Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Scott Official Pushes Back on Former State…

-

News

Burlington Budget Deficit Balloons to $13.1 Million

-

Education

Senate Committee Votes 3-2 to Recommend Saunders…

- Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote Education 0

- Norwich University Names New President Education 0

- Media Note: Mitch Wertlieb Named Host of 'Vermont This Week' Health Care 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Public Health Expert Tracy Dolan Readies Vermont for Afghan Arrivals

Published October 27, 2021 at 10:00 a.m.

Tracy Dolan was traveling one night on a remote road in northeastern Afghanistan when local warlords stopped the car she was riding in. It was 2002, just a few months after the fall of the Taliban, and Dolan was working for the nonprofit ChildFund International to set up schools for Afghan children, most of whom had never had formal education.

The kidnapping of Westerners was not yet common, but travel in isolated areas was always perilous because of land mines and heavily armed militants.

"It's funny. When you're young, you don't think much about security," said Dolan, who was 32 at the time but had already lived and worked in several conflict-ridden countries in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Dolan didn't speak Dari or Pashto, Afghanistan's most common languages, but from the tone and demeanor of the militants, who carried Kalashnikov rifles, she knew they meant business. Dolan's Afghan guides answered their questions calmly and quickly, and soon the gunmen let the group continue.

Later, one of the interpreters told Dolan he'd spun a yarn about how they were all working for the United Nations so that the warlords wouldn't harass them further. It was one of several occasions, Dolan said, when her Afghan partners had risked their own lives to save hers.

Nearly two decades later, Dolan is looking forward to repaying such courage by helping compatriots of the Afghans who protected her. In September, Gov. Phil Scott appointed her director of the Vermont State Refugee Office. Her first order of business will be to coordinate state and federal assistance to as many as 100 Afghan refugees approved for resettlement in the Green Mountains. All were displaced by the rapid fall of Afghanistan's government in August, including many who worked with the U.S. military during the 20-year war.

"The idea that I might play any small role at all in making Vermont more welcoming feels great," Dolan remarked during an interview soon after starting her new job.

Vermonters may recognize Dolan from her most recent position as deputy commissioner of the Vermont Department of Health, where she was often the face and voice of public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. But the 51-year-old Jericho woman, who grew up in a working-class family in northern British Columbia, also brings to her new job more than a decade of international experience helping people in dire circumstances. Widely praised for her emotional intelligence and ability to communicate directly but compassionately with the public, Dolan also excels at an unusual side gig — standup comedy.

In this new stage of her career, Dolan will need to use all her skills to help refugees and asylum seekers start anew in an unfamiliar culture — and help Vermonters acclimate to the state's changing demographics.

Right for the Job

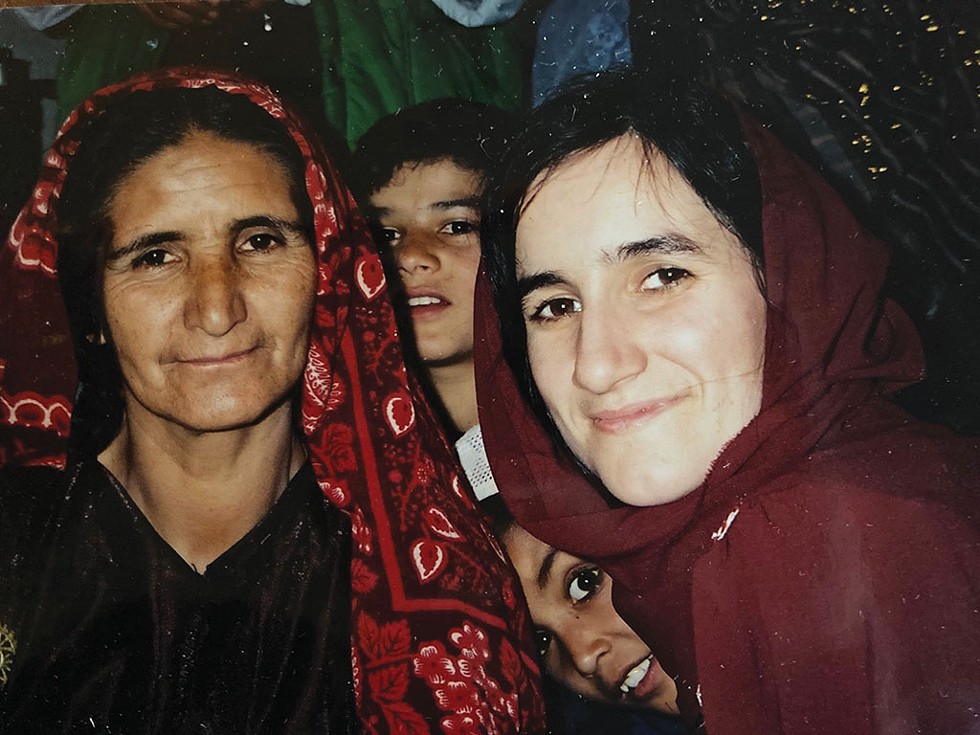

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Tracy Dolan

- Tracy Dolan (right) in Takhar Province, Afghanistan, in 2002

Normally, the position of deputy health commissioner doesn't attract much media attention. COVID-19 changed that, and until she left the health department in August, Dolan routinely appeared on radio and television to answer questions about the virus, vaccines, the Delta variant and the like.

"Honestly, nobody really knew who I was until the pandemic," Dolan said.

Though running the State Refugee Office may seem like a departure from her previous job, Health Commissioner Dr. Mark Levine, Dolan's former boss, said the fundamental nature of her work won't change. She still will be focused on what he called "the social determinants of health" — access to medical and mental health care, food, housing, education, and employment.

"I think that's going to allow Tracy to have an amazing merger of her skill sets," Levine said.

Running the State Refugee Office, a tiny operation where she'll have just one employee, will require more than the ability to navigate state and federal bureaucracies. Dolan must also work closely with local refugee advocates, including the Vermont office of the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, the new Brattleboro chapter of the Ethiopian Community Development Council, and the Champlain Valley Office of Economic Opportunity.

Dolan already forged many of those relationships during the pandemic, Levine said, when she worked to boost COVID-19 vaccine rates among Vermont's New Americans and other communities of color.

Dolan will also need to assuage the fears and apprehensions that some Vermonters may have about foreigners resettling in their communities and encroaching upon an already tight housing market. Even before the first Afghans arrive, the media are watching to see whether Dolan can prevent the kind of controversy that polarized Rutland residents in 2016 after the city tried, unsuccessfully, to resettle 100 Syrian refugees.

Ultimately, Dolan's success may hinge on her ability to communicate effectively and sympathetically with a cross section of Vermonters. It's a skill for which she was widely commended during her time at the health department.

"She did that masterfully," Levine said. "For many people in the state, Tracy was the reassuring voice about the pandemic."

Jane Lindholm, the former longtime host of Vermont Public Radio's "Vermont Edition," agreed. Soon after the pandemic began, Dolan became a weekly guest on the midday news program, fielding questions from Lindholm and listeners for the better part of the hour.

"The thing that I especially appreciated about Tracy was that she was straightforward," Lindholm said. "In interviewing public officials, I get really frustrated when I feel like they don't answer the question. Tracy was really good about saying, 'I don't have an answer to that question.' That's refreshing, because it helps to build trust with the journalist but also [with] the audience."

Dolan also did something else that impressed the 20-year veteran of public radio: She talked about the pandemic in personal terms.

"Tracy liked to use her own family as an example in her answers," Lindholm added. "She didn't hold herself apart from everyone else ... She would empathize in a very human way."

Another Kind of Headliner

On a recent Friday evening, Dolan got personal again about herself and her family in a very different forum — onstage at the Vermont Comedy Club in downtown Burlington. Dolan, who's been moonlighting as a standup comedian for eight years, was opening four shows that weekend for the club's headliners.

She took the stage in a black leather jacket, jeans, espadrilles and hoop earrings that dangled beneath her short, jet-black hair. To warm up the crowd, she told self-deprecating and (mostly) clean jokes about herself and her two teenage daughters.

Divorced shortly before the pandemic began, Dolan riffed about being a single mother in her fifties and dating again. She did one bit about meeting an attractive man whom she considered "a nine" while she judged herself "a six, though with the exchange rate, I'm closer to an American four."

Dolan also riffed about her childhood spent in a trailer park.

"I'm not trying to sound like I'm that much better than you, just because I grew up in a house that could move," she joked. "My parents decided to raise me in a home that a mild breeze could lift up, magically spin around and turn into a meth lab."

Though seating capacity was limited for social distancing, the club filled with laughter. Dolan avoided jokes about controversial subjects, especially those related to public health, such as vaccine skepticism.

"I might do something tongue-in-cheek about vaping," Dolan explained about her comedy routine. "But for the most part it's all about my family, my upbringing and my relationships."

