Published November 4, 2009 at 8:09 a.m. | Updated November 7, 2017 at 12:34 p.m.

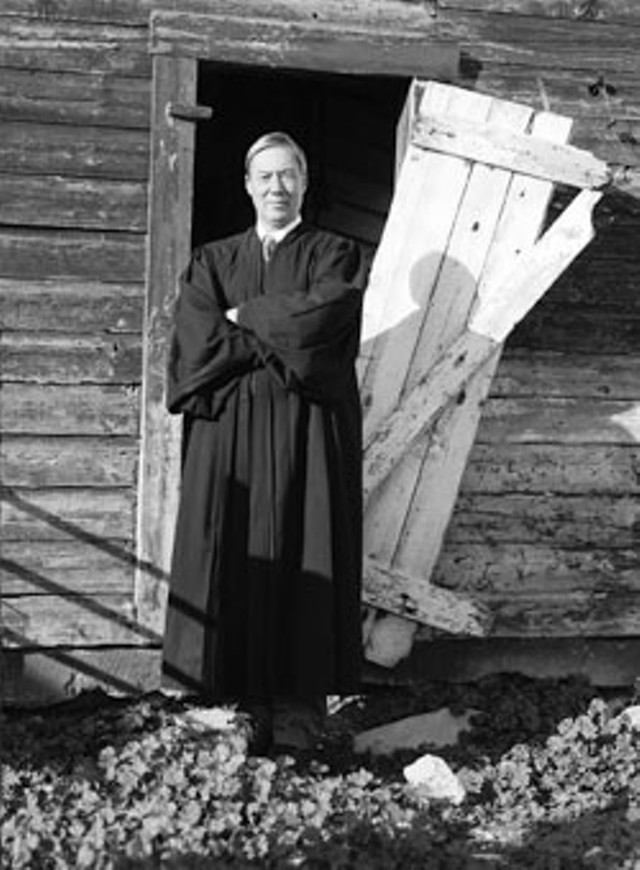

The Vermont judge who ruled in favor of the Sierra Club. in a landmark auto emissions case is going to head up the United States Sentencing Commission. President Barack Obama nominated William K. Sessions III, 62, for the plum judiciary job in April. After a delay — thought to be payback for Obama’s nomination of Sonia Sotomayor — the full U.S. Senate finally confirmed Sessions at the end of October.

A Middlebury grad, Sessions went to law school in D.C. but returned to Vermont in 1973 to clerk for Judge Hilton Dier in Addison County District Court. He worked as a public defender, in private practice and as an adjunct professor at Vermont Law School before President Clinton appointed him to serve as judge on the U.S. District Court in Burlington in 1995. Since 2002, he’s been chief judge in the court where Vermont’s federal cases are tried.

Sessions has issued a number of controversial rulings from his bench above the Burlington post office. In the United States v. Donald Fell — a murder in which the perpetrator brought a Vermont woman across state lines to kill her — he found the death penalty unconstitutional because of sentencing procedures. In 2007, he allowed Vermont to adopt fuel-economy standards set by the State of California in a challenge to federal preemption law.

Sessions has served as vice chair of the U.S. Sentencing Commission since 1999, but as chairman he will have considerable power over the body’s agenda. That means Sessions will be instrumental in deciding what constitutes a crime and how long an offender goes to jail for committing one. It extends way beyond medical marijuana. Seven Days caught up with Sessions at Middlebury College, where he was giving a presentation on federal preemption and environmental law.

Seven Days: Why did Congress create the United States Sentencing Commission in 1984?

William Sessions: The commission was the product of negotiations between liberals and conservatives to reduce or eliminate the disparity in sentencing [for federal crimes]. A number of studies had indicated if you were being sentenced in Alabama, for instance, you were receiving a totally different sentence than if you were sentenced in New York. More than that, people would say that the sentence you received in a multi-judge district would depend on the luck of the draw. Some judges would impose probationary sentences while other judges would impose very significant prison sentences. Senators Kennedy and Thurmond were basically the authors of the act.

SD: You were appointed to the commission by President Clinton in 1999, served as vice chair during the Bush years and were elevated to chair by President Obama. Does the USSC have a discernible political bias, and have you seen it change over time?

WS: It doesn’t have a political bias. In fact, it’s one of the few significant organizations that works in a totally nonpartisan way. There are seven commissioners: three from one party, three from the other party and the chair to be selected by the president. As long as I’ve been on the commission, we have tried to work by consensus, and that’s been extraordinarily successful. For 10 years, we’ve dealt with a lot of controversial issues. Eventually, we come close to consensus on virtually everything.

SD: How do changes in the sentencing guidelines come about?

WS: We propose a list of guideline changes prior to May 1st of each year. We send Congress a list of changes to the guidelines. Congress has six months to reject those proposals; if they don’t reject them, they become law. It has happened only two times in history that Congress has rejected our proposals.

SD: What are the commission’s strengths?

WS: One generally thinks of sentencing as being the responsibility of the judge. That’s not true. All three branches of government have an interest in sentencing policy. Congress has an interest because it determines the penalties that are attributable to crimes, and the president, through the Department of Justice, has an interest in what penalties are imposed. The sentencing commission meets at the junction of those three branches of government, and we try to reflect in the guideline system the interests and input of all three branches.

Second, we have a whole set of factors that judges should consider before imposing sentence. When you make a decision about somebody’s human liberty, there are a lot of things you have to think about. In some ways, the guidelines reflect the norms of the public — this is what the public expects in regard to these particular offenses, with, of course, exceptions based on the individual characteristics of the defendant.

The other advantage is that it reduces disparity. We have a system that sets ranges of penalties that are applied nationwide. If you are going into court in Arizona, you are being sentenced the same as someone going into court in Indiana.

SD: Originally, the sentencing commission established mandatory minimum sentences and mandatory guidelines for sentencing. The mandatory guidelines were found unconstitutional in 2005, but the minimums still exist. Do they create a problem for judges?

WS: Guidelines are now advisory, but Congress has the power to impose mandatory minimum sentences. Congress says that if you are charged with crack cocaine and your offense involved 5 or more grams, then your mandatory minimum sentence must be at least five years. The corresponding mandatory minimum five years for powder cocaine is 500 grams. That’s where the 100:1 ratio comes into play. That’s what Congress is dealing with at this point, trying to reduce or eliminate the disparity between crack and powder.

Judges do not have the power to impose a sentence below those minimums. There may be circumstances in which a judge will want to impose a sentence below the mandatory minimum. The sentencing commission has, in the past, written reports opposing mandatory-minimum sentences. The latest report was 1991. Congress has just passed a law, which will be asking the sentencing commission to write a full report on mandatory minimum sentences that must be submitted within one year.

SD: What are the greatest challenges facing the commission at the moment?

WS: The difficulty is always in balancing the input of the various branches of government. That’s a continuing concern and responsibility that we have.

If you’re talking about specific issues facing the commission, probably the crack versus powder disparity is one of big concern. The commission proposed to Congress a few years ago that the 100:1 ratio be addressed and that the ratio should be no greater than 20:1 and that there should be no increase in penalties for powder cocaine. That has not been accomplished to date.

But two years ago, the commission, on its own, chose to reduce penalties for crack cocaine by two levels on the [sentencing guideline] table. That translates to, on average, two years. And then we decided to apply those reduced penalties retroactively. We went back into the prisons … people who had been sentenced pursuant to the guidelines were eligible to be re-sentenced with the much-reduced penalty. As many as 18,000 to 20,000 people have had their sentences reduced.

SD: Your commission will meet next week to prioritize issues for the upcoming year. What issues are likely to be on the agenda?

WS: For instance, crack cocaine and powder cocaine is a possible issue. There’s a career-offender guideline — it’s a heightened penalty if you’re convicted of a number of previous drug or violent offenses. There’s a guideline on armed career criminals that needs review. There are a growing number of cases dealing with immigration and illegal reentry into the country — people who are deported and come back are subject to criminal penalties. People complain about the severity of the drug penalties all across the board. These are the kinds of issues we’re likely to take up.

SD: Is the commission responsive to changing social values and mores?

I think the commission tries to be responsive to law-enforcement concerns in particular. Let’s say all of a sudden a new drug is introduced into a community. We clearly need to respond to that by establishing a guideline structure. If society, through its representatives in Congress, thinks that there is a particular emergency, they try to pass laws to increase penalties for those offenses, and we try to be responsive to direction from Congress.

One example is Ecstasy. We did this massive study of the chemical qualities, the dangers of the drug, its impact on local communities, and then made a decision as to what would be the appropriate penalties.

SD: We’ve talked about drugs. What about other types of crimes?

WS: You have bank-robbery convictions. There’s fraud. We increased the penalties for white-collar offenses very dramatically since I’ve been on the commission. They were fairly low. Prior to Enron, the commission had done a whole series of studies and increased the penalties for those white-collar offenses. And then Enron happened and Congress responded with much more increased penalties and urged us to increase penalties more, which we did. To that extent, we found ourselves responsive to Congress and public concern.

So then there’s a lot of immigration. We have implemented a number of guidelines to dramatically increase the penalties for terrorism. There are issues in regard to child pornography and child exploitation — they’re very dangerous crimes, and we have very stiff penalties for those offenses. The other major area is firearms — felons in possession of firearms or use of firearms in connection with drug transactions.

More By This Author

Speaking of...

-

Best rock artist or group

Aug 1, 2018 -

Former Burlington Cop Charged With Lying About Drug Bust

Aug 30, 2017 -

Vermont Muralists Tackle More Blank Walls

Aug 2, 2017 -

Is the Vermont DMV up to the Job?

Jul 26, 2017 -

Cop on the Tweet: Chief's Social Media Posts Draw Criticism

Jul 5, 2017 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.