Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Preside Show: An Ugly Estate Case Spotlights a 'Side' Judge

Published February 17, 2016 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated April 13, 2016 at 7:51 p.m.

Paul Kane filed a motion to try to avoid testifying in Windsor County Probate Court, but a judge ordered him to talk. As soon as he took the witness stand last November, it was obvious why he'd been reluctant. For 90 minutes, an attorney grilled Kane about whether he'd bilked an elderly woman with Alzheimer's disease of roughly $500,000.

Brattleboro attorney Jodi French asked Kane why, after the ailing Catherine Tolaro granted him power of attorney, he purchased an $180,000 annuity with her money and named himself the beneficiary.

Under French's questioning, Kane claimed that he did so with Tolaro's interests in mind.

"Making sure if she needed money for care, she could get it," Kane stammered.

"Was there any other function in your mind?" French asked.

"No, making sure if she needed the money for care, we could get it," Kane repeated.

Despite his apparent discomfort throughout the hearing, Kane knows his way around the courtroom. In fact, he's a Windham County assistant judge who was elected two years ago. But like most of Vermont's 27 other assistant judges, who advise regular judges in civil and family court cases and occasionally preside over minor cases, Kane does not have a law degree.

Nonetheless, attorneys in the Tolaro estate case say Kane, 63, may have flouted laws and regulations when he converted the funds of the elderly woman he called his "aunt." They are considering whether to refer the case for further investigation to the Department of Financial Regulation, a state agency that regulates bank transactions, once the estate is settled.

Kane has claimed that any irregularities in his handling of Tolaro's estate were due to mistakes and poor understanding of relevant laws. He says he is the victim of "character assassination."

"It's a separate issue, what I do as far as the judgeship, and the accusations out there," Kane, a Westminster resident, said in a recent interview.

He said that he and his late wife were simply trying to help Tolaro. "Nobody is talking about the care," he said. "Did I understand all the statutes? Probably didn't look into them as much as I should have. I still don't see that I did anything that was terribly wrong."

The ongoing case is the latest controversy involving assistant judges, colloquially known as "side" or "lay" judges, who retain an antiquated role in the Vermont judiciary despite repeated attempts to strip them of power.

In recent years, side judges in Vermont have been caught directing taxpayer money to their own charities, shoplifting from local stores, doling out bonuses to themselves from public budgets and accusing each other of assault.

Those embarrassing episodes, along with concerns that side judges lack legal training and operate with almost no oversight, have fueled arguments against preserving their positions.

Their harshest critics tend to be traditional judges, some of whom believe that "these people aren't really adequately trained and prepared, and they ought not participate on important decisions in people's lives," said Vermont Law School professor Peter Teachout, who has consulted for the Vermont judiciary. "A prevailing view — not a unanimous view — in the judiciary is that they couldn't be relied upon to perform even a limited judicial function. There's been clear hostility to allowing lay judges to have any legal function."

A Side of Drama

Vermont side judges trace their roots back to 1777, when the state, then a republic, adopted a constitution. At the time, traveling judges from as far away as Boston and New York City visited Vermont counties to settle long-simmering disputes. Wary of outsiders meddling in their affairs, Vermonters created the office of "side judge" in statute to ensure that local opinions and customs were recognized during legal proceedings.

In today's modern, professional judicial system, lay judges serve two roles: They assist in court cases and run county governments.

Voters in each Vermont county elect two side judges, who serve four-year terms. As their nickname implies, they sit alongside judges in civil cases and family cases. They cannot participate in issuing legal rulings, but they can help the primary judges — lawyers appointed by the governor — sort through the underlying facts of a case.

Some side judges receive special training that allows them to preside in small claims, traffic and uncontested divorce cases. But most, like Kane, appear in court only alongside primary judges and have no decision-making power.

Outside the courtroom, side judges also serve as county administrators, bearing sole responsibility for setting county budgets and supervising county employees. Though county governments are weak in Vermont — most of the power, and money, resides in individual towns, cities and the state legislature — counties are responsible for maintaining a sheriff's department and courthouse. County budgets average around $500,000; Chittenden County's, at $1.1 million, is the largest.

Remarkably, side judges get to set their own pay — generally between $20,000 and $40,000 annually — and hours for what amounts to a part-time, hybrid job.

It's unorthodox, to say the least. And the Vermont judiciary has tried over the years to rein in the job description. In 1976, the Vermont Supreme Court ruled that side judges could not decide matters of law in criminal cases. In 1983, the court stripped them of their right to decide most civil cases. In the late 1980s, laws were changed so lay judges no longer have a say in sentencing.

In the years since, incidents of petty corruption and controversies have drawn negative attention to this vestige of Ethan Allen-era law and order.

In 2014, longtime Washington County side judge Barney Bloom stepped down after he was accused of repeatedly shoplifting from three Montpelier stores over several years. He allegedly made a habit of stealing newspapers, soup and coffee from the Uncommon Market, Bear Pond Books and Capitol Grounds Café. When a formal reprimand from the Judicial Conduct Board came later, Bloom, who had served 15 years, did not contest it.

In 2009, the Stowe Selectboard publicly protested a decision by Lamoille County side judges Karen Bradley and David Williams to grant themselves raises that nearly doubled their compensation. The pay hikes withstood the challenge.

In 2008, the Judicial Conduct Board suspended former Windsor County side judge Bill Boardman for six months after finding that he had arranged the sale of county property to a nonprofit that he had founded and helped to run. The county sold the former Windsor County Sheriff's Office in Woodstock, appraised at $250,000, for $71,000 to Emerge Family Advocates, a nonprofit visitation center for parents and children going through family court cases. The county also funneled $12,000 annually to Emerge, the only charity that it supported.

"The judge appears oblivious to the fact that the trappings of his office are a public trust," the conduct board wrote of Boardman.

In 2007, Orange County side judge Prudence Pease voted herself a $2,800 Christmas bonus, one in a series of incidents that infuriated county personnel. Pease later filed a police report claiming that the county clerk had slapped her. Police investigated but declined to file charges. The Judicial Conduct Board ordered Pease to take a class in "judicial ethics." Former Vermont auditor Tom Salmon found missing money and other problems in the county's books, and Pease lost a bid for reelection in 2010.

In 1998, the Vermont Supreme Court had the last word on a public feud between Chittenden County side judges Althea Kroger and Elizabeth Gretkowski. The two had become "embroiled in conflicts over the administration of county business," according to the Supreme Court decision, and the squabbles played out in the pages of the Burlington Free Press and Seven Days. In the end, that's not why the court suspended Judge Kroger for a year; it's because she lied under oath during a Judicial Conduct Board hearing.

"No One Stepped Up"

Paul Kane's legal drama doesn't help the case for side judges.

Like him, Catherine Tolaro was a Bellows Falls native. The vivacious brunette was active in several nonprofits and community groups, including the Rockingham Hospital Auxiliary and the local women's club. "Kay," as she was known, married twice but had no children.

"She was wonderful," according to her sister-in-law, 88-year-old Gloria Carr, who also lives in town.

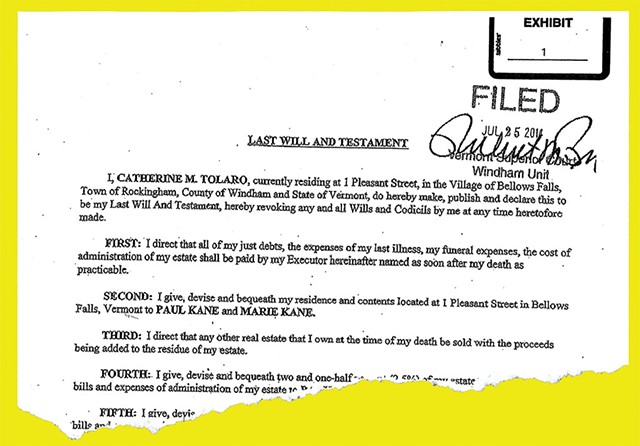

In the fall of 2009, doctors at a local health clinic determined that Tolaro was in transition from the early to middle stages of Alzheimer's disease, according to court documents. She drafted a will several months later, naming her attorney, Michael Harty, as its executor. The document, signed by Harty, gave Tolaro's home to Kane and his wife, left 15 percent of her other assets to a church and three charities, and split the rest of the estate into thirds, granted to Kane; her nephew, Michael Tolaro; and Carr and her husband, James.

Tolaro's decline was swift. Shortly after the diagnosis, she became confused and panicked while standing in her driveway one night, according to interviews and documents.

None of her blood relatives was in a position to help: a brother and nephew lived in Connecticut; Carr was too elderly to care for her.

Kane and his wife, Marie, had a close relationship with Tolaro. She had been the second wife of the late James Tolaro, Kane's father's brother-in-law.

The Kanes brought Tolaro into their Westminster home, where she lived in a spare bedroom for 31 months.

"No one else — when, literally, a lady was standing in her driveway saying she was scared to be in her home — offered help," Kane said. "No one stepped up afterward." In court documents, Kane said that he and his wife made Tolaro's meals, cleaned up after her incontinence, took her to medical appointments and provided "around-the-clock care."

Around the time that Tolaro moved in, she granted Kane power of attorney, giving him control over her legal and financial affairs. In January 2010, Tolaro had a net worth of $767,500, including her home on Pleasant Street in Bellows Falls, a rental house nearby, and several savings, money market and stock accounts, according to court documents.

She appeared to be doing well, according to Carr, who visited Tolaro daily for as long as she could.

"I observed Catherine Tolaro in need of constant comfort and care," Jane Ryan, a friend who said she stopped by twice a week, wrote to the court. "The Kanes would cook meals for Mrs. Tolaro, do her laundry, assist her with bathing and bathroom needs, and help her with dressing ... It was rare to see the Kanes in the community without Mrs. Tolaro."

Kane had worked as a Department of Corrections probation officer and as a caseworker for the Department for Children and Families. In 1988, he opened PK's Public House, a sports bar in downtown Bellows Falls. He sold the place in 2005.

Shortly before his wife died of cancer in June 2012, Kane determined that he couldn't care for Tolaro alone. He placed her in an assisted care facility 30 minutes away, in Windsor.

Tolaro died in the Ascutney House on April 21, 2014.

By then, attorney French says, Tolaro's net worth of $767,500 was nearly gone, thanks to "Paul Kane's numerous breaches of his fiduciary responsibilities."

Although her will listed several beneficiaries, including local charities St. Charles Church, Our Place Drop-In Center, Bellows Falls Knights of Columbus Scholarship Fund and Parks Place Community Resource Center, there was almost nothing left for the beneficiaries to split.

The only significant asset left was Tolaro's home on Pleasant Street, valued at around $200,000. In her will, Tolaro had already signed it over to the Kanes.

Too Many Lawyers?

Great American Insurance Company, which had sold Kane the $180,000 annuity, raised the first red flag.

In a May 2014 letter to Kane — a month after Tolaro's death — Great American wrote that "general principles of law against conflicts of interest" prohibited someone granted power of attorney from being the beneficiary of an annuity. Great American told Kane it would refuse to pay him until all of Tolaro's potential beneficiaries had agreed to it.

But after they heard from Great American, Tolaro's nephew, Michael, and St. Charles Church retained Bellows Falls attorney Ray Massucco.

"They're not greedy people," Massucco said. "They were looking for an explanation."

Once Massucco dove into the case, he said he discovered other irregularities. But by the time Tolaro died, Harty, her initial executor, had retired, and he declined to serve as the executor. Vermont law requires that a new executor be appointed.

A Windham County judge chose Christopher Moore of Bellows Falls in September 2014.

Within days, Moore's paralegal sent a letter to Tolaro's beneficiaries, asking them to tell Great American that Kane should receive the annuity. The letter did not mention that Moore was also Kane's attorney.

Moore eventually stepped aside and, in a letter filed with the court, acknowledged a conflict of interest "ha[d] evolved." Moore's office said he was not available to comment.

A probate court judge appointed French to replace him.

Her first act was to request the case be transferred from the Windham County Probate Court, which is located in the same building where Kane works on family and civil court cases — but not probate court ones.

Superior Court Judge Brian Grearson sent the case to Windsor County Probate Court, in Woodstock. There, the legal sparring has only intensified.

"Given her diagnosis in 2009 and other factors, I believe she was highly susceptible to exploitation as a vulnerable adult," French wrote of Tolaro in court documents.

Kane had closed out Tolaro's accounts, French wrote. He purchased the annuity in which he was the sole beneficiary. He wrote checks to himself from the other accounts. He loaned a friend $24,000 to buy a mobile home and $50,000 to the man who bought PK's Public House from him, and there is only a partial record, French said, of monthly repayments being paid back into Tolaro's accounts. He bought a $4,000 pellet stove at his home in Westminster with her money, according to court documents. *

"Rough Justice"

Side judges cost the state of Vermont roughly $400,000 annually, according to the Court Administrator's Office. The judiciary pays them $161 for every day they preside alone on traffic, small claims and uncontested divorce cases, in addition to salaries they award themselves on the county level for sitting beside judges in civil cases.

During the Great Recession, the Vermont Judiciary convened a commission, led by Chief Justice Paul Reiber, to trim $1 million from its budget and create a more efficient legal system.

Reiber's commission held more than a dozen meetings across the state and consulted with judges, lawyers, lawmakers, outside experts and court clerks.

One suggestion came up again and again: Strip side judges of their legal authority. Let them run the counties, but keep them out of the courtroom.

Records of the commission's work are littered with insults against side judges and pleas to get rid of them.

"Side judges are not an appropriate use of resources ... Elected judges are not appropriate, and their jurisdiction should be minimized," the Windsor and Orange County bar associations wrote to the commission.

A group of legal experts worried that getting rid of side judges would be a "political nightmare" but suggested that publicizing more of their "abuses" could help sway public opinion.

"Unless we want small claims court justice to be rough justice, not based on law, lay judges simply cannot meet the requirements of this role," Bristol attorney James Dumont wrote the commission.

The only people who opposed the idea, it seemed, were the side judges themselves, who angrily wrote that they opposed the commission's "outright dismissal of the value and input of the elected judges of our state."

Reiber presented to the legislature the commission's final report, which recommended doing away with side judges.

"There is simply no evidence that having more than one judge improves the quality of justice," Reiber wrote. "It makes sense to eliminate the cost of this redundancy."

The legislature adopted many of the commission's recommendations. But side judges survived, thanks largely to the intervention of powerful legislators, including Senate Judiciary Committee chair Dick Sears (D-Bennington), a longtime side judge advocate.

"I think they perform an important judiciary function," Sears said. "They take some of the workload off of the sitting judge. They also have become better trained over the years. I've seen improvements."

Reiber's office did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Many side judges say their reputations have been tarnished by the actions of a few bad apples.

"The assistant judges I've had contact with are pretty ethical," said Bennington Assistant Judge Jim Colvin, head of the Vermont Association of County Judges. "Lack of discretion is not confined strictly to assistant judges. When you're dealing with human beings, your position or title doesn't exempt you from those pitfalls of humanity."

Orange County side judge Joyce McKeeman said that she reads Vermont Supreme Court decisions in her spare time and has voluntarily attended legal trainings to sharpen her skills.

"I know the rap against assistant judges comes from the bar and other judges," she said, but she dismissed the notion that holders of that office might be more susceptible to corruption. "We know that elected officials in Vermont and elsewhere occasionally engage in unprofessional conduct. That happens for any group. That's just a way of the world."

Neither Colvin nor McKeeman knew Kane, who has held office for less than a year and a half. When he ousted an incumbent Democrat in 2014, the rookie side judge ran on his record of representing the DCF and DOC in court.

Kane, who makes about $35,000 from the county for serving as side judge, said he works between 15 and 20 hours a week, primarily sitting on family court cases. He hears matters such as requests for restraining orders and child support cases. Those court hearings are closed to the general public.

"I bring to the position some history other people don't have sitting there," he said, referencing his former state jobs.

Owning a sports bar was also part of his work experience. In early 2015, Kane announced that he would again be running PK's Public House, after the man who bought it from him could no longer make monthly payments on Kane's loan to him.

Soon after, the Brattleboro Reformer reported, "He is proud to say customers can enjoy great beer and spirits in a place that also makes families and women feel comfortable."

Abuse of "Power"?

click to enlarge

- © 2016 google

- Catherine Tolaro's home, which was left to Windham County Side Judge Paul Kane in her will

Should a Vermont side judge such as Kane have understood the legal limits of "power of attorney?" Those rules, which are designed to prevent abuses, are well-known to anyone involved with the law, according to Massucco. Individuals vested with power of attorney are prohibited from accepting "gifts" from the people they are aiding, unless the agreement explicitly allows for it.

"The power of attorney executed by Kay did not grant Marie Kane or Paul Kane the authority for self-compensation, dealing or gifting," French wrote in court documents.

"I had no idea what that even was," Kane insisted in an interview. "Did I follow all the statutes? Probably not. I wasn't looking at gifts or any of that stuff. Were all t's crossed and i's dotted? Probably not."

But there's no money "missing" from Tolaro's estate, Kane claimed, contrary to what attorneys are saying. He said it all went to her medical care — at his home and in the assisted-living facility. During the court hearing, French said that Kane has not provided documentation to support his claims.

In an interview, Kane said Tolaro's two-year stay at Ascutney House cost roughly $100,000, which he paid with money from her various accounts. After lawyers began challenging his handling of the estate, Kane submitted an invoice claiming that he was owed nearly $800,000 for the 31 months that Tolaro lived at his home.

Kane was also eager to explain to French and the court how buying an annuity payable to him helped Tolaro.

Kane said he was being a responsible financial manager, trying to generate a higher return on Tolaro's money than a traditional savings account would garner. The annuity, he said, guaranteed 4 percent interest. He said he always intended the proceeds to benefit her or to wind up in her estate.

"I was assuring her money was going to make money for her, and I had the ability to get that money into the estate upon her death," he said.

Attorneys involved in the case say his claims are bogus. While some of Tolaro's money may have gone for legitimate medical care, they question how buying an annuity payable on her death could have helped her.

French has received permission from a judge to dig further into Tolaro's and Kane's financial records. She told Seven Days that she doesn't think she has a full accounting of where Tolaro's assets and income went.

"It's just crap, you know?" Kane said. "I just wish truth would be the only thing people use. It bothers me. I think I've got a pretty good reputation. I was elected to a position, so I must have some sort of decent reputation. And now this, you know?"

To bolster his case, Kane urged Seven Days to contact Carr, who confirmed the Kanes were diligent caregivers to her sister-in-law.

"She was well taken care of," Carr said. "She had a lovely bedroom; they took her to church; they took her to lunch and dinner. I have no questions there. None."

But Carr told Seven Days that she is concerned about how Kane handled Tolaro's financial affairs. Carr expected she would inherit Tolaro's home on Pleasant Street when her sister-in-law died. She was surprised, she said, when the will gave it to Kane. The additional accusations about Kane draining her accounts, she said, were also alarming.

"I trusted him from the beginning," Carr said. "Now I don't know what to think."

*Correction, February 17, 2016: A previous version of this story said there was no record of repayments of two loans Paul Kane made with Catherine Tolaro’s money. According to attorney Jodi French, she found records of some payments, but not the full amounts. Further, a previous version of this story erroneously reported that French found no record of Tolaro’s monthly Social Security income. According to French, she did find records of her Social Security income.

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Crime, court, side judges, legal, Paul Kane, Catherine Tolaro

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Strict Laws Govern Rental Security Deposits. What If a Landlord Ignores Them?

Aug 30, 2023 -

Vermont and Its Schools Sued Over PCBs. Will They Win?

Jul 19, 2023 -

Video: Diane Sullivan Talks to Weed Shoppers on Opening Day at FLŌRA Cannabis in Middlebury

Oct 6, 2022 -

Vermont Issues First Three Licenses for Retail Cannabis Sales

Sep 14, 2022 -

Vermont's Cannabis Growers Are Ready — But Their Permits Aren't

Apr 25, 2022 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million News

- 2. Legislature Advances Measures to Improve Vermont’s Response to Animal Cruelty Politics

- 3. Vermont Rep. Emilie Kornheiser Sees Raising Revenue as Part of Her Mission Politics

- 4. Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders as Education Secretary Education

- 5. Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State Board of Ed Chair's Testimony Education

- 6. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis

- 7. Norwich University Names New President Education

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. Queen of the City: Mulvaney-Stanak Sworn In as Burlington Mayor News

- 7. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News