About the only pandemic-related joke Dolan told that night touched on her difficulty returning to social situations after the lockdown. When she realized that she was struggling to focus during face-to-face conversations, Dolan told the audience, she took an online test to see whether she had attention deficit disorder; it came back negative.

"Turns out what I do have is a profound lack of interest in other people's lives," she quipped.

The joke got plenty of laughs. But to anyone in the room who knew that Dolan had spent the last 19 months trying to prevent Vermonters from dying of COVID-19, nothing sounded further from the truth. Actually, Dolan has spent much of her career deeply invested in the lives of others.

Navigating Cultures

Dolan grew up in Prince Rupert, a port city of about 12,000 people on British Columbia's northwest coast, which she describes as "the rainiest place that people inhabit in North America."

By comparison, "Seattle feels like Florida," she said during an interview at her new state office in Waterbury.

Dolan was the youngest of six children in a lower middle-class family. Her childhood home — "a double-wide!" she proclaimed — was at the end of a cul-de-sac, with a basement and garage that her father had built, a yard with rosebushes, and a basketball hoop out front where neighborhood kids played.

Dolan's mother stayed at home to raise the kids, and her father worked as a millwright at the local grain elevator. Both parents were strongly pro-union and devoutly Catholic.

"Like, very Catholic," she clarified. "We said the rosary every day on our knees after dinner. I don't know of any family that was more Catholic than us on this continent."

Because the family's budget was tight, Dolan went to work at an early age. During summers in high school, she joined her father at the grain elevator doing manual labor, such as bleeding brakes on freight trains. The union jobs paid well, and she earned about $10,000 each summer, which she put away for college.

Neither of her parents finished high school, but they were worldly in other ways, she said. Her father was an avid reader, and every night the family watched the evening news together on TV. As a girl, Dolan fantasized about becoming a television journalist.

She studied political science and economics at the University of British Columbia and volunteered at the student-run radio station. The day after graduating, at 21, she boarded a flight for Tokyo to take a radio job at NHK, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation.

During her work there, she interviewed physicians from Doctors Without Borders, a conversation that sparked her interest in public health and led her back to Canada to earn a bachelor's degree in public health education. In the mid-1990s, while finishing a master's degree in community health, Dolan took a part-time job doing HIV prevention work in First Nation communities. The prevalence of HIV infection among British Columbia's Indigenous people was among the highest in Canada.

Much of Dolan's work involved dispelling myths and misconceptions about how HIV spreads and breaking the stigma associated with the disease. She worked closely with First Nation elders to use their culture and traditions to reach street youth who were using intravenous drugs and sharing needles.

In 1999, as HIV ravaged Africa, Dolan took a job in Malawi for the nongovernmental organization Save the Children. After two years there and a year in Uganda, she became HIV project officer for ChildFund International, work that took her to Kenya, Zambia, India and Thailand.

In 2002, Dolan crossed the border from Tajikistan into Afghanistan with $10,000 hidden in her shoes and another $10,000 in her bra — "$5,000 per cup," she quipped.

Dolan's anecdote sounds like the setup for one of her jokes, but at the time it was no laughing matter. In those days, she explained, there was no way to electronically transfer funds into Afghanistan, so cash had to be smuggled in.

"Nobody told us whether we'd get in trouble for doing it," she said, "but for sure they'd take it from us."

Dolan was on a mission to set up temporary schools, ostensibly to teach children how to read and write, she said. But the schools also provided "normalizing activities" for children who'd never known anything but poverty, war and destruction.

"Our local Afghan colleagues — men and women who were program staff, interpreters, drivers, engineers — they were the engine behind the work and made it all possible," Dolan recalled.

Because the Taliban forbade girls from attending school, her NGO required that communities who received its aid educate girls as well as boys.

One of Dolan's first tasks was to recruit "teachers" — basically, any adults who could read and write — and give them several days of training. The Afghan educators also had to ensure that students showed up on time each day.

"Some of the communities were still governed by warlords," Dolan recalled. "Sometimes when we arrived, to call a meeting to order, someone would fire a round from their Kalashnikov into the air, and that served as the bell, so to speak."

Even as Dolan and her team tried to introduce Western values of gender equality, they respected local customs and sensibilities. Dolan never donned a full burka, but her clothing covered most of her body, from neck to ankles. And while she never felt threatened as a woman, "If I showed up without my male colleagues in a community or village, I wouldn't be taken very seriously."

In one village, the elders told Dolan that there were no women who knew how to read or write — that is, until someone pulled her aside and showed her where those women lived. Nevertheless, Dolan was unsuccessful in negotiating their inclusion in the teacher training program; the male elders wouldn't let them participate.

"Other than navigating our way through land mines on the roads, the hardest part about working in education in Afghanistan was navigating the cultural and gender norms," she said.

A month after that initial teacher training, Dolan and her team returned to the village to see whether classes were still meeting; they were. In fact, one teacher told her that the most challenging part of teaching girls was getting them to leave once classes were over.

"I hope they are OK now," Dolan said, reflecting on recent events in Afghanistan, "and I hope for the women these girls have become."

From Afghanistan to Vermont

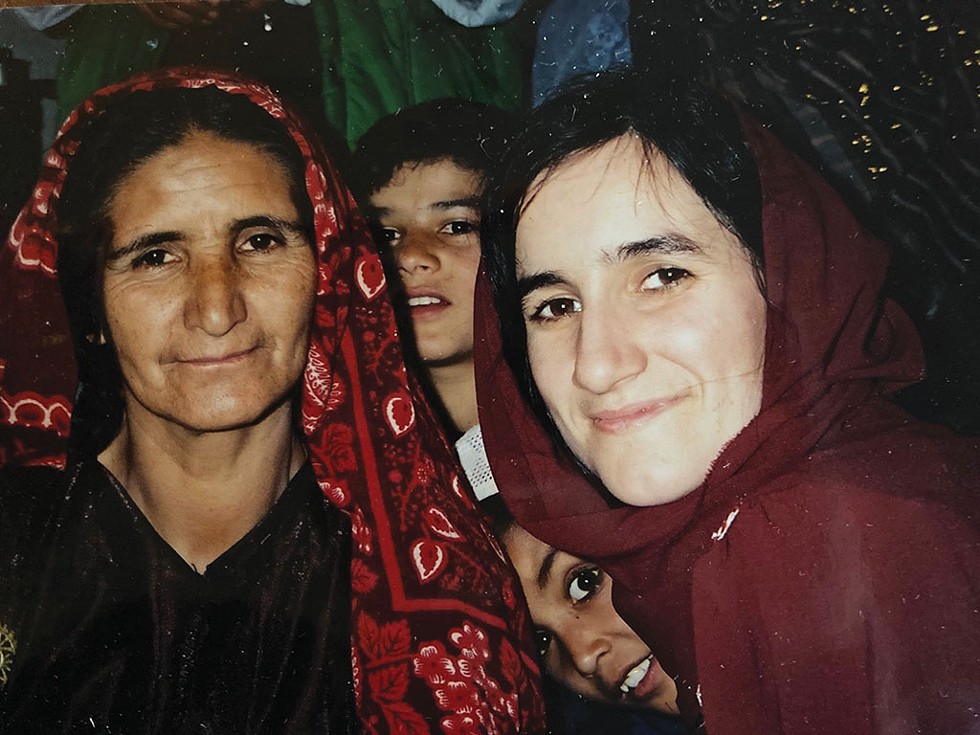

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Tracy Dolan

- Afghan boys and a teacher at a school Tracy Dolan and her team helped establish in Takhar Province

During her stint in Afghanistan, Dolan met her future husband, Chanon Bernstein, who worked on the team setting up schools. The couple married in 2004 and had their first daughter the following year. They adopted their second daughter in 2009.

Because Dolan and Bernstein didn't want to travel internationally while raising their girls, the family resettled in Vermont, where Bernstein grew up. In March 2009, Dolan arrived in Vermont from Ethiopia on a Friday and started her job at the Vermont Department of Health on the following Monday.

She began as the department's director of planning, overseeing the Office of Minority Health and the Office of Rural Health and Primary Care. In January 2011, then-governor Peter Shumlin appointed her deputy health commissioner.

Sharon Moffatt, Vermont's health commissioner from 2006 to 2008, never worked with Dolan in state government. But the two met when Moffatt was with the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, where Dolan chaired a national committee of high-ranking health officials.

"I always found Tracy to be a great listener," Moffatt said. "Tracy didn't need to be the front person all the time."

Later, when Moffatt worked for the CDC Foundation, a nonprofit that supports the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, she and Dolan cooperated to fill vacant health department positions such as contact tracers, case investigators and laboratory technicians. (Early in the pandemic, Dolan did some contract tracing herself because the state was short-staffed.)

"I worked with Tracy almost up to the day she left" in assessing the health department's needs, Moffatt said, noting Dolan's unwavering dedication.

Moffatt said she was sad to hear that Dolan had left the health department. But speaking as a former public health nurse who spent two decades working with New Americans, she said Dolan was an excellent choice to head the refugee office.

