Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Former al-Qaeda Prisoner Theo Padnos Reflects on His Ordeal

Published November 30, 2016 at 10:00 a.m.

On October 20, 2012, Theo Padnos made a risky decision that nearly killed him: He walked calmly across an olive grove in Turkey with three young men he trusted, ducked through a barbed-wire fence and disappeared into the maw of Syria's bloody civil war.

The freelance journalist from Vermont thought he was going to interview Free Syrian Army fighters who were trying to overthrow the regime of President Bashar al-Assad. Instead of getting that story, Padnos stumbled into another one when he was kidnapped, imprisoned and tortured by members of Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qaeda's Syrian affiliate, aka the Nusra Front. He spent 45 days with his hands and feet bound in a cell the size of a dog kennel and another 200 days in a heat box that he likened to "being buried alive."

Almost no one in Vermont knew Padnos was missing throughout his 22-month ordeal. There were no yellow ribbons at the Putney School, where Padnos attended high school; at Middlebury College, where he got his bachelor's degree in comparative literature; or in Woodstock, where he has lived on and off since ninth grade.

The silence was intentional, strongly advised by the U.S. government. Padnos' mom, Nancy Curtis, figured out that her son was in trouble when his emails from Turkey abruptly ceased — at the time, Padnos was guiding her on the purchase of a new woodstove. She immediately notified the Federal Bureau of Investigation, but weeks went by before an agent took her seriously.

That agent, whom neither Curtis nor Padnos will identify, urged Curtis to keep her son's abduction out of the press, because the publicity could be deadly. Like the parents of journalist James Foley, who was taken in Syria one month later — and beheaded by Islamic State militants less than a week before Padnos' release on August 24, 2014 — Curtis had joined an elite club to which no one wants to belong: the family members of American journalists kidnapped in Syria and Iraq.

A few friends were in on the secret, too. "We were really concerned, and I felt really helpless," recalled Woodstock resident Kirk Kardashian, who stayed in contact with Curtis for the duration of her son's captivity. "These things don't happen to Americans all that much. So it's weird to be in this situation where your friend just disappears."

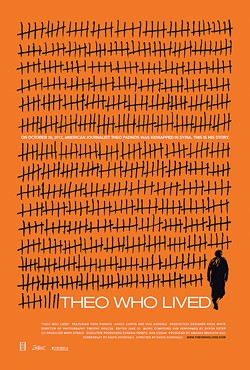

Padnos, 48, is now the subject of a newly released documentary that chronicles his abduction and captivity. He also narrates and stars in Theo Who Lived, which the New York Times called "imaginative and affecting." It notes that Padnos is, "among other things, a compelling movie character: voluble, articulate, energetic and still understandably agitated."

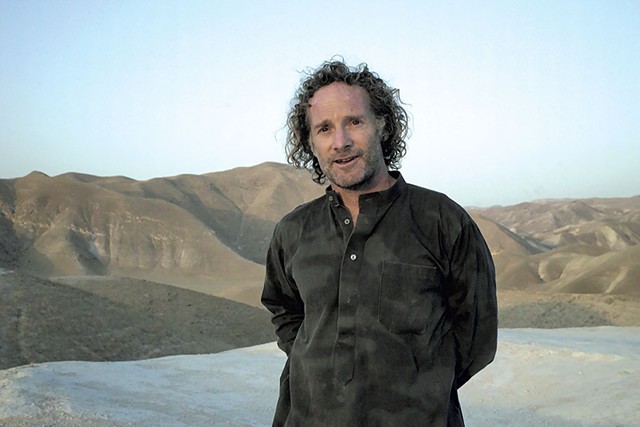

Director David Schisgall brought Padnos back to the Middle East less than a year after his release to retrace each step of his terrifying odyssey, from the streets of Antakya, Turkey, to the barbed-wire Syrian border to facsimiles of the dungeons in which he was interrogated, confined and tortured. The two met through Schisgall's wife, Effie Peretz, who attended grade school with Padnos.

Padnos spares the viewer few details of his harsh detention: the unrelenting abuse at the hands of his tormentors, some of whom were children as young as 10; his repeated escape attempts, including one during which Padnos' fellow prisoner and cellmate, American photojournalist Matthew Schrier, abandoned him at the last minute; his suicide attempts; and, finally, his trips through the Syrian desert with Abu Maria al-Qahtani, the Nusra Front leader who broke with the Islamic State and who ultimately released Padnos to United Nations workers in the Golan Heights.

To convey what it was like for those who waited for and worried about him, Schisgall interviewed Curtis and her niece, Viva Hardigg, inside the light-filled country comfort of a Vermont abode. Their anxious accounts and multiple shots of lush Vermont contrast sharply with the grim reality Padnos faced for almost two years in the Middle East.

"I had fallen into the darkness and woken in a netherworld, the kind found in myths or nightmares," Padnos wrote in a New York Times Magazine piece published a few weeks after he was released. "I knew there was a kind of logic to this place, and I could tell that my captors wanted me to learn it. But what exactly they wished to teach me, and why they couldn't say it straight out but preferred to speak through their special language of pain, I couldn't understand."

'We're That Connected'

I met Padnos for the first time in November 2003, shortly before the publication of his first book, My Life Had Stood a Loaded Gun. Named after an Emily Dickinson poem, it chronicles Padnos' experiences teaching poetry to convicted kidnappers, rapists and murderers in the now-closed Woodstock Regional Correctional Facility in southern Vermont.

Thirteen years later, as we chatted over coffee at Burlington's New Moon Café, I looked at Padnos for hints that might reveal how his own captivity had changed him. His curly, salt-and-pepper locks are thinner and grayer but otherwise recalled the same unruly mess I remembered. His face, while still angelic, sported several days of stubble, but his cheeks looked hale in contrast to the photos of him that circulated in the press immediately after his release in August 2014. One Associated Press image, taken from an undated video shot by his captors, showed Padnos sitting cross-legged on the floor, his wrists bound in his lap, a Kalashnikov rifle aimed at his head. He looked disheveled and broken, like a beaten dog.

With iPhone in hand, Padnos scrolled through his recent Facebook messages, including one he'd just received late the night before. He showed me the photo of a thirtysomething Syrian man pointing at his own bandaged chest, the way a gang leader might boast about fresh battle scars. Padnos played the attached audio file, then expertly translated the Arabic.

The speaker was Abdul Qadr, a Syrian fighter. He inquired about Padnos' health, then said he was angry with Padnos for not writing more often. The bandages, he explained, were the result of injuries he suffered in a recent air strike by either the forces of Assad or the Americans, he wasn't sure which.

"Qadr isn't officially in ISIS. He may be and might not be. I really don't know, and I don't care, either," Padnos said. "I know he gets along pretty well with the ISIS authorities, knows everyone in Jabhat al-Nusra and wants to get out."

"The FBI knows who this guy is, right?" I asked naïvely.

"Are you kidding? Of course not. Why would they know?" Padnos said dismissively. "There are thousands ... just like him. Thousands, thousands, thousands. And they all want to come to Turkey and Germany. The more we bomb them, the more they want to run away to Turkey. This guy, if he had the cash, he'd be in Berlin tomorrow."

I stared, with an air of incredulity, trying to imagine how Padnos, a resident of Woodstock, could casually sip espresso in a Burlington coffeehouse and exchange pleasantries with a Syrian jihadist who's being bombed by American fighter jets.

"War nowadays," Padnos said with a chuckle. "This is the nature of the world we're living in. We're that connected."

But Padnos paid a steep price for such connections.

One year after My Life Had Stood a Loaded Gun, he got to work on his next book, which sought to explain why young, angry and disillusioned Muslim men from Europe and the United States travel to Yemen, renounce their lives in the West and embrace jihad. He went abroad to study Arabic and Islam, eventually journeying into the Yemeni countryside to Dar al-Hadith, one of the world's most radical mosques.

"Even ... before I left for Yemen, I was aware that Americans wandering around the Arab world often wandered into trouble," Padnos wrote presciently in the resulting 2010 book, Undercover Muslim: A Journey Into Yemen.

Although Padnos doesn't disparage Islam in his book, he describes going through the motions of surrendering to the faith — and, in the eyes of al-Qaeda, a false conversion is a sin punishable by death.

As Padnos explained in Burlington, he almost immediately regretted the book's title: Whenever he'd check into a hotel in Beirut or Amman under the name Theo Padnos, the desk clerk would google his name and discover his book. Soon after its publication, he legally changed his name to the more anonymous-sounding Peter Theo Curtis, assuming he'd be safer traveling in Muslim countries.

It didn't work out that way.

Survival of the Wittiest

In Theo Who Lived, Padnos attempts to explain why he chose to enter Syria without a specific writing assignment. Penniless and dealing with related "self-esteem issues," he didn't tell a soul where he was going. Acknowledging now that it was "crazy," "stupid" and seemingly suicidal, he explained that he's always been a risk-taker. In fact, he had been a rock climber despite the fact that his mother's brother died doing it in the 1950s.

But his intellectual interest in Islam appears genuine, and the way Padnos talks about his experience in the 86-minute documentary indicates he doesn't hold anyone else personally responsible for what he suffered.

Ironically, he explained, his fluency in Arabic and deep knowledge of Islam — "all this stuff I thought was a personal strength — turned out to be a personal liability."

Shortly after he was taken, Padnos was hauled before an Islamic judge and accused of being a U.S. Central Intelligence Agency operative. The judge issued no formal decree, but Padnos believes his captors were told that they could do with him as they saw fit.

Soon thereafter, they figured out his real name. "The guy that discovered this, somehow he didn't kill me for some reason," Padnos explained. "I don't know why. He was a very sinister person who has since been killed by a drone."

In the initial months after his abduction, Padnos said he found himself in a place of "deep disorientation in time and space," unaware of who was detaining him or whether he'd live or die. More than once, his captors told him he was about to be executed.

"I was in many different prisons. Usually I would arrive in a blindfold and handcuffs in the trunk of a car. 'Get in that room! Sit down and shut up!'" he recalled them yelling. "They were beating me. Is it morning? Night? What time is it? I didn't know."

Throughout his captivity, Padnos did whatever he could to orient himself. To keep track of the time, he used a rock to scratch a calendar into the wall.

"When they discovered I had been drawing on the wall, they came in with these pieces of wood and beat the shit out of me," he recalled. "You're not supposed to know what time it is." When his captors told him he wouldn't live past November 2012, Padnos didn't bother making a December calendar.

He was a year and a half into his captivity before they allowed him the use of a pen and paper. Even before then, he had begun composing a novel in his head, partly to pass the time, Padnos explained, but also as a way to make sense of his terrifying experience.

That novel, tentatively titled The Vermont Branch Church of Scholars, Simple Ones and Free Women, is set in the fictional town of Shepherds Crossing. It's about an epidemic of violence that seizes a small Vermont community, and it centers on a young woman who works in a local prison. She develops a relationship with a backwoods cult leader who burned down the town's church. This Vermont town became Padnos' metaphor for the violent extremism gripping Syria.

"Something similar was happening in Deir ez-Zor," Padnos said about the Syrian city where he was taken. "Five years ago, if you went to this city, you couldn't pay for your tea because they were so loving and gracious to foreigners ... If you went there today, they'd cut off your head."

Padnos' novel served another function: It kept his guards entertained. He'd have conversations with them, then find ways to incorporate their dialogue into his book. And to them, the story fed into their guilty sexual obsessions with American women.

"All they wanted to know was, 'Is this story real? Is it about sex? And if it is, tell me more,'" Padnos said. "That's all they cared about."

Two's a Crowd

Padnos had company for some of the time he was imprisoned. In fact, many of his fellow inmates were Islamic State fighters who were at war with Jabhat al-Nusra. They included Qadr, Padnos' Facebook buddy, who had once been a mid-level lieutenant in the Nusra Front until, as Padnos puts it, "he saw the writing on the wall" and changed alliances.

"The distinctions that we make between ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra and the [Free Syrian Army] are not as important to them," Padnos explained. "One day they're one thing; the next day they're the next thing. They're much more fluid on the ground than our analysts believe. And when those refugees come over, they all have a past. It doesn't mean they want to continue that past."

That empathy — which Padnos also extends to his captors — does not apply to his fellow American Schrier, with whom he shared a cell for seven months.

In Theo Who Lived, Padnos explains how the duo planned to escape together. He said they worked together for days, loosening the wire mesh on the window of their cell. When push came to shove, Padnos helped Schrier out, but the freed man didn't return the favor.

Schrier offered a different account to the media when he got home, but director Schisgall didn't interview him for the documentary. Instead, he acknowledged the conflicting versions of what happened by showing Padnos watching Schrier on television — and then calling him a liar. "The still-glowing resentment Mr. Padnos has for Mr. Schrier makes for a surprising and gripping scene," the Times review observed.

"He was like the abusive husband, and I was like the cowering wife," Padnos said at New Moon. "I don't need to ever talk to this guy again."

A week before our interview, Padnos spoke to a TV news crew from Toronto. During their captivity, Padnos and Schreir were interrogated by men whose accents Padnos recognized as French-Canadian. After Schrier's escape, his stolen credit card revealed the purchase of computer equipment that was shipped to Montréal. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police are still searching for those jihadists.

"I think I'm Facebook friends with the mom of one of those guys," Padnos said.

Why does he maintain such connections?

"As a journalist, it's an important subject, and he can give me good information. And I know this guy knows everybody in jihad," he explained. "What the U.S. government could get out of this guy ... Well, they don't know what they don't know."

So why doesn't the FBI tap Padnos for intelligence?

"Why don't they? Good question," he said. "The U.S. government is a bunch of experts sitting in cubicles in D.C., and they say, 'We've got the situation under control.' They don't. That's why things in Iraq got worse and worse and worse."

A Fair Sheikh?

Things got worse and worse, too, in the Syrian town where the Nusra Front was holding Padnos — at least on the outside, where the al-Qaeda group was warring with the Islamic State. Padnos asked after guards who kept disappearing until, one day, a sheikh came to see him. It was al-Qahtani, the Nusra Front leader. ISIS was forcing the group out of town, he told Padnos, adding, "Wherever I go, you go. You're with me now," as Padnos recalls in the film.

"Alhamdulillah," Padnos responds. "Praise God."

Padnos accompanied the sheikh as he retreated through the Syrian desert in a convoy of white pickup trucks flying big black flags, alongside men with beards, flowing robes and .50-caliber machine guns.

"At the head of this column was me and Abu Maria and, like, 10 bags of cash," Padnos recalled. "This was the financial resources of their entire army."

To survive, Padnos adopted a "submissive and interested posture" in relation to the sheikh, "and I was interested in the grievances of an al-Qaeda leader. I wanted to hear them," he says in Theo Who Lived. Padnos became a kind of confessor for the sheikh, likening their relationship to the biblical story of Joseph and the pharaoh. "He would tell me about his troubles with ISIS; he'd tell me about his troubles with the U.S. government — how nobody understood him."

Padnos didn't have to hide his views to ingratiate himself: "I am sympathetic to their claims of victimhood at the hands of the Americans. What business did we have in Iraq?" he says in the film. "I, in fact, know the injustices committed better than they do. I think they found me to be someone who could advocate for their point of view better than they can."

During that stage of his captivity, Padnos was forced to help his captors by loading their weapons, driving their trucks and even offering advice when they asked him how to attract more Westerners into the jihad. It was the kind of assistance for which Padnos feared the U.S. government might charge him with providing material aid to terrorists.

"I'm like, 'No problem, man. I'll help you. Let's get on Twitter now,'" Padnos said. "I wanted to get on Twitter to communicate secret messages to my friends and family. But there was a lot of stuff that I would have done ... just to save my own life."

Would he have killed someone?

"Well, that's the kind of issue you think about," Padnos said vaguely. "Maybe I would have. Maybe. But could I say I deserved to live and that guy doesn't?"

The Qatari government helped negotiate his release — less than a week after Foley's televised execution — but Padnos won't reveal if a ransom was involved. A July 2015 New Yorker story titled "Five Hostages" suggested the price on his life at one point reached 22 million euros.

Though Padnos appreciates what the FBI did to help, he remains critical of the official U.S. policy of never negotiating with terrorists, calling it shortsighted and ultimately ineffectual. He blames himself for his two-year ordeal but asserts that the deaths of other American captives — notably, Kayla Mueller, Steven Sotloff and Peter Kassig, all of whom were eventually executed by ISIS — could have been prevented.

Padnos likened the situation to having boat trouble on Lake Champlain. At first you blame yourself, but eventually you expect to see the Coast Guard.

"I made that mistake. I got in the boat. But now that I'm here, can you do anything to help me?" he asked rhetorically. "And the official policy is, 'No. Fuck off!' And I don't think that's right."

Syria in Vermont

Even with the 20/20 hindsight of time and distance, Padnos still cannot say how or why he survived.

"I do know that it was not a function of my fortitude or survival strategies," he said. Although he was always hungry and lost weight, Padnos' captors gave him enough calories to survive.

"The thing that shamed me the most — and I thought it'd be a long time before I could admit to anyone — were my suicide attempts," he said. "I tried for a really long time, longer than they say in the movie."

That Padnos didn't end his own life wasn't due to any religious or moral quandary about suicide. It was entirely a practical matter: He didn't have a gun, a cyanide capsule or a rope long enough to finish the job.

Physically, Padnos looks fine now. He said he suffered only minor health issues after his release, including months of vertigo likely caused by repeated blows to his head.

Padnos also insisted he doesn't suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder; he stopped attending counseling shortly after his release, claiming he didn't need it anymore.

"Therapy for me is expressing myself, and I can do this in writing and that's good enough," he said. "I feel enhanced and rejuvenated by my experience and not traumatized."

Padnos reclaimed his name. He is currently finishing his novel, as well as a "Spalding Gray-esque" monologue, and shopping around an op-ed piece about how to resolve the Syrian crisis. During the presidential primaries, he even reached out — unsuccessfully — to Sen. Bernie Sanders' (I-Vt.) campaign staff to offer suggestions for drafting a policy position on the 6-year-old civil war.

Another good sign: Padnos hasn't lost his sense of humor, which also comes through in Theo Who Lived. Noting the punctuality of his faux friends on the morning they delivered him to Syria, for example, he calls them "very reliable kidnappers."

"The truth is, I was not laughing when this was happening," he explained at New Moon. "But a lot of people emerge from these jails, not just me, and they want to laugh at the absurd craziness of it all."

"Given what he's been through, he's remarkably similar to the guy he was before he went through all this," said Kardashian, an occasional contributor to Seven Days who has resumed biking with Padnos. "Theo's a funny guy. He's kind of a vagabond" who will "blow in and out of your life."

"If anything," Kardashian added, "he seems to be a little more compassionate and empathetic."

Amazingly, Padnos was unaware of plans to resettle Syrian refugees in Rutland next year. He said he's not concerned.

Unlike the refugees flooding into Turkey and the rest of Europe, he said, those headed to the U.S. — mostly women and children — are subjected to "extreme vetting" before they get here. Most likely fled the conflict zone years ago and have been living in refugee camps in Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan.

"These people are the sweetest and loveliest people on Earth," Padnos said. "They're going to be good and excellent immigrants. We couldn't ask for anyone better."

It's fitting that the last 10 minutes of Theo Who Lived includes footage of Padnos standing on a beach on the Greek island of Lesbos, greeting Syrian refugees in Arabic as their raft washes up on shore. In a very real sense, their hellish, odds-defying odyssey mirrors his own.

The documentary Theo Who Lived is showing on Thursday, December 1, 7 p.m., at Merrill's Roxy Cinemas in Burlington. zeitgeistfilms.com

The original print version of this article was headlined "Surviving Syria"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Media, Theo Padnos, journalism, Free Syrian Army, Bashar al-Assad, Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra, Theo Who Lived, Abu Maria al-Qahtani, ISIS, Video

More By This Author

About The Author

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Speaking of...

-

Vermont's Local News Publishers Are Endangered. Can They Be Saved?

Jul 24, 2024 -

Vermont Sportswriter Alex Wolff Helms an Anthology to Honor a Late Colleague

Jun 5, 2024 -

Bristol Journalist Alex Belth Compiled an Anthology of Classic Celebrity Profiles From the 1960s and ’70s

May 15, 2024 -

Two More Vermont Newspapers Cease Printing

Sep 22, 2022 -

Bookstock Literary Festival Returns This Weekend With In-Person Events

Jun 22, 2022 - More »

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. A Farting Bear Caught on Camera Is What We All Needed to See True 802

- 2. Rita Mannebach Traveled From Florida to Vermont to Choose How She Died Health Care

- 3. Immigration Officials Illegally Deported Vermont Family, Advocates Say News

- 4. Neighbor Charged With Murdering 82-Year-Old Enosburg Woman Crime

- 5. An Inmate’s Pleas About Her Dangerous Cellmate Were Dismissed. Then She Was Attacked. Crime

- 6. Vermont Farmers Experience a Second Devastating Summer of Flooding Environment

- 7. Some Residents Flooded Out of Plainfield Think Goddard’s Campus Should Become Home Economy

- 1. A Farting Bear Caught on Camera Is What We All Needed to See True 802

- 2. Rita Mannebach Traveled From Florida to Vermont to Choose How She Died Health Care

- 3. Moving on From Its Industrial Past, St. Johnsbury Is Attracting Young Entrepreneurs and Building a Vibrant Downtown Economy

- 4. Heavy Rains Hit Vermont Again as Flooding Washes Out Roads News

- 5. Neighbors Band Together to Save Cattle From Hinesburg Floodwater Environment

- 6. Vermont Health Officials Prepare for Bird Flu as It Spreads in Dairy Herds News

- 7. Vermont's 'Orwellian' Butter Gets a Shout-Out in Hit Show 'The Bear' True 802