Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

News

Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down…

-

News

Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont…

-

Housing Crisis

'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted…

- Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City 0

- An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment 0

- Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Strife Lesson: Has a Cop-Turned-Educator's Assault Case Taught Him Anything?

Published February 27, 2019 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated February 28, 2019 at 5:41 p.m.

Rather than teach from a textbook, Dave Scibek looked for real-life examples to share with his criminal justice class at the Burlington Technical Center.

On November 29, 2017, he found one. He started the lesson by describing a training he'd recently attended on active shooter situations. He used it to introduce the concept of the sheepdog, a metaphor that portrays law enforcement officers as society's protectors.

Scibek, 53, identifies closely with the role. He's spent his life trying to keep people out of harm's way, as a Burlington patrol cop, a volunteer fire chief in Malletts Bay, a school resource officer and, since 2007, a teacher who prepares high schoolers for careers in law enforcement.

"The police will step in, and they will place themselves in danger and project force — extreme, violent, ugly force — to make sure people are safe," Scibek said to his students. "How far are you willing to go?"

The same question could be asked of Scibek, whose subsequent actions that day cost him his job, landed him in criminal court and could permanently change his image from man's best friend to a "wolf" who threatens the flock.

Shortly after Scibek's sheepdog lecture, 16-year-old Makayla Beverly, one of Scibek's most enthusiastic students, tossed a crumpled gum wrapper from her desk toward a garbage can on the other side of the room — and missed.

Scibek ordered her to do 20 push-ups — a long-standing, if only occasionally enforced, penalty in his unorthodox class. When she refused, Beverly said, Scibek came up behind her, dug his fingers into her neck, causing her intense pain for several seconds, then pushed her to the ground.

Scibek maintains that Beverly's defiance provided him an opportunity to introduce a police technique to his students, but he had yet to locate a pressure point behind Beverly's ear when she fell out of her chair, giggling.

Beverly said she had started having doubts about her favorite teacher when the class discussed the recent high-profile police shooting of an African American man. Beverly, who is black, questioned the white officer's conduct, and Scibek, who was known for encouraging frank debate, gave an uncharacteristically defensive response.

Beverly also said she was researching racial profiling and that her teacher had joked the day before the sheepdog lecture about profiling her.

Twelve jurors couldn't decide who to believe a year later, when the cop-turned-teacher was in Chittenden County Superior Court, defending himself against a criminal complaint that seemed unthinkable after three decades of distinguished service: assault on a child.

The jurors deadlocked, and in January, the state dismissed the charge rather than pursue a second trial. But Scibek isn't off the hook: He hasn't been allowed to return to work, and even without a guilty verdict, the Vermont Department for Children and Families and the Agency of Education could make it so that he never teaches again.

In search of a last defense, he's appealing to the court of public opinion. No other student saw the violence that he supposedly committed in plain view. Why are authorities coming after him, again, despite that fact? Don't they believe him?

Scibek suspects Vermont officials don't want to be seen as protecting a white ex-cop over a young black girl. "The elephant in the room," he said, "is maybe race was involved in this."

'On the streets'

Scibek (pronounced sea-beck) built his reputation as an approachable cop at a time of rapid change in Burlington's Old North End. He was one of hundreds who packed the Lawrence Barnes elementary school gym in the spring of 1992 with a message for the city's mayor and police chief. Residents were concerned about a trend of "inner-city" problems in the low-income neighborhood. That same week local police had carried out a drug raid, after which the brother of one of three men arrested exacted revenge by shooting and killing the 16-year-old sister of a suspected snitch.

Local media covered the crime. So did the New York Times, in a story headlined "A Taste of Urban Violence Sours A Quiet Town's Sense of Security," which noted that the men involved in the murder were black. "The ugly undercurrent of this issue is race," the Times wrote, "tactfully avoided by local reporters but often discussed on the streets."

Video of the tense meeting in the gym shows one hopeful moment: when then-police chief Kevin Scully pointed out a young Scibek, recognizable by his uniform and mustache, standing by the doors. He waved, and the crowd burst into applause.

Scibek was part of a new community-policing unit within the Burlington Police Department. At the time, it was a forward-thinking experiment aimed at reducing crime by building relationships. The foot-patrol program started with six officers, one assigned to each neighborhood. Scibek wound up in the Old North End — his first full-time job.

The Hartford, Conn., area native came to the work by way of Saint Michael's College, where he gravitated to the school's student-run fire department. Although Scibek had planned to pursue a career in business, emergency services work inspired him. By his junior year, he decided he wanted to be a cop and, in 1988, he joined the Burlington force.

Scibek excelled on North Street, an area that was transforming as hundreds of Vietnamese, Cambodian and other refugees began settling in the Old North End. In a poor, mostly white neighborhood already plagued by drug crime and family violence, the influx created challenges for law enforcement.

Scibek said he sought advice from immigrant shop owners and shared tea with the nervous mothers of Amerasian children — the sons and daughters of American GIs. He tried, unsuccessfully, to learn Vietnamese from the Mormons who offered lessons at the Sara Holbrook Community Center. But by walking the same streets every day, he was able to build rapport and trust, even with those he had to cuff, according to Bill Bissonnette, the neighborhood's largest property manager.

"Scibek had good people skills, which helped him project well with folks," Bissonnette said.

On the beat, Scibek realized that 90 percent of people are "good, honest, hardworking." That ratio, he found, did not vary by race.

"People think cops are just running around being white male racists. That was not our experience," Scibek said. "Culturally, there were just different expectations as far as how to manage conflict. We had to deal with that."

Patrick Brown, a civil rights activist who ran the Caribbean Corner restaurant on North Winooski Avenue, remembered Scibek as an "outstanding" officer who was "extremely sensitive to ethnic diversity." When Scibek's wife, current Colchester Selectboard chair Nadine Scibek, was giving birth to their second child, the officer swung by the restaurant to pick up food to bring to the hospital, Brown said.

Scibek said the years he spent patrolling the Old North End were the best of his career. The streets became safer. He'd made a mark. As one sign of appreciation, Scibek's lunch spot, the Shopping Bag, for years named its signature half-pound beef-and-bacon burger in his honor: the Scibek Sizzler.

Soon after leaving the community-policing unit, Scibek and a young Burlington cop named Shawn Burke, now the South Burlington police chief, responded to a domestic violence call that ended in bloodshed. The pair convinced a suicidal suspect to put down his gun, but the man grabbed the weapon as Burke struggled to apprehend him.

A local and state investigation into the shooting revealed that Scibek fired a split-second after the man shot and killed himself. The conclusion, the Burlington Free Press reported: The officers acted "appropriately."

Burke was a young cop at the time of the 1997 incident, while Scibek was already a family man. They continued working together once Scibek moved to detective work, but for the street cop, investigating Burlington's spiking drug-related crime felt like "a grind."

Scibek said, "My passion was the road ... Back to the road I went."

Burke said he wasn't surprised when his partner became a school resource officer at Burlington High School in the early 2000s. "The way he was able to socialize the police in the Old North End was a powerful attribute to take to a high school," Burke said.

'Good shoot'

Scibek was monitoring the high school halls when he was approached about starting a criminal justice program at the adjacent Burlington Tech. He wrote up a proposal, and the district tapped federal funds to pay his salary, plus $25,000 annually for equipment. Scibek spent his 20th and last year as a cop, from 2007 to 2008, balancing a midnight patrol shift with his new morning class. The following year, he started teaching full time — a gig that in 2017 paid Scibek $63,000 in addition to his $37,000 police pension.

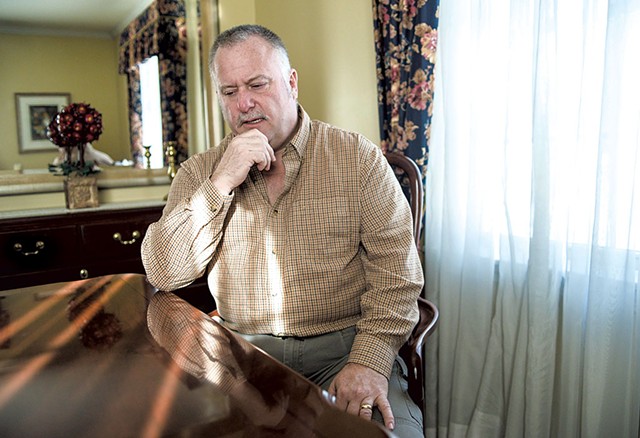

Even in the living room of his Malletts Bay home, it's easy to imagine him connecting with kids. A Catholic who isn't afraid to cuss, he speaks in an easygoing way and with a proclivity for detail that draws listeners in. He won't just tell you what toppings are on a Sizzler; he'll explain why the patties taste so fresh — the workers grind the meat seconds before throwing it on the grill — and that his adult son, Nick, worked at the Shopping Bag in high school.

The family dog, Hershey, is a beagle whose coat is turning the same salt and pepper as Scibek's buzzed hair. Sometimes he sits on the couch and licks Scibek's face. Other times, Scibek will order the dog away with a booming "Get! No, no, get!" without missing a beat in conversation.

Scibek said he wanted his program to resemble aspects of police training. With a "very supportive boss" in longtime Burlington Tech director Mark Aliquo, Scibek boasted that he was able to set it up "exactly the way I wanted."

Scibek used the program's allotted funding to purchase wrestling mats for takedown exercises, duty belts and Airsoft replica guns — Glocks for the future cops, Berettas for the military bound. He purchased a used Ford Crown Victoria at auction and had "Burlington Tech Center" painted on the side to mimic a real police department. Eventually, he converted unused space attached to the classroom into a forensics lab, complete with a fume hood and fingerprint-processing area.

The program is intensive, with 11 hours of weekly instruction stretching over two years. Juniors from nine high schools can apply. When Scibek taught, he devoted their first year of study to American policing. Students might have written a history paper one week and learned strike and block tactics the next. In the second year, Scibek taught "the art of the investigation," including forensic science.

Scibek's goal was to cultivate a classroom culture that reflected realities in the field. Students studied graphic images and contemplated gruesome scenarios; gallows humor and profanity sometimes followed. Police don't work in "safe spaces," and Scibek didn't want his classroom to be one, either. Whenever a terrorist attacked or a school shooting occurred, Scibek would flip on the television so students could watch the real-life lessons unfold. When news broke about the latest unarmed black man killed by a cop, Scibek's class would argue over whether it was a "good shoot" — industry slang for legally justified use of lethal force.

The 2014 shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., turned that into "the most riveting topic in American society," Scibek said, and he didn't shy from discussing the new critiques of policing leveled by the Black Lives Matter protest movement during class. In fact, the class had debated it during one of his last days on the job.

Scibek described his perspective on the issue over the course of five hours of interviews conducted at his Colchester home and by phone. Scibek said he would emphasize to students that Black Lives Matter's primary claim, that police departments unfairly target African Americans, is not borne out by federal crime data.

But, he told his classes, "Black Lives Matter is very accurately expressing deep-seated frustration, despair and mistrust of authority, the police being the most conspicuous element of government."

Scibek asserted that such focus on racial bias by police is misplaced because American cops shoot white people at a disproportionately higher rate than they shoot people of color.

But analyses by the Guardian and other news organizations have shown that black men are killed at a higher rate. One 2018 study by a Michigan State University researcher, however, used violent crime data to attribute the disparity to black people's more frequent involvement in criminal situations. Whether that finding disproves claims of biased policing or reinforces them is a matter of perspective.

"I can't express to you how little we care what color you are," Scibek said. "All lives matter. That's at the core of who we are as protectors."

'Twenty push-ups'

Beverly loved Scibek's course. TV procedurals such as "Law & Order" had sparked the teen's interest in forensic science. So when she saw a friend at her home school, Champlain Valley Union High, wearing an embroidered Burlington Tech criminal justice badge from Scibek's class, she decided to apply.

Beverly was a good student, and Scibek's class quickly became her favorite.

"Every day I was so excited to get up and go to criminal justice," she told Seven Days by phone. "I was in his office every single morning."

The feeling was mutual: Scibek commended Beverly in a note to CVU.

Although he didn't mention it in that communication, Scibek now claims Beverly could be a challenging student. He described her as a "drama queen," a label that derived from a joke he said the two of them shared early in the semester but which became a more serious issue later: "She made a comment: 'You're a drama queen, aren't you?' I said, 'Absolutely. There's only room for one drama queen in this program, and that's me.'

"'We'll see about that,'" he remembered her saying.

Her best friend told the Vermont State Police that Beverly "is not afraid to stand up for herself." Another student, at trial, labeled her as "snappy" and "defensive."

According to Scibek, Beverly was on a "confrontational tear" the day of the alleged assault. That "tear" included commandeering the class to plan a Secret Santa holiday party, an idea Scibek knew the district frowned upon.

Later that period, while students were quietly working on their laptops, Beverly opened a piece of chewing gum and launched the discarded wrapper across the room, as if she were trying to make a basket. That's when Scibek decided to intervene.

His first order came straight out of boot camp: 20 push-ups. One of the unique features of Scibek's class, the punishment was intended as a lighthearted way for students who messed up to quickly atone. "Your status is returned at the end of it," he explained.

But Beverly did not want to do the push-ups.

Scibek said he saw the moment as an opportunity to refocus Beverly while also using her to demonstrate a pain-compliance technique that cops use in the field. It consists of applying pressure on a bone below the ear called the mastoid process. Scibek said he yelled, "Hey everyone, watch this" before reaching for her left ear. But before he could locate the pressure point, which was obscured by her hair, Beverly collapsed. Scibek broke her fall as she slipped from the chair to the floor.

Two videos show what happened after that.

The first is a cellphone recording made by a friend of Beverly's. Scibek told the young woman not to film the incident — recordings are against class policy — but Beverly encouraged it. Just a few seconds long, the post-fall footage shows Beverly walking toward the classroom door while Scibek repeats "20 push-ups!" as he follows her, according to a Vermont State Police affidavit. Both can be heard laughing, along with other students in the class.

The second video is silent surveillance footage of the Burlington Tech hallway. It shows Scibek and Beverly talking outside the classroom. Another teacher, identified at trial as student services coordinator Joan Siegel, pulls Scibek aside for a brief conversation. Scibek walks back to Beverly and watches her do 20 push-ups. Then they return to the class, which ends a few minutes later.

When she arrived back at CVU, Beverly called her mother, Elonda, and met with the counselor and principal there. She said she cried about the incident for the first time in the CVU cafeteria.

At home, Elonda checked her daughter for injuries and found bruises on her neck and back. She took her to the emergency room at the University of Vermont Medical Center, where a physician's assistant measured a 2-by-3-centimeter bruise on the left side of Beverly's neck and additional bruising on her back.

A Burlington Police Department lieutenant interviewed Beverly at the hospital and the following day referred the matter to the Vermont State Police for further investigation because of Scibek's history with the department.

'Describe the hell'

Scibek said he finished his afternoon class thinking it had been a "normal day," until word got back to him that Beverly had claimed he had hurt her. Scibek said she had "very sheepishly" said those exact words, "You hurt me," after falling from her chair, but he interpreted her smile to indicate she was responding to his demonstration in her typically exaggerated manner.

"I was attributing it to another example of drama," he said.

The school district immediately placed Scibek on paid administrative leave pending investigation and told him not to come to work the following day. Vermont State Police Det. Sgt. Tara Thomas talked to his students at the school, and Scibek later sat for a taped interview with her and investigators from the Department for Children and Families and the school district. Thomas met with Beverly and her family but did not formally interview her.

Scibek remembers his arraignment two months later, on February 1, 2018, as the worst day of his life.

"I can't describe the hell of having to be in open court, amidst the criminal element ... and becoming an official criminal defendant," Scibek said of going before Judge Nancy Waples in Chittenden County Superior Court on a misdemeanor simple assault charge.

"I know that sounds kind of 'drama queen' of me, but it's true," he said. He faced up to one year in jail and a $1,000 fine.

The day could have been worse. Scibek did not have to pose for a mug shot, despite Thomas' request. And, given his clean record, he wasn't likely to serve time even if found guilty.

Convinced of his innocence, Scibek resolved to take the case to trial. He had good reasons to think he would prevail. Most of the students in class that day said they never saw Scibek put his hands on Beverly, and they almost uniformly described the mood as lighthearted, according to interviews summarized in the affidavit filed by Thomas.

But the state, represented by deputy state's attorney (and current Burlington City Council North District candidate) Franklin Paulino, was equally confident. Scibek had acknowledged trying to locate a pressure point near Beverly's ear, and the girl had a documented bruise on her neck.

Seven Days obtained and listened to a recording of the one-day trial, which was held last November. During it, Paulino portrayed Scibek as a former cop who had become frustrated by a student who dared to challenge his authority. Scibek's attorney, Bud Allen, described the class as a "baby police academy" that was disrupted by one student who lied to seek attention. Beverly and Scibek recounted their versions of events, as did several students from the class.

Beverly testified that she could see the anger in Scibek's face when he told her to perform push-ups in front of the class. She said he then put both hands around her throat and pressed for seven seconds. He dragged her out of her chair, and when she tried to stand up, he pushed her back down. She said her laughter in the cellphone video masked her true emotions: embarrassment and terror.

No other witnesses described Scibek as having appeared angry or said they saw him touch Beverly, aside from a witness who said he saw Scibek steadying her as she collapsed.

But none of the other students could remember Scibek telling them to "watch this," either, as he claimed.

After five hours of deliberations, the jury still could not agree on what happened, leaving Judge Martin Maley to declare a mistrial.

In January 2019, the state dismissed the charge "with prejudice," meaning the case is closed. Scibek immediately issued a blistering written statement in which he criticized the state for its "unconscionable" prosecution and the Burlington School District for not having his back.

Scibek hadn't been able to teach for 14 months. He went from paid to unpaid leave because his contract expired while the trial was pending. The class he created went on without him.

"You do not do this to honest, hardworking, law-abiding citizens," Scibek wrote.

'Old white dudes'

The dismissal of his criminal case hasn't brought Scibek any closer to the classroom. In fact, it has triggered more scrutiny.

First, he said, he received a letter from the state Department for Children and Families informing him that it had substantiated a child abuse report made against him, meaning an investigator had determined that a reasonable person would conclude the abuse occurred. Scibek has appealed, but if he is unsuccessful, his name will be added to the state's Child Protection Registry. Employers in fields that involve contact with vulnerable populations use the list to help vet potential employees or volunteers.

Scibek also received notification from the state Agency of Education that it is investigating a complaint against him. Formal charges, should the agency bring them, could cost Scibek his teaching license.

"The idea that I would be unable to work in an industry involving children, schools, emergency response, scouting — all of those things that comprise who and what I am are in jeopardy," he said.

The new threats to his teaching career have strengthened Scibek's belief that his background in law enforcement and the fact that his accuser is black have made him a target.

He described the criminal affidavit against him as a "piece of shit document" and said he finds it "inconceivable" that the Vermont State Police investigator didn't personally interview Beverly before submitting her report. The criminal charge, he said, offered an easy way for Vermont State Police to demonstrate their commitment to the antibias initiative known as "fair and impartial policing."

Scibek also points to Chittenden County State's Attorney Sarah George's Twitter profile, which states that one of her priorities is "changing old white dudes' opinions" on public safety and criminal justice reform.

"I can't help but think maybe I'm considered one of those 'old white dudes,' and ... that's a motivation for prosecuting me," Scibek said.

Vermont State Police spokesperson Adam Silverman declined to respond to questions about Scibek's case but provided a statement reiterating the agency's commitment to fair investigations, even when they involve "individuals who do not like to find themselves subject to such investigations."

George called Scibek's assertion "insulting and absurd."

Scibek isn't the only one whose life has been upended. Makayla Beverly dropped out of the criminal justice class the week after the incident because she felt isolated from her peers. She said she feared running into Scibek in public.

Elonda said the stress of taking on a well-known former cop from a prominent family weighed on the family. "I had to tell my children: Be careful, don't do anything. Don't mess up."

The Beverlys left Vermont at the end of the 2018 school year. Makayla went to live with her dad, Andrelle, in another New England state. They traveled back to Burlington for the trial and listened in horror as Scibek described Makayla as an aggressive miscreant and recounted with what seemed to them a tinge of satisfaction the moment she relented and did 20 "really good" push-ups.

"I went home and felt like, 'Was this even worth it? Do they even believe me?'" Makayla said.

Her parents wondered if their daughter's race influenced the verdict — or lack thereof.

"I just can't help but to feel like if it was a young Caucasian child, it would have went different," Andrelle said. "If I had put my hands on someone's child, I would be in jail.

"This man never spent the night in jail."

'Got it'

Paulino said he didn't think the racial questions surrounding the case warranted consideration by the jury. He saw the charge in more straightforward terms.

"To me, this case was about: Can a teacher put their hands on a student?" he said. "Should there be circumstances where that's allowed?"

Those questions were raised by Scibek's own defense, which contained an admission that he was prepared to use a police compliance technique on a disobedient student.

"This case shows that he should not be able to teach again," Paulino said. "I think it shows a complete lack of judgment."

But Scibek insists those offended by his pedagogical methods don't appreciate the program's uniqueness.

The mastoid process demonstration was a "very useful teaching strategy" that he'd employed successfully every year, and had performed countless times during his career as a cop. Scibek said he considers the inherent risks of the physical elements of his classroom no different from those of using heavy machinery in shop class.

Scibek also believed he had the tacit approval of district administrators, whom, he said, were aware of how Scibek managed his classroom for more than a decade. But the jury in the assault case did hear testimony from Siegel, the student services coordinator who came upon Scibek and Beverly in the hallway. She said she warned Scibek "no push-ups, nothing physical," or else he would have to face the school board. His response, she said, was "Got it." But Scibek acknowledged he continued to insist that Beverly comply by threatening a "family meeting" if she did not.

The district did not make superintendent Yaw Obeng or current Burlington Tech director Tracy Racicot available for an interview, and retired director Aliquo, Scibek's first boss at the high school, did not return multiple calls for comment. In a statement, district spokesperson Russ Elek said that "because the District is currently consulting with the appropriate state agencies as well as legal counsel regarding this ruling, it would be inappropriate ... to say anything else on the matter for the time being."

Seven Days attempted to compare Scibek's practices to those in the other five criminal justice programs in Vermont. Only Debra Perkins, of Stafford Technical Center, responded to questions. Perkins, a former West Virginia state trooper and Rutland police officer, said she does not teach self-defense or takedown techniques, nor does she use push-ups or other physical activity as discipline.

The Vermont Police Academy will occasionally make recruits do leg lifts as a team when one breaks a rule, director Rick Gauthier said. But he said the academy, which itself has recently faced allegations of harming recruits, abandoned instruction in the mastoid process pain-compliance technique long ago. Gauthier learned how to administer the technique in the 1980s. He described it as "extremely painful."

"I don't know how deliberately inflicting that sort of pain on somebody would help any kind of de-escalation," he said.

Vermont is one of 31 states that prohibit teachers from employing corporal punishment, which the legislature defines as "the intentional infliction of physical pain upon the body of a pupil as a disciplinary measure."

Paulino pressed Scibek at trial to acknowledge that applying pressure to the mastoid process induces pain. He then argued, in closing statements, that the reason Scibek didn't seek Beverly's consent "is because he knew that she would say no."

"Yes, isn't that a great, facile way to summarize, Mr. Paulino. Good for you," Scibek said facetiously of Paulino's argument. "But the reality is that you have a dynamic situation in your teaching, and you engage in this because the kids like it. They enjoy the spontaneity. They're not sitting down to a predictable curriculum, like most of their high school experience is. They get to explore, and by exploring, engaging in this dynamic relationship.

"And it's one based in trust," Scibek continued. "That's one thing we always talk about in my class, is that they trust that I'm going to be there for them."

'How I operate'

Was Scibek there for Beverly?

When the class discussed police shootings of black men, Beverly claimed, he was quick to defend the cops.

During those same conversations, Scibek said Beverly would "shush" students who defended the shooter, going so far as to tell them "Your opinion is not important."

When Beverly asked for Scibek's help in her research on racial profiling, she remembered that he said she didn't need help. Scibek's assessment: She wanted him to do the work for her.

When Beverly confronted Scibek for admonishing her for being careless with her laptop, but not another girl who was spinning hers in the air, Scibek asked if she thought he was racially profiling her.

Beverly said she hadn't considered the possibility until that moment. She's thought a lot about it since.

"I definitely feel like the situation was racially motivated," Beverly said of their subsequent physical encounter.

Scibek is still struggling to understand why.

"Where the hell did she come up with the fact that she was somehow being singled out and treated differently?" Scibek asked. "The concept of me being motivated by racial tendencies or perceptions or opinions is ludicrous. It is not how I operate."

Yet it is how most school systems operate. Black and brown students are disciplined in schools at higher rates than white kids. Vermont is no exception. A published analysis of school data by Vermont Legal Aid found that black students in Chittenden County were three times as likely to receive an in-school suspension as their Caucasian peers and twice as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension. The disparity has prompted some parents to demand change in Burlington schools.

The Beverlys said Vermont school officials haven't contacted them to apologize or to inquire about Makayla, who is still pursuing a career in forensic science or detective work as an honor-roll senior. "I just want to help people out there who have a similar story to mine get their story out, so that it doesn't happen to anybody else," she said.

Her parents declined to provide a photo of their daughter for this story and asked Seven Days not to reveal her new state of residence. They said Scibek's arrogant self-assuredness about his actions indicate that he should never be in charge of students again.

"It's the same behavior we're seeing every day on television with police officers," Andrelle said. "They make a mistake and think nothing is going to happen because I am a police officer. I serve my community; I can get away with anything I want now."

There's a good chance Scibek won't get another chance to teach. At this point, teaching may not be what Scibek cares about most.

"Tell me I'm not a protector," he said.

Scibek was addressing the State of Vermont. But he seemed to be daring anyone to try.

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

More By This Author

About The Author

Derek Brouwer

Bio:

Derek Brouwer is a news reporter at Seven Days, focusing on law enforcement and courts. He previously worked at the Missoula Independent, a Montana alt-weekly.

Derek Brouwer is a news reporter at Seven Days, focusing on law enforcement and courts. He previously worked at the Missoula Independent, a Montana alt-weekly.

Speaking of...

-

Lawsuit Accuses Burlington Police of Using Excessive Force on Black Teen With Disabilities

Jan 31, 2024 -

Burlington Council Moves to Declare the Drug Crisis a Top Priority

Sep 7, 2023 -

The Acting Chief: For Three Years, Jon Murad Has Auditioned to Be Burlington's Top Cop. Will He Finally Get the Role?

May 3, 2023 -

National Law Enforcement Experts Come to Burlington to Share Ideas on Police Reform

Feb 20, 2023 -

Northfield’s Police Chief Takes Flak for His Provocative Public Stances

Feb 15, 2023 - More »

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. 'We're Leaving': Winooski's Bargain Real Estate Attracted a Diverse Group of Residents for Years. Now They're Being Squeezed Out. Housing Crisis

- 2. Through Arts Such as Weaving, Older Vermonters Reflect on Their Lives and Losses This Old State

- 3. Aggressive Behavior, Increased Drug Use at Burlington's Downtown Library Prompt Calls for Help City

- 4. Middlebury College President Patton to Step Down in December News

- 5. Overdose-Prevention Site Bill Advances in the Vermont Senate News

- 6. High School Snowboarder's Nonprofit Pitch Wins Her Free Tuition at UVM True 802

- 7. An Act 250 Bill Would Fast-Track Approval of Downtown Housing While Protecting Natural Areas Environment

- 1. Totally Transfixed: A Rare Eclipse on a Bluebird Day Dazzled Crowds in Northern Vermont 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 2. Zoie Saunders, Gov. Scott’s Pick for Education Secretary, Faces Questions About Her Qualifications Education

- 3. Don't Trash Those Solar Eclipse Glasses! Groups Collect Them to Be Reused 2024 Solar Eclipse

- 4. State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News

- 5. Vermont Awarded $62 Million in Federal Solar Incentives News

- 6. New Jersey Earthquake Is Felt in Vermont News

- 7. Barre to Sell Two Parking Lots for $1 to Housing Developer Housing Crisis