"She brings a depth of understanding of the journey these individuals have taken," Moffatt said. "Tracy is a very compassionate person ... She does this work because she cares about people and the community we're in."

A Standup Leader

Dolan stumbled into standup comedy in her forties, when she befriended Marianne DiMascio, a regional director at the Community College of Vermont who also writes and performs sketch comedy routines for her theater company, Stealing From Work.

"One day I said to Tracy, 'You're funny. Have you ever thought of doing comedy?'" DiMascio recalled. "And she said, 'Actually, I'd love to do standup.'"

So when Dolan first tried her hand at an open mic night at Nectar's, DiMascio was in the audience.

"She did it, and she was great — a real natural," DiMascio said.

Dolan remembers it differently.

"I'd been doing public speaking for a long time, and I got up and thought, I'm gonna be fine," Dolan said. "My legs shook the whole time."

She stuck with it and soon discovered that she had a knack for standup. When Natalie Miller and Nathan Hartswick opened the Vermont Comedy Club in November 2015, Dolan became a regular. She has occasionally taken her routine on the road, performing at the She-Devil Comedy Festival in New York City and in Boston's Women in Comedy Festival.

"You never need to worry about Tracy," Hartswick said. "She's always got her act together, [and] she always does well in front of a crowd."

Miller agreed, calling Dolan "a pillar" of Vermont's comedy scene.

"Tracy's got it all. How does she do it? She's got kids. She's got a job. And she's one of the best people in the standup scene," Miller said. "And she has experiences other people don't have ... so it's cool to hear a different perspective."

In this very different part of her life, Dolan has shown the same helping instincts that led her to public health. According to Hartswick, she helps younger comics workshop their material and hone their routines. Recently, she started shadowing Hartswick, who teaches a course on standup, and she may soon take over as its instructor.

"It's a difficult class to teach, because you have to walk the line between giving people really solid, critical feedback but also not [crush] their spirit when they're just starting out," Hartswick explained. "I think Tracy is a really good candidate for that [job]."

Gentle but Direct

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Tracy Dolan

- Afghan girls at a school Tracy Dolan and her team helped establish in Takhar Province

Soon after starting her new job, Yacouba Bogre, executive director of New American advocacy organization AALV, and Asma Ali Abunaib, who manages CVOEO's Financial Empowerment for New Americans project, requested a meeting with Dolan to talk about the needs of the arriving Afghans. Those needs will include assistance navigating the U.S. immigration system, understanding how to handle household finances in America and having ready access to translators.

"This cannot wait for someone to understand English," Abunaib said. "When you talk about financials, you talk about everything."

Dolan has also begun the flip side of her job — helping Vermonters prepare for the new immigrants. On October 19, she was among the featured guests at a Virtual Refugee Resettlement Town Hall organized by state legislators. The videoconference, with more than 100 participants and viewers, provided updates on the refugees' status and suggestions for how Vermonters could help.

Politicians spoke about the state's rich tradition of welcoming newcomers, especially those fleeing war and persecution. Others extolled Vermonters' virtues of tolerance, inclusion and hospitality.

Then Dolan offered a reality check.

"Vermont is a very welcoming state," she said, "but it is not always a welcoming state for everyone, right?"

Dolan recounted some of her experiences working with Afghan nationals and asked that if Vermonters see or hear things "playing around the edges of racism — because it can be a scary thing to think about people coming in from the outside who don't look like you — put yourselves in the shoes of others."

Dolan's message was gentle but direct, like a health department official recommending that Vermonters wear masks, wash their hands and get vaccinated.

Indeed, what got Dolan through the pandemic was the camaraderie she felt with her colleagues at the health department — "even on the hard days, that sense that you're all in it together," she said. "It's really about the desire to make the community a better place and the world a better place."

Correction, October 28, 2021: This story has been updated to reflect that Tracy Dolan and Asma Ali Abunaib have yet to meet.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Rescue Lines"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

More By This Author

Latest in Politics

Speaking of...

-

Book Review: 'The Trauma Mantras: A Memoir in Prose Poems,' Adrie Kusserow

Apr 24, 2024 -

Vermont Expat Tina Friml to Appear on 'The Tonight Show'

Nov 16, 2023 -

A Brooklyn Comedian Brings His Death-Themed Standup Act to a Winooski Funeral Home

Jun 7, 2023 -

Activist Crafter Jayna Zweiman Talks Welcome Blankets in Winooski

Feb 1, 2023 -

River Butcher Talks Jokes Versus Storytelling and Heckling Versus Cackling

Jan 18, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: