officer himself decades ago.

Its members have years of training in fortifying computer networks against hackers. Just weeks before the breach, the team participated in Cyber Shield 2020, an exercise designed to sharpen their defenses against cyberattacks, said Col. Chris Evans, the Guard's IT director.

Despite this training, the team had never been called up to deal with an actual cyberattack in Vermont. "After a while, you get a little discouraged and you're saying, 'God, are we ever going to be able to go in and help out?'" Evans said.

Officials have been tight-lipped about the origin and nature of the October 28 attack, citing an ongoing Federal Bureau of Investigation probe. But the federal Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency had been warning health care organizations of an increased threat of ransomware attacks in which cybercriminals take a network hostage and demand payment. The attacks were initiated through phishing — or fake email campaigns — with links to malicious websites that, when clicked, infect and disrupt a network.

Despite "champing at the bit" to help fight the hackers, Guard members had to first fight red tape. "We didn't have building passes, so at first we couldn't even access the different facilities," Evans said. "A lot of those little things hung us up at first."

Once they were in the buildings and IT managers understood their skills, the Guard helped in myriad ways, including helping scan the network's more than 8,000 linked devices and rebuilding infected servers. Ultimately, about 5,000 devices turned out to be infected, Gobeille said.

The mission, which lasted about a month, was considered separate from the pandemic response, though it helped restore essential services at the region's largest hospital as COVID-19 cases increased. It drove home to Evans the importance of building relationships with organizations responsible for critical infrastructure before a crisis hits.

"Every exercise, every mission, makes us stronger, and this definitely falls in that category," Evans said.

Guardians of What?

Not everyone has been thrilled with the Guard's pandemic response.

Back in April, not long after most Vermonters were ordered to stay home to slow COVID-19's spread, F-35 training flights increased fivefold. Homebound Vermonters fumed.

"We live in a brick house that shakes when they go over," Richard Olmstead, who lives in Winooski, told Seven Days at the time. "I'm just infuriated by it."

James Leas of South Burlington shares those sentiments. A patent attorney, social activist and fierce critic of the F-35 program, Leas argues that the Guard ought to park the high-tech fighters and focus its energies on pressing problems, such as food distribution.

Leas said he was appalled that the Guard continued flying the deafening planes over surrounding communities as stressed Vermonters hunkered down at home. The Burlington City Council agreed and passed a resolution asking the governor to ground the jets during the pandemic.

"Let's focus their training on really doing good for the people of Vermont," Leas said. "They've shown they can do it."

The number of members taking part in the highly publicized pandemic response is modest, he noted, suggesting that the Guard has enough manpower for a more robust deployment.

Burlington City Councilor Jack Hanson (P-East District) also said he'd like to see the Guard "double down" on its pandemic response. The contrast between what he views as the wastefulness of the F-35 training flights and the beneficial work of the Guard's pandemic response is stark, he said.

"They are doing great work, but clearly the problem of Vermonters struggling during this pandemic isn't solved," Hanson said. "There is no way you can tell me that doing more of that critical work wouldn't be beneficial to our community."

Tension between the federal and state missions is nothing new. Even as U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) showered the Guard with praise for its response to Tropical Storm Irene, he called it "regrettable" that so many of the Guard's Black Hawk helicopters, which would have proven useful, were in Iraq at the time.

After Irene, the Vermont Guard had help from units in other states. That hasn't happened this time, since every part of the country is coping with the COVID-19 pandemic.

"In the time of COVID, no governor wants to give up their medical expertise, so what we have is what we have," said Lt. Col. Randy Gates, the Guard's director of military support.

However, the total number of Guard members available for domestic assignment can be misleading, Gates said: "We've got people on rosters, but that doesn't necessarily mean that they're the best match for a particular mission."

Knight advised the governor earlier this year that the Guard could still perform both its federal mission to fly the F-35s and its state mission to help with the pandemic. Scott agreed and declined to stop the flights.

The Guard's ability to fight on multiple fronts is what makes it so valuable, but its primary mission will always be to serve Vermonters, Knight said.

"We were built for this."

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: News, Vermont National Guard, pandemic, VTANG, military, pandemic response

About The Author

Kevin McCallum

Bio:

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Kevin McCallum is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse and state government. He previously was a reporter at The Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, Calif.

More By This Author

Latest in News

Speaking of...

-

National Guard to Buy Vermont State University Land for New Facility

Aug 4, 2023 -

Video: Adrian Tans Draws an Audience With Chalk Art on the Woodstock Town Smiler

May 18, 2023 -

Lawmakers Decline to Extend Vermont's Motel Housing Program

May 10, 2023 -

Video: Trent Cooper Celebrates Three Years of Trent’s Bread in Westford

Feb 23, 2023 -

Vermont Wants Evidence That Pandemic Unemployment Recipients Were Eligible

Sep 21, 2022 - More »

![] - KYM BALTHAZAR](https://media2.sevendaysvt.com/sevendaysvt/imager/u/blog/31844051/military1-1-1fd76d2122be4e3b.jpg?cb=1680219946)

find, follow, fan us: