Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

UVM Scientists Unearth Bad News for Our Climate Future Beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet

Published October 11, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated October 18, 2023 at 10:08 a.m.

click to enlarge

- Luke Awtry

- From left: Paul Bierman, Halley Mastro, Cat Collins and Juliana Guimaraes Ribeiro de Souza

Halley Mastro slid a petri dish of liquid speckled with floating debris under a microscope. After adjusting the focus, she let a journalist visiting her University of Vermont geology lab take a peek. Even a nonscientist could recognize the magnified specks as pieces of plants.

"That spiky thing and that black thing next to it are moss stems," said Mastro, 22, a master's student from New Paltz, N.Y., who is studying the ancient ecology of northwestern Greenland. "It just looks a little funky because it's been frozen for 400,000 years."

Beside her sat fellow master's student Catherine "Cat" Collins, who pulled up a rainbow-colored picture on her laptop screen. Dotted with reds, yellows, greens and blues, the blob resembled a Doppler radar image of a severe thunderstorm. In fact, Collins, 24, used a CT scanner to capture this snapshot of frozen sediment from beneath a Greenland glacier — part of the same sample that contained Mastro's ancient mosses. Collins uses CT and other computer imagery to study how those sediment layers formed in the distant past. The data helps scientists understand how long the Greenland ice sheet has been there — and how warm the climate was when the ice last melted.

The two scientists and a third colleague, Brazilian geologist Juliana Souza, 25, are working with glacial sediment extracted by the U.S. military during the Cold War, long before any of them were born. And they calculate that material's age with the help of cosmic rays that emanated from beyond the solar system eons ago.

The science happening in this dust-free clean room on UVM's Trinity campus may seem esoteric, but it has a very practical and urgent application: to understand the effect of human-induced climate warming on the Greenland ice sheet, which is a growing source of meltwater that contributes to rising sea levels around the globe.

"This is science that matters," said Paul Bierman, an environmental science professor in UVM's Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, who oversees the $1 million laboratory.

In July, Bierman and an international team of fellow scientists published a study in the journal Science that attracted worldwide media attention. Their research had determined that northern Greenland was ice-free as recently as 418,000 years ago, at a time when the Earth's climate was in a warming period. That finding, based on frozen soil samples the U.S. military drilled from deep below a glacier in 1966, upended scientists' previous assumption that the Greenland ice sheet has been stable for millions of years.

Scientists already knew that sea levels were 20 to 40 feet higher 418,000 years ago. But Bierman and his team were the first to show that as much as 20 feet of that sea level rise came from the Greenland ice sheet — which could disappear again by the end of this century. That's a cataclysmic scenario, given that 40 percent of the world's population — more than 3 billion people — live near a seacoast.

"Think about going to Massachusetts with the sea level 20 to 40 feet higher than it is today," Bierman said. "Boston becomes a series of islands."

The Science paper made a huge splash, in part because it appeared during the hottest week ever recorded on Earth. But the discovery also has an intriguing, little-known backstory: a bizarre Cold War scheme featuring a subsurface lair that seems plucked from a James Bond movie; a decades-old transcontinental mystery; and a stroke of dumb luck. Bierman has documented it all in his upcoming book, When the Ice Is Gone: Greenland's Warning to the World, due out in August 2024.

During his 40-year career, Bierman, 61, has analyzed tectonic faults in California's Owens Valley, land erosion in Australia and Africa, and the impacts of organic farming on water quality in Cuba. Closer to home, he and his undergraduate students have studied landscape change in rural Vermont, landslides on Burlington's Riverside Avenue and the loss of green space in student neighborhoods. But Bierman described the revelation that Greenland was once ice-free as his only eureka moment. And it might never have occurred were it not for the 10 years he spent studying how glaciers reshaped the landscape of the Green Mountains.

When Bierman first spotted those tiny floating specks of organic debris — the kind visible under Mastro's microscope — he knew he had seen something similar before, in sediment drawn from Vermont's ponds and lakes. That realization flipped the script on the Greenland ice sheet — and scientists' understanding of our planet's past and future.

A City Buried in the Ice

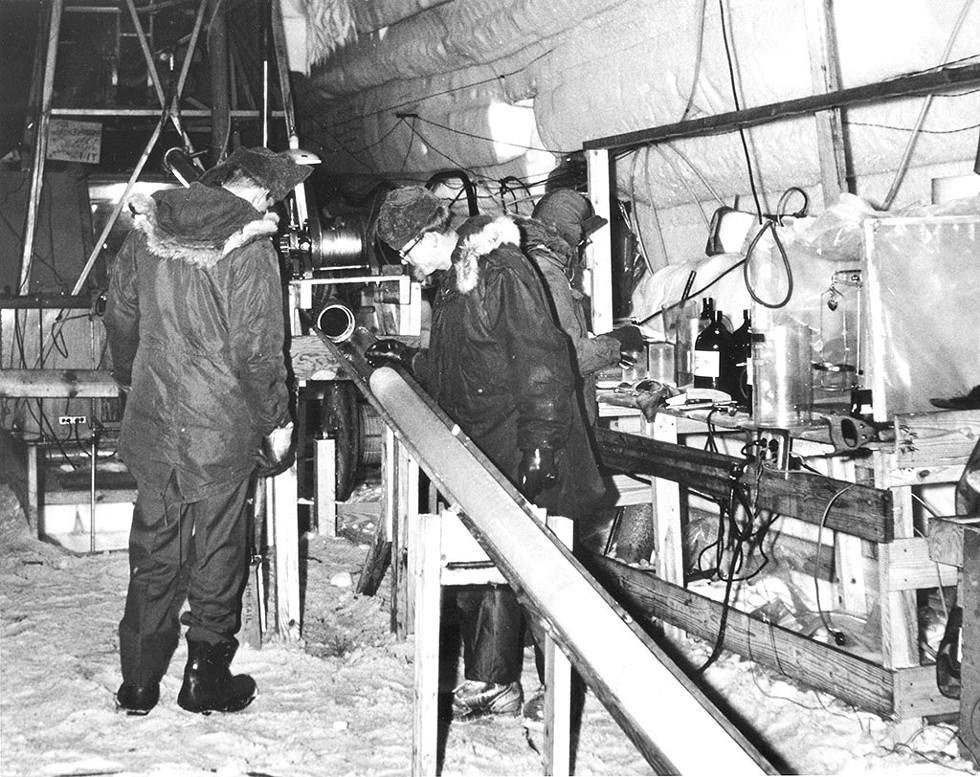

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Aip Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

- J. Kasl and D. Garfield viewing a retrieved core at Camp Century in 1966

Bierman is a veteran teacher whom students describe as easygoing, whip-smart and extremely supportive. His internationally renowned laboratory, funded by nearly $3 million in grants from the National Science Foundation, attracts dozens of visiting researchers from around the world every year.

And plenty of reporters. Bierman and Drew Christ, a former UVM geologist with whom Bierman collaborated on the Science paper, were interviewed over the summer by the New York Times, Washington Post, CNN, BBC, London's Times and Le Monde, to name a few. Just days after we met, Bierman spoke to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy about his Greenland discovery. His message to Washington, D.C.: If we don't rapidly decarbonize the economy and reduce atmospheric CO2 levels, much of Greenland's ice will melt into the sea.

Amiable and chatty, Bierman speaks in plain English, is generous with his time and dresses as casually as an undergrad. On the morning we met, he arrived at the lab in shorts, Crocs, a T-shirt and a baseball cap.

Bierman is also a compelling storyteller with a fascinating tale about the source of the sediment that revealed Greenland's ice-free past. The story begins in the 1950s, at the height of the Cold War, when the U.S. military concocted a scheme to hide nuclear missiles beneath the ice about 120 miles inland from the northwest coast of Greenland. The location would have put the warheads hundreds of miles closer to the Soviet Union than those on the continental U.S.

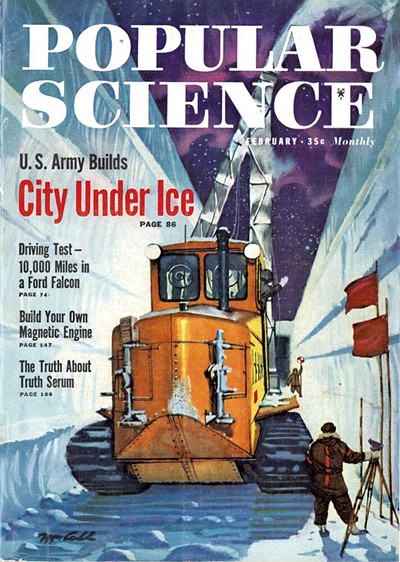

The plan, called Project Iceworm, was ostensibly top secret, though an article published in Popular Science in the early 1960s disclosed the military's intention to build a "subway under the ice" that would shuttle as many as 600 ballistic missiles through a network of tunnels, making them less vulnerable to a Soviet first strike.

In 1959, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began building a military base, Camp Century, buried 150 feet below the surface of the Greenland ice cap. The base had chemistry labs, hot showers, a chapel, a movie theater and as many as 200 inhabitants who lived there year-round. The nuclear missiles were never deployed, but the entire base was powered by a portable nuclear reactor.

Part of the Army's interest in Camp Century, in addition to hiding nuclear missiles, was to study the feasibility of living and traveling in extreme environments in the event of conflict with the Soviet Union in the far north. By the 1950s, the military had documented the retreat of arctic sea ice. If the ice were to melt, the military needed to know how that would affect its ability to defend against a Soviet attack over the arctic circle.

As a cover story for Camp Century, the military brought in civilian glacier scientists who drilled nearly a mile through the ice sheet — and, critically, another 12 feet into the frozen sediment below it — and extracted core samples to study.

That research, led by glacier scientist Chester Langway, was a sideshow to Camp Century's defense mission. But as Bierman pointed out, "The people doing it were smart enough to say, 'The military is paying to get us up here. Let's do some cool stuff.'"

Drilling into the mile-thick glacier began in 1961, initially with a device meant to melt through the ice. That plan failed, Bierman said: The drillers made it only a third of the way to the bottom. Later, they brought in an electromechanical drill from an oil field, adapted for ice drilling, which completed the task with industrial efficiency. In one year, they drilled the remaining two-thirds' distance to the bottom of the glacier and, crucially for Bierman, another 3.5 meters into the frozen soil below it. Legend has it that the final core sample was extracted on July 4, 1966.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Halley Mastro

- A scientist removing an ice core from its storage tub and placing it on a light table to study layering

"It was 100,000 years of climate history coming out of the ice, which was great," Bierman said. "But the sediment at the bottom? Nobody knew what to do with it."

Meanwhile, the military realized that Project Iceworm was doomed. Ice is a dynamic environment, and the tunnels quickly deformed and compressed, making it impossible to bury permanent structures. Camp Century was abandoned in 1967.

When the Greenland project ended, the core samples were sent to the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, in Hanover, N.H., where they were stored until 1974. Langway, Camp Century's chief glacier scientist who coordinated the ice core analysis in Hanover, moved the entire collection to the State University of New York at Buffalo, where he chaired the geology department.

But after Langway's ouster as chair in the early 1990s, the National Science Foundation wanted the collection moved to Colorado, effectively ending his control of it. As an act of defiance, he withheld the deepest core samples, which he offered to longtime colleagues in Denmark. If they weren't interested, Bierman said, Langway planned to toss them into Lake Erie.

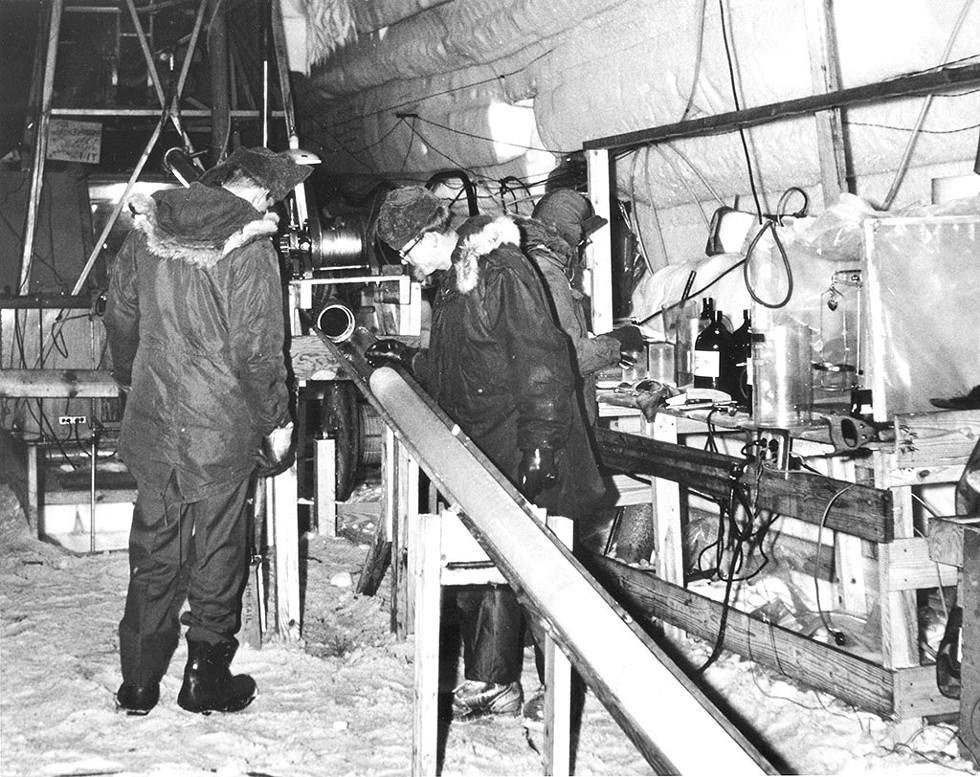

click to enlarge

- Courtesy of David Atwood/AIP Emilio Segré Visual Archives

- View of the drilling setup in Trench 12 at Camp Century in 1961

Fortunately, the Danes did want them. Langway shipped the sediment samples to Copenhagen without anyone's knowledge. Years later, ice core scientists lamented their disappearance, noting that such a mammoth and costly drilling project probably would never be replicated.

Bierman was studying glaciers in graduate school in the late 1980s and early '90s when he first heard stories about the 200 men who once lived embedded in the ice of Greenland. He didn't pay those tales much attention until 2010, when he and Thomas Neumann, a UVM colleague, got hold of some of the original samples from Colorado.

"And then I started thinking about what was at the bottom," Bierman said. Though dozens of papers had been published on the ice samples, only three, from decades earlier, addressed the frozen soil below it.

Bierman was 4 years old when that last core sample was extracted from the bottom of the world's second-largest glacier. He learned its fate in 2018, when he encountered Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, a Danish paleoclimatologist known for her work on ice core samples, at a meeting in Buffalo.

"She said, 'Paul, you should come to Denmark. We just found a bunch of old ice,'" he said.

Housed in a Danish freezer were 28 sealed and long-forgotten glass cookie jars. Inside, were Camp Century's lost core samples.

Hands in the Cookie Jar

"There are a few moments in all of our lives where your spine tingles," Bierman recalled about the day in April 2019 when he stood inside a Danish freezer nearly the size of a soccer field. "When I held that jar, I was like, This is the bottom of Camp Century. We all thought it was long gone."

Researchers have long suspected that the material at the bottom of glaciers can be some of the most revealing. Though ice can tell part of the region's history, geologists generally need a much longer time scale to peer into the distant past.

The frozen sediment from the bottom of the Camp Century borehole gave Bierman and his colleagues that once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. He and others describe the sediment samples as "rarer than moon rocks."

That's not hyperbole. Between 1969 and 1972, six Apollo space missions returned to Earth with 842 pounds of moon rocks. The Camp Century mission brought up frozen sediment weighing 69 pounds. "And we haven't done that since," Bierman said.

Because Bierman's UVM lab is considered among the best in the world for analyzing such materials, the Danes gave him a sample of the frozen sediment about the size of his fist.

On a hot summer day in July 2019, Bierman and Christ went into the lab and melted some of it. Though any concerns they might have had about exposure to prehistoric toxins or microorganisms proved unfounded, when they first opened the cooler, "Drew and I got knocked over by the smell." The strong odor came from the mixture of diesel and trichloroethylene used in the Camp Century drilling. The scientists quickly moved all of their work under a fume hood.

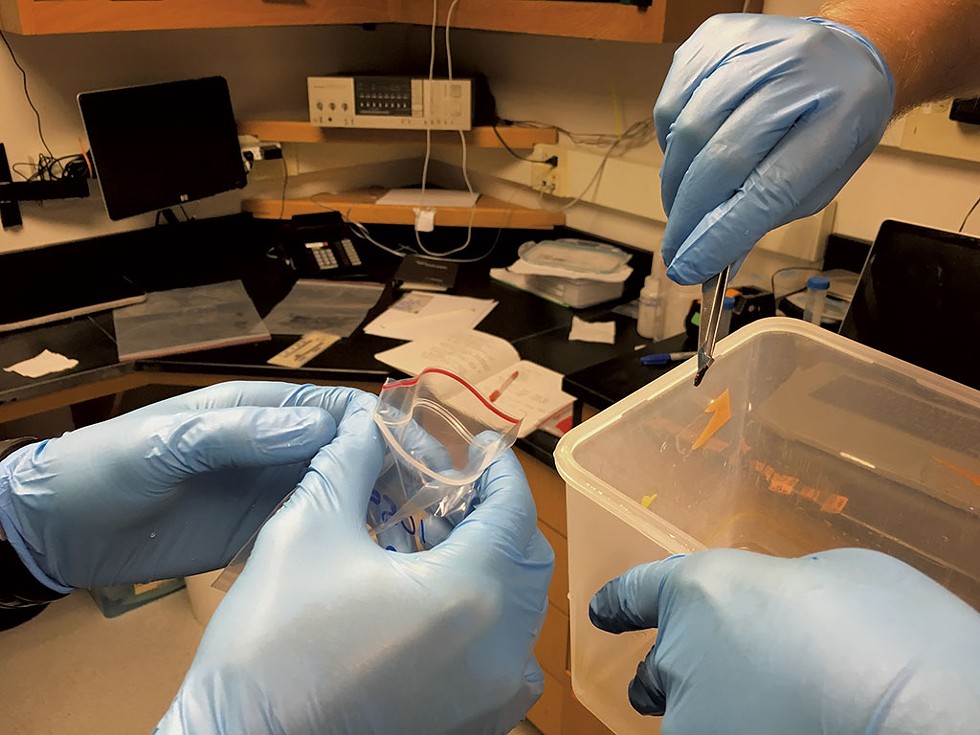

Because the sample was irreplaceable, Bierman and Christ ran it through a series of brass sieves to preserve every speck of material. What they found could easily have been overlooked.

"I'd been teaching high school students all week and was completely zoned out and was just staring at this bucket of wash water," Bierman recalled. "And then I see these little floaties in it."

Those floating specks immediately triggered Bierman's memory of his research on Vermont lake beds.

"I went to Drew and said, 'Drew, there are fossils in here,'" Bierman recalled. "He looked at me like, You are totally crazy."

Using tweezers and a pipette, Bierman plucked out the debris, dropped it in a petri dish and told Christ to put it under a microscope.

"It took about 10 seconds before he raised his head up with a string of happy profanities," Bierman said. "We'd found this ecosystem that had been frozen for who knows how long."

Long ago, on a site in northwestern Greenland now covered by a mile-thick sheet of ice twice the size of Texas, plants once grew.

But how long ago?

A Cosmic Discovery

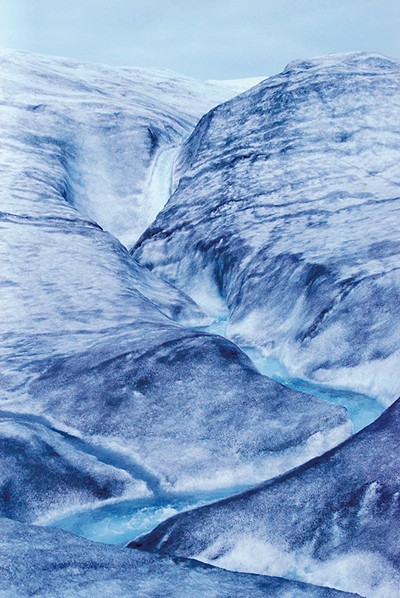

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Paul Bierman

- The Russell Glacier ice margin near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, with bedock, till and tundra beside meltwater streams

Just down the hall from the clean room in UVM's Delehanty Hall, grad student Souza walked me through the mineral separation lab.

Souza is a glacier researcher who studies the geochemistry of polar environments. As one of Bierman's three grad students on the Camp Century project, she spent two months this summer on Alaska's Juneau Icefield studying glaciology alongside National Aeronautics and Space Administration personnel prepping for an upcoming space mission.

But it's in the mineral separation lab where, as she put it, "most of the dangerous stuff happens."

She uses hydrofluoric and nitric acid to reduce Camp Century sediment samples down to pure quartz. The ultrafine white powder she produces resembles the sand in an hourglass. She sends it for analysis to repurposed, 1960s-era particle accelerators elsewhere in the country. There, computers count the individual atoms of radioactive isotopes. This painstaking process enables researchers to pinpoint the age of the sample, which is too old to carbon-date.

This technique, which was crucial to the Science paper published in July, didn't exist at the time of Camp Century. In fact, Bierman was still a grad student studying how glaciers eroded the landscape when an adviser suggested that he shift his academic focus to a relatively new field of research: cosmogenic isotopes, which are mildly radioactive elements formed by high-energy cosmic rays emanating from beyond our solar system. Bierman now focuses on two — beryllium-10 and aluminum-26 — that are so rare, he likened them to finding a single drop of water in an ocean.

When minerals sit on the Earth's surface, Bierman explained, cosmic rays strike the nuclei of their oxygen and silicon atoms, creating beryllium-10 and aluminum-26, respectively. But once that material is buried, he explained, far fewer cosmic rays reach those atoms and "the clock starts ticking."

Because the isotopes decay at different rates, scientists can use the half-life differential to calculate how long the material has been buried. Tammy Rittenour, a geologist who runs a luminescence dating lab at Utah State University and who coauthored the Science paper with Bierman, used this technique to pinpoint the age of the Camp Century sediment at 418,000 years old.

Why does its age matter?

As Bierman explained, we now know that 418,000 years ago the Greenland ice sheet vanished during a period when the Earth was as warm as it is today. But unlike today's climate, that warming period was caused by a natural wobble in the Earth's solar orbit — and the change in climate took 20,000 years. By comparison, much of the current warming in the Earth's average temperature began at the start of the Industrial Age, just two centuries ago.

"The scary part for me is that we're setting up our climate to be warm for the next 10,000 to 20,000 years," Bierman added. "This is not a normal cycle, and the rate at which we're doing it is astronomically faster than when nature does it. We're going into uncharted territory."

What's Next

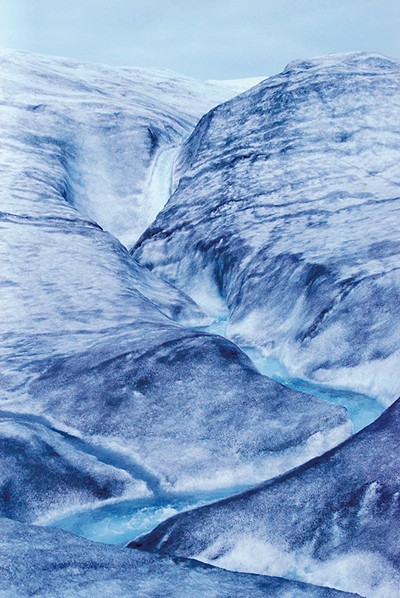

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Paul Bierman

- Meltwater pouring over ice at the edge of the Greenland ice sheet

The research published earlier this year on the Camp Century core samples was groundbreaking in its implications. But the core samples have more stories to tell. Thus far, Bierman and his team have published papers on just two of the existing samples, what he called "the low-hanging fruit."

More than two dozen remaining samples span a period of 1.5 million to 3 million years, dating to the Pleistocene epoch, aka the Ice Age. His students have been analyzing the ancient material for the past year. The data they produce will be invaluable in helping climate scientists understand how the world's ice sheets work, how long they have lasted and how they respond to dramatic changes in the climate.

"The question on this is: How much of Greenland's ice will survive, and for how long?" he said. "If we don't understand these ice sheets, we can't do a very good job of planning for the next 100 years.

"It's no longer just a scientific problem," Bierman said. "It's a survival problem for upwards of a billion people who, if Greenland and Antarctica melt, are going to lose their place to live."

Bierman knows he won't be the one answering all of those questions. So he's preparing the next generation of scientists to carry on this research.

"It's a very broad lab, and it's pretty incredible all the output that has come out of it since Paul's been there," said Christ, the former UVM researcher who's since moved to Colorado to pursue a career outside of academia. Christ described Bierman as having "a boundless enthusiasm for science" and the students he teaches.

It's no coincidence that all three grad students recruited for the Camp Century project are women in their twenties. As Bierman noted, the National Science Foundation, which funds his research, is eager to change the face of polar science, which for decades has been dominated by white men.

There's another reason Bierman recruited young scientists to his team: They're part of the generation that will need to confront the realities of rising sea levels. As he put it, "It's emotional to think about a mile of ice melting away."

While there's no scientific consensus yet on how warm the planet can get before the Greenland ice sheet melts, he said, "once it falls apart, we're not getting it back anytime soon."

Today, there's nothing left to see at the surface of Camp Century. But encased beneath the ice are more than 200 million tons of debris. When the base was decommissioned in 1967, Army engineers assumed that the waste would be locked up forever by cold and perpetual snowfall. But as global temperatures have heated up, a study done in 2016 predicted that the wreckage could emerge from the ice within 75 years.

"It's only a matter of time before this camp begins to surface," Bierman said, "and all that shit is going to [see] daylight."

Bierman meant it literally. In addition to tons of low-level nuclear waste, PCBs, asbestos and lead, the 200 military personnel stationed at Camp Century left behind six years of human waste.

As a metaphor for our climate future, it doesn't get more spot-on than that.

The original print version of this article was headlined "On Thin Ice | UVM scientists unearth bad news for our climate future beneath the Greenland ice sheet"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Ken Picard

Bio:

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

Ken Picard has been a Seven Days staff writer since 2002. He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Vermont Press Association's 2005 Mavis Doyle award, a general excellence prize for reporters.

More By This Author

Latest in Environment

Speaking of...

-

Video: Plainfield Recovers From Catastrophic Flood

Jul 25, 2024 -

Garimella Supported UVM Commencement Speaker Just Days Before Cancellation

Jun 4, 2024 -

Youth Conservation Crews Head Out to Repair Damage From 2023 Floods

May 22, 2024 -

Growing Pains: How Warmer, Wetter, Wilder Weather Is Compelling Vermont Farmers to Adapt

May 15, 2024 -

Pro-Palestinian Encampment at UVM Has Disbanded After 10 Days

May 8, 2024 - More »

find, follow, fan us: