Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Published October 12, 2016 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated November 16, 2021 at 6:43 p.m.

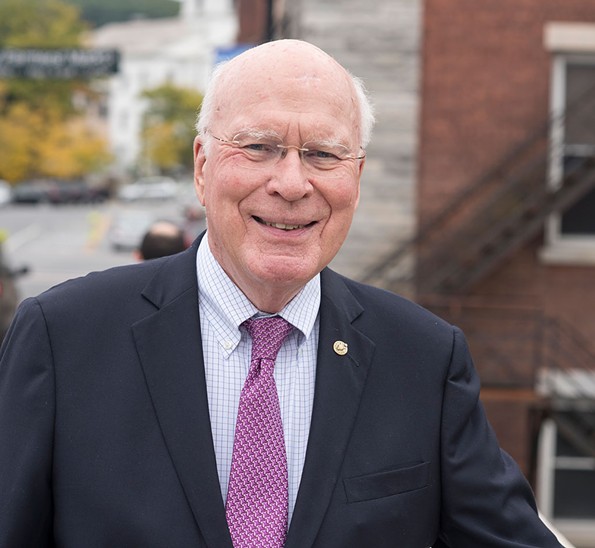

After decades in office, the dean of the United States Senate wasn't saying whether he would seek another term. But an ambitious Vermont politician wouldn't wait to find out.

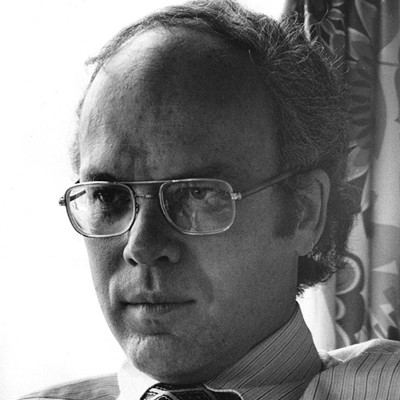

On a January 1974 trip to Brattleboro, the 33-year-old Chittenden County state's attorney, Patrick Leahy, told southern Vermont Democrats that he would seek the office "no matter who else runs."

"I want to be Vermont's next United States senator," he said.

The next month, on Valentine's Day, the dean made up his mind. George Aiken, who had served in public office since 1931 and in the U.S. Senate since 1941, told reporters in Washington, D.C., that he would return to Putney when his term expired. Back home, the speaker of the Vermont House, Walter Kennedy, fretted that Aiken's departure would leave the state's influence in Congress "at the bottom of the barrel."

"I don't like it at all," Kennedy said.

Leahy promised to make up for what he lacked in seniority with youthful vigor and idealism. At his campaign kickoff that March, the Montpelier native vowed to reverse the "frustration and disillusionment" many felt in government as the Watergate scandal brought the Nixon administration to its knees.

"It is time now to bring a fresh, new approach and leadership to government," Leahy told some 200 supporters.

Forty-two years later, as he pursues his eighth term in office, Leahy's message to voters could not be more different. Now the dean of the Senate himself, the 76-year-old argues that what Vermont needs most is not a "fresh, new approach" but a steady hand at the wheel, versed in the ways of Washington and able to deliver outsize federal funding for his undersized state.

"Politics is sometimes nothing but irony," says Steve Terry, a retired Green Mountain Power executive who worked for Aiken during his final term. "This is a case in point."

The irony is not lost on Scott Milne, a 57-year-old travel agency president who has mounted a long-shot campaign to topple the veteran senator. The Pomfret Republican, who nearly defeated Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin in 2014, has been unsparing in his criticism, referring to his opponent as corrupt, ineffectual, imperial and hyper-partisan.

"Patrick Leahy is the poster child of what is wrong with this system," Milne says.

Whether or not that's the case, few politicians have spent more time enmeshed in the system than Leahy. Next month, according to Senate records, he will overtake the late senator Carl Hayden as the institution's fifth-longest-serving member. If he wins reelection this November and completes an eighth term, the then-82-year-old lawmaker will trail only the late senators Daniel Inouye and Robert Byrd in the history books.

"I'll be younger than my predecessor was when he left," Leahy said in an interview last week in his Burlington office, referring to the octogenarian Aiken.

Leahy's longevity in a chamber that values seniority "has meant hundreds of millions of dollars of federal investments in Vermont in his current term," says his Senate spokesman, David Carle. It's the theme of his reelection campaign — expressed in television ads about securing Tropical Storm Irene aid and in federal funding announcements unsubtly timed for the campaign season.

But the state's reliance on Leahy largesse makes some Vermonters nervous — particularly as the senator shows clear signs of aging, from his slowed gait to his sometimes-slurred speech. When it comes to the state's bottom line, he has become almost too big to fail.

"My fear is that all three members of our congressional delegation are nearing possible retirement," says National Life vice president Chris Graff, a former journalist who documented Leahy's rise in his book, Dateline: Vermont. Graff notes that Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) is 75 and Congressman Peter Welch (D-Vt.) is 69. "If, over a six- or eight-year period, we had an entirely freshman congressional delegation, that would be a huge hit for Vermont."

As Kennedy put it four decades ago, the state would return to "the bottom of the barrel."

It's not just the pork. Leahy's influence and diverse interests have put a Vermont stamp on such issues as organic food standards, the elimination of land mines and the composition of the U.S. Supreme Court. In April 1975, he cast a deciding vote to cut off funding for the Vietnam War, and in December 2014 he flew to Cuba to bring home imprisoned aid worker Alan Gross — a key step toward normalizing relations with the island nation.

"This good and noble man is one of the best," says Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), the civil rights icon, with whom Leahy has worked to restore the Voting Rights Act. "No one today in America is a stronger champion for voters' rights for all of our citizens."

Throughout his campaign, Milne has tried to turn Leahy's lifetime of public service against him. The senator, he says, has become a creature of Washington, out of touch with Vermont.

Leahy bought a house in McLean, Va., in 1978 — now valued at $1.2 million — and continues to live there most of the year. Though he speaks frequently about his "farm" in Middlesex, Vt., that town's grand list indicates that his mailing address is a post office box in McLean.

According to records provided by his Senate office, Leahy has spent between 83 and 121 days a year in Vermont in the past six years. In that same period, the Senate has been in session between 125 and 162 days.

Milne appears to stand little chance of winning, and Leahy's campaign has studiously — masterfully, even — avoided engaging him. But the senator himself seems rattled by his opponent's attacks, perhaps because he has not faced a competitive race since 1992.

"I am surprised that he is wanting to run basically completely a negative campaign," Leahy said last week. "I've yet to hear what he stands for, other than he's not me. Well, no. He's not. He's got more hair!"

Asked what he would tell the Patrick Leahy of 1974 — the one who thought it necessary to bring new blood to the Senate — present-day Leahy considered the question.

"I'd say, 'You know what? I'm impressed that you've been picked as one of three outstanding prosecutors in America, and you've always shown your commitment to things,'" he began.

For the next four minutes, Leahy rattled off everything he'd accomplished by the time he challenged Aiken — even the most minor successes, such as appearing in a public service announcement about drunk driving. It seemed for a second as if he had gotten lost in his answer, but soon his point became clear: Unlike Milne, he was arguing, he had assembled a record to run on — even at age 33.

"So I'd say, 'Show you've done something," Leahy concluded. "Don't just go and say, 'Oh, I'll run. I've got a whole lot of money. I'm kind of interested in running.' Show you've done something."

No 'Bro'

On a humid July night in Philadelphia, Leahy took in the Democratic National Convention from the bleacher seats of the Wells Fargo Center. Seated to his right was CBS reporter Gayle King, who was eager to interview him about his junior colleague, Sanders, one of that night's prime-time speakers.

Since Robert Stafford retired from the Senate in 1989, Leahy had relished his role as the top dog in Vermont's congressional delegation. But, over the previous year, Sanders' unlikely presidential campaign had caught fire and turned him into political powerhouse.

Leahy's own star had fallen: When Democrats lost power in the 2014 midterms, he lost his chairmanship of the Senate Judiciary Committee and his ceremonial position as president pro tempore — not to mention the security detail that came with it. He was now playing second fiddle to his Brooklyn-born colleague.

As Sanders finished his address, Leahy stood to photograph the man he'd served beside and tussled with for 25 years.

"We've heard a lot of it before," he said of the speech, which featured themes Sanders has been raising since 1974, when he ran on the Liberty Union ticket for the same U.S. Senate seat as Leahy. Following Aiken's retirement that year, Leahy had gone on to defeat Republican congressman Richard Mallary by a mere 4,406 votes. Sanders won just 5,901 votes, but he could have cost Leahy the election.

Over the years, Leahy has occasionally infuriated his liberal base, but never as much as when he endorsed Hillary Clinton for president over his fellow Vermonter.

After Sanders won 86 percent of the vote in his home state's presidential primary, more than 5,000 people signed an online petition saying they were "disappointed" that Leahy and three other Vermont superdelegates still planned to back Clinton at the convention.

Emma Mulvaney-Stanak, chair of the Vermont Progressive Party, says she was disappointed by Leahy's decision. But she nevertheless calls herself a fan of the senior senator, hailing his work fighting for civil liberties and privacy rights.

"He's no Bernie," says Mulvaney-Stanak, who, like many Vermont politicos, interned for Leahy in college. "But on the federal level, he is almost as progressive as it gets."

Bill Lofy, a Democratic operative who served as Shumlin's chief of staff, agrees. Lofy got his start working for the late Minnesota senator Paul Wellstone and remembers Leahy taking the leftie legislator under his wing in the early 1990s.

"I think Sen. Leahy will go down as one of the great progressive icons of the past 50 years," Lofy says, comparing the Vermonter to Wellstone and Hubert Humphrey.

At odds with that assessment is Leahy's reliance upon corporate campaign cash to sustain his sprawling political organization. Over the past six years, he has raised more than $1.3 million from political action committees — many representing the nation's most powerful industries.

His top donors have included entertainment companies, such as Time Warner and Walt Disney; tech behemoths, such as Microsoft and Google; telecoms, such as Comcast and Dish Network; and military contractors, such as General Dynamics and Lockheed Martin. Two personal injury firms — the Law Offices of Peter Angelos and Girardi | Keese — have donated a collective $248,000.

All have business before the Senate Judiciary or Appropriations committees, on which Leahy serves.

While the senator maintains that the cash is necessary in a post-Citizens United world, he had relied on the same fundraising practices for decades before the Supreme Court handed down that decision in 2010. It's what motivated former Republican governor Jim Douglas to challenge Leahy back in 1992, Douglas claims.

"I felt strongly that since 96 percent of his campaign funds came from out of state, there was a valid question about who he was representing," Douglas says. "And I gather the numbers are still similar today."

In July, Milne challenged Leahy to what he called a "clean campaign pledge." It would require the candidates to refuse and return PAC money — and to limit spending to $250,000. If outside groups poured money into the race, a candidate would be entitled to spend two dollars for every one dollar targeting him.

"I mean, it's a fun thought," Leahy mused in an interview that month at the Philadelphia convention, dismissing Milne's proposal as unrealistic.

Sitting in a stairwell in the Wells Fargo Center to escape the noise of the convention hall, he defended his decision to take money from PACs.

"I don't know anybody who hasn't in Vermont," he said.

Reminded that his junior colleague had refused corporate cash — and raised more than nearly any candidate in history — Leahy pushed back.

"Well, there are a lot of PACs I wouldn't take, and they probably wouldn't give me," he said. "But no. As long as I report it — these are people. A lot of them I've gotten to know. I appreciate their support."

No Longer 35

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Sen. Leahy's Office

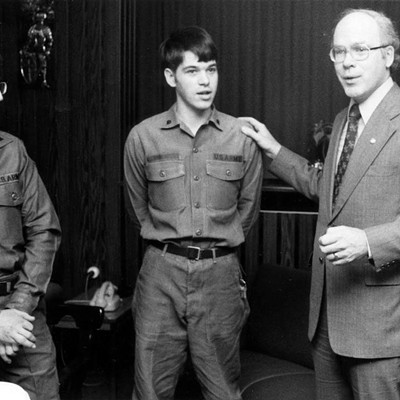

- 1975: Patrick Leahy, center, with Senators Alan Simpson, Bob Dole, Joe Biden and Charles Mathias

Early last month, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Julián Castro became the latest cabinet member summoned to Vermont for Leahy's election-year show of power.

During a roundtable discussion at Burlington City Hall, Castro listened patiently as housing officials and activists promoted their programs and sought his assistance. Seated by Castro's side, Leahy looked thrilled.

Near the end of the event, Cathedral Square CEO Kim Fitzgerald pressed Castro for several minutes on the importance of the Support and Services at Home program — called SASH — which coordinates care for Medicare recipients. She repeatedly mentioned SASH's name, drawing praise from Castro, who hailed it as innovative.

"Could I interject, too?" Leahy asked a few minutes later. "We have a program called SASH. It began at Cathedral Square."

He looked down at the folder in front of him.

"I think about 5,000 people are involved with it now," the senior senator continued. "It's an at-home health delivery service. I'm very proud of that."

Audience members glanced at one another with nervous expressions. Had Leahy somehow missed the entire conversation about SASH?

After making his point about the program, he asked if there was time for one more question. A staffer jumped up to say there was not. It was time for the next event.

"Sorry," Leahy said sheepishly. "What we're going to do is go down to the, uh, uh—"

He looked down at his folder again, evidently unsure where he was going next.

"I'm not going to give any kind of concluding remarks," Leahy continued, though the words that came out of his mouth sounded more like, "I'm not guhn-gih-ehn-ki-clude-marhk."

Champlain Housing Trust CEO Brenda Torpy, who was seated to Leahy's left, whispered insistently, "Bright Street. Bright Street. Bright Street."

"We're gonna go down to Bright Street," he said to Castro, referring to a new cooperative housing development. "I want you to see that."

Whether Leahy's health is on the decline is a matter of considerable speculation among Vermont politicians, operatives, lobbyists and reporters. His staff has insisted for years that he simply suffers from chronic laryngitis, which contributes to his gravely voice. But occasionally the issue seems deeper, such as when he confused Hurricane Katrina for Tropical Storm Irene in remarks during at least two public events.

Leahy's health is not an academic question. If there were a vacancy during his term, the next governor would appoint a successor until a special election could be held. That next governor could be a Republican — and the Senate could be evenly split.

Milne has been careful about explicitly calling Leahy too old for the job, but he has suggested that might be the case.

"I worked at my business with my mom every day until she died at 79," Milne says. "She wasn't too old. I know that. But she wasn't a U.S. senator asking for a six-year employment contract, either."

Leahy's allies are quick to bat down any discussion of decline.

"I've heard the stories, and I make a point of seeking him out from time to time, and his mental acuity is — how should I say it — markedly unaffected," says Vermont Secretary of Agriculture Chuck Ross, who spent 16 years working for Leahy. "Now, he's 76. Does he have the same energy level as 55? No ... But in terms of being able to do what he needs to do and intellectually understand what he's being asked to do, I don't see anything that suggests that his ability to do that job is compromised."

If Leahy were to leave office, the ramifications for his roughly five-dozen staffers — not to mention the state of Vermont — would be enormous. The situation calls to mind the final years of Leahy's favorite band, the Grateful Dead, during which organizational and financial pressures kept guitarist Jerry Garcia on the road past his prime.

Lofy, the Democratic operative and a Dead aficionado himself, rejects the comparison. "I think the evidence just doesn't support that," he says.

"I saw a lot of Grateful Dead shows in the early '90s, and I actually loved every one of them — and I thought Jerry was playing pretty well," he says. Switching from Garcia to Leahy, he adds, "I think that he is just as effective now as he ever has been."

The senator himself appeared eager during last week's interview to put the oft-whispered health questions to rest. Asked if he was fit to serve another six years, Leahy answered as soon as the word "serve" was spoken.

"Oh, yeah," he interrupted, as if he had been waiting for the question. "Yeah."

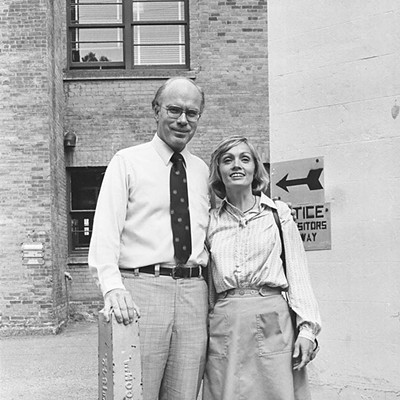

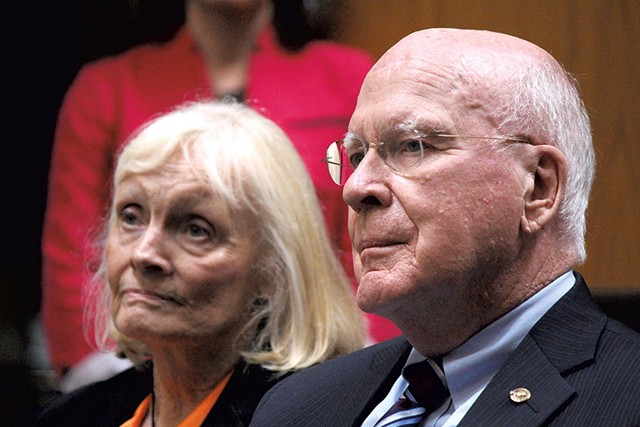

Just two months earlier, he said, he and his wife, Marcelle, had been scuba diving at a tropical destination with seven-foot sharks and massive sea turtles.

"We were swimming around that, and I said, 'It's hell to get old!'" he recalled with a mischievous smile. "I certainly didn't feel like I was slowing down ... When I'm snowshoeing around our farm, I don't feel like I'm slowing down."

So, no concerns at all?

"No. If I did, I would—" Leahy began, shifting his gaze to Marcelle, his almost-constant companion, who sat on a nearby couch. "Actually, the one concern we had on health — Marcelle's a cancer survivor ... If she had not had a totally clean bill of health, I would not have run again. So—"

He paused.

"Thank goodness you do," he said to her.

"Yeah," Marcelle said softly. "We're not 35 years old anymore."

Follow the Money

Within moments of his arrival two weeks ago at the Barre Opera House, the senator and Marcelle were holding court with a small group of local notables. Leahy had noticed Capstone Community Action executive director Dan Hoxworth wearing a Jerry Garcia tie, prompting the retelling of one of his favorite yarns — about introducing the Dead to the late South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond in the Senate dining room.

Leahy had come to Barre to hand out $1.3 million in federal funding to 19 nonprofits and municipalities. The money came from a competitive U.S. Department of Agriculture grant program, but USDA Rural Development Vermont and New Hampshire state director Ted Brady wanted to ensure that Leahy got the credit.

"I like to call him the father or the godfather of the Rural Economic Area Partnership Zone," Brady said as he introduced Leahy to a crowd of 45 grant awardees. "He created the program back in 2000. He's reauthorized it at least three times. And I believe 15 organizations in this room wouldn't be getting this funding if not for that designation."

Leahy followed Brady to the podium, looking happy to be the bearer of such good news.

"We're all Vermonters — everybody in this room. We know how to help each other. But once in a while it's nice when the feds can come. And I think this man deserves an enormous amount of credit," he said, turning to Brady. "You are the hero, and you deserve to be."

Left unspoken was the fact that Brady had spent 13 years on Leahy's staff before the senator secured him a job as the local USDA czar. Three years later, Brady was still looking out for his old boss.

"Because he's such a loyal person, people want to be loyal to him," explains Ed Pagano, a former Leahy chief of staff who went on to serve as the White House's liaison to the Senate. "He is a loyal friend to President Obama — supported his campaign early on — so certainly when I was at the White House the president wanted to make sure Pat Leahy's views were known."

Like Brady and Pagano, Leahy alums are scattered about Vermont and the federal bureaucracy. They are judges, ambassadors, mayors and college presidents. The connections enhance the senator's influence. During Bill Clinton's presidency, Pagano says, former Leahy staffer John Podesta was a key conduit to the White House, where he served as chief of staff. Now he's a conduit to Hillary Clinton's campaign, on which Podesta serves as chair.

The ex-staffers benefit even more from their connection to Leahy. Many, such as Pagano and former chief of staff Luke Albee, have gone on to lucrative careers in the lobbying world, where their knowledge of the Senate is an invaluable asset to their corporate clients. Leahy's own daughter, Alicia Leahy Jackson, has done the same. Since February 2015, she has lobbied on behalf of the Motion Picture Association of America, whose corporate members are among the senator's most generous donors.

Matthew Virkstis, a Vermont Law School graduate, spent close to a decade working for Leahy on the Senate Judiciary Committee staff. He left in March 2014 to lobby for developers who raise foreign capital through the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program. Virkstis' chief credential? According to his firm's website, when he worked for Leahy he "led drafting of legislation and staff negotiation" that extended EB-5 for another four years.

For decades, Leahy was the self-described "leading champion" of the program, which confers permanent residency on foreigners who invest at least $500,000 in qualified development projects. When he last ran for reelection, in 2010, his campaign aired a television ad boasting that, "with his help, 2,000 new jobs [would be] coming soon at Jay Peak" — an EB-5-funded resort.

Hours before federal agents raided Jay Peak last April to investigate what they called a $200 million fraud scheme, Leahy delivered a speech on the Senate floor distancing himself from the program he had long championed. EB-5 needed "a blood transfusion, not a Band-Aid," he told his colleagues. Within days, he had donated to charity $5,800 his campaign had received over the years from one of the accused fraudsters: his friend, Jay Peak president Bill Stenger, and the developer's wife.

Two weeks after the Northeast Kingdom bust, Virkstis, who declined to comment for this story, donated $300 to the senator's campaign.

Back at the Barre Opera House, Leahy stood beside Brady and Welch and handed out certificates to each of the grant recipients. They came to the podium, one by one, to pose for photos with their benefactors. Though the event had been staged by Leahy's Senate office and staffed by three of his government employees, campaign spokesman Jay Tilton was there, too, taking photographs.

In remarks to the group, Barre mayor Thom Lauzon said he appreciated the federal funding — particularly the $23,500 that would support a capital campaign for his local opera house.

"Congressman, senator, it is always a thrill to have you here, because every time you're here, our wallets seem to get a little fatter," Lauzon said. "So, hey, thanks for that."

Since Congress banned earmarks in 2011, it has become difficult to discern how much money members really bring home to their districts. Milne questions whether Vermont does better than any other small state, but Leahy's office is adamant that it does.

Carle, the Senate spokesman, maintains that his boss has secured $171 million in funding for Lake Champlain over the course of his career. He says that Leahy was instrumental in increasing FEMA reimbursement rates after Irene, bringing an additional $30 million to Vermont. And he notes that small-state minimum formulas have brought millions more for opiate abuse treatment and domestic abuse prevention.

"Have they gotten the money?!" Leahy demanded of his detractors during last week's interview. "And have they written the program?!"

Outside the Barre Opera House, Lauzon mentioned that he had known Leahy since the senator had helped his future brother-in-law obtain a visa decades earlier. But as a Republican and friend of Milne's, the mayor said he felt conflicted about who to support in the approaching election.

"I've obviously had conversations with both of them. I've really gotta make up my mind, in terms of who I'm supporting," he said. "I mean, Pat Leahy has been a great friend. He's been an absolutely great friend to Barre. I am a Republican, but, first and foremost, I'm the mayor of Barre."

Six More Years?

Last Tuesday afternoon, Leahy and Marcelle ate lunch with a handful of Middlebury College students in the basement dining area of Carol's Hungry Mind Café. It was a campaign event, of sorts, though of the heavily scripted variety.

One by one, the senator asked the students their majors and career goals, dispensing tidbits of advice, such as: Grades are important if you want to work for the State Department. At least four twentysomething campaign staffers and state director John Tracy hovered around the room's perimeter.

Though the election was five weeks away and the Senate had adjourned for the fall, Leahy had been virtually invisible on the campaign trail since conducting a 14-county kickoff tour in August. This was clearly by design: to starve Milne of the oxygen he'd need to mount a serious campaign — and to keep Leahy away from free-for-all media scrums. After nearly two weeks of repeated requests, the campaign finally agreed to make him available to Seven Days.

"It's a daunting task to run against Sen. Leahy," says Len Britton, the 2010 Republican nominee, who lost to the incumbent 31 to 64 percent.

Mulvaney-Stanak puts it in more colorful terms: "You get elected in Vermont, and you have to basically commit murder to get unelected."

By now, Leahy has reelection campaigns down to a science: Raise a ton of money ($4 million so far this six-year cycle), spend a chunk of it on TV ads, ignore your opponent and avoid debates. This fall, he's agreed to just three forums — and has refused to take part in any commercial television, radio or print debates.

"He's not a good debater," says Douglas, the former governor and 1992 nominee.

After the Leahys finished their lunch in Middlebury and more students filed into the café, Tilton, the campaign spokesman, set about recording a Facebook Live video to share on social media. The senator would sit with three students and answer prescreened questions on foreign policy.

"We wanted to start off talking about Cuba," began one of the students, Hannah Patterson of North Bennington. "My question specifically relates to how you would respond to someone who would say that this neutralization of relations would have negative effects on Cuban culture and their way of life."

"I think there will be some changes in Cuban life. I hope they will be for the better," Leahy began.

Tilton held up his iPhone to broadcast the session. Another campaign staffer snapped photos. A dozen or so Middlebury students fiddled with their smartphones, attempting to share the stream on Facebook.

This was campaigning in 2016.

In recent weeks, Leahy's operation has attacked Milne for his inability or unwillingness to articulate a single policy proposal that does not have to do with the incumbent. In one recent press release, Tilton accused the GOP nominee of running "a 100 percent negative and issue-free campaign."

Milne doesn't dispute the charge.

"You can ask me any question you want, but if Leahy's so concerned about issues, why doesn't he show up for debates?" he says. "My strategy is to talk about why we need to replace Pat Leahy."

Because the incumbent has run such a low-profile race, it's not always clear why he thinks he should be returned to public office. Asked last week to name his greatest accomplishments of the past six years, Leahy instead mentioned that, decades ago, he had insisted that the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry be renamed to include the word "nutrition."

"I got people like Bob Dole to join — a conservative Republican — on nutrition things," he said, referring to the Kansas senator, who retired in 1996. "And I've kept that going. I've kept it going through these past six years."

He mentioned the 1989 establishment of the Leahy War Victims Fund and the 2009 appointment of Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court, a confirmation fight that took place during his previous term.

And what did the senator hope to accomplish in the next six years?

"So much," he said without hesitation.

Though the Senate passed an immigration reform bill in April 2013, the House had refused to bring it up for a vote. Leahy expressed confidence that that would change in the next Congress.

"I've been having quiet discussions with both key Republicans and key Democrats," he said. "I think we can get support in the House."

Norm Ornstein, a congressional scholar at the pro-business think tank American Enterprise Institute, says he's "not surprised" that a home-state Republican would launch a "populist, anti-Washington" attack on Leahy. But he says such a move would mischaracterize what Leahy brings to the Senate.

"It's easy to attack experience and to attack Washington, but it's also a major asset. When you're around for a long time, you see things. You have a sense of history," he says. "I would say flatly there is nobody in the Senate who is more admired by his colleagues than Leahy."

Preservation Trust of Vermont executive director Paul Bruhn, who managed Leahy's 1974 campaign, says he thinks Vermont would benefit from another six years represented by his old friend.

"He's built an amazing record, on all fronts — in Vermont, nationally and internationally," he says. "And I'm very proud of him. And I think most Vermonters are."

But Bruhn says he suspects this might be the last term for Leahy.

"I haven't had that conversation with him, but I would guess that that would be the case," he says. "That he might feel that he's done his duty."

Leahy himself says he's focused on winning this election — not deciding whether to run in the next one:

"Don't you think that would be the most presumptuous thing in the world?"

The Leahy Alumni Network

In his 42 years in office, Sen. Patrick Leahy has employed countless staffers. Many have gone on to prominent careers in Vermont and Washington, D.C. Here are some of their stories:

Ellen McCulloch Lovell

A former Leahy chief of staff, McCulloch Lovell later served as deputy chief of staff to then-first lady Hillary Clinton. She retired in 2015 after 11 years as president of Marlboro College.

Chuck Ross

The former state legislator spent 16 years running Leahy's Vermont office before Gov. Peter Shumlin named him secretary of agriculture in 2011.

Ed Pagano

A former senior counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee and Leahy chief of staff, Pagano decamped to the White House in 2012 to serve as President Barack Obama's legislative liaison to the Senate. He now lobbies for Akin Gump.

Mary Beth Cahill

In 1986, Cahill managed Leahy's victorious campaign over former and future governor Richard Snelling. She later ran EMILY's List, served as chief of staff to senator Ted Kennedy and managed John Kerry's 2004 presidential campaign.

Mark Lippert

A former Leahy foreign policy adviser, Lippert later served as chief of staff to former defense secretary Chuck Hagel and as an assistant secretary of defense. He is now the U.S. ambassador to South Korea.

Luke Albee

The former Leahy chief of staff subsequently worked as a lobbyist and chief of staff to Sen. Mark Warner. He now serves as a senior adviser to Engage Cuba, a business coalition working to open markets in that country.

Miro Weinberger

During his time at Yale University, the future mayor of Burlington interned for Leahy in his Washington, D.C., office.

Beryl Howell

Howell spent a decade working for Leahy on the Senate Judiciary Committee staff. In 2010, Obama appointed her to the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, where she now serves as chief judge.

John Podesta

After working for Leahy through much of the 1980s, Podesta served in various positions in former president Bill Clinton's White House — including as his final chief of staff. Podesta founded the liberal think tank Center for American Progress and now chairs Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign.

Paul Bruhn

In 1974, Bruhn left his job in the Chittenden County state's attorney's office to manage his boss' first U.S. Senate campaign. After serving as Leahy's first chief of staff, Bruhn returned to Vermont in 1978 and became executive director of the Preservation Trust of Vermont. He remains in that role to this day.

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Politics, Patrick Leahy, U.S. Senator, Scott Milne, Emma Mulvaney-Stanak, Bernie Sanders, Julián Castro, Slideshow

More By This Author

About The Author

Paul Heintz

Bio:

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Paul Heintz was part of the Seven Days news team from 2012 to 2020. He served as political editor and wrote the "Fair Game" political column before becoming a staff writer.

Speaking of...

-

Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives

Apr 22, 2024 -

Burlington Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s First Term Starts With Major Staffing and Spending Decisions

Apr 17, 2024 -

Bernie Sanders Sits Down With 'Seven Days' to Talk About Aging Vermont

Apr 3, 2024 -

Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor

Apr 1, 2024 -

Mulvaney-Stanak Resigns From State Legislature

Mar 29, 2024 - More »

Comments (19)

Showing 1-10 of 19

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 2. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 3. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 4. Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate

- 5. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 6. A Former MMA Fighter Runs a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Cabot News

- 7. